The known: In Australia, infants are not routinely screened for congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections. The burden of disease associated with such infections is consequently unknown.

The new: The number of congenital CMV infections recorded by the longest running CMV infection surveillance study in the world is only about 1% of the number expected based on published estimates of their prevalence. Guthrie cards can be used to retrospectively diagnose congenital CMV infections, facilitating better case ascertainment.

The implications: Universal newborn screening for CMV infections could improve their timely detection and prompt treatment that could avert neurological and other adverse consequences.

The birth prevalence of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection ranges from 0.2% to 2.0% in developed countries,1 and from 0.6% to 6.1% in developing countries;2 10–15% of fetal CMV infections are symptomatic,3 and 0.5% are fatal.4 Clinical sequelae of congenital CMV infection include microcephaly, cerebral palsy, mental disability, sensorineural hearing loss, intracranial calcification, and visual impairment;5,6 clinical sequelae also develop after 10–15% of asymptomatic congenital CMV infections.3,7 Although CMV is one of the major infectious causes of fetal neurological malformation, awareness of the risk is limited among both medical professionals and parents.1,8,9

The mortality and morbidity associated with congenital CMV infection are influenced by several factors: medical professionals and parents are not aware of the infection; testing and screening of mothers and infants are not routinely undertaken; the efficacy of antiviral therapy is limited and its toxicity high; and a licensed, effective CMV vaccine is not available.10 The efficacy of an MF59‐adjuvanted gB subunit (gB/MF59) vaccine in phase 2 clinical trials was about 50%,11,12 and clinical trials of mRNA‐based and other vaccines are underway.13 Symptomatic CMV infections in infants should be identified as soon as possible, as antivirals administered during the first four weeks of life modestly improve neurodevelopmental outcomes for severely affected infants.14,15

In Australia, universal screening for congenital CMV infection is not undertaken, resulting in limited detection of infants at risk and underestimation of the burden of disease.3,16,17,18 We therefore investigated the birth prevalence, clinical manifestations, and management of congenital CMV infections during 1999–2023 by analysing Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit (APSU) surveillance data, the longest running CMV study in the world.3,18,19

Methods

The data for our observational study were prospectively collected according to the published APSU surveillance method and CMV study protocol, as described in previous articles.3,16,18,19 The study was part of the APSU network of studies, affiliated with the Paediatrics and Child Health Division of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians, the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences of the University of Sydney, and the Sydney Children’s Hospital Network. The original APSU study commenced in Sydney on 1 January 1999. We report our study according to the STROBE statement for reporting cohort studies.20

Prospective surveillance of congenital CMV infections in Australia by the APSU commenced on 1 January 1999. Briefly, each month a mean 1300 paediatricians and other child health specialists working in urban and regional areas in every state and territory who are registered with the APSU receive a list of up to fifteen rare conditions, including CMV infection, and are asked whether they have seen children with any of these conditions during the preceding month. If they have, the contributor is asked to complete a case report form for each child (online or print form), including demographic characteristics for the child, diagnostic test results, clinical features, treatment, and outcomes. In the CMV case report form, information about the mother is also requested, including demographic characteristics, diagnostic test results, and symptoms during pregnancy (including rash, fever, and flu‐like illness). Data from all case report forms are entered into the REDCap database.21 Minimal identifiers, including the initials and date of birth for each child, are collected to allow identification of duplicate reports, but were removed prior to data extraction and analysis.

We classified cases of congenital CMV infection as definite or suspected. The case definition for notification of definite congenital CMV infection was detection of CMV in urine, blood, saliva, or biopsy tissue collected during the first 21 days of life. Dried blood spots are increasingly used for retrospectively identifying CMV infections (Guthrie cards); cases in which a child presented with clinical features consistent with congenital CMV infection after 21 days of life were also classified as definite cases if a CMV‐positive blood spot result was available. Suspected congenital CMV infections were defined by the detection of CMV in the urine, blood, saliva, or biopsy tissue of a child up to twelve months of age, or positive CMV IgM serum results coupled with clinical features associated with intrauterine CMV infection.

The clinical features associated with congenital CMV infection assessed in the questionnaires were small for gestational age or intrauterine growth restriction, hearing loss or impairment, hepatitis, hepatomegaly, jaundice, anaemia, thrombocytopaenia, petechiae or purpura, pneumonitis, myocarditis, chorioretinitis, microphthalmia, encephalitis, microcephaly, seizures, developmental delay, delayed motor milestones, abnormality of movement or posture, cerebral palsy, and other neurological symptoms. Diagnosis of clinical sequelae consistent with congenital CMV infection was at the discretion of the reporting paediatric clinician.

We included all definite congenital CMV infections reported to the APSU during 1 January 1999 – 1 January 2024 in our analysis. Reporting of hearing loss and developmental delay was restricted to questionnaires received after 1 January 2004, when universal newborn hearing screening was adopted across Australia;18 it was recommended that infants who did not pass newborn hearing tests be tested for CMV infection, given the association with hearing loss (targeted testing).22 “Intracranial calcification” was not included in questionnaires from 1 January 2017 because of concerns about the specificity of this finding; paediatricians could still include such findings under “brain imaging results”.

The change in reported case numbers over time was analysed using unadjusted Poisson regression. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS Statistics 25.0 (IBM).

Ethics approval

The study reported in this article was approved by the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network Human Research Ethics Committee (2020/ETH03310).

Results

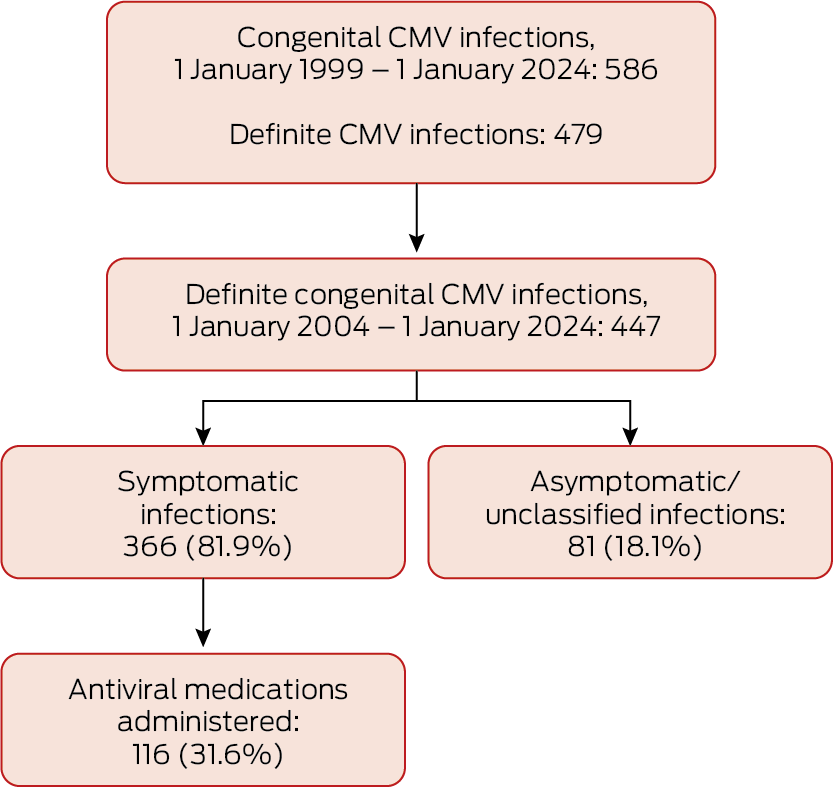

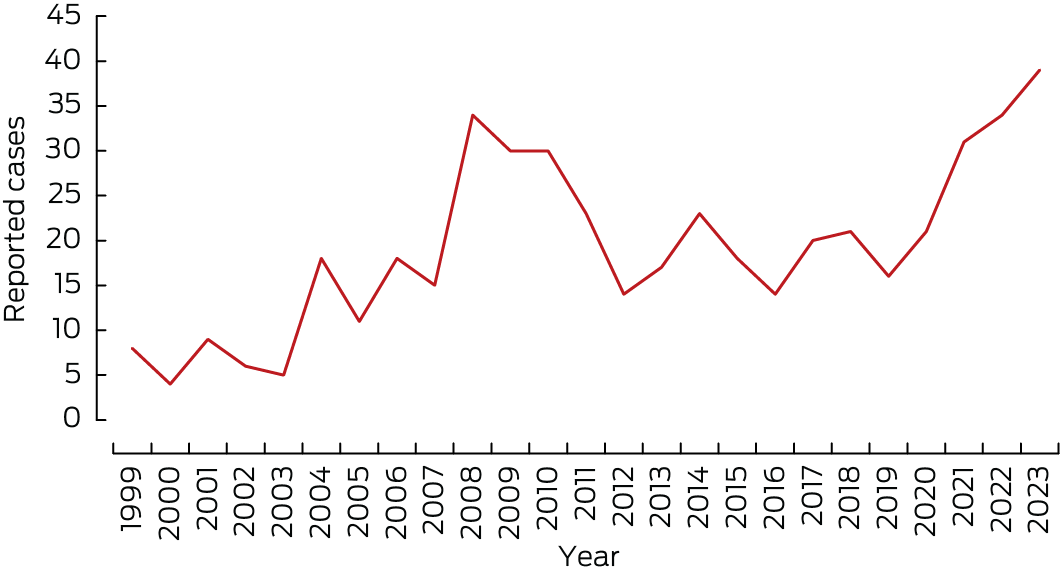

During 1 January 1999 – 1 January 2024, 586 cases of congenital CMV infection were reported to the APSU (0.008% of 7 193 242 births in Australia during this period23); the reported birth prevalence was 8.15 (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.50–8.83) infections per 100 000 births. Of the 586 cases, 479 (82%) were classified as definite congenital CMV infections; during 1 January 2004 – 1 January 2024 (ie, with universal infant hearing testing), 447 of 506 cases (88.3%) were classified as definite. The annual number of definite congenital CMV cases increased during 1 January 2004 – 1 January 2024 (per year: odds ratio, 1.21, 95% CI, 1.16 − 1.26) (Box 1, Box 2).

During 1 January 1999 – 1 January 2024, 218 of 479 definite cases (45.5%) were reported in New South Wales, 107 (22.3%) in Queensland, 43 (9.0%) in Western Australia, 42 (8.8%) in Victoria, thirteen (2.7%) in South Australia, eight (1.7%) in the Northern Territory, and seven (1.5%) in Tasmania; the state/territory was unknown for 41 cases (8.6%). The respective proportions of participating APSU clinicians and births were similar in each Australian state and territory (data not shown).

Nine neonatal deaths, two stillbirths, and one termination of pregnancy were associated with the 586 suspected or definite cases of congenital CMV infection during 1 January 1999 – 1 January 2024.

Clinical sequelae of definite congenital CMV infections

Diagnoses for the 479 infants with definite congenital CMV infections during 1 January 1999 – 1 January 2024 included small for gestational age or intrauterine growth restriction (135 infants, 28.2%); neurological conditions (most frequently: deafness [183, 38.2%], microcephaly [89, 18.6%], intracranial calcification [69, 14.4%]); liver disease with jaundice (130, 27.1%), hepatomegaly (75, 15.7%), or hepatitis (85, 14.7%); bone marrow conditions (most frequently: thrombocytopaenia [139, 29.0%], petechiae/purpura [89, 18.6%]); pneumonitis (33, 6.9%); and myocarditis (seven, 1.5%) (Box 3).

Mothers of infants with definite congenital CMV infections

Clinical results were reported to the APSU for 250 of 479 mothers of infants with definite congenital CMV infections during 1 January 1999 – 1 January 2024 (52.2%); antenatal serology results only were available for 127 women (26.5%), postnatal serology results only for 93 women (19.4%), and serology results from before pregnancy for two women (0.4%). Illnesses during pregnancy (not necessarily CMV‐related) were reported for 189 women (39.5%), including fifty‐nine who reported fever, eleven who reported rash, and 121 who reported flu‐like illnesses.

Newborn blood spot screening, hearing loss, and neurological sequelae

Among the 479 cases of definite congenital CMV infection, 168 Guthrie card tests (newborn blood spot screening) for polymerase chain reaction CMV DNA detection were reported in the questionnaires; 154 (91.7%) were CMV‐positive, of which 143 (92.9%) provided the sole reason for classifying the cases as definite (ie, diagnosed more than 21 days after birth, or cases could not be classified using other diagnostic results). Hearing loss was diagnosed in 110 infants (71.4%) with positive Guthrie card results.

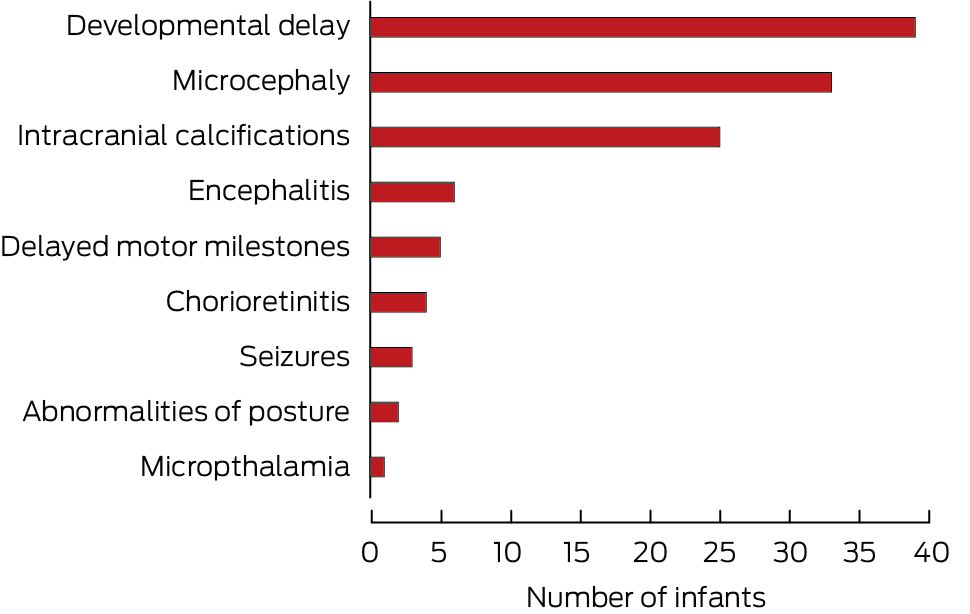

During 1 January 2004 – 1 January 2024 (ie, after the introduction of universal neonatal hearing screening), 366 of 447 definite congenital CMV infections (81.9%) were categorised as symptomatic, 178 infants (39.8%) were diagnosed with hearing loss, and 161 (36.0%) were diagnosed with neurological sequelae. Seventy‐eight infants diagnosed with hearing loss (43%) had other neurological sequelae, most frequently developmental delay (39 infants), microcephaly (33 infants), and intracranial calcification (twenty‐five infants) (Box 4). CMV‐positive Guthrie card tests were reported for 150 of 447 infants with definite congenital CMV infections during 1 January 2004 – 1 January 2024, of which 143 (95.3%) provided the sole reason for classifying the cases as definite.

Antiviral therapy

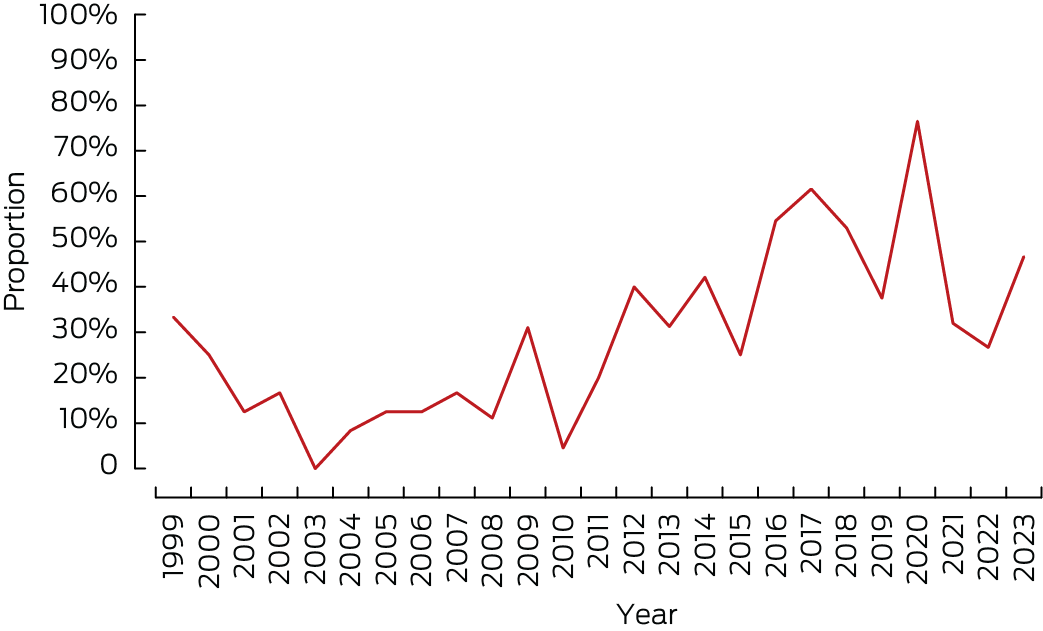

The proportion of infants with symptomatic congenital CMV infections who received antiviral treatment increased from two of six (33%) in 1999 to 14 of 30 (47%) in 2023 (Box 5) (per year: odds ratio, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01–1.06). During 1 January 2004 – 1 January 2024, 116 of 366 infants with symptomatic definite congenital CMV infections (32%) received antiviral medications, including 56 of 178 with diagnosed hearing loss (32%) and 69 of 161 with neurological sequelae (43%).

Discussion

Our analysis of data from the longest running national congenital CMV surveillance study in the world found that the incidence of definite congenital CMV infections increased during 1999–2023, that a broad range of clinical sequelae are associated with congenital CMV infections in Australia, that maternal illnesses during pregnancy and serology results are often not reported for such cases, that Guthrie cards can be effectively used for retrospectively diagnosing congenital CMV infection, and that antiviral medications were increasingly used to treat infants with symptomatic congenital CMV infections.

Congenital CMV is the leading infectious cause of congenital malformation in high income countries, including Australia, and probably also in low to middle income countries. Despite the burden of disease associated with congenital CMV infections, long term surveillance of case numbers is still not undertaken in many countries.1,8,9

The mean estimated prevalence of congenital CMV infections in developed countries is 0.65% of births.1,16 A total of 46 756 symptomatic or asymptomatic congenital CMV infections in Australia during 1999–2023 would therefore be expected; we identified 479 definite cases in our study, or 1.0% of the expected number. In Australia, universal newborn hearing screening was established in 2004.18 The number of congenital CMV infections reported to the APSU increased from 2004; infants who do not pass the hearing test or have confirmed hearing loss are tested for CMV infection.24 Improved molecular diagnostic techniques for identifying cases were also introduced at this time.25 Nevertheless, the 447 definite cases during 1 January 2004 – 1 January 2024 still comprised only 1.2% of the expected 38 650 cases for this period (5 946 193 recorded births23).

These findings could indicate that congenital CMV infections are under‐reported in Australia because of poor awareness among health care professionals of CMV infection and its implications during pregnancy. Fewer than 10% of Australian maternity care clinicians routinely provide advice on the prevention of congenital CMV infection, and they do not have the confidence or knowledge to discuss it with pregnant women.26 Further, if only 1.0% of congenital CMV infections are reported to the APSU, the overall burden of disease cannot be determined. The APSU relies on voluntary reporting by clinicians, as congenital CMV infection is not notifiable in all Australian states. Not all relevant clinicians participate in the APSU, and not all participating clinicians see cases of congenital CMV infection. Underreporting is therefore likely because of the limited reach of the APSU surveillance system.

We have reported the clinical characteristics of symptomatic congenital CMV infections that comprised 81.9% of reported definite congenital CMV infections during 2004–24. Other studies have found that 10–15% of fetal CMV infections are symptomatic.3,4,7 Despite the low incidence of reporting congenital CMV infections to the APSU, surveillance of symptomatic cases appears to be effective, including cases with severe outcomes, such as hearing loss, neurological sequelae, and death. A large proportion of cases were reported in New South Wales (45.5%), where a smaller proportion of the population resides in remote areas than in other states and territories. Antenatal care is poorer in remote areas of Australia because of the limited availability of and access to maternity care clinicians, and geographic isolation.27 This situation could lead to CMV infections not being recognised in rural and remote areas. Further, although the population of New South Wales is the largest of all Australian states (about 32% of the national population), the disproportionate number of reports to the APSU from this state probably reflects the nationally low level of case identification and reporting rather than differences in population.

Guthrie cards were the only tool for retrospectively diagnosing definite congenital CMV infection in our study. Guthrie cards can be used for polymerase chain reaction detection of CMV DNA, and they can be used for establishing the aetiology of childhood sensorineural hearing loss.28 Since 2004, all newborns in Australia are screened for hearing loss.18 More than one‐third of infants with definite congenital CMV infections during 1 January 2004 – 1 January 2024 had hearing loss, concordant with other reports about congenital CMV infection and hearing loss.16,29 Using Guthrie cards as a diagnostic tool captured otherwise undetected cases of congenital CMV infection; more than 70% of CMV‐positive Guthrie findings were used to diagnose definite congenital CMV infection in infants with hearing loss more than 21 days after birth and in cases that could not be classified using other diagnostic methods. In some cases, diagnosis was made at 6–15 years of age, informing parents about the cause of their child’s hearing loss. In the case of failed hearing screens, targeted testing for CMV would increase early detection and facilitate early therapeutic intervention.25

Newborns with symptomatic and asymptomatic congenital CMV infections are at risk of long term sequelae, particularly hearing loss and neurodevelopmental delay.16,30 We found that 43% of infants with definite congenital CMV infections and hearing loss had other neurological sequelae. Infants who fail early hearing screening should be monitored for the development of other neurological conditions that require early intervention.

Intravenous or oral antiviral treatments (ganciclovir and valganciclovir) are recommended for infants with severe neurological deficits and diagnosed within 21 days of birth with congenital CMV infection.14,31 Valganciclovir treatment (six months) is recommended for infants with congenital CMV infection with moderate to severe symptoms.10 We found that 32% of infants with symptomatic congenital CMV infections during 1 January 2004 – 1 January 2024 received antiviral treatment, and the proportion increased across this period. Earlier detection of symptomatic congenital CMV infection inform the treatment of severely affected infants, possibly improving neurological outcomes.14,31

Limitations

Collecting data at a single time point each month rather than following up infants with possible congenital CMV infection is a limitation of the APSU surveillance strategy. In developed countries such as Australia, 10–15% of fetal CMV infections result in symptomatic congenital disease; 10–15% of asymptomatic cases are followed by later onset clinical sequelae, with hearing loss the predominant manifestation.16,32 As infants were not followed up after reporting to the APSU, we could not determine the incidence of later sequelae in asymptomatic cases of congenital CMV infection. Further, asymptomatic infections are more likely to have been undetected than simply unreported; cases with more severe manifestations were therefore more likely to be included in our study. Many children with congenital CMV infections and hearing loss were probably not tested for CMV prior to 2004, and were therefore not reported to the APSU.

Conclusion

We found that congenital CMV infections are probably under‐reported in Australia, and it is therefore difficult to ascertain the associated burden of disease. A variety of clinical sequelae were reported, and the proportion of infants with symptomatic congenital CMV infections increased steadily over time. Guthrie cards can be used to retrospectively diagnose congenital CMV infections that would otherwise have been missed. In the absence of universal CMV testing of newborns, targeted CMV screening after failed hearing tests in newborns could facilitate the timely identification of congenital CMV infections and the initiation of antiviral therapy.

Box 1 – Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections reported to the Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit, 1 January 1999 – 1 January 2024*

* Definite cases: CMV detected during first 21 days of life in urine, blood, saliva, or biopsy tissue, or CMV‐positive blood spot result after 21 days of life.

Box 2 – Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections reported to the Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit, 1 January 1999 – 1 January 2024, by year*

* Definite cases: CMV detected during first 21 days of life in urine, blood, saliva, or biopsy tissue, or CMV‐positive blood spot result after 21 days of life.

Box 3 – Clinical sequelae of 479 definite congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections reported to the Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit, 1 January 1999 – 1 January 2024

|

Characteristic |

Number |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Girls |

249 (52.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Boys |

224 (46.8%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Unknown/missing data |

6 (1.3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Symptomatic CMV infection |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Yes |

394 (81.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

No |

81 (17.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Unknown/missing data |

4 (1.9%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Received antiviral therapy |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Yes |

124 (25.9%) |

||||||||||||||

|

No |

313 (65.3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Unknown/missing data |

42 (8.8%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Clinical sequelae |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Small for gestational age/intrauterine growth restriction |

135 (28.2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Neurological conditions |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Microcephaly |

89 (18.6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Deafness |

183 (38.2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Encephalitis |

14 (2.9%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Chorioretinitis |

15 (3.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Microphthalmia |

2 (0.4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Intracranial calcification* |

69 (14.4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Seizures |

10 (2.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Developmental delay |

59 (12.3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Delayed motor milestones |

6 (1.3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Abnormalities of posture |

2 (0.4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Hepatic conditions |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Hepatitis |

85 (14.7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Jaundice |

130 (27.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Hepatomegaly |

75 (15.7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Bone marrow‐related conditions |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Anaemia |

46 (9.6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Thrombocytopaenia |

139 (29.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Thrombocytopaenic petechiae/purpura |

89 (18.6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Splenomegaly |

68 (14.2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Pneumonitis |

33 (6.9%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Myocarditis |

7 (1.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Not included in questionnaires from 1 January 2017. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 29 January 2025, accepted 24 July 2025

- Ece Egilmezer1

- Suzy M Teutsch2,3

- Carlos Nunez2,3

- Stuart T Hamilton4

- Adam W Bartlett5

- Pamela Palasanthiran5

- Elizabeth J Elliott3,6

- William D Rawlinson4

- 1 UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 2 Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit, Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW

- 3 The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 4 South Eastern Sydney Local Health District, NSW Health, Sydney, NSW

- 5 Sydney Children’s Hospital Randwick, Sydney, NSW

- 6 Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley – University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Data Sharing:

The de‐identified data we analysed are not publicly available.

Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit (APSU) communicable disease studies, including that of congenital CMV infections, are funded by the Australian Department of Health and Aged Care (Health/21‐22/D21‐5425703; Health/D24‐1585167). Elizabeth J Elliott received a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator grant (APP2026176). The APSU receives in‐kind support from the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (Paediatricians and Child Health Division), the Faculty of Medicine and Health, Sydney Medical School, and Specialty of Child and Adolescent Health at the University of Sydney, and Kids Research at the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network (Children’s Hospital at Westmead). We acknowledge the sustained contribution of all Australian paediatricians and other child health professionals who participate in APSU surveillance studies. We particularly thank those who reported cases of congenital CMV infection. We acknowledge current and former APSU staff. [Correction added on 19 September 2025, after first online publication: The Acknowledgements section has been updated.]

No relevant disclosures.

Author contributions:

Ece Egilmezer: methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing (original draft), writing (review and editing), visualisation. Suzy M Teutsch: methodology, formal analysis, data curation, writing (review and editing), project administration. Carlos Nunez: methodology, formal analysis, data curation, writing (review and editing), project administration. Stuart T Hamilton: data curation, writing (review and editing). Adam W Bartlett: writing (review and editing). Pamela Palasanthiran: writing (review and editing). Elizabeth J Elliott: conceptualization, methodology, writing (review and editing), supervision, funding acquisition. William D Rawlinson: conceptualization, methodology, writing (review and editing), supervision, funding acquisition.

- 1. Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta‐analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol 2007; 17: 253‐276.

- 2. Lanzieri TM, Dollard SC, Bialek SR, Grosse SD. Systematic review of the birth prevalence of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in developing countries. Int J Infect Dis 2014; 22: 44‐48.

- 3. Munro SC, Trincado D, Hall B, Rawlinson WD. Symptomatic infant characteristics of congenital cytomegalovirus disease in Australia. J Paediatr Child Health 2005; 41: 449‐452.

- 4. Grosse SD, Fleming P, Pesch MH, Rawlinson WD. Estimates of congenital cytomegalovirus‐attributable infant mortality in high‐income countries: a review. Rev Med Virol 2024; 34: e2502.

- 5. Noyola DE, Demmler GJ, Nelson CT, et al. Houston Congenital CMV Longitudinal Study Group. Early predictors of neurodevelopmental outcome in symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. J Pediatr 2001; 138: 325‐331.

- 6. Boppana SB, Fowler KB, Vaid Y, et al. Neuroradiographic findings in the newborn period and long‐term outcome in children with symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatrics 1997; 99: 409‐414.

- 7. Revello MG, Zavattoni M, Furione M, et al. Diagnosis and outcome of preconceptional and periconceptional primary human cytomegalovirus infections. J Infect Dis 2002: 553‐557.

- 8. Mussi‐Pinhata MM, Yamamoto AY, Moura Brito RM, et al. Birth prevalence and natural history of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in a highly seroimmune population. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49: 522‐528.

- 9. Lazzaro A, Vo ML, Zeltzer J, et al. Knowledge of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) in pregnant women in Australia is low, and improved with education. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2019; 59: 843‐849.

- 10. Rawlinson WD, Boppana SB, Fowler KB, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy and the neonate: consensus recommendations for prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17: e177‐e188.

- 11. Jenks JA, Nelson CS, Roark HK, et al. Antibody binding to native cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B predicts efficacy of the gB/MF59 vaccine in humans. Sci Transl Med 2020; 12: eabb3611.

- 12. Bernstein DI, Munoz FM, Callahan ST, et al. Safety and efficacy of a cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B (gB) vaccine in adolescent girls: a randomized clinical trial. Vaccine. 2016; 34: 313‐319.

- 13. Akingbola A, Adegbesan A, Adewole O, et al. The mRNA‐1647 vaccine: a promising step toward the prevention of cytomegalovirus infection (CMV). Hum Vaccin Immunother 2025; 21: 2450045.

- 14. Kimberlin DW, Jester PM, Sánchez PJ, et al. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. Valganciclovir for symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus disease. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 933‐943.

- 15. Boppana SB, van Boven M, Britt WJ, et al. Vaccine value profile for cytomegalovirus. Vaccine 2023; 41 (Suppl 2): S53‐S75.

- 16. Bartlett AW, Hall BM, Palasanthiran P, et al. Recognition, treatment, and sequelae of congenital cytomegalovirus in Australia: an observational study. J Clin Virol 2018; 108: 121‐125.

- 17. Naing ZW, Scott GM, Shand A, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy: a review of prevalence, clinical features, diagnosis and prevention. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2016; 56: 9‐18.

- 18. McMullan BJ, Palasanthiran P, Jones CA, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus: time to diagnosis, management and clinical sequelae in Australia: opportunities for earlier identification. Med J Aust 2011; 194: 625‐629. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2011/194/12/congenital‐cytomegalovirus‐time‐diagnosis‐management‐and‐clinical‐sequelae

- 19. Teutsch SM, Nunez CA, Morris A, et al. Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit (APSU) annual surveillance report 2022. Commun Dis Intell (2018) 2023; 47.

- 20. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ 2007; 85: 867‐872.

- 21. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. REDCap Consortium. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019; 95: 103208.

- 22. Palasanthiran P, Starr M, Jones C, Giles M, editors. Management of perinatal infections; third edition. Sydney: Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases, 2022. https://asid.net.au/s/ASID‐Management‐of‐Perinatal‐Infections‐3rd‐Edition.pdf (viewed Aug 2025).

- 23. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Births, Australia, 2023. 16 Oct 2024. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/births‐australia/latest‐release (viewed May 2025).

- 24. Rawlinson WD, Palasanthiran P, Hall B, et al. Neonates with congenital cytomegalovirus and hearing loss identified via the universal newborn hearing screening program. J Clin Virol 2018; 102: 110‐115.

- 25. Barbi M, Binda S, Caroppo S, Primache V. Neonatal screening for congenital cytomegalovirus infection and hearing loss. J Clin Virol 2006; 35: 206‐209.

- 26. Shand AW, Luk W, Nassar N, et al. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and pregnancy‐potential for improvements in Australasian maternity health providers’ knowledge. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2018; 31: 2515‐2520.

- 27. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Mothers who live in remote areas and their babies. In: Australia’s health 2022: data insights (cat. no. AUS 240). 7 July 2022. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/05b3ddcc‐b432‐4c10‐9aa3‐a0146e0484e0/aihw‐aus‐240_Chapter_9.pdf.aspx (viewed Aug 2025).

- 28. Boudewyns A, Declau F, Smets K, et al. Cytomegalovirus DNA detection in Guthrie cards: role in the diagnostic work‐up of childhood hearing loss. Otol Neurotol 2009; 30: 943‐949.

- 29. Bartlett AW, McMullan B, Rawlinson WD, Palasanthiran P. Hearing and neurodevelopmental outcomes for children with asymptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: a systematic review. Rev Med Virol 2017; 27: e1938.

- 30. Dollard SC, Grosse SD, Ross DS. New estimates of the prevalence of neurological and sensory sequelae and mortality associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol 2007; 17: 355‐363.

- 31. Ross SA, Kimberlin D. Clinical outcome and the role of antivirals in congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Antiviral Res 2021; 191: 105083.

- 32. Goderis J, Keymeulen A, Smets K, et al. Hearing in children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection: results of a longitudinal study. J Pediatr 2016; 172: 110‐115.

Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the birth prevalence, clinical manifestations, and management of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections in Australia, 1999–2023.

Study design: Longitudinal observational study; analysis of prospectively collected Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit (APSU) data.

Setting, participants: Australia, 1 January 1999 – 1 January 2024.

Major outcome measures: Number of definite congenital CMV infections during study period and after the establishment of universal neonatal hearing screening (1 January 2004); clinical sequelae of definite infections; proportion of infants with symptomatic definite infections treated with antiviral medications.

Results: During 1 January 1999 – 1 January 2024, 586 cases of congenital CMV infection were reported to the APSU (8.15 [95% confidence interval, 7.50–8.83] infections per 100 000 births), including 479 definite infections (82%). The most frequent sequelae of definite infections were small for gestational age or intrauterine growth restriction (135 infants, 28.2%); neurological conditions (most frequently: deafness [183, 38.2%], microcephaly [89, 18.6%]); liver disease with jaundice (130, 27.1%), hepatomegaly (75, 15.7%), or hepatitis (85, 14.7%); and bone marrow conditions (most frequently: thrombocytopaenia [139, 29.0%], petechiae/purpura [89, 18.6%]). Of 168 Guthrie card tests (newborn blood spot screening), 154 (91.7%) were CMV‐positive (polymerase chain reaction DNA detection), including 143 that provided the sole reason for classifying the cases as definite congenital CMV infections. During 1 January 2004 – 1 January 2024, 447 of 506 cases (88.3%) were definite congenital CMV infections, of which 366 (81.9%) were symptomatic; 116 of these infants (32%) were treated with antiviral medications.

Conclusions: The number of reported definite congenital CMV infections during 1 January 1999 – 1 January 2024 was only 1.0% of the number expected in Australia on the basis of their estimated prevalence in developed countries. The number of reported cases has continuously increased since 1999, as has the use of antiviral therapy. Surveillance of congenital CMV infections, the major infectious cause of congenital malformations, needs to be expanded to fully assess their prevalence and the associated disease burden, and to inform prevention strategies.