Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) is any computer system capable of generating text, images, or other types of content, often in response to a prompt or question entered through a chat interface. GenAI comprises large language models (LLMs) and other general‐purpose foundation models powered mostly by generative pre‐trained transformer (GPT) deep learning technology. Compared with traditional AI models using single data modalities for specific classification or prediction tasks, GenAI comprises task‐agnostic, increasingly multimodal models that learn shared representations of different data types and, using suitable prompts, may perform never‐before‐seen tasks.1 GenAI tools (also termed solutions or applications) are compelling because, unlike traditional AI, they are conversant, interacting directly with humans and generating human‐like responses to prompts. These tools, in the form of ChatGPT and other GenAI chatbots, have very quickly captured the interest of researchers, clinicians and industry. Anecdotally, certain GenAI tools, such as ambient AI scribes and assistants, are already being used in many practice areas.2,3 In the UK, one in five general practitioners now routinely use GenAI for various tasks.4 At the time of submission, this rapid uptake was occurring with little guidance on what use cases (tasks or clinical indications) are most amenable to GenAI, how GenAI tools intended for clinical practice should be used, evaluated and governed, and how to safeguard reliability, safety, privacy, and consent.

In addressing these issues, we undertook a narrative review of existing literature, and using this evidence, we propose a phased, risk‐tiered approach to implementing GenAI tools, discuss risks and mitigations, and consider factors likely to influence adoption of GenAI by both clinicians and health services. Although GenAI encompasses both text and image generation, this review primarily focuses on text‐based applications in clinical practice, with image‐related applications limited to report generation rather than image generation. Box 1 contains a glossary of terms used when describing GenAI.

Methods

We searched PubMed and Google Scholar for articles published between 1 January 2022 and 31 August 2024 using search terms “generative AI”, “large language models”, “clinical practice” or “health care”. We focused on review articles and grouped them into key application domains to inform our implementation framework: clinical documentation (16), operational efficiency (20), patient safety (11), clinical decision making (42), and patient self‐care (4). Seven reviews covering all these domains were also retrieved.5,6,7,8,9,10,11 From these reviews, we extracted references outlining the problem(s) being addressed and exemplars of implemented GenAI tools used to solve them. We noted considerable heterogeneity in study design and methodological rigour and relative paucity of real‐world implementations across several domains.

A phased approach to GenAI implementation

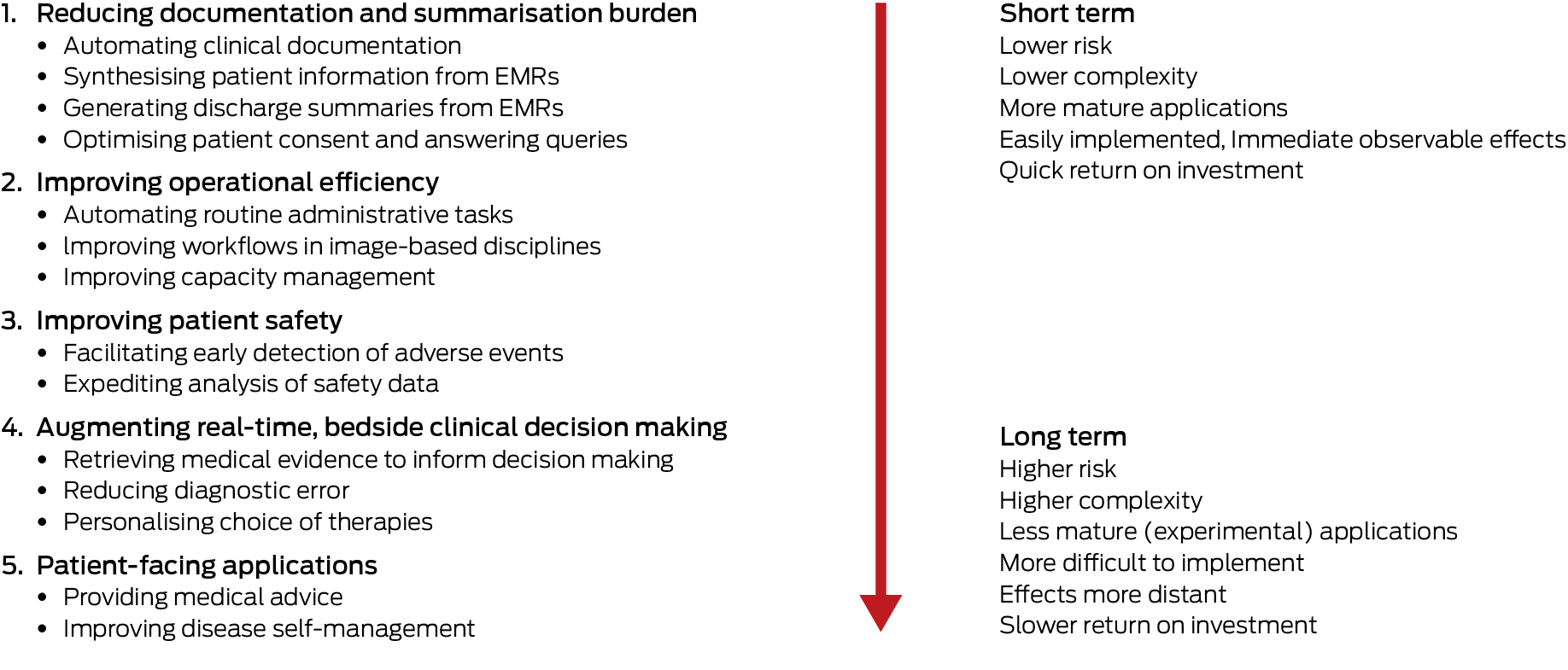

Despite the aforementioned limitations in current evidence, our review suggests that GenAI tools could be implemented over five phases (Box 2). These are sequenced according to increasing levels of patient risk, task complexity, and implementation effort, and decreasing levels of current technical maturity and evidence of safety and effectiveness. The phased approach affords careful introduction of GenAI, beginning with tools that primarily enhance administrative efficiency (lower patient risk), progressing to those directly influencing clinical decisions and patient self‐care (higher patient risk and requiring regulatory approval).

Phase 1: relieving clerical and administrative burden by providing documentation and summarisation functions

Automating clinical documentation: Doctors in clinics can spend up to 2 hours on documentation for each hour of direct clinician–patient interaction;12 hospital residents and nurses spend up to 25%13 and 60%14 respectively of shift time on documentation. Ambient GenAI tools capable of voice transcription and note generation during doctor–patient encounters can decrease documentation time up to 25% (“keyboard liberation”),15,16,17 and allow more attentiveness to patients. Similarly, scribes in nurse–patient encounters can double the time the nurse spends on direct patient care.18 Ambient GenAI tools can also generate a readily understood patient summary,19 potentially increasing satisfaction and adherence with care. Ambient scribes could also include real‐time advice, such as highlighting missed items in history or overlooked investigation results.20

Synthesising patient information from medical records: When interviewing new patients in the clinic or on ward rounds, clinicians can spend up to a third of the encounter retrieving, reading and synthesising patient summaries from electronic medical records (EMRs) before patient contact.21 GenAI can generate easily interpreted summaries of pertinent history, investigation results and treatments more accurately than clinicians22 while reducing this familiarisation time by around 20%.23

Generating discharge summaries from EMRs: Writing discharge summaries is time consuming, error prone and often slow in reaching recipients,24 with suboptimal patient outcomes.25 GenAI can generate summaries more accurate than those of junior doctors in 90% of cases,26 are available at discharge,27 and lessen the time seniors spend in supervision for complex cases by a third.28

Optimising consent: The reading grades (school‐grade level of reading skill required for understanding) of most consent forms exceed the population average (8th grade) and often lack procedure‐specific information required for informed consent. Clinicians can use GenAI chatbots that, by inputting clinician‐verified text, could provide more comprehensible, informative and empathetic versions that take less time to read.29

Phase 2: improving operational efficiency

Automating routine administrative tasks: Scheduling clinic appointments, organising staff rosters, drafting minutes and policy documents, and coding patient records are all labour‐intensive but potentially automatable tasks. As examples, GenAI could more quickly create safer and fairer rosters,30 expedite coding for faster remuneration,31 and improve operational decision making.32

Improving hospital capacity management: Overcrowded emergency departments, access block to inpatient beds, delayed discharges and avoidable readmissions are commonplace. GenAI‐enabled patient triage and discharge planning33,34 and command and control patient flow systems could assist clinicians and bed managers in optimising bed use.35

Improving workflows in image‐based disciplines: Taking radiology as the most mature domain, heavy workloads stress radiologists and cause delays in issuing reports, which can compromise patient care.36 Tools that automate image interpretation and structured reporting37 can reduce total reporting time by a third,38 reducing radiologist burnout and shortening report turnaround times.39 GenAI could potentially optimise referral and reporting prioritisation, patient scheduling and preparedness, and scan protocoling.40 Similar benefits in prioritising, interpreting and reporting digital pathology slides could also be realised with GenAI.41

Phase 3: assisting quality and safety improvement

Facilitating gathering and trending of data: Care‐related near misses or adverse events such as medication harm and delirium are currently ascertained retrospectively from medical records or incident reports, with significant lag times. Such data could be captured, quantified and trended in real‐time using LLMs applied to EMRs, thus facilitating more timely recognition of unsafe situations warranting remedial intervention.42,43,44

Expediting analysis of data: Considerable time and effort are spent in gathering, analysing and reporting quality and safety measures, incident data, and undertaking root cause analyses, with often little impact on care.45,46 GenAI could aggregate and analyse these data more efficiently,47 identify safety hazards and contributors more quickly, automate audit48 and survey analyses,49 and allow quality and safety staff to redirect resources to proactive safety improvement.50

Phase 4: augmenting clinical decision making

Retrieving medical evidence to inform decision making: Current online literature search systems (eg, PubMed) take time to search and synthesise data, are limited to simple keyword queries, and often retrieve limited relevant, actionable reports.51 GenAI, particularly using retrieval augmented generation, can very quickly and iteratively, in response to serial prompts, screen available literature and synthesise high quality, actionable evidence with supporting references,52 although the ability of LLMs to assess risk of bias of clinical trials remains limited.53

Reducing diagnostic error: Diagnostic error accounts for 60–70% of all medical errors causing harm, mostly caused by cognitive biases in reasoning.54 Responding to clinician prompts, GenAI could suggest more accurate differential diagnoses or detect and reduce misdiagnosis,55 particularly for complex, undifferentiated general medical cases involving non‐expert clinicians.56

Personalising therapies: The response of many patients to specific therapies for diagnosed and confirmed diseases remains unpredictable.57 Applying GenAI to EMRs and genomic databases could identify patient genotypes or phenotypes associated with favourable or unfavourable treatment responses, as seen in various oncological applications.58

Phase 5: assisting laypeople in self‐triage, self‐diagnosis and self‐management of ill health

More rigorous evaluation will be required of consumer‐facing applications relying on the do‐it‐yourself proficiency of users who may lack medical expertise, especially as GenAI chatbots could give seemingly confident, personalised but inappropriate advice.59

Providing medical advice: GenAI symptom checkers can diagnose conditions better than laypeople using traditional online information sources, but remain inferior to vetting by clinicians, with triage decisions for acute conditions particularly problematic.60 However, GenAI chatbots fine‐tuned on curated medical knowledge could reliably identify patients’ needs and provide informed suggestions.61 Chatbots that can process and draft responses to messages and queries of patients with diagnosed conditions under the care of clinicians can also alleviate clinician burden and enhance patient engagement.62

Improving chronic disease self‐management: The use of GenAI chatbots to manage chronic diseases seems well accepted by patients in supporting mental health, physical activity and behaviour change for selected conditions,63 but evidence of effects on patient outcomes is limited.64 Wearable devices integrated with GenAI can potentially detect adverse health states such as falls or clinical deterioration.65

Risks to safety and quality of care in GenAI implementation

Several risks to patient safety and quality of care require careful consideration.66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73 These relate to: reliability (errors, hallucinations); consistency (different responses to the same question); explainability (few rationales for responses); limited understanding of context; biased responses due to unrepresentative training data; misuse of prompts; potential privacy breaches; little auditability of tool processes and outputs; workflow disruptions and job displacement; depersonalised care; over‐reliance of clinicians on GenAI with clinician de‐skilling; limited clinician and patient acceptance; and costs and carbon footprint. However, risk mitigation strategies exist and will continue to evolve (Box 3).

Although many of these risks are common to all forms of AI, certain risks, such as hallucinations, prompt misuse and the inability to be audited, are peculiar to GenAI. GenAI is also not yet capable of higher‐order reasoning, contextual understanding, capturing sensory and nonverbal cues, or making moral or ethical judgements. Decision support LLMs may produce inconsistent advice to the same queries and be as prone to cognitive biases as humans.74 GenAI alters its behaviour in response to new data inputs or updating or recalibration of its operations, which may go unannounced. Importantly, in performing several different tasks, acceptable GenAI performance on one “benchmark” task does not translate to other, seemingly related tasks for which it was not trained.75 This challenges the generalisability of any single, point in time evaluation of an evolving model with a large potential task capability. Ensuring the quality of massive datasets used to train GenAI models is challenging compared with traditional AI models trained on smaller, targeted datasets. The behaviour of hugely complex LLMs with billions of parameters performing different tasks cannot be understood, despite knowing their technical architecture.

Regulatory options

Evaluation and regulation of GenAI tools with their limitless and changing arrays of inputs and outputs is hugely challenging. A single, fit‐for‐purpose pre‐deployment assessment and approval of all GenAI tools, as software as a medical device (SaMD), may not suffice for tools that continue to learn and adapt. Currently the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) regulates some but not all AI tools designed to support clinical decision making as SaMD, but exempts tools, such as GenAI scribes, which provide only documentation or administrative assistance. The TGA’s remit for consumer‐facing AI tools remains undefined. Current regulatory and accreditation processes,76 coupled with amendments in society‐wide laws (eg, privacy, consumer and anti‐discrimination laws) may be sufficient to cover many GenAI applications.

Two regulatory approaches are possible: an application‐centric approach, and a system‐centric approach. In an application‐centric approach, individual tools are evaluated according to task criticality and patient risk. For high risk diagnostic or treatment applications (phases 4 and 5), the tool may be frozen pre‐deployment and evaluated in a standard pathway (versus a fast pathway) using pragmatic clinical trials (Box 4).77,78,79 If approved, the tool could later be locked down, re‐opened, retrained (if needed), and re‐evaluated for re‐approval if any substantive change in function or deviation from benchmark tasks is seen. The US Food and Drug Administration calls for AI developers to provide an algorithm change protocol describing how modifications are generated and validated.80 Lower risk tools (phases 1 and 2) may pass through a fast pathway, requiring only observational studies or post‐deployment verification studies for approval. A standardised, actionable, risk‐based checklist for evaluating GenAI along multiple axes, including post‐deployment monitoring of real‐world performance and clinical impact, is needed81,82,83 as are similar checklists for identifying and resolving ethical concerns.84,85 Importantly, any GenAI tool must undergo a standardised clinical validation process at the local level using local data, including tools with regulatory approval. Using open‐source or open‐weight tools hosted on local servers may be the best option for protecting privacy, but requires in‐house data scientists and technical staff for model training and tool deployment.

A complementary system‐centric approach requires tool developers and deployers (ie, large‐scale health services) to wrap a quality assurance framework86 around their GenAI activities, comprising both risk mitigation (Box 3) and life cycle monitoring and evaluation. This framework may include statistical process control analyses that define acceptable bounds around tool accuracy or analyses of downstream effects on proximal clinical outcomes (eg, adverse events, mortality).87 More proxy measures of tool use, such as tracking the number of human‐initiated corrections to LLM‐created documents, could also be used.88 Developers and deployers might be accredited by an appointed authority to use GenAI tools depending on how well they measure, report and satisfy these parameters. Health services may need to establish dedicated, multidisciplinary clinical AI units to perform these tasks and provide the necessary human expertise and digital infrastructure.89 Such units may also specialise in validating and piloting specific applications before deployment in other similar or affiliated services, given the limited capacity of some services to undertake these tasks for every GenAI tool they may want to deploy.90 A balance is therefore needed between bespoke and more centralised evaluations, with the latter preferred for widely used, high value, high risk or high impact solutions.

Promoting adoption of GenAI

Because of its human‐like interactivity, GenAI is rapidly gaining acceptance by frontline clinicians for certain tasks (eg, ambient scribes), bringing a cultural shift in how medicine is practised and providing more value over time.91 Clinicians will likely adopt GenAI for common tasks where it has demonstrated acceptable accuracy and safety, is easy to use, aligns with clinical workflows, and enhances clinician–patient interactions.92 Clinician trust will rely on clearly articulated use cases, well defined risk‐based clinical testing processes and evidence generation, and ongoing monitoring of performance linked to original indications.93 Consumer trust will centre on tool accuracy, transparency around GenAI use in their care, and privacy assurances.94 Meaningful co‐design with diverse consumer groups can help identify concerns and build appropriate safeguards into GenAI implementation.95

All users of GenAI, both health professionals and patients, will need to be well versed, through education and training programs, in its limitations, know how to use it responsibly, consistently apply human judgement to its outputs, and undertake appropriate consent procedures in using AI in care delivery. Every GenAI tool should come with a fact sheet or model card providing information, as necessary, on its function and context, training datasets, performance metrics, bias evaluation, safety assessment, user testing, technical architecture, prompt engineering, and conditions of appropriate use.96

Our narrative review identified several organisational or system factors likely to influence GenAI uptake, with some common to all forms of AI. First is the need for interdisciplinary collaborations involving researchers, data scientists, ethicists, vendors, clinicians and consumers in co‐designing and co‐evaluating GenAI tools and ensuring they are fit for purpose. Second, health services must decide whether to adopt off‐the‐shelf GenAI open‐source or proprietary tools, with local calibration as required, or develop, or co‐develop with a vendor, tools in‐house. Whether to integrate tools with EMRs through application programming interfaces or embed them within reconfigured EMRs is another issue for EMR vendors to decide. Guidance that assists health services to assess the suitability of GenAI tools before committing to development and/or deployment is required.97 The financial and environmental impacts of software, hardware and staffing also need consideration.98 Lower cost scalability may be achieved using vertically integrated state and territory eHealth units able to collect data from multi‐site EMRs and using it to train and test their own or third‐party tools, which, if successful, are then provided to all participating services for local calibration. Third, it is crucial for industry, regulators, and health services to enhance access for developers to context‐specific patient data from EMRs and other sources for GenAI training, while controlling data misuse. Health data are currently siloed, often lack data standards, and access is reliant on multiple data custodians using different site‐specific access rules. Harmonising access processes and establishing FHIR‐enabled (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) interoperable data exchange using common data formats are essential. Fourth, introducing GenAI into clinical practice should be guided by best‐practice implementation frameworks that optimise human–computer interfaces and clinician/consumer acceptance.99,100 Fifth, clinicians’ legal liability for a poor patient outcome following their justifiable acceptance or rejection of GenAI advice must be defined and managed using strategies derived from emerging legal opinions and early experiences in implementing health care AI (Box 5).101,102,103,104,105

Future directions

This narrative review has highlighted potential gains from adopting GenAI in clinical practice. While our cited evidence may be criticised for selection bias, recent reviews published over the last two years (during which LLMs such as ChatGPT became available) were consulted, and our list of use cases is not intended to be exhaustive. As GenAI is rapidly evolving and there is a time lag between publication of original work and subsequent incorporation into review articles, we concede that some relevant primary articles may have been missed. We recognise the limitations of current GenAI106 and the urgent need for more real‐world research to grow the evidence base on the efficiency, quality and safety of GenAI‐assisted care, and identify the tasks and contexts for which this new and rapidly evolving technology is best suited. The advantage of GenAI is its flexibility across multiple tasks and its conversant, natural language interface, rather than superior performance on every task. Some tasks will be better served by fine‐tuned supervised machine learning models rather than LLMs.107 Governance and technical standards will be required coupled with rigorous evaluation frameworks that allow users to respond quickly to unanticipated consequences and hazards. We propose a phased, risk‐tiered implementation of GenAI tools into health care coupled with risk mitigation strategies. As a human invention, GenAI will never be perfect, but judicious selection and cautious introduction may considerably improve current care.108

Box 1 – Glossary

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Adversarial attacks (or jailbreaking) |

Methods designed to bypass the safety restrictions of AI models, particularly LLMs, and cause them to issue harmful or undesirable responses |

||||||||||||||

|

AI agents |

A software system capable of autonomously making decisions, planning actions and executing tasks with minimal human intervention to achieve predetermined goals |

||||||||||||||

|

Algorithm change protocol |

A predetermined step‐by‐step plan developed by an AI model developer to control anticipated model modifications within its intended use, thus avoiding the need for additional regulatory reapproval |

||||||||||||||

|

Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) |

An international Health Level 7 (HL7) standard of data interoperability that enables secure, real‐time exchange of electronic health information between different healthcare systems |

||||||||||||||

|

Fine‐tuning |

Process of adapting a pre‐trained model for specific tasks using domain‐specific data |

||||||||||||||

|

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) |

AI systems that can create new content (text, images, etc.) based on patterns learned from data |

||||||||||||||

|

Generative pre‐trained transformer (GPT) |

A specific deep learning architecture of LLM developed by OpenAI |

||||||||||||||

|

Hallucination |

When AI generates plausible but factually incorrect information |

||||||||||||||

|

Large language model (LLM) |

A type of AI model trained on vast text data to understand and generate human‐like language |

||||||||||||||

|

Model card |

Documentation that provides information about a model’s capabilities, limitations and intended uses |

||||||||||||||

|

OpenAI |

An American AI research and deployment company that aims to ensure AI systems that are generally smarter than humans benefit all of humanity |

||||||||||||||

|

Prompt engineering |

Crafting specific instructions to elicit desired responses from GenAI |

||||||||||||||

|

Red teaming |

A process where a group of cybersecurity experts (“red team”) simulates real‐world cyberattacks to assess a data system’s defences, identify weaknesses, and improve its ability to detect and respond to actual threats |

||||||||||||||

|

Retrieval augmented generation |

Technique that improves accuracy and relevance of LLM responses by retrieving and incorporating external knowledge into the model context |

||||||||||||||

|

Task‐agnostic |

AI system or function that is not dependent on or specific to a particular task, and is able to be used or applied to a broad array of tasks or environments without requiring task‐specific knowledge |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Phased implementation of generative artificial intelligence (Gen AI)

EMRs = electronic medical records.

Box 3 – Risk mitigation strategies for using generative artificial intelligence (GenAI)

|

Risk |

Mitigation strategy |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Data quality (biased, inaccurate, unrepresentative or altered training datasets) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Data privacy |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Output errors and hallucinations |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Lack of human vigilance of model outputs (akin to automation complacency) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Misuse of prompts (resulting in harmful, biased or unintended content – termed adversarial attacks or jailbreaking) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Model transparency and validation |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Clinician and patient acceptance |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Financial and environmental sustainability |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

EMR = electronic medical record. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Methods for generating evidence of effectiveness of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Pre‐implementation stage:

|

|||||||||||||||

Implementation testing stage:

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Clinical validation stage (by risk level):

For higher risk applications (phases 4 and 5):

|

|||||||||||||||

Ongoing monitoring stage:

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

RCT = randomised controlled trial. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Strategies for managing medicolegal risk in using generative artificial intelligence (GenAI)

|

|

|||||||||||||||

At the level of individual clinicians and/or health care organisations:

|

|||||||||||||||

At the level of industry and stakeholder groups (group practices, health services, developers/vendors):

|

|||||||||||||||

At the level of the Therapeutic Goods Administration or organisational accrediting body:

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Scott IA, Zuccon G. The new paradigm in machine learning ‐ foundation models, large language models and beyond: a primer for physicians. Intern Med J 2024; 54: 705‐715.

- 2. Knibbs J. AI scribe wars heating up. Health Services Daily, 24 Sept 2024. https://www.healthservicesdaily.com.au/ai‐scribe‐wars‐heating‐up/19900 (viewed Dec 2024).

- 3. Knibbs J. GP AI scribe use more than doubles in four months. Medical Republic, 4 Oct 2024. https://www.medicalrepublic.com.au/gp‐ai‐scribe‐use‐more‐than‐doubles‐in‐four‐months/111429 (viewed Dec 2024).

- 4. Blease CR, Locher C, Gaab J, et al. Generative artificial intelligence in primary care: an online survey of UK general practitioners. BMJ Health Care Inform 2024; 31: e101102.

- 5. Garg RK, Urs VL, Agarwal AA, et al. Exploring the role of ChatGPT in patient care (diagnosis and treatment) and medical research: a systematic review. Health Promot Perspect 2023; 13: 183‐191.

- 6. Wang L, Wan Z, Ni C, et al. A systematic review of ChatGPT and other conversational large language models in healthcare [preprint]. medRxiv; 27 Apr 2024. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.26.24306390.

- 7. Dave T, Athaluri SA, Singh S. ChatGPT in medicine: an overview of its applications, advantages, limitations, future prospects, and ethical considerations. Front Artif Intell 2023; 6: 1169595.

- 8. Pressman SM, Borna S, Gomez‐Cabello CA, et al. Clinical and surgical applications of large language models: a systematic review. J Clin Med 2024; 13: 3041.

- 9. Moulaei K, Yadegari A, Baharestani M, et al. Generative artificial intelligence in healthcare: a scoping review on benefits, challenges and applications. Int J Med Inform 2024; 188: 105474.

- 10. Ghebrehiwet I, Zaki N, Damseh R, Mohamad MS. Revolutionizing personalized medicine with generative AI: a systematic review. Artif Intell Rev 2024; 57: 128.

- 11. Park YJ, Pillai A, Deng J, et al. Assessing the research landscape and clinical utility of large language models: a scoping review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2024; 24: 72.

- 12. Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med 2016; 165: 753‐760.

- 13. Mamykina L, Vawdrey DK, Hripcsak G. How do residents spend their shift time? A time and motion study with a particular focus on computers. Acad Med 2016; 91: 827‐832.

- 14. Khamisa N, Peltzer K, Oldenburg B. Burnout in relation to specific contributing factors and health outcomes among nurses: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013; 10: 2214‐2240.

- 15. Balloch J, Sridharan S, Oldham G, et al. Use of an ambient artificial intelligence tool to improve quality of clinical documentation. Future Healthc J 2024;11: 100157.

- 16. Tierney AA, Gayre G, Hoberman B, et al. Ambient artificial intelligence scribes to alleviate the burden of clinical documentation. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv 2024; 5: CAT.23.0404.

- 17. Liu T, Hetherington TC, Stephens C, et al. AI‐powered clinical documentation and clinicians’ electronic health record experience: a nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2024; 7: e2432460.

- 18. Dicuonzo G, Donofrio F, Fusco A, Shini M. Healthcare system: moving forward with artificial intelligence. Technovation 2023; 120: 102510.

- 19. Ali SR, Dobbs TD, Hutchings HA, Whitaker IS. Using ChatGPT to write patient clinic letters. Lancet Digit Health 2023; 5: e179‐181.

- 20. Seth P, Carretas R, Rudzicz F. The utility and implications of ambient scribes in primary care. JMIR AI 2024; 3: e57673.

- 21. Overhage JM, McCallie D. Physician time spent using the electronic health record during outpatient encounters. a descriptive study. Ann Intern Med 2020; 172: 169‐174.

- 22. Van Veen D, Van Uden C, Blankemeier L, et al. Adapted large language models can outperform medical experts in clinical text summarization. Nat Med 2024; 30: 1134‐1142.

- 23. Chi EA, Chi G, Tsui CT, et al. Development and validation of an artificial intelligence system to optimize clinician review of patient records. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4: e2117391.

- 24. Robelia PM, Kashiwagi DT, Jenkins SM, et al. Information transfer and the hospital discharge summary: national primary provider perspectives of challenges and opportunities. J Am Board Fam Med 2017; 30: 758‐765.

- 25. Li JYZ, Yong TY, Hakendorf P, et al. Timeliness in discharge summary dissemination is associated with patients’ clinical outcomes. J Eval Clin Pract 2013; 19: 76‐79.

- 26. Clough RAJ, Sparkes WA, Clough OT, et al. Transforming healthcare documentation: harnessing the potential of AI to generate discharge summaries. BJGP Open 2024; 8: BJGPO.2023.0116.

- 27. Williams CYK, Bains J, Tang T, et al. Evaluating large language models for drafting emergency department encounter summaries. PLOS Digit Health 2025; 4: e0000899.

- 28. Barak‐Corren Y, Wolf R, Rozenblum R, et al. Harnessing the power of generative AI for clinical summaries: perspectives from emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med 2024; 84: 128‐138.

- 29. Decker H, Trang K, Ramirez J, et al. Large language model‐based chatbot vs surgeon‐generated informed consent documentation for common procedures. JAMA Netw Open 2023; 6: e2336997.

- 30. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Using AI to create work schedules significantly reduces physician burnout, study shows. Schaumburg, IL: ASA, 28 Jan 2022. https://www.asahq.org/about‐asa/newsroom/news‐releases/2022/01/using‐ai‐to‐create‐work‐schedules‐significantly‐reduces‐physician‐burnout (viewed May 2024).

- 31. Chomutare T, Svenning TO, Hernández MÁT, et al. Artificial intelligence to improve clinical coding practice in Scandinavia: crossover randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2025; 27: e71904.

- 32. Liu J, Capurro D, Nguyen A, Verspoor K. Early prediction of diagnostic‐related groups and estimation of hospital cost by processing clinical notes. NPJ Digit Med 2021; 4: 103.

- 33. Paslı S, Şahin AS, Beşer MF, et al. Assessing the precision of artificial intelligence in ED triage decisions: insights from a study with ChatGPT. Am J Emerg Med 2024; 78: 170‐175.

- 34. Tahayori B, Chini‐Foroush N, Akhlaghi H. Advanced natural language processing technique to predict patient disposition based on emergency triage notes. Emerg Med Australas 2021; 33: 480‐484.

- 35. Tu T, Azizi S, Driess D, et al. Towards generalist biomedical AI. NEJM AI 2024; 1.

- 36. Bailey CR, Bailey AM, McKenney AS, Weiss CR. Understanding and appreciating burnout in radiologists. RadioGraphics 2022; 42: E137–E139.

- 37. Tian D, Jiang S, Zhang L, et al. The role of large language models in medical image processing: a narrative review. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2024; 14: 1108‐1121.

- 38. Ahyad RA, Zaylaee Y, Hassan T, et al. Cutting edge to cutting time: can ChatGPT improve the radiologist’s reporting? J Imaging Inform Med 2025; 38: 346‐356.

- 39. Jones CM, Danaher L, Milne MR, et al. Assessment of the effect of a comprehensive chest radiograph deep learning model on radiologist reports and patient outcomes: a real‐world observational study. BMJ Open 2021; 11: e052902.

- 40. Pierre K, Haneberg AG, Kwak S, et al. Applications of artificial intelligence in the radiology roundtrip: process streamlining, workflow optimization, and beyond. Semin Roentgenol 2023; 58: 158‐169.

- 41. Lu MY, Chen B, Williamson DFK, et al. A multimodal generative AI copilot for human pathology. Nature 2024; 634: 466‐473.

- 42. Silverman AL, Sushil M, Bhasuran B, et al. Algorithmic identification of treatment‐emergent adverse events from clinical notes using large language models: a pilot study in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2024; 115: 1391‐1399.

- 43. Chen A, Paredes D, Yu Z, et al. Identifying symptoms of delirium from clinical narratives using natural language processing. Proc (IEEE Int Conf Healthc Inform) 2024; 2024: 305‐311.

- 44. Wiemken TL, Carrico RM. Assisting the infection preventionist: use of artificial intelligence for health care–associated infection surveillance. Am J Infect Control 2024; 52: 625‐629.

- 45. Saraswathula A, Merck SJ, Bai G, et al. The volume and cost of quality metric reporting. JAMA 2023; 329: 1840‐1847.

- 46. Shojania KG. Incident reporting systems: what will it take to make them less frustrating and achieve anything useful? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2021; 47: 755‐758.

- 47. Boussina A, Krishnamoorthy R, Quintero K, et al. Large language models for more efficient reporting of hospital quality measures. NEJM AI 2024; 1: https://doi.org/10.1056/aics2400420.

- 48. Brzezicki MA, Bridger NE, Kobetić MD, et al. Artificial intelligence outperforms human students in conducting neurosurgical audits. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2020; 192: 105732.

- 49. Ratwani RM, Bates DW, Classen DC. Patient safety and artificial intelligence in clinical care. JAMA Health Forum 2024; 5: e235514.

- 50. Ferrara M, Bertozzi G, Di Fazio N, et al. Risk management and patient safety in the artificial intelligence era: a systematic review. Healthcare (Basel) 2024; 12: 549.

- 51. Islamaj Dogan R, Murray GC, Neveol A, Lu Z. Understanding PubMed user search behavior through log analysis. Database (Oxford) 2009; 2009: bap018.

- 52. Tang L, Sun Z, Idnay B, et al. Evaluating large language models on medical evidence summarization. NPJ Digit Med 2023; 6: 158.

- 53. Cheraghi‐Sohi S, Holland F, Singh H, et al. Incidence, origins and avoidable harm of missed opportunities in diagnosis: longitudinal patient record review in 21 English general practices. BMJ Qual Saf 2021; 30: 977‐985.

- 54. Šuster S, Baldwin T, Verspoor K. Zero‐ and few‐shot prompting of generative large language models provides weak assessment of risk of bias in clinical trials. Res Synth Methods 2024; 15: 988‐1000.

- 55. Scott IA, Miller T, Crock C. Using conversant artificial intelligence to improve diagnostic reasoning: ready for prime time? Med J Aust 2024; 221: 240‐243. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2024/221/5/using‐conversant‐artificial‐intelligence‐improve‐diagnostic‐reasoning‐ready

- 56. Takita H, Kabata D, Walston SL, et al. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of diagnostic performance comparison between generative AI and physicians. NPJ Digit Med 2025; 8: 175.

- 57. Kent DM, Nelson J, Dahabreh IJ, et al. Risk and treatment effect heterogeneity: re‐analysis of individual participant data from 32 large clinical trials. Int J Epidemiol 2016; 45: 2075‐2088.

- 58. Wang C, Zhang M, Zhao J, et al. The prediction of drug sensitivity by multi‐omics fusion reveals the heterogeneity of drug response in pan‐cancer. Comput Biol Med 2023; 163: 107220.

- 59. Webster P. Medical AI chatbots: are they safe to talk to patients? Nat Med 2023; 29: 2677‐2679.

- 60. Levine DM, Tuwani R, Kompa B, et al. The diagnostic and triage accuracy of the GPT‐3 artificial intelligence model: an observational study. Lancet Digit Health 2024; 6: e555‐e561.

- 61. Li Y, Li Z, Zhang K, et al. ChatDoctor: a medical chat model fine‐tuned on a large language model meta‐AI (LLaMA) using medical domain knowledge. Cureus 2023; 15: e40895.

- 62. Laker B, Currell E. ChatGPT: a novel AI assistant for healthcare messaging ‐ a commentary on its potential in addressing patient queries and reducing clinician burnout. BMJ Lead 2024; 8: 147‐148.

- 63. Anisha SA, Sen A, Bain C. Evaluating the potential and pitfalls of AI‐powered conversational agents as humanlike virtual health carers in the remote management of noncommunicable diseases: scoping review. J Med Internet Res 2024; 26: e56114.

- 64. Kurniawan MH, Handiyani H, Nuraini T, et al. A systematic review of artificial intelligence‐powered (AI‐powered) chatbot intervention for managing chronic illness. Ann Med 2024; 56: 2302980.

- 65. Ferrara E. Large language models for wearable sensor‐based human activity recognition, health monitoring, and behavioral modeling: a survey of early trends, datasets, and challenges. Sensors (Basel) 2024; 24: 5045.

- 66. Rodman A, Kanjee Z. The promise and peril of generative artificial intelligence for daily hospitalist practice. J Hosp Med 2024; 12: 1188‐1193.

- 67. Templin T, Perez MW, Sylvia S, et al. Addressing 6 challenges in generative AI for digital health: a scoping review. PLOS Digit Health 2024; 3: e0000503.

- 68. Lambert SI, Madi M, Sopka S, et al. An integrative review on the acceptance of artificial intelligence among healthcare professionals in hospitals. NPJ Digit Med 2023; 6: 111.

- 69. Adler‐Milstein J, Redelmeier DA, Wachter RM. The limits of clinician vigilance as an AI safety bulwark. JAMA 2024; 331: 1173‐1174.

- 70. Chen Y, Esmaeilzadeh P. Generative AI in medical practice: in‐depth exploration of privacy and security challenges. J Med Internet Res 2024; 26: e53008.

- 71. Meskó B, Topol EJ. The imperative for regulatory oversight of large language models (or generative AI) in healthcare. NPJ Digit Med 2023; 6: 120.

- 72. Mökander J, Schuett J, Kirk HR, Floridi L. Auditing large language models: a three‐layered approach. AI Ethics 2023; 4: 1085‐1115.

- 73. Hatem R, Simmons B, Thornton JE. A call to address AI “hallucinations” and how healthcare professionals can mitigate their risks. Cureus 2023; 15: e44720.

- 74. Wang J, Redelmeier DA. Cognitive biases and artificial intelligence. NEJM AI 2024; 1: Alcs2400639.

- 75. Jahan I, Laskar TR, Peng C, Huang JX. A comprehensive evaluation of large Language models on benchmark biomedical text processing tasks. Comput Biol Med 2024; 171: 108189.

- 76. Fleisher LA, Economou‐Zavlanos NJ. Artificial intelligence can be regulated using current patient safety procedures and infrastructure in hospitals. JAMA Health Forum 2024; 5: e241369.

- 77. Ma Y, Achiche S, Pomey MP, et al. Adapting and evaluating an AI‐based chatbot through patient and stakeholder engagement to provide information for different health conditions: master protocol for an adaptive platform trial (the MARVIN Chatbots Study). JMIR Res Protoc 2024; 13: e54668.

- 78. Bragazzi NL, Garbarino S. Toward clinical generative AI: conceptual framework. JMIR AI 2024; 3: e55957.

- 79. Kwong JCC, Erdman L, Khondker A, et al. The silent trial — the bridge between bench‐to‐bedside clinical AI applications. Front Digit Health 2022; 4: 929508.

- 80. US Food and Drug Administration. Marketing submission recommendations for a predetermined change control plan for artificial intelligence‐enabled device software functions. Guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. 18 August, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory‐information/search‐fda‐guidance‐documents/marketing‐submission‐recommendations‐predetermined‐change‐control‐plan‐artificial‐intelligence (viewed Aug 2025).

- 81. Abbasian M, Khatibi E, Azimi I, et al. Foundation metrics for evaluating effectiveness of healthcare conversations powered by generative AI. NPJ Digit Med 2024; 7: 82.

- 82. Tripathi S, Alkhulaifat D, Doo FX, et al. Development, evaluation, and assessment of large language models (DEAL) checklist: a technical report. NEJM AI 2025; 2: Alp2401106.

- 83. Bedi S, Liu Y, Orr‐Ewing L, et al. Testing and evaluation of health care applications of large language models: a systematic review. JAMA 2025; 333: 319‐328.

- 84. Solanki P, Grundy J, Hussain W. Operationalising ethics in artificial intelligence for healthcare: a framework for AI developers. AI Ethics 2022; 3: 223‐240.

- 85. Ning Y, Teixayavong S, Shang Y, et al. Generative artificial intelligence and ethical considerations in health care: a scoping review and ethics checklist. Lancet Digit Health 2024; 6: e848‐856.

- 86. Shah NH, Halamka JD, Saria S, et al. A nationwide network of health AI assurance laboratories. JAMA 2024; 331: 245‐249.

- 87. Minne L, Eslami S, de Keizer N, et al. Statistical process control for monitoring standardized mortality ratios of a classification tree model. Methods Inf Med 2012; 51: 353‐358.

- 88. Coiera E, Fraile‐Navarro D. AI as an ecosystem — ensuring generative AI is safe and effective. NEJM AI 2024; 1: 1‐4.

- 89. Cosgriff CV, Stone DJ, Weissman G, et al. The clinical artificial intelligence department: a prerequisite for success. BMJ Health Care Inform 2020; 27: e100183.

- 90. Longhurst CA, Singh K, Chopra S, et al. A call for artificial intelligence implementation science centers to evaluate clinical effectiveness. NEJM AI 2024; 1: Alp2400223.

- 91. Jindal JA, Lungren MP, Shah NH. Ensuring useful adoption of generative artificial intelligence in healthcare. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2024; 31: 1441–1444.

- 92. Scott IA, van der Vegt A, Lane P, et al. Achieving large‐scale clinician adoption of AI‐enabled decision support. BMJ Health Care Inform 2024; 31: e100971.

- 93. Patel MR, Balu S, Pencina MJ. Translating AI for the clinician. JAMA 2024; 332: 1701‐1702.

- 94. Fera B, Sullivan JA, Varia H, Shukla M. Building and maintaining health care consumers’ trust in generative AI. Deloitte Insights, 6 June 2024. https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/health‐care/consumer‐trust‐in‐health‐care‐generative‐ai.html (viewed Dec 2024).

- 95. Carter SM, Aquino YSJ, Carolan L, et al. How should artificial intelligence be used in Australian health care? Recommendations from a citizens’ jury. Med J Aust 2024; 220: 409‐416. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2024/220/8/how‐should‐artificial‐intelligence‐be‐used‐australian‐health‐care

- 96. Gallifant J, Fiske A, Levites Strekalova YA, et al. Peer review of GPT‐4 technical report and systems card. PLOS Digit Health 2024; 3: e0000417.

- 97. Dagan N, Devons‐Sberro S, Paz Z, et al. Evaluation of AI tools in health care organizations — The OPTICA tool. NEJM AI 2024; 1: Alcs2300269.

- 98. Ueda D, Walston SL, Fujita S, et al. Climate change and artificial intelligence in healthcare: review and recommendations towards a sustainable future. Diagn Interv Imaging 2024; 105: 453‐459.

- 99. Reddy S. Generative AI in healthcare: an implementation science informed translational path on application, integration and governance. Implement Sci 2024; 19: 27.

- 100. van der Vegt AH, Scott IA, Dermawan K, et al. Implementation frameworks for end‐to‐end clinical AI: derivation of the SALIENT framework. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2023; 30: 1503‐1515.

- 101. Banja JD, Hollstein RD, Bruno MA. When artificial intelligence models surpass physician performance: medical malpractice liability in an era of advanced artificial intelligence. J Am Coll Radiol 2022; 19: 816‐820.

- 102. Maliha G, Gerke S, Cohen IG, Parikh RB. Artificial intelligence and liability in medicine: balancing safety and innovation. Milbank Q 2021; 99: 629‐647.

- 103. Smith H, Fotheringham K. Artificial intelligence in clinical decision‐making: rethinking liability. Med Law Int 2020; 20: 131‐154.

- 104. Mello MM, Guha N. Understanding liability risk from using health care artificial intelligence tools. N Engl J Med 2024; 390: 271‐278.

- 105. Bradfield OM, Mahar PD. Is AI A‐OK? Medicolegal considerations for general practitioners using AI scribes. Aust J Gen Pract 2025; 54: 304‐310.

- 106. Hager P, Jungmann F, Holland R, et al. Evaluation and mitigation of the limitations of large language models in clinical decision‐making. Nat Med 2024; 30: 2613‐2622.

- 107. Brown KE, Yan C, Li Z, et al. Large language models are less effective at clinical prediction tasks than locally trained machine learning models. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2025; 32: 811‐822.

- 108. Kohane IS. Compared with what? Measuring AI against the health care we have. N Engl J Med 2024; 391: 1564‐1566.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

No relevant disclosures.

Authors’ contributions:

Scott IA: Conceptualization, data curation, writing – original draft. Reddy S: Data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Kelly T: Writing – review and editing. Miller T: Writing – review and editing. Van der Vegt A: Writing – review and editing.