Globally, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is responsible for an estimated 33 million acute lower respiratory tract infections, resulting in 26 300 in‐hospital deaths annually in children aged 0 to 60 months.1 Children under the age of 4 years are disproportionately impacted and represent 50% of cases, with infants under the age of 6 months accounting for most of the RSV‐associated hospitalisations in Australia.2

The majority of infants hospitalised with severe RSV infection are otherwise healthy; however, certain risk factors have been identified including: younger age, prematurity, and underlying lung or heart conditions.3 First Nations children, who are at an increased risk of lung diseases (eg, asthma and bronchiectasis) compared with non‐First Nations children, also experience higher rates of RSV hospitalisation, with 789 per 100 000 affected in individuals under 5 years, nearly double the rate in non‐First Nations children (420 per 100 000).4,5,6,7

Before 2024, the short‐acting monoclonal antibody palivizumab (Synagis, Abbott Laboratories) was the only available RSV preventive in Australia for children up to 2 years of age.8 However, the high cost of palivizumab, and the need for monthly injections, limited its use to a small subgroup of infants deemed to be at increased risk of severe RSV infection.9 Further, a Western Australian study found that compliance with recommended guidelines and dosing schedules was limited.10 On 24 November 2023, nirsevimab (Beyfortus, Sanofi‐Aventis and AstraZeneca), a long‐acting monoclonal antibody, was registered with the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for prevention of RSV‐related infections in children younger than 2 years of age.11 On 20 March 2024, Abrysvo (Pfizer), a maternal RSV vaccine, was also registered with the TGA for the prevention of RSV‐related infections in infants from birth to 6 months of age.12 The availability of these two preventives has marked an era‐defining advancement in RSV prevention.

In March 2024, Western Australia was the first Australian jurisdiction to announce a state‐wide government‐funded all‐infant RSV immunisation program. From 1 April 2024 to 30 September 2024, all infants entering their first RSV season (born on or after 1 October 2023) as well as children (aged 8 to 19 months) at increased risk of severe RSV were eligible to receive nirsevimab.13 A similar program was adopted in Queensland,14 whereas New South Wales opted for a program to only protect infants at increased risk.15 Recent data indicate that these programs were associated with reduced hospitalisations and medically attended RSV infections,16,17 although ongoing evaluation is needed to determine their broader impact. In November 2024, the Australian Government announced that the maternal RSV vaccine would be available from 3 February 2025 to all pregnant women for free under the National Immunisation Program (NIP).18 In parallel, Australian jurisdictions have targeted RSV monoclonal antibody (nirsevimab) programs offered at no cost to high risk or unvaccinated newborns.18 Ongoing evaluations of the national RSV prevention program will focus on assessing its impact, cost‐effectiveness and areas for refinement.

A decision to implement RSV preventive strategies involves consideration of multiple factors including timing, logistics, efficacy, coverage and the availability of new preventives. The aim of this narrative review was to critically examine and evaluate current RSV preventive options and prevention strategies to protect infants against RSV in Australia, while also considering their implementation across diverse populations based on health care infrastructure, access and attitudes.

Methods

The literature for this article draws from diverse sources, including clinical trial data, observational studies, government health reports, press releases and websites. No systematic search strategy was employed; instead, relevant literature was identified through existing expertise and manual searches of key sources. We prioritised studies from 2023–2024 as they provided both experimental and real‐world data on the efficacy and safety of RSV preventives. Grey literature that provided insights into the socio‐economic and health care impacts of RSV prevention programs was included to offer a comprehensive understanding of the implications for public health policy in Australia.

Short‐acting RSV monoclonal antibody (palivizumab)

Before nirsevimab, palivizumab was the only available RSV immunoprophylaxis in Australia, reserved for population groups at increased risk of severe RSV infection. Clinical trials for palivizumab in infants demonstrated moderate efficacy at preventing RSV‐related hospitalisations, with an early study reporting a 55% reduction in high risk children and a 78% reduction in children with prematurity (without bronchopulmonary dysplasia).19 However, a major limitation of palivizumab is the need for monthly intramuscular injections, requiring three to six doses to maintain an adequate serum concentration throughout the RSV season,20 preventing many at‐risk individuals from receiving adequate protection. In contrast, nirsevimab, a long‐acting monoclonal antibody with a considerably longer half‐life, provides protection for a minimum of five months, with a single injection.21

Long‐acting RSV monoclonal antibody (nirsevimab)

The safety and efficacy of nirsevimab in the prevention of severe RSV infections in infants is well recognised. Nirsevimab is now approved in over 35 countries, including Australia, with measurable impact in practical settings on reducing RSV infections.22

Recent clinical data from an observational study conducted in Luxembourg in the 2023 RSV season suggests that nirsevimab significantly reduced severe RSV disease in neonates.23 Between October and December 2023, an immunisation coverage of 84% (1277 doses for 1524 births) was achieved among neonates, with a reported 69% reduction in the number of RSV‐related hospital admissions for infants under 6 months old compared with the same period in 2022. Additionally, the number of infants under 6 months of age admitted to the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) decreased by 68% during this same period.23 Similar data has emerged from Galicia, Spain, one of the pioneering regions to incorporate nirsevimab into its immunisation program. With a high coverage rate of 91.7% among 10 259 eligible infants, the program in Galicia reported an estimated 89.8% reduction in RSV‐related hospital admissions.24 Another study conducted in France demonstrated the significant impact of nirsevimab on PICU admissions in infants, with nirsevimab up to 80.6% effective in preventing RSV‐related PICU admissions.25 French surveillance data from the 2023–2024 season showed a 52.7% decrease in (all‐cause) bronchiolitis hospitalisations in infants under 3 months of age compared with 2022–2023, with the 2023–2024 season data showing the lowest number of bronchiolitis cases in this population since 2017.26 These findings are summarised in Box 1, highlighting the substantial reduction in PICU admissions and bronchiolitis hospitalisations following the introduction of nirsevimab. In a pooled analysis of observational real‐world studies, nirsevimab demonstrated 90.5% effectiveness in reducing RSV‐related hospitalisations at 150 days.27

Moreover, the number needed to immunise (NNI) to prevent one RSV‐related lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) hospitalisation was 25.27 This is similar to the NNI for rotavirus vaccines, where a deterministic transmission model in France estimated an NNI of 24.15 to 27.44 to prevent one hospitalisation.28 Such comparisons contextualise the potential of RSV immunisation programs to reduce hospital burden at a level similar to rotavirus vaccination. In a 2012 Australian study following the introduction of the rotavirus vaccine to the NIP, with a subsequent national vaccine coverage of 85%, a 71% reduction in rotavirus‐related gastroenteritis admissions was observed compared with the pre‐vaccination period.29

Reassuringly, data on safety from an infant immunisation program in the Italian region of Valle d’Aosta found that the side effects of nirsevimab were mild, with no major adverse effects reported and 89% of neonates experiencing no side effects at all.30 Among infants who received nirsevimab (N = 369), side effects included fever (6.5%) and localised injection site reactions (4%), with none necessitating additional medical visits.30 Reports of fever were based on telephone interviews at 7 and 14 days post‐administration; however, the study did not specify whether fever was measured objectively or simply parent‐reported. No instances of serious adverse effects were documented. Although this study has a small sample size, the data remain promising and offer valuable insights to inform immunisation rollouts.

The follow up of infants immunised with nirsevimab in large population groups will be important in determining the risk and severity of RSV infection in infants entering their second and subsequent RSV seasons. An observational study across 31 countries (211 sites) following children into their second RSV season reported no significant increase in medically attended RSV infections, with rates comparable to those observed during the first season.31 Additionally, children maintained detectable RSV antibody levels at several time points following nirsevimab administration, suggesting enduring immunity. In the MELODY and phase 2b trials, antibody levels were more than 140‐fold above baseline by Day 31, remained over 50‐fold higher at Day 151, and were still elevated compared to baseline at Day 361.32 However, the precise threshold for protection against future RSV infection remains uncertain, and further investigation is needed to determine the long term immunological response and whether it provides protection against future RSV infections. Nirsevimab was equally efficacious against both RSV A and B subtypes.33 Intensive molecular surveillance of various RSV strains has demonstrated a high degree of conservation of the nirsevimab binding site before and after the introduction of the antibody.33 Consequently, a single intramuscular injection of nirsevimab is anticipated to maintain high neutralisation potency, effectively neutralising over 99% of currently circulating RSV strains.34 Although these early data are promising, ongoing molecular surveillance programs over successive RSV seasons are imperative to identify and track any emerging polymorphisms that may lead to a reduction in the effectiveness of nirsevimab.

Wang and colleagues showed that primary RSV infection at the age of 6–23 months was associated with increased risk of asthma and wheeze compared with primary infection at the age of 0–6 months.35 The effects on the elderly of nirsevimab given to infants is likely to be limited, as RSV infection in older adults primarily stems from school‐age children and peers rather than infants.36

Maternal vaccines

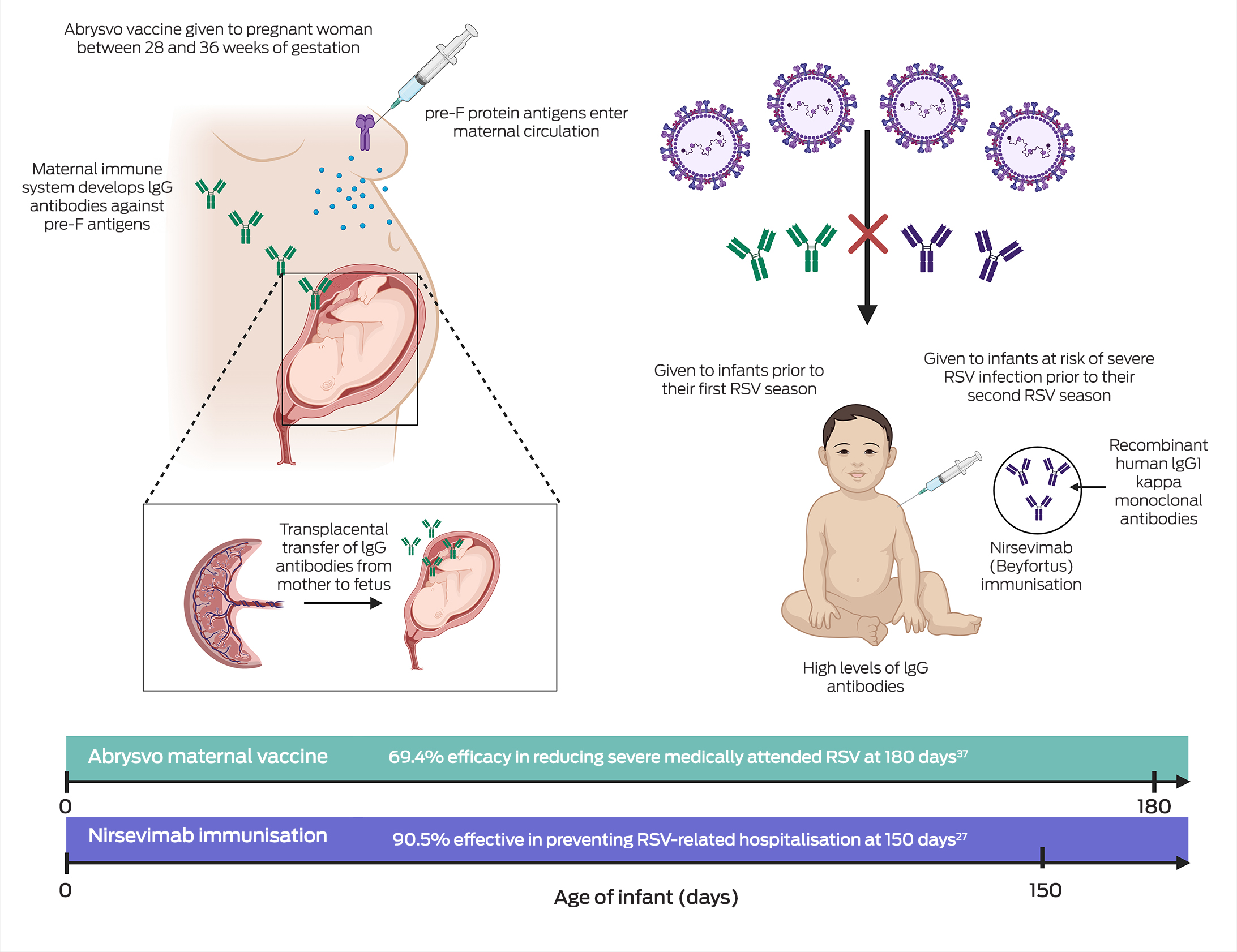

The maternal vaccine Abrysvo is another strategy for RSV prophylaxis of newborns recently added to the NIP. Maternal vaccination results in transplacental immune globulin IgG RSV antibody transfer from mother to infant,37 as illustrated in Box 2. In a phase 3, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial conducted in 18 countries (MATISSE [Maternal Immunization Study for Safety and Efficacy] study), a single dose of Abrysvo administered to 3682 pregnant women between 24 and 36 weeks of gestation was found to be 81.8% effective in preventing medically attended severe RSV disease in infants in the first 90 days of life and 69.4% effective in the first 180 days of life.37 Moreover, data from the trial demonstrated a favourable safety profile. Adverse events in infants, including those within the first month of birth, were similar between the vaccine and placebo groups.38 While a slight increase in preterm births was noted in the vaccine group, this difference was not statistically significant, and no increase in preterm birth rates was observed across high income settings.38 Although Abrysvo aligns well with existing maternal health care programs and provides infant protection for up to the first six months of life,37 there is currently limited evidence on its effectiveness beyond this period. Consideration is needed for infants requiring protection beyond the 6‐month point, such as those born prematurely or susceptible to infections after six months of age, highlighting the need for additional studies to address this gap. If infants are born prematurely, their mothers may not yet have received Abrysvo or transplacental transfer of maternal RSV antibodies may be insufficient and hence monoclonal antibodies (eg, nirsevimab) may be appropriate for these infants. Additionally, in the Northern Territory, 31% of children hospitalised with RSV‐related bronchiolitis were 6–24 months old39 and so these young children may benefit from a dose of nirsevimab in their second RSV season. As Abrysvo forms the foundation of Australia's national RSV immunisation program, analysing hospitalisation rates in infants beyond 6 months of age will be pivotal in assessing the vaccine's effectiveness over time. Since the current strategy primarily targets early infancy, outcomes in older infants will provide valuable data to identify any gaps in protection. This evidence will be crucial for refining the program and considering supplementary measures, such as monoclonal antibodies, to address potential vulnerabilities in populations at higher risk beyond the initial immunisation timeframe, noting that Australian jurisdictions have complementary RSV monoclonal antibody (nirsevimab) programs in 2025 for infants at increased risk.40,41,42,43

What else is in the pipeline?

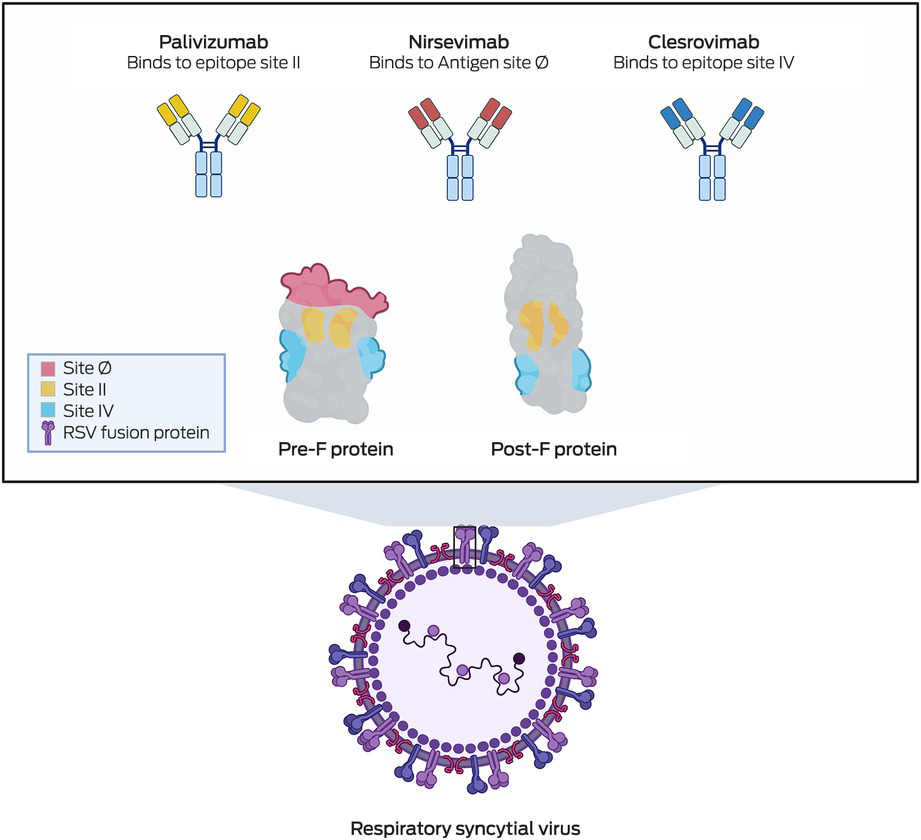

Clesrovimab (Merck), another form of RSV prophylaxis, is also a half‐life extended human monoclonal antibody targeting the pre‐F RSV glycoprotein. Phase 3 clinical trials have recently been completed,44 and show that among healthy preterm and full‐term infants (birth to 1 year of age), clesrovimab reduced the incidence of RSV‐associated medically attended lower respiratory infections by 60.4% compared with a placebo.44 Additionally, clesrovimab lowered RSV‐related hospitalisations by 84.2% and severe RSV cases by 91.7%,44 highlighting its potential in preventing severe RSV infections in infants. Box 3 shows the various epitopes on the RSV pre‐F protein that palivizumab, nirsevimab and clesrovimab each bind to — sites II, Ø and IV, respectively. This variation in binding sites could become clinically relevant in time, particularly if escape mutants develop resistance to one of the antibodies. Additionally, clesrovimab has demonstrated increased availability in extravascular compartments compared with nirsevimab,45 a characteristic that may enhance its efficacy in preventing RSV infections.

What is the current state of play in Australia?

In 2024, nirsevimab was available to infants and children only through funded, state‐managed programs in Western Australia, Queensland and New South Wales.46 Preliminary impact assessments from the 2024 RSV nirsevimab immunisation programs in Western Australia and Queensland have shown encouraging outcomes. In Western Australia, where approximately 71% of eligible infants under one year of age received nirsevimab prior to or during the RSV season, RSV‐related hospital admissions were 57% lower than forecast predictions, corresponding to 505 fewer hospitalisations16. In Queensland, RSV‐related hospitalisations among infants under six months of age decreased by 69% compared to the previous year, equating to one fewer hospitalisation per day in the early months of rollout, with projections suggesting that this figure could rise to three hospitalisations prevented per day by the end of the year.17

The economic burden of RSV is a crucial consideration when developing RSV immunoprophylaxis programs. In Australia each year, the mean per child aged under five years cost attributable to a hospital admission due to RSV disease is in excess of AUD$17 120 (2018–19),47 based on data from the Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne. As a quaternary paediatric centre, this figure reflects the elevated expenses associated with intensive care unit admissions and advanced care. However, this was a single‐centre study conducted seven years ago, highlighting the need for updated and broader cost evaluations across diverse health care settings. Additional data, including results from ongoing studies, are essential to better inform cost‐effectiveness analyses for RSV prevention products. While the cost per hospitalisation may remain consistent, reducing RSV‐related hospitalisations could extensively alleviate the overall financial burden on the health care system. Until now, the cost of a routine RSV preventive program would have been prohibitive, with the average cost of a course (five doses) of palivizumab for the RSV season being AUD$9 323 (2020),48 a financial burden which has proven to be a key constraint to its widespread use. Currently, in the USA, the private sector cost for nirsevimab is USD$519.75 (~AUD$827; exchange rate from January 2025 [USD$1 = AUD$1.59]) per dose for both 50 mg and 100 mg doses,49 while in European countries, the mean price was estimated at €339 (~AUD$567).50 In comparison, the private sector cost of Abrysvo in the USA is USD$295 (~AUD$469) per dose, representing a potentially more cost‐effective strategy for broad population‐level protection.

Abrysvo offers a more practical alternative to palivizumab and is available on the Australian private market at $331.99 per dose.50 Nirsevimab, while also included in the national strategy, is not currently available for private purchase and is distributed exclusively through government‐funded programs. The inclusion of Abrysvo in the NIP highlights the critical role of public funding in ensuring equitable and sustainable access to RSV prevention.

In 2025, all Australian jurisdictions have an RSV Mother and Infant Protection Program (MIPP), with the maternal RSV vaccine funded under the NIP commencing on 3 February 202551 and complementary monoclonal antibody (nirsevimab) programs funded by individual Australian state and territory governments. The program aims to reduce RSV‐related morbidity through the administration of a single dose of Abrysvo between 28 and 36 weeks’ gestation, thereby providing protection for infants against RSV. In addition to this, eligible infants, including infants born to mothers who did not receive Abrysvo during pregnancy or those with high risk conditions, will have access to the long‐acting monoclonal antibody nirsevimab at no cost, ensuring equitable protection for all infants at risk of RSV disease. Program monitoring and evaluation, including cost‐effectiveness modelling, from the 2025 RSV MIPPs will help guide future decisions regarding the optimal combination of maternal vaccination and nirsevimab. These studies, which will incorporate Australian‐specific data, will evaluate factors such as cost‐effectiveness, timing, geographic variability and logistical considerations in relation to administration. Although formal study announcements are still pending, these efforts are likely to form part of broader national evaluations accompanying RSV immunisation implementation. Surveillance activities, such as those captured by FluCAN and other systems listed by the Australian Centre for Disease Control,52 are also contributing to ongoing RSV monitoring and may inform these assessments.

An evidence‐based approach will be essential to ensure appropriate allocation of resources, tailoring programs to the specific needs of higher risk populations while maximising the economic and health benefits across Australia.

In addition to preventing severe RSV infections, it is also important to consider how RSV immunoprophylaxis programs may reduce recurrent wheeze and asthma following RSV infections in children. A comprehensive birth cohort study conducted in South Africa revealed that hospitalisation due to RSV infection was associated with a higher prevalence of recurrent wheeze compared with milder cases of RSV managed in the community.53 Although the observed adverse effects on lung function may be a consequence of RSV‐related LRTIs, it is also plausible that these effects reflect an underlying predisposition to both symptomatic RSV infection and long term respiratory conditions, such as asthma. However, recurrent LRTIs were also significantly more prevalent following an initial RSV infection,53 underscoring the potential long term impact of RSV on respiratory health during early childhood. Another recent study published by Rosas‐Salazar and colleagues demonstrated in a birth cohort of more than 1700 children that avoiding RSV infection during infancy could prevent up to 15% of childhood asthma cases.54 Well designed longitudinal studies to determine how early RSV prevention impacts future lung function and risk of asthma are needed.

To ensure the success of future RSV preventive programs in Australia, the timing, geographical variation and associated logistics of service delivery must also be considered. Since July 2021, RSV has been classified as a notifiable disease under the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System,2 offering crucial data on the temporal and geographical variations in RSV infections across Australia. In light of the national program, the timing of maternal RSV immunisation (administered between 28 and 36 weeks gestation) and the accurate recording of this information in the Australian Immunisation Register (AIR) will be crucial for monitoring vaccine uptake and ensuring continuity of care. As the service delivery for the maternal vaccine and infant monoclonal antibody may be managed by different health care providers, it is essential to capture this information on the AIR to enable comprehensive tracking of immunisation receipt across both strategies. Integrating data from both the maternal vaccine and nirsevimab, has already been initiated by participating states in 2024, but will require ongoing monitoring in future years to ensure immunisations are recorded and to optimise program effectiveness and assess long term respiratory outcomes.

Another important consideration is parental acceptance towards the new RSV preventives. A 2024 national survey that included both future and current parents of children aged under 5 years in Australia assessed current attitudes towards future RSV prevention strategies. Among the 1992 participants, 93.4% of future and 81.4% of current parents exhibited a high level of acceptance towards infant RSV immunisation before receiving information on RSV.55 Similarly, 79.7% of pregnant or planning parents and 86.9% of future parents (no other children) were willing to receive a maternal RSV vaccine during pregnancy.55 Although a 2019 study in Melbourne56 found that only 17% of pregnant women had heard of RSV, almost half (48%) of the participants were born outside Australia, highlighting the need for broad multi‐language programs to explain the risks and benefits of RSV prevention strategies. Reassuringly, both studies55,56 underscored the importance of education, as parents who were initially unaware of RSV demonstrated increased acceptance towards RSV preventives after being provided with relevant information. Understanding consumer decision making will be critical for policy makers and health care providers, particularly as the maternal vaccine landscape has three vaccines (influenza, pertussis and coronavirus disease 2019) currently recommended and included on NIP during pregnancy.

It is vital to prioritise the health of First Nations communities, who are disproportionately affected by severe RSV infections. In Central Australia, where First Nations Australians represent more than 41.8% of the population,57 the annual incidence of RSV infection in hospitalised children was found to be 29.6 per 1000 in First Nations children under the age of 2 years. This is nearly three times the 10.9 per 1000 incidence of their non‐First Nations counterparts.58 However, these figures may underestimate the true burden of RSV in First Nations communities. A WA study that developed a prediction model to estimate the burden of RSV in hospitalised children showed that laboratory‐confirmed RSV cases were likely underestimated, particularly among infants aged under 3 months. Children in this age group accounted for 22.4% of those tested but one in three RSV‐positive admissions and were found to have significantly higher odds of RSV positivity compared to older children. Notably, higher hospitalisation rates were observed among children from rural and remote regions, highlighting the increased susceptibility to RSV infection of rural and remote‐dwelling children.59 It is therefore essential to prioritise distribution of RSV preventives to these populations.

Conclusion

The landscape of RSV prevention in Australia rapidly evolved in 2024 with the introduction of two new prophylactic measures to protect infants: immunisation with long‐acting monoclonal antibody nirsevimab and maternal RSV vaccine Abrysvo. Maternal vaccination offers the advantage of protecting infants from birth through the passive transfer of antibodies, while nirsevimab provides direct and extended protection of infants during times of peak RSV activity.

Cost‐effectiveness remains a pivotal consideration in the implementation of national RSV preventive program in Australia. Both nirsevimab and Abrysvo have demonstrated substantial potential in reducing hospitalisation rates and mitigating long term health care costs associated with RSV infections in infants. Future pricing strategies, informed by ongoing research and real‐world efficacy data, will be critical to ensure the sustainability of both preventives for a broader population.

The 2025 federal and complementary jurisdictional programs for RSV prevention underscore a commitment to addressing the burden of RSV. Successful implementation will hinge on the timing and location of administration, addressing uptake and acceptance and ensuring accessibility to special risk groups including First Nations communities and other groups at increased risk. Continued surveillance, monitoring and evaluation will be essential to monitor the impact of these important interventions and adjust future RSV prevention strategies as indicated.

There is also an ongoing need to protect other age groups for which there are no preventives currently available. These include children older than 8 months (or 2 years for high‐risk) and young adults. The recent halting of clinical trials using mRNA vaccines in infants due to a potential safety signal highlights the ongoing challenges in RSV vaccine development in children.60

Box 1 – Effectiveness of nirsevimab in reducing hospital and paediatric intensive care unit admissions

|

Study details (lead author, country, study period) |

Inclusion criteria |

Nirsevimab coverage |

Effectiveness in reducing admissions |

Safety profile |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Effectiveness in reducing hospital admissions |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Ernst and colleagues23; Luxembourg; Sept to Dec 2023 |

|

84%; (1277 doses for 1524 infants) |

RSV‐related LRTI hospitalisations decreased by 69% for infants under 6 months old compared with the same period in 2022 (September 2022 to December 2022) |

No adverse events associated with the immunisation were reported |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Ares‐Gómez S and colleagues24; Spain; Oct 2023 to Jan 2024 |

|

92%; (9408 doses for 10 259 infants) |

RSV‐related LRTI hospitalisations were reduced by 89.8% in the first 3 months of the 2023–24 RSV season compared with the previous five RSV seasons (2016–17, 2017–18, 2018–19, 2019–20 and 2022–23) |

Five adverse events were reported, with three categorised as severe. None of the adverse events were considered to be related to nirsevimab |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Effectiveness in reducing intensive care unit admission |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Paireau J and colleagues26; France; Sept 2023 to Jan 2024 (case‐control study; test‐negative design) |

|

Over the study period, 58 infants (20%) had received nirsevimab 8 days or more before PICU admission |

After adjusting for age, sex, comorbidities, prematurity and time period (high v low RSV circulation), nirsevimab was between 75.9% and 80.6% effective in preventing severe RSV bronchiolitis in infants requiring PICU admission |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

LRTI = lower respiratory tract infections; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; PICU = paediatric intensive care unit; RSV = respiratory syncytial virus. |

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Sam T Barnett1

- Jane Tuckerman2,3

- Ian G Barr4,5

- Nigel W Crawford3,2

- Danielle F Wurzel2,3

- 1 Monash University, Melbourne, VIC

- 2 University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

- 3 Murdoch Children's Research Institute and The Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne, VIC

- 4 WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza, Melbourne, VIC

- 5 The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Melbourne, as part of the Wiley – The University of Melbourne agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Jane Tuckerman and Danielle Wurzel are named on an investigator‐led project grant sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Danielle Wurzel has received consultancy fees from Merck Sharp and Dohme and Praxhub, which have been directed to a research fund. Nigel Crawford is the Chair of the Australian Therapeutic Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI), where he provides evidence‐based health advice to government on vaccines and immunisation science, to guide public health policy, procedures and clinical use of the vaccines. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

- 1. Li Y, Wang X, Blau DM, et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022; 399: 2047‐2064.

- 2. National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System. National communicable disease surveillance dashboard. Department of Health and Aged Care, 2022. https://nindss.health.gov.au/pbi‐dashboard/ (viewed May 2024).

- 3. Anderson J, Oeum M, Verkolf E, et al. Factors associated with severe respiratory syncytial virus disease in hospitalised children: a retrospective analysis. Arch Dis Child 2022; 107: 359‐364.

- 4. Saravanos GL, Sheel M, Homaira N, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus‐associated hospitalisations in Australia, 2006‐2015. Med J Aust 2019; 210: 447‐453. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2019/210/10/respiratory‐syncytial‐virus‐associated‐hospitalisations‐australia‐2006‐2015

- 5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's children (cat. no. CWS 69). Canberra: AIHW, 2020.

- 6. Chang AB, Bell SC, Torzillo PJ, et al. Chronic suppurative lung disease and bronchiectasis in children and adults in Australia and New Zealand. Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand guidelines. Med J Aust 2015; 202: 21‐23. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2015/202/1/chronic‐suppurative‐lung‐disease‐and‐bronchiectasis‐children‐and‐adults

- 7. Chang AB, Grimwood K, Mulholland EK, et al. Bronchiectasis in Indigenous children in remote Australian communities. Med J Aust 2002; 177: 200‐204. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2002/177/4/bronchiectasis‐indigenous‐children‐remote‐australian‐communities

- 8. Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). In: Australian Immunisation Handbook, Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, Canberra, 2022. https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/contents/vaccine‐preventable‐diseases/respiratory‐syncytial‐virus‐rsv#:~:text=Palivizumab%20is%20recommended%20for%20infants,start%20of%20the%20RSV%20season (viewed Jan 2025).

- 9. South Australian Medicines Evaluation Panel. Palivizumab for prevention of serious lower respiratory tract disease caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in infants at high risk of RSV disease. Government of South Australia, October 2015.

- 10. Xu R, Fathima P, Strunk T, et al. RSV prophylaxis use in high‐risk infants in Western Australia, 2002‐2013: a record linkage cohort study. BMC Pediatr 2020; 20: 490.

- 11. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian prescription medicine decision summaries: Beyfortus, December 2023. https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/auspmd/beyfortus (viewed June 2024).

- 12. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian prescription medicine decision summaries: ABRYSVO recombinant respiratory syncytial virus pre‐fusion F protein 120 microgram/0.5 mL bivalent vaccine powder for injection vial + diluent syringe (406624). March 2024. https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/artg/406624 (viewed May 2024).

- 13. Western Australia Department of Health. 2024 RSV Infant Immunisation Program. Perth: Western Australia Department of Health, March 2024. https://www.health.wa.gov.au/News/2024/2024‐RSV‐Infant‐Immunisation‐Program (viewed Apr 2025).

- 14. Queensland Government. Free RSV immunisation for Queensland newborns. Brisbane: Queensland Government, March 2024. https://www.qld.gov.au/about/newsroom/free‐rsv‐immunisation‐for‐queensland‐newborns#:~:text=From%2015%20April%202024%2C%20newborn,Islander%20infants%20under%208%20months (viewed Apr 2025).

- 15. New South Wales Health. NSW RSV Prevention Program – Frequently Asked Questions for Health Professionals. May 2024. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/immunisation/Pages/nirsevimab‐professionals.aspx. (viewed May 2024).

- 16. Bloomfield LE, Pingault NV, Foong RE, et al. Nirsevimab immunisation of infants and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)‐associated hospitalisations, Western Australia, 2024: a population‐based analysis. Med J Aust 2025; 222. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.52655.

- 17. Ferguson G, Clarke S. Number of Queensland babies hospitalised with respiratory illness down 70pc since RSV jab released. ABC News. 16 April 2025. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025‐04‐16/qld‐rsv‐vaccine‐influenza‐shot‐flu‐season‐immunity‐illness/105182216 (viewed Apr 2025).

- 18. Australian Government Department of Health. Neonates and infants aged <8 months whose mothers were not vaccinated at least 2 weeks before delivery, or who are at increased risk of severe disease, are recommended to receive passive immunisation with an RSV‐specific monoclonal antibody. January 2025. https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/recommendations/neonates‐and‐infants‐aged (viewed Apr 2025).

- 19. The IMpact‐RSV Study Group. Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus infection in high‐risk infants. Pediatrics 1998; 102: 531‐537.

- 20. Kuitunen I, Backman K, Gärdström E, Renko M. Monoclonal antibody therapies in respiratory syncytial virus prophylaxis—an umbrella review. Pediatr Pulmonol 2024; 59, 2374‐2380.

- 21. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). In: Immunisation Handbook. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, 2024. https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/contents/vaccine‐preventable‐diseases/respiratory‐syncytial‐virus‐rsv (viewed Aug 2024).

- 22. Zar HJ, Piccolis M, Terstappen J, et al. Access to highly effective long‐acting RSV‐monoclonal antibodies for children in LMICs‐reducing global inequity. Lancet Glob Health 2024; 12: e1582‐e1583.

- 23. Ernst C, Bejko D, Gaasch L, et al. Impact of nirsevimab prophylaxis on paediatric respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)‐related hospitalisations during the initial 2023/24 season in Luxembourg. Euro Surveill 2024; 29: 2400033.

- 24. Ares‐Gómez S, Mallah N, Santiago‐Pérez MI, et al. Effectiveness and impact of universal prophylaxis with nirsevimab in infants against hospitalisation for respiratory syncytial virus in Galicia, Spain: initial results of a population‐based longitudinal study. Lancet Infect Dis 2024; 24: 817‐828.

- 25. Paireau J, Durand C, Raimbault S, et al. Nirsevimab effectiveness against cases of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis hospitalised in paediatric intensive care units in France, September 2023‐January 2024. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2024; 18: e13311.

- 26. Levy C, Werner A, Rybak A, et al. Early impact of nirsevimab on ambulatory all‐cause bronchiolitis: a prospective multicentric surveillance study in France. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2024; 13: 371‐373.

- 27. Riccò M, Cascio A, Corrado S, et al. Impact of nirsevimab immunization on pediatric hospitalization rates: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Vaccines (Basel) 2024; 12: 640.

- 28. Oluwaseun S, Cagnan L, Xausa I, et al. Projected public health impact of a universal rotavirus vaccination program in France. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2024; 43: 902‐908.

- 29. Dey A, Wang H, Menzies R, Macartney K. Changes in hospitalisations for acute gastroenteritis in Australia after the national rotavirus vaccination program. Med J Aust 2012, 197, 453‐457. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2012/197/8/changes‐hospitalisations‐acute‐gastroenteritis‐australia‐after‐national

- 30. Consolati A, Farinelli M, Serravalle P, et al. Safety and efficacy of nirsevimab in a universal prevention program of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in newborns and infants in the first year of life in the Valle d’Aosta region, Italy, in the 2023–2024 epidemic season. Vaccines (Basel) 2024; 12: 549.

- 31. Dagan R, Hammitt LL, Seoane Nuñez B, et al. Infants receiving a single dose of nirsevimab to prevent RSV do not have evidence of enhanced disease in their second RSV season. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2024; 13: 144‐147.

- 32. Wilkins D, Yuan Y, Chang Y, et al. Durability of neutralizing RSV antibodies following nirsevimab administration and elicitation of the natural immune response to RSV infection in infants. Nat Med 2023; 29: 1172‐1179.

- 33. Ahani B, Tuffy KM, Aksyuk AA, et al. Molecular and phenotypic characteristics of RSV infections in infants during two nirsevimab randomized clinical trials. Nat Commun 2023; 14: 4347.

- 34. Wilkins D, Langedijk AC, Lebbink RJ, et al. Nirsevimab binding‐site conservation in respiratory syncytial virus fusion glycoprotein worldwide between 1956 and 2021: an analysis of observational study sequencing data. Lancet Infect Dis 2023; 23: 856‐866.

- 35. Wang X, Li Y, Nair H, Campbell H, RESCEU Investigators. Time‐varying association between severe respiratory syncytial virus infections and subsequent severe asthma and wheeze and influences of age at the infection. J Infect Dis 2022; 226(Suppl 1): S38–44.

- 36. Sanz‐Muñoz I, Castrodeza‐Sanz J, Eiros JM. Potential effects on elderly people from nirsevimab use in infants. Open Respir Arch 2024; 6: 100320.

- 37. Kampmann B, Madhi SA, Munjal I, et al. Bivalent prefusion F vaccine in pregnancy to prevent RSV illness in infants. N Engl J Med 2023; 388: 1451‐1464.

- 38. World Health Organization. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2024; 99: 325‐336.

- 39. McCallum GB, Grimwood K, Oguoma VM, et al. The point prevalence of respiratory syncytial virus in hospital and community‐based studies in children from Northern Australia: studies in a ‘high‐risk’ population. Rural Remote Health 2019; 19: 5267.

- 40. Victorian Government. Respiratory syncytial virus immunisation [website]. Melbourne: Victorian Government, Jan 2025. https://www.health.vic.gov.au/immunisation/respiratory‐syncytial‐virus‐immunisation (viewed Jan 2025).

- 41. NSW Health. Respiratory syncytial virus, January 2025. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/immunisation/Pages/respiratory‐syncytial‐virus.aspx (viewed Jan 2025).

- 42. Queensland Health. Queensland paediatric respiratory syncytial virus prevention program [website]. Brisbane: Queensland Health, 2025. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/clinical‐practice/guidelines‐procedures/diseases‐infection/immunisation/paediatric‐rsv‐prevention‐program (viewed Jan 2025).

- 43. South Australian Government. Protecting babies against potentially deadly RSV [website]. Adelaide: Government of South Australia, 2025. https://www.premier.sa.gov.au/media‐releases/news‐items/protecting‐babies‐against‐potentially‐deadly‐rsv (viewed Jan 2025).

- 44. Zar HJ, Simoes E, Madhi S, et al. 166. A phase 2b/3 study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of an investigational respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) antibody, Clesrovimab, in healthy preterm and full‐term infants. Open Forum Infect Dis 2025;12(Suppl 1):ofae631.003.

- 45. Phuah JY, Maas BM, Tang A, et al. Quantification of clesrovimab, an investigational, half‐life extended, anti‐respiratory syncytial virus protein F human monoclonal antibody in the nasal epithelial lining fluid of healthy adults. Biomed Pharmacother 2023; 169: 115851.

- 46. AusVaxSafety. Nirsevimab vaccine safety data. Sydney: AusVaxSafety, 2024. https://ausvaxsafety.org.au/vaccine‐safety‐data/nirsevimab (viewed Jan 2025).

- 47. Brusco NK, Alafaci A, Tuckerman J, et al. The 2018 annual cost burden for children under five years of age hospitalised with respiratory syncytial virus in Australia. Commun Dis Intell (2018) 2022; 46: https://doi.org/10.33321/cdi.2022.46.5.

- 48. Royal Hospital for Women. Palivizumab. Sydney: South Eastern Sydney Local Health District, 2020. https://www.seslhd.health.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/groups/Royal_Hospital_for_Women/Neonatal/Neomed/neomed20palivizumabfull.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 49. American Academy of Pediatrics. Nirsevimab (Beyfortus) product & ordering information [website]. AAP, 2024. https://www.aap.org/en/patient‐care/respiratory‐syncytial‐virus‐rsv‐prevention/nirsevimab‐beyfortus‐product‐‐ordering‐information/#:~:text=Nirsevimab%20purchase%20cost,for%2050mg%20and%20100mg%20doses (viewed May 2024).

- 50. Chemist Warehouse. Abrysvo Vaccine 120 microgram/0.5 mL syringe and diluent – RSV Vaccine. Chemist Warehouse: 2025. https://www.chemistwarehouse.com.au/buy/143334/abrysvo‐vaccine‐120‐microgram‐0‐5‐ml‐syringe‐and‐diluent‐1‐rsv‐vaccine (viewed Apr 2025).

- 51. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Minister for Health and Aged Care Press Conference 19 January 2025. https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the‐hon‐mark‐butler‐mp/media/minister‐for‐health‐and‐aged‐care‐press‐conference‐19‐january‐2025 (viewed Jan 2025).

- 52. Australian Centre for Disease Control. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Department of Health and Aged Care. 2025. https://www.cdc.gov.au/topics/respiratory‐syncytial‐virus‐rsv (viewed Apr 2025).

- 53. Zar HJ, Nduru P, Stadler JAM, et al. Early‐life respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infection in a South African birth cohort: epidemiology and effect on lung health. Lancet Glob Health 2020; 8: e1316‐e1325.

- 54. Rosas‐Salazar C, Chirkova T, Gebretsadik T, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection during infancy and asthma during childhood in the USA (INSPIRE): a population‐based, prospective birth cohort study. Lancet 2023; 401: 1669‐1680.

- 55. Holland C, Baker M, Bates A, et al. Parental awareness and attitudes towards prevention of respiratory syncytial virus in infants and young children in Australia. Acta Paediatr 2024; 113: 786‐794.

- 56. Giles ML, Buttery J, Davey MA, Wallace E. Pregnant women's knowledge and attitude to maternal vaccination including group B streptococcus and respiratory syncytial virus vaccines. Vaccine 2019; 37: 6743‐6749.

- 57. De Vincentiis B, Guthridge S, Su J‐Y, Johnston K. Story of our children and young people, Central Australia 2021. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research, 2021.

- 58. Dede A, Isaacs D, Torzillo PJ, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infections in Central Australia. J Paediatr Child Health 2010; 46: 35‐39.

- 59. Gebremedhin AT, Hogan AB, Blyth CC, et al. Developing a prediction model to estimate the true burden of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in hospitalised children in Western Australia. Sci Rep 2022; 12: 332.

- 60. Cohen J. Safety signal in Moderna's RSV vaccine studies halts trials of other vaccines in childhood. Science, 13 Dec 2024. https://www.science.org/content/article/safety‐signal‐moderna‐s‐rsv‐vaccine‐studies‐halts‐trials‐other‐vaccines‐childhood (viewed Feb 2025).

Summary