Community-based “participatory research” (PR) is desirable because it fosters partnerships between a community and research agencies, enabling inclusivity, interdependence and democratic knowledge production to reduce health inequalities.1-4 Support for PR is particularly strong when research involves indigenous peoples5,6 as it promotes self-determination, creating more transparent and equitable conditions for knowledge creation and benefit sharing.3,7 PR as a methodology may range from being consultative5 through community-directed8 to community-controlled, where community groups exercise the highest expression of autonomy over research, assisted by research institutions.9

In Australia, one Aboriginal human research ethics committee (HREC) will only approve a research project when “there is Aboriginal community control over all aspects of the proposed research”, including design, data ownership, interpretation and publication.10 Other approval criteria include the betterment of Aboriginal peoples' health, cultural sensitivity and a capacity to benefit. These are hallmarks of PR, and there are now World Health Organization guiding principles specific to indigenous peoples,7 along with guidelines,11,12 joint statements,13-15 and a systematic review,1 to influence PR design and complement guidelines for ethical research involving Indigenous Australians.16 The WHO principles for PR reflect experience in various countries and provide guidance on the joint management of research by research institutions and indigenous peoples. These principles are described as being “applicable everywhere and to all fields of research involving Indigenous Peoples”.7

In this supplement, we report on the Talking About The Smokes (TATS) project, a large-scale PR collaboration between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, their representative bodies, and researchers. This national research project was initiated in 2010 to examine pathways to quitting smoking and the impact of tobacco control policies in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population. The TATS project is one of many studies within the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project (ITC Project) to follow nationally representative cohorts of smokers, to measure psychosocial and behavioural impacts of tobacco control policies.17 However, it is the first to sample only a high-prevalence subpopulation within a country.18

In this article, we describe the TATS project PR methodology according to the WHO guiding principles, to assist others planning large-scale PR projects.

Background

In 2012–2013, 42% of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population aged 15 years or older were daily smokers — 2.6 times the age-standardised prevalence among other Australians.19 Australian governments aimed to halve the Indigenous Australian smoking rate by 2018 (from the 2009 baseline) through a range of Indigenous tobacco control initiatives.20 Funded by the Australian Government in support of these national initiatives, the TATS project was conducted mainly through Aboriginal community-controlled health services (ACCHSs).

ACCHSs provide comprehensive primary health care services to more than 310 000 people (2010–11), with nearly 80% identifying as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. The 150 ACCHSs located across Australia are almost entirely Aboriginal-controlled, with a governance structure comprising elected members of the Aboriginal community.21 Although funded largely by the Australian Government,21 they are independent not-for-profit agencies, established by Aboriginal leaders from 1971 in response to significant unmet health needs.22 ACCHSs were involved in the TATS project partly because those most affected by the research outcomes were likely to be patients and staff of these services, but also because of the representativeness of ACCHSs at the local community level, which enabled community control over the research process at each site.

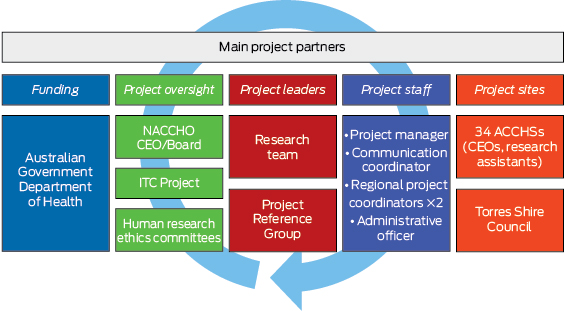

The TATS project was led by the Menzies School of Health Research (Menzies) in a formal partnership with the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO). The research team included researchers from Menzies, the Centre for Excellence in Indigenous Tobacco Control, Cancer Council Victoria, two state affiliate organisations of NACCHO (Affiliates) — the Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council (QAIHC) and the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales (AH&MRC) — and researchers representing NACCHO. The researcher from Cancer Council Victoria is an investigator on other ITC Project surveys. Project support staff were employed at Menzies and NACCHO, and at 34 local ACCHSs as research assistants (Box 1).

The project used two waves of survey data in 35 locations (the 34 ACCHSs and a community in the Torres Strait). In the first of these waves, 2522 community members and 645 ACCHS staff were surveyed from April 2012 to October 2013. The research methods and baseline sample are described elsewhere.18

Methods

The WHO guiding principles were adapted from their narrative form into a reporting framework in which the text (verbatim) was rearranged into seven themes with numbered subsections (Appendix 1). A condensed version of the framework is shown in Box 2. This framework was used to assess the PR process in the TATS project. Anticipated and unanticipated benefits of the project were sourced from the research protocol, ethics submissions and anecdotal reports from ACCHSs.

Throughout this report, links to the numbered subsections of the framework are shown in parentheses. The framework and the WHO principles refer to indigenous peoples as those “with clearly identifiable community and leadership structures … and a significant political voice”.7 Our references to Indigenous peoples include Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders and their representative bodies, such as NACCHO, ACCHSs and Affiliates — all independent but related entities.

Permission to use the framework was provided by the lead author of the WHO principles (Harriet Kuhnlein, Founding Director, Centre for Indigenous Peoples' Nutrition and Environment, Quebec, Canada, personal communication, February 2014).

Results

The PR approach adopted by the TATS project is described using the seven themes from the adapted framework (Box 2).

1. Consultation and approval

The TATS project was initiated as a result of conversations between three researchers (from Menzies, Cancer Council Victoria and the Centre for Excellence in Indigenous Tobacco Control), one of whom is Aboriginal, and was influenced by the usefulness of ITC Project surveys in other settings. A decision was made to invite Aboriginal organisations as partners. Initial contact with these organisations was made at a meeting of all Affiliates, after which two researchers (from QAIHC and AH&MRC) agreed to participate. In view of the national significance of the proposed research and synergies with national tobacco control policy and community priorities, NACCHO proposed a partnership with Menzies, which was accepted, and NACCHO representatives joined the research team (1.1–1.5).

2. Partnerships and research agreements

Several types of research agreements, some legally binding, were made between the partners (Box 3). The earliest agreement comprised a memorandum of understanding (MOU) initiated by NACCHO to guide the shared development of the research protocol and funding proposal with Menzies, and to ensure consistency with the research and policy priorities of both institutions (2.1). Other agreements comprised two funding contracts between Menzies and the Australian Government and a subcontract with NACCHO, the research protocol, site agreements and consent forms.

Other research team members chose not to make legal agreements between their employers and Menzies; their involvement was sustained by common interests and a history of existing relationships between individuals. Researchers from QAIHC and AH&MRC received endorsement from the Aboriginal leadership of these bodies to participate as individuals in the project.

The research team collaboratively developed the research protocol, with review by the Project Reference Group (PRG), and this was endorsed by the NACCHO Board 18 months after the MOU was signed. The protocol articulated the roles and responsibilities of all partners, the agreed conditions and all steps of the research process (2.2–2.6). Menzies was the administering agency and project manager, and NACCHO acted as advisor for responsible research conduct, communication and coordination involving ACCHSs, in collaboration with other research team members.

Local ACCHSs were informed about the TATS project and the NACCHO–Menzies research partnership and invited to express an interest in participation, pending funding. Although ACCHSs had minimal involvement in the development of the research protocol, it formed the basis of the individually negotiated site consent forms and site agreements (Box 3). All parties to these agreements committed to the successful completion of the research, but could withdraw at any time with notice (2.7–2.8).

3. Communication

Lines of authority within participating Aboriginal organisations were respected; the project staff communicated with managers, chief executive officers and boards where appropriate (Box 1). The key to coordination was the employment of project staff to facilitate engagement between the research team and sites using existing ACCHS sector networks, communication between Menzies and NACCHO, and reporting to the NACCHO Board (3.1).

The NACCHO Board approved the structure, role and membership of the research team and the PRG. Appointments to the PRG were facilitated by NACCHO and comprised Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders from all Affiliates and a member of the NACCHO Board as Chair. This ensured the PRG could represent ACCHSs from all jurisdictions. The PRG provided advice, monitored the ethical conduct of research, and assisted in prioritising data analysis (3.2). Members of the PRG were also involved in the interpretation of results, increasing the involvement of Indigenous peoples in this part of the research process.

Communication responsibilities were articulated in the research protocol, funding agreements and site agreements, and included the release of progress reports and a national knowledge exchange forum involving all sites (3.3–3.4).

4. Funding

The initiating three researchers procured establishment funding to negotiate and make agreements with key stakeholders and develop the research protocol and instruments. Thereafter, all research team members had oversight of project fund seeking, as the establishment of partnerships preceded the acquisition of these funds (4.1).

To assure mutual interests, primary contract negotiations involving Menzies and the funder were synchronously aligned with the development of the subcontract with NACCHO. All site agreements were also contracted with Menzies, which funded ACCHSs to undertake local surveys by employing research assistants (4.2) (Box 3).

5. Ethics and consent

Approval from three Aboriginal HRECs and two other HRECs with Aboriginal subcommittees was secured across four jurisdictions before finalisation of the research protocol and signing of the funding contract with NACCHO (5.2–5.3). The MOU, ethics applications and research protocol committed the parties to adhere to ethics guidelines16 and conform to NACCHO data protocols.23 These protocols were developed and endorsed by the ACCHS sector to affirm the importance of Aboriginal peoples and their representative bodies acting as owners and custodians of their own data (5.1, 5.4, 5.7).

Three levels of consent were sought and obtained: Aboriginal collective consent at the national level through NACCHO;24 local community collective consent from each individual ACCHS and the Torres Shire Council (representing the Torres Strait community, as there is not a local ACCHS); and informed consent procured from individual survey participants by research assistants (5.5) (Box 2).

Research assistants had some control over how data would be collected in their community, thereby accommodating cultural and geographic diversity across sites. The consent of study participants was obtained in writing using consent forms approved by the research team as per ethics guidelines (5.6).16

6. Data

Primary contract negotiations stated that intellectual property rights to products arising from the project were vested in Menzies. Through subcontracting, NACCHO and individual ACCHSs were granted a perpetual licence to use, adapt and publish project outputs in accordance with the research protocol and, therefore, the NACCHO data protocols (6.1). The primary funding contract, NACCHO subcontract and research protocol stipulated that raw (unanalysed) data collected from ACCHSs remained the property of the specific ACCHSs “when considered both in isolation and at a national level”. Site agreements clarified that: the collected data were to be used by the research team only as outlined in the research protocol; release of information identifying ACCHSs required their review; and publication of aggregated national results required review by NACCHO (or Affiliates where jurisdictions were identified) (6.2).

Confidential information was protected using a password-protected database, with separate storage of a unique identifying code available only to approved staff and research team members (6.3). This code was necessary for the re-identification of participants in the follow-up survey a year after the baseline survey.

Research agreements ensured that data analyses and interpretations in publications and conference presentations were agreed on by the research team or through joint meetings with the PRG, and then reviewed by NACCHO before submission for publication (6.4). Authorship of manuscripts was negotiated based on international criteria,25 with capacity for Indigenous members of the research team, PRG or project staff, or Indigenous research assistants, to be authors (6.5). ACCHSs were also provided with summaries of their local data in clear language and in formats enabling their independent use (6.6).

ACCHSs' ownership of their unanalysed data meant that new research requests unrelated to the original agreement would require endorsement from the relevant ACCHS or, on national matters, the NACCHO Board and the PRG (6.7).

7. Benefits of the research

Anticipated research benefits were identified in all research agreements and other information provided to ACCHSs and participants (7.1) (Box 4). No commercial benefits were considered likely (7.2). The recruitment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to the PRG and the employment of three project staff at NACCHO and 101 local research assistants in ACCHSs helped build individual Indigenous and organisational capacity (7.3) (Box 4). All except seven of the research assistants were local Indigenous people. Funding was provided to ACCHSs for these appointments and to compensate survey participants (in the form of vouchers). Anecdotal benefits to survey participants and services were freely communicated (Box 5).

Discussion

The TATS project exemplifies community-directed research,8 where participation between partners is democratised. While the design of the TATS project was shaped by the institutional, policy and research experience of Aboriginal organisations, research agencies and individual researchers, it closely mirrored the WHO's PR principles. The TATS project involved 34 ACCHSs conducting baseline and follow-up surveys, making it one of the largest PR projects in Australia. We can affirm that large-scale PR involving vulnerable populations is achievable.

When communities and researchers seek solutions to the same health problems, negotiating this interdependence into a research partnership can help community researchers feel like they are “doing meaningful public health work, not just conducting research”.26 Ultimately, PR relies on forming the right partnerships.27 The relational ethics of the TATS project were negotiated through pre-existing trust between individuals from partner organisations and the individual relationships that developed during the project. They were also negotiated formally through research agreements that embedded community “ways of knowing” and Indigenous ownership over products such as research data.5 This meant that ACCHSs retained autonomy over their collected local information, including into the future — an outcome normally considered challenging.6 Establishing partnerships can take months, particularly where legal agreements are negotiated. Securing an establishment grant for TATS project preparatory work, as well as being transparent about funding uncertainty and research time frames, allowed time for partnerships to develop.

Through NACCHO, the project received the approval and involvement of the Aboriginal health leadership of the ACCHS sector nationwide. Research assistants recruited by ACCHSs from the local population enhanced trust and increased participant recruitment, as did the provision of financial compensation. These strategies are known to increase research response rates in minority populations.26,28,29 Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders were employed and involved in all aspects of the project, from conception and design to analysis and dissemination. While the WHO principles promote active Indigenous involvement, including self-determination over the degree of research involvement, advice on building Indigenous capacity through Indigenous employment and career development is more explicit in other guidelines.13,15

We did not attempt to quantify congruence of our project with PR principles,1,8 but the framework we adapted served to structure and focus our reporting “beyond the rhetoric”,5 illustrating applied PR principles in large-scale community-based research. Investment in a research process that is participatory, in both “methodology and method”, is rewarding and sometimes more important than the outcome.30 Participation can empower communities and is recognised as an outcome in itself.31 Community participation in research delivers social and cultural validity when inquiries are aligned with the needs and priorities of those being researched, and better external validity of findings for generalisability.3 Achieving this through PR may be more costly in the short term but in the long term builds health equity32 and facilitates translation of research into policy.3

PR is common but there is no single PR strategy, as self-determined community priorities are unique.4 Sharing our strategies may encourage others to adopt similar research models involving indigenous peoples for equitable knowledge creation, and to build stronger future partnerships.

2 Condensed framework: guiding principles for participatory health research involving research institutions, Indigenous peoples and their representative bodies*

Theme | Subsection | The guiding principles refer to: | |||||||||||||

1. Consultation and approval | 1.1–1.3 | Initiation of research and making contact | |||||||||||||

1.4–1.5 | Approval for the research to proceed | ||||||||||||||

2. Partnerships and research agreements | 2.1–2.4 | Equality of research relationships, joint preparation of a research agreement and research proposal | |||||||||||||

2.5–2.6 | Development of agreed research processes | ||||||||||||||

2.7–2.8 | Joint obligations towards the research | ||||||||||||||

3. Communication | 3.1 | Clarification of, and respect for, the lines of authority of the partners | |||||||||||||

3.2 | Committee selection by Indigenous peoples (for communication, facilitation and promotion); the committee should represent all relevant community-controlled organisations | ||||||||||||||

3.3–3.4 | Maintenance of communication, including progress reports, results and implications of the research | ||||||||||||||

4. Funding | 4.1–4.2 | A joint commitment to fund seeking, and agreement of sources in advance | |||||||||||||

4.3 | Research institutions' obligation to ensure Indigenous peoples are involved where resources or capacity are lacking | ||||||||||||||

5. Ethics and consent | 5.1–5.2 | Respect for ethical guidelines, approval from human research ethics committees and Indigenous-controlled ethics committees | |||||||||||||

5.3 | Research commencing only after ethics approval is received and signed agreements are finalised | ||||||||||||||

5.4 | Research conforming to additional protocols of the Indigenous peoples involved | ||||||||||||||

5.5 | Consent for research at various levels: individual (study participants), representatives of Indigenous peoples, and the umbrella Indigenous organisation | ||||||||||||||

5.6 | A jointly agreed consent-seeking process | ||||||||||||||

5.7 | Umbrella Indigenous organisation demonstrating the collective consent of Indigenous peoples | ||||||||||||||

6. Data | 6.1–6.2 | Intellectual property rights, benefit sharing and boundaries pertaining to information use | |||||||||||||

6.3 | Confidentiality and limiting access to research data | ||||||||||||||

6.4 | Joint review and interpretation of data before publication | ||||||||||||||

6.5 | Authorship or acknowledgement of participants in joint research | ||||||||||||||

6.6 | Formatting data and reports for independent use by Indigenous peoples | ||||||||||||||

6.7 | Indigenous ownership of data and authorisation for further use | ||||||||||||||

7. Benefits of the research | 7.1 | Obligation for research to provide short-term and long-term benefits for Indigenous peoples, including provision of health care where lacking | |||||||||||||

7.2 | Disclosure of potential economic benefits of the research | ||||||||||||||

7.3 | Research benefits including training, employment, general capacity building and improved health status or services (or prospects for such improvement) | ||||||||||||||

* Adapted from the World Health Organization, 2003.7 See Appendix 1 for the full framework. | |||||||||||||||

3 Types of research agreements used in the Talking About The Smokes (TATS) project

Research agreement | Function | Signatories | |||||||||||||

Memorandum of understanding | Commit parties to developing a research partnership | Menzies, NACCHO | |||||||||||||

Funding contracts | Fund both the establishment phase and the full TATS project | Menzies, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing | |||||||||||||

Subcontract | Fund NACCHO project staff to deliver TATS services | Menzies, NACCHO | |||||||||||||

Research protocol | Document the agreed research processes (goals, planning, design, methods, consent, data collection, analysis, interpretation, dissemination and reporting) | Research team members (and endorsed by NACCHO Board) | |||||||||||||

Site agreements | Articulate the terms of engagement including roles and responsibilities, and provide funding for employment of research assistants and purchase of consumables | Menzies, ACCHSs | |||||||||||||

Site consent forms | Document collective consent of the community served by the ACCHS | Menzies, ACCHSs | |||||||||||||

Survey consent forms | Document individual consent | Survey participants, research assistants | |||||||||||||

Menzies = Menzies School of Health Research. NACCHO = National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. ACCHS = Aboriginal community-controlled health service. | |||||||||||||||

4 Benefits of the Talking About The Smokes project

Benefits | Explanation | ||||||||||||||

To study participants |

| ||||||||||||||

To health services |

| ||||||||||||||

Towards employment |

| ||||||||||||||

Enhancing research capacity |

| ||||||||||||||

Towards partnerships |

| ||||||||||||||

Towards Indigenous participation |

| ||||||||||||||

Towards improved knowledge exchange |

| ||||||||||||||

ACCHS = Aboriginal community-controlled health service. NACCHO = National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. | |||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Sophia Couzos1

- Anna K Nicholson2

- Jennifer M Hunt3

- Maureen E Davey4

- Josephine K May5

- Pele T Bennet6

- Darren W Westphal2

- David P Thomas2

- 1 James Cook University, Townsville, QLD.

- 2 Menzies School of Health Research, Darwin, NT.

- 3 Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council, Sydney, NSW.

- 4 Aboriginal Health Service, Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, Hobart, TAS.

- 5 National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, Canberra, ACT.

- 6 Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council, Brisbane, QLD.

The full list of acknowledgements is available in Appendix 2.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, et al. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2004; (99): 1-8.

- 2. Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health 1998; 19: 173-202.

- 3. Cargo M, Mercer SL. The value and challenges of participatory research: strengthening its practice. Annu Rev Public Health 2008; 29: 325-350.

- 4. Israel BA, Eng E, Shultz AJ, Parker EA. Introduction to methods for CPBR for health. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Shultz AJ, Parker EA, editors. Methods for community-based participatory research for health. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2012: 3-38.

- 5. Kendall E, Sunderland N, Barnett L, et al. Beyond the rhetoric of participatory research in Indigenous communities: advances in Australia over the last decade. Qual Health Res 2011; 21: 1719-1728.

- 6. Cochran PA, Marshall CA, Garcia-Downing C, et al. Indigenous ways of knowing: implications for participatory research and community. Am J Public Health 2008; 98: 22-27.

- 7. World Health Organization. Indigenous peoples & participatory health research. Geneva: WHO, 2003. http://www.who.int/ethics/indigenous_peoples/en/index1.html (accessed Sep 2014).

- 8. Cargo M, Delormier T, Lévesque L, et al. Can the democratic ideal of participatory research be achieved? An inside look at an academic–indigenous community partnership. Health Educ Res 2008; 23: 904-914.

- 9. Couzos S, Lea T, Murray R, Culbong M. ‘We are not just participants — we are in charge': the NACCHO ear trial and the process for Aboriginal community-controlled health research. Ethn Health 2005; 10: 91-111.

- 10. Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council Ethics Committee. AH&MRC guidelines for research into Aboriginal health — key principles. Revision February 2013. http://www.ahmrc.org.au/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&gid=22&Itemid=45 (accessed Sep 2014).

- 11. First Nations Centre. OCAP: ownership, control, access and possession. Sanctioned by the First Nations Information Governance Committee, Assembly of First Nations. Ottawa: National Aboriginal Health Organization, 2007. http://cahr.uvic.ca/nearbc/documents/2009/FNC-OCAP.pdf (accessed Sep 2014).

- 12. Mercer SL, Green LW, Cargo M, et al. Appendix C: Reliability tested guidelines for assessing participatory research projects. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2008. http://lgreen.net/24AppendixC%20%20FINAL.doc (accessed Sep 2014).

- 13. Jamieson LM, Paradies YC, Eades S, et al. Ten principles relevant to health research among Indigenous Australian populations. Med J Aust 2012; 197: 16-18. <MJA full text>

- 14. Henderson R, Simmons DS, Bourke L, Muir J. Development of guidelines for non-Indigenous people undertaking research among the Indigenous population of north-east Victoria. Med J Aust 2002; 176: 482-485. <MJA full text>

- 15. South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute. Wardliparingga: Aboriginal research in Aboriginal hands. South Australian Aboriginal Health Research Accord: companion document. Adelaide: SAHMRI, 2014. https://www.sahmri.com/user_assets/2fb92e8c37ba5c16321e0f44ac799ed581adfa43/companion_document_accordfinal.pdf (accessed Sep 2014).

- 16. National Health and Medical Research Council. Values and ethics: guidelines for ethical conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2003. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines/publications/e52 (accessed Sep 2014).

- 17. International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project [website]. http://www.itcproject.org (accessed Sep 2014).

- 18. Thomas DP, Briggs VL, Couzos, S, et al. Research methods of Talking About The Smokes: an International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project study with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Med J Aust 2015; 202 (10 Suppl): S5-S12. <MJA full text>

- 19. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: updated results, 2012–13. Canberra: ABS, 2014. (ABS Cat. No. 4727.0.55.006.)

- 20. Council of Australian Governments Reform Council. Healthcare 2010–11: comparing performance across Australia. Sydney: COAG Reform Council, 2012.

- 21. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Healthy for Life — Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services: report card. Canberra: AIHW, 2013. (AIHW Cat. No. IHW 97.)

- 22. Grant M, Wronski I, Murray RB, Couzos S. Aboriginal health and history. In: Couzos S, Murray R, editors. Aboriginal primary health care. An evidence based approach. 3rd ed. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2008: 1-28.

- 23. National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. National data protocols for the routine collection of standardised data on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Canberra: NACCHO, 1997. http://www.naccho.org.au/download/naccho-historical/NACCHO%20Protocols.pdf (accessed Sep 2014).

- 24. National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. Constitution for the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. Canberra: NACCHO, 2011. http://www.naccho.org.au/download/naccho-governance/NACCHO%20CONSTITUTION%20Ratified%20Ver%20151111%20for%20ASIC%20.pdf (accessed Sep 2014).

- 25. International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Defining the role of authors and contributors. http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html (accessed Mar 2014).

- 26. Kelly J, Saggers S, Taylor K, et al. “Makes you proud to be black eh?”: Reflections on meaningful Indigenous research participation. Int J Equity Health 2012; 11: 40.

- 27. Bailey S, Hunt J. Successful partnerships are the key to improving Aboriginal health. N S W Public Health Bull 2012; 23: 48-51.

- 28. Maar MA, Lightfoot NE, Sutherland ME, et al. Thinking outside the box: Aboriginal people's suggestions for conducting health studies with Aboriginal communities. Public Health 2011; 125: 747-753.

- 29. Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health 2006; 27: 1-28.

- 30. Tuhiwai Smith L. Articulating an indigenous research agenda. In: Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. 2nd ed. London: Zed Books, 2012: 127-142.

- 31. Wallerstein N. What is the evidence on effectiveness of empowerment to improve health? Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2006. (Health Evidence Network report.) http://www.euro.who.int/en/data-and-evidence/evidence-informed-policy-making/publications/pre2009/what-is-the-evidence-on-effectiveness-of-empowerment-to-improve-health (accessed Sep 2014).

- 32. Bonevski B, Randell M, Paul C, et al. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14: 42.

Abstract

Objective: To describe the Talking About The Smokes (TATS) project according to the World Health Organization guiding principles for conducting community-based participatory research (PR) involving indigenous peoples, to assist others planning large-scale PR projects.

Design, setting and participants: The TATS project was initiated in Australia in 2010 as part of the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project, and surveyed a representative sample of 2522 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults to assess the impact of tobacco control policies. The PR process of the TATS project, which aimed to build partnerships to create equitable conditions for knowledge production, was mapped and summarised onto a framework adapted from the WHO principles.

Main outcome measures: Processes describing consultation and approval, partnerships and research agreements, communication, funding, ethics and consent, data and benefits of the research.

Results: The TATS project involved baseline and follow-up surveys conducted in 34 Aboriginal community-controlled health services and one Torres Strait community. Consistent with the WHO PR principles, the TATS project built on community priorities and strengths through strategic partnerships from project inception, and demonstrated the value of research agreements and trusting relationships to foster shared decision making, capacity building and a commitment to Indigenous data ownership.

Conclusions: Community-based PR methodology, by definition, needs adaptation to local settings and priorities. The TATS project demonstrates that large-scale research can be participatory, with strong Indigenous community engagement and benefits.