Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people (referred to here as Indigenous Australians) have poorer rates of cancer survival than non-Indigenous people.1 Because ascertainment of Indigenous status in routinely collected data sources is incomplete, analysis of population-based cancer registry data has been largely restricted to registries known to have high-quality data ascertainment, such as those in Queensland, Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia.2 The limited data that are available show a consistent picture of similar overall cancer incidence, but lower incidences of some cancers that have a better prognosis (such as melanoma) and higher incidences of cancers with poorer prognoses.3

Recent studies have highlighted significantly lower survival among Indigenous patients with cancer compared with non-Indigenous patients.1,4-8 Although Indigenous people are more likely to be diagnosed at advanced stages with certain cancers, or to receive less treatment, this does not completely explain the survival disadvantage.5-7 A matched case–case study in Queensland found that Indigenous patients treated in the public health system were 30% more likely to die from their cancer than non-Indigenous patients after adjusting for stage, cancer treatment and comorbid conditions.8

A higher proportion of Indigenous Australians than non-Indigenous Australians live in remote areas.9 Many remote areas are also characterised by socioeconomic disadvantage, with both remoteness10,11 and area-socioeconomic disadvantage12 associated with lower cancer survival. Currently, however, there is limited information on how the Indigenous survival differential varies across categories of remoteness and area-socioeconomic disadvantage. In this population-based study, we sought to address this lack of knowledge, and thus inform further research, policy and clinical priorities aimed at redressing the survival inequalities currently experienced by Indigenous people with cancer.

Data were provided by the population-based Queensland Cancer Registry (QCR),13 under an agreement between Cancer Council Queensland and Queensland Health allowing access to non-identifiable data. For these analyses, all people of known Indigenous status aged 15 years and over who were diagnosed with a primary invasive cancer (International classification of diseases for oncology, 3rd edition [ICD-O-3] codes, C00–C80) during 1 January 1997 to 31 December 2006 were included. We excluded people whose age or residential location at diagnosis was unknown, or whose diagnosis was based on the death certificate or autopsy report only. Cases included in the study were followed to 31 December 2007, with matching to the National Death Index. Those still alive at 31 December 2007 were censored at that date, while those who died from a cause other than the diagnosed cancer were censored at their date of death.

Since the differential in the incidence of cancer between Indigenous and non-Indigenous depends on cancer type, with cancers common among Indigenous people more likely to be associated with low survival rates,14 we constructed a variable representing broad cancer groups based on 5-year cancer survival estimates for all of Queensland13 to include in the analysis. These estimates were: < 25% (eg, cancers of the oesophagus, liver, lung, pancreas and unknown site); 25%–49% (eg, stomach and ovarian cancers, myeloid leukaemia, myeloma); 50%–74% (eg, colorectal and kidney cancers, non-Hodgkin lymphoma) and 75%–100% (eg, breast, cervical and prostate cancers and melanoma).

Residential location at diagnosis was obtained from the QCR, according to Statistical Local Area (SLA). These SLAs were then grouped according to the level of geographic remoteness based on the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+). Area-level socioeconomic disadvantage was measured by quintiles of the Index of Relative Socioeconomic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD), because this index is determined without including Indigenous status.15

Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to quantify the survival differences with Efron’s approximation used to resolve tied data (ie, multiple deaths at the same number of days from diagnosis).16 Data were analysed with Stata, version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex, USA).

A systematic process was used to develop the final model, considering the proportional hazards assumption, overall model fit and the influence exerted by individual cases. Scaled Schoenfeld residuals, which test for non-zero slope over time, were used to check if the proportional hazards assumptions were satisfied. Model goodness of fit was assessed by Cox–Snell residuals. Deviance residuals were then used to examine model accuracy. We considered the influence of individual cases to determine their impact on each of the estimated individual coefficients (using the DFBETA statistic) as well as their effect on the combined set of coefficients (using the LMAX statistic).16,17

Conditional survival, which reflects the average probability of an individual surviving a certain number of years given they have already survived for x years,18 was calculated for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous cohorts.

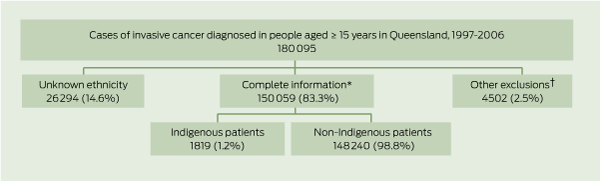

Of the original 180 095 people aged 15 years and over who were diagnosed with invasive cancer in Queensland between 1997 and 2006, 14.6% were of unknown ethnicity (Box 1). A further 2.5% were excluded because they were either diagnosed at death (total, 1.5%; Indigenous, 2.9%; non-Indigenous, 1.5%), did not have information on the SLA of residence (total, 0.8%; Indigenous, 0.7%; non-Indigenous, 0.8%) or the number of days between diagnosis and death (total, 0.2%; Indigenous, 0.3%; non-Indigenous, 0.2%), or did not have a SEIFA value assigned (total, 0; Indigenous, 0.4%; non-Indigenous, 0). The final cohort included 150 059 individuals of known ethnicity, of whom 1819 (1.2%) were Indigenous (Box 1). The most common cancers among Indigenous people were lung, breast, colorectal, prostate and cervical cancers. Among non-Indigenous people, the most common cancers were colorectal, breast, prostate and lung cancers and melanoma. A slight majority (55.5%) of people diagnosed with cancers were males.

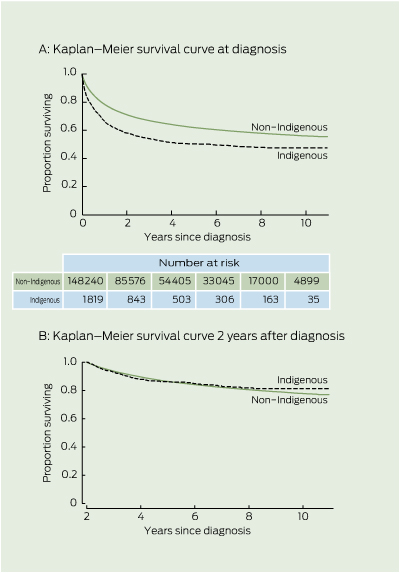

There was clear evidence of lower cancer survival for Indigenous compared with non-Indigenous people (Box 2 2A). The survival curves in Box 2 2A show the cumulative survival from diagnosis.

The plot of the hazard function by Indigenous status (not shown) revealed large initial differences in hazards, which decreased over time since diagnosis. After surviving 2 years, there was no difference in unadjusted cumulative survival by Indigenous status (Box 2 2B). Therefore, time-varying components (Indigenous status by follow-up years after diagnosis) were incorporated into the model. To prevent a few cases with longer follow-up exerting undue influence on survival estimates, time since diagnosis was categorised up to 5 + years of follow-up.

Survival estimates and results from the final Cox hazard model are shown in Box 3. Indigenous people experienced poorer survival during the first and second years after diagnosis after stratifying by age, sex and broad cancer site category, and adjusting for area-level disadvantage and remoteness. This disparity decreased with time since diagnosis, and after 2 years there was no survival disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous patients with cancer.

Conditional survival estimates (Box 4) reinforce the time-dependent nature of the differential in survival between Indigenous and non-Indigenous patients with cancer. Indigenous patients initially had poorer 5-year survival prognoses than non-Indigenous patients, but this disparity in survival expectations vanished once they had survived 2 or more years.

In this population-based study of cancer in Queensland, we found significant disparities between the survival outcomes for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people after their diagnosis. These differences remained after accounting for remoteness, area-socioeconomic disadvantage, age group, sex and mix of cancers. However, this survival disparity was modified by time since diagnosis, with the comparative risk of death decreasing as the time from diagnosis increased. This varying time effect has not been previously noted in studies examining cancer survival among Indigenous people in Australia,4,19 apart from a brief mention of time-varying comparative Indigenous and non-Indigenous survival in patients with colorectal cancer in the Northern Territory.20

However, this optimism must be constrained by a strong call to action to understand what is causing the very wide disparity in survival within the first 1 to 2 years after diagnosis. A recent Queensland study showed a survival differential for Indigenous patients with breast cancer that remained even after adjusting for spread of disease.21 This suggests that other factors, such as the impact of poorer general health and increased comorbid conditions among the Indigenous compared with the non-Indigenous population, also play an important role. There may be a healthy cohort effect, as Indigenous patients who survive beyond 2 years after diagnosis may have fewer comorbid conditions or better general health than those who died earlier. Alternatively, Indigenous patients with cancer in Queensland (all cancers) are less likely to undergo treatment for their cancer than other patients.8 Indigenous patients who use health services and receive adequate treatment may have better rates of survival.22 Until Australian cancer registries standardise the collection and recording of stage and treatment data, it will be impossible to explore these factors appropriately.

We found no evidence that the differential in Indigenous versus non-Indigenous survival varied according to geographical area of residence. As the use of any area-based measure of socioeconomic status is likely to over-estimate the affluence of Indigenous people,23 this reinforces the lack of evidence. This may indicate the Indigenous survival differential is not primarily related to access to treatment or socioeconomic barriers, but that other as yet unknown factors are more relevant, including those related to culture and general health, and that these other factors have similar impact across geographical locations. Clearly, having an almost 50% differential in cancer survival within the first 12 months of diagnosis is not acceptable, and our findings should increase the motivation for further efforts in this area. Greater emphasis and research focus should therefore be placed on identifying the factors responsible for the early disparity in survival.

Limitations of our study include the relatively small numbers of Indigenous cases, which gave us limited capacity to investigate differences for specific types of cancer. We were also unable to separate the effects of early diagnosis from other factors, including those of treatment differentials. As it is possible that not all cases of cancer in Indigenous people were identified, there is potential misclassification of true Indigenous status. However, this misclassification is thought to be small,8 and ascertainment is considered high.2

2 Comparison of survival between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people aged ≥ 15 years diagnosed with invasive cancers in Queensland, 1997–2006

3 Cause-specific survival estimates and Cox proportional hazard ratios for all people aged ≥ 15 years diagnosed with invasive cancers in Queensland, 1997–2006

Risk of death among Indigenous compared with non-Indigenous people§ |

|||||||||||||||

Received 15 September 2011, accepted 13 December 2011

- Susanna M Cramb1

- Gail Garvey2

- Patricia C Valery2

- John D Williamson3

- Peter D Baade1

- 1 Viertel Centre for Research in Cancer Control, Cancer Council Queensland, Brisbane, QLD.

- 2 Epidemiology and Health Services Division, Menzies School of Health Research, Brisbane, QLD.

- 3 Policy, Strategy and Resourcing Division, Queensland Health, Brisbane, QLD.

We thank John Condon, Menzies School of Health Research, Charles Darwin University, for his review of a previous draft of this manuscript. Peter Baade was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship (No. 1005334). Patricia Valery was supported by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (No. FT100100511).

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Chong A, Roder D. Exploring differences in survival from cancer among Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians: implications for health service delivery and research. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev 2010; 11: 953-961.

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Indigenous identification in hospital separations data: quality report. AIHW: Canberra, 2010. (AIHW Cat. no. HSE 85; Health Services Series No. 35.) http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442468330 (accessed Feb 2012).

- 3. Cunningham J, Rumbold AR, Zhang X, et al. Incidence, aetiology, and outcomes of cancer in Indigenous peoples in Australia. Lancet Oncol 2008; 9: 585-595.

- 4. Condon JR, Armstrong BK, Barnes T, et al. Cancer incidence and survival for indigenous Australians in the Northern Territory. Aust N Z J Public Health 2005; 29: 123-128.

- 5. Condon JR, Barnes T, Armstrong BK, et al. Stage at diagnosis and cancer survival for Indigenous Australians in the Northern Territory. Med J Aust 2005; 182: 277-280. <MJA full text>

- 6. Condon JR, Cunningham J, Barnes T, et al. Cancer diagnosis and treatment in the Northern Territory: assessing health service performance for indigenous Australians. Intern Med J 2006; 36: 498-505.

- 7. Hall SE, Bulsara CE, Bulsara MK, et al. Treatment patterns for cancer in Western Australia: does being Indigenous make a difference? Med J Aust 2004; 181: 191-194. <MJA full text>

- 8. Valery PC, Coory M, Stirling J, et al. Cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survival in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians: a matched cohort study. Lancet 2006; 367: 1842-1848.

- 9. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Canberra: ABS, 2008. (ABS Cat. No. 4704.0.) http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4704.02008?Open Document (accessed Feb 2012).

- 10. Cramb SM, Mengersen KL, Baade PD. Atlas of cancer in Queensland: geographical variation in incidence and survival, 1998–2007. Brisbane: Viertel Centre for Research in Cancer Control, Cancer Council Queensland, 2011. (accessed Feb 2012). <MJA full text>

- 11. Jong KE, Smith DP, Yu XQ, et al. Remoteness of residence and survival from cancer in New South Wales. Med J Aust 2004; 180: 618-622. <MJA full text>

- 12. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer survival and prevalence in Australia: cancers diagnosed from 1982 to 2004. Canberra: AIHW, 2008. (AIHW Cat. No. CAN 38; Cancer Series No. 42.) http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442468141 (accessed Feb 2012).

- 13. Queensland Cancer Registry. Cancer in Queensland 1982 to 2008. Incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence. Brisbane: Cancer Council Queensland, 2011. http://www.cancerqld.org.au/cancer-registry/CRQQ4072%20CRR_Content_FINAL_NEW%201.1.pdf (accessed Feb 2012).

- 14. Condon JR, Armstrong BK, Barnes A, et al. Cancer in Indigenous Australians: a review. Cancer Cause Control 2003; 14: 109-121.

- 15. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Information paper: an introduction to socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), 2006. Canberra: ABS, 2008. (ABS Cat. No. 2039.0.) http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/2039.0 (accessed Feb 2012).

- 16. Cleves M, Gutierrez RG, Gould W, et al. An introduction to survival analysis using Stata. 3rd ed. College Station: Stata Press, 2010.

- 17. Collett D. Modelling survival data in medical research. 2nd ed. London: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2003.

- 18. Baade PD, Youlden DR, Chambers SK. When do I know I am cured? Using conditional estimates to provide better information about cancer survival prospects. Med J Aust 2011; 194: 73-77. <MJA full text>

- 19. Roder D, Currow D. Cancer in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of Australia. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev 2009; 10: 729-733.

- 20. Condon JR, Barnes A, Armstrong BK, et al. Stage at diagnosis and cancer survival of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in the Northern Territory, 1991–2000. Melbourne: National Cancer Control Initiative, 2005.

- 21. Dasgupta P, Baade PD, Aitken JF, Turrell G. Multilevel determinants of breast cancer survival: association with geographic remoteness and area-level socioeconomic disadvantage. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011. 9 Dec [Epub ahead of print].

- 22. Coory MD, Green AC, Stirling J, Valery PC. Survival of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Queenslanders after a diagnosis of lung cancer: a matched cohort study. Med J Aust 2008; 188: 562-566. <MJA full text>

- 23. Kennedy B, Firman D. Indigenous SEIFA – revealing the ecological fallacy. Population and Society: Issues, Research, Policy. 12th Biennial Conference of the Australian Population Association; 2004 15-17 Sep; Canberra: APA, 2004. http://www.apa.org.au/upload/2004-4E_Kennedy.pdf (accessed Feb 2012).

Abstract

Objective: To examine the differential in cancer survival between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Queensland in relation to time after diagnosis, remoteness and area-socioeconomic disadvantage.

Design, setting and participants: Descriptive study of population-based data on all 150 059 Queensland residents of known Indigenous status aged 15 years and over who were diagnosed with a primary invasive cancer during 1997–2006.

Main outcome measures: Hazard ratios for the categories of area-socioeconomic disadvantage, remoteness and Indigenous status, as well as conditional 5-year survival estimates.

Results: Five-year survival was lower for Indigenous people diagnosed with cancer (50.3%; 95% CI, 47.8%–52.8%) compared with non-Indigenous people (61.9%; 95% CI, 61.7%–62.2%). There was no evidence that this differential varied by remoteness (P = 0.780) or area-socioeconomic disadvantage (P = 0.845). However, it did vary by time after diagnosis. In a time-varying survival model stratified by age, sex and cancer type, the 50% excess mortality in the first year (adjusted HR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.38–1.63) reduced to near unity at 2 years after diagnosis (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.78–1.35).

Conclusions: After a wide disparity in cancer survival in the first 2 years after diagnosis, Indigenous patients with cancer who survive these 2 years have a similar outlook to non-Indigenous patients. Access to services and socioeconomic factors are unlikely to be the main causes of the early lower Indigenous survival, as patterns were similar across remoteness and area-socioeconomic disadvantage. There is an urgent need to identify the factors leading to poor outcomes early after diagnosis among Indigenous people with cancer.