The number of Australians being diagnosed and living with cancer is rising sharply.1,2 Typically, patients with newly diagnosed cancers are informed of their prognosis according to published Australian estimates of observed or relative survival calculated from the date of diagnosis. As time passes, standard relative survival estimates are of limited relevance because they include survival information for people who have already died. However, these initial survival estimates continue to loom large in patients’ minds. A more relevant and useful question may be: “Now that I have survived for x number of years, what is the probability that I will survive another y years?”.

Conditional survival directly addresses this question, and has been shown to provide much more useful and clinically reliable estimates of survival probability for cancer survivors.3

While estimates for conditional survival have been reported in the international literature for a range of cancers,3-10 only estimates for breast cancer have been published based on Australian data.11,12 In this article, we present population-based conditional survival estimates for patients diagnosed with cancer in Queensland, Australia.

The data required for this study were non-identifiable, so ethics committee involvement was not necessary. The study received no external funding.

De-identified case records were obtained from the population-based Queensland Cancer Registry (QCR) with notification of invasive cancers required by law.13 We restricted our cohort to patients aged 15–89 years at the time they were diagnosed with cancer. Survival status is obtained through routine record linkage of the QCR data with the National Death Index which enables interstate deaths to be identified.

All patients with cancer diagnosed from 1982 through to 2007 were included in the cohort, with follow-up to 31 December 2007. We restricted cancer-specific analyses to the 13 most common types of invasive cancer (Box 1) defined using the International classification of diseases for oncology, third revision,13 and all invasive cancers combined (including cancers other than those 13).

Relative survival is used to approximate disease-specific survival, and is routinely reported by international cancer registries because it does not rely on accurate cause of death coding. We calculated relative survival estimates using actuarial methods and based on period analysis,14 with patients with cancer being considered at risk between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2007. Expected survival was based on the Ederer II method.15 The survival time of patients who were not known to have died before 31 December 2007 was censored as of that date.

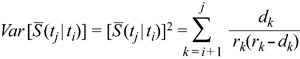

Conditional survival (CS) is the probability of surviving an additional y years given that the person has already survived x years. It is calculated by dividing the relative survival at (x + y) years after diagnosis by the relative survival at x years after diagnosis.16 Confidence intervals can be calculated with the following variance formula:16

Given m time intervals, dk is the number of deaths and rk is the number at risk during the kth interval. The probability of survival past time t is given by S (t), so S (tj | ti) is the probability of survival past time tj, given patients have already survived past time ti. The 95% CIs are then constructed assuming that the CS rates follow a normal distribution.

Box 1 shows the 5-year relative survival estimates at diagnosis for each of the 13 selected cancer types, along with 5-year CS estimates for patients who have survived 1, 3, 5, 7 and 10 years after diagnosis.

As an example, people diagnosed with stomach cancer have an initial 5-year relative survival estimate of 29%. However, if these patients survive for a year, their conditional 5-year relative survival percentage increases to 53%, and reaches 101% if they survive 10 years after diagnosis. In contrast, while 5-year relative survival is initially higher for patients with leukaemia at the time of diagnosis (58%), the 5-year CS estimate is lower for these patients than for patients with stomach cancer 10 years after diagnosis (82%).

Estimated relative survival at diagnosis and conditional relative survival curves calculated at 1, 3 and 5 years after diagnosis are shown in Box 2. For each type of cancer, the survival curves become progressively flatter and move closer to 100% survival the longer after diagnosis that the CS estimate begins. The differences in the survival curves are most pronounced when the initial survival prognosis is poorer, such as for cancers of the stomach, pancreas and lung. In contrast, the differences in survival curves are less substantial for cancers with a very good initial prognosis, such as melanoma and thyroid cancer.

Box 3 shows conditional 5-year relative survival for each additional year survived for selected cancers by age group. The improved survival prognosis at diagnosis for younger patients was generally maintained over time, but for most cancers the age-differential decreased.

Conditional survival estimates provide quantitative data for what is often observed anecdotally in clinical settings — that there is a subset of patients who survive beyond what would have been predicted at the time of their diagnosis, and that the long-term prognosis for these patients continues to improve. This is critical information for cancer survivors to receive and understand. One of the most common unmet psychological needs cancer survivors report is fear that their cancer will recur;17 and fear of cancer recurrence is related to lower quality of life.18 A clearer understanding that survival after cancer is a conditional event may help patients with cancer derive more hopeful appraisals about the future, and potentially decrease the anxiety that often accompanies post-treatment surveillance.

It has been suggested that when conditional 5-year relative survival exceeds 95% (ie, survival is almost identical to the general population with the same age structure) the excess mortality is negligible.8,9 In our study, this was found to occur within 10 years of diagnosis for all cancers combined, along with patients diagnosed with stomach cancer, colorectal cancer, melanoma, cervical cancer and thyroid cancer, similar to the results observed in international studies.8,9,19 Older patients and people diagnosed with other cancers continue to have poorer survival compared with the age-matched general population. Reasons for this continued excess mortality are varied, but would include late recurrences or adverse treatment effects, secondary tumours or increased comorbidities.8,9

The value of the additional information provided by CS estimates is greatest for people diagnosed with cancers associated with an initially poor prognosis. Unfortunately, the proportion of patients with these cancers who live to experience the improved survival outcomes is relatively low. However for patients who do survive 1, 3 and 5 years after diagnosis, access to updated information for each point of their cancer recovery is important, providing scope for evidence-based optimism as they progress on the survivor’s journey.

Cancer survivors are faced with increased uncertainty about their future at a time when they need to make important life decisions. Overall quality of life among cancer survivors has been shown to be influenced by the domains of control, uncertainty and the future.20 Levels of anxiety in each of these three domains may be alleviated, in part, by an understanding of the increased likelihood of continued survival over time.3 Thus, by acknowledging that risk profiles for cancer survivors change over time, CS estimates have the potential to be especially relevant for survivors and their families as part of any mid-term to longer-term follow up and support programs.

Current Australian guidelines for the psychosocial care of adults with cancer advise that, when discussing prognosis, clinicians should provide examples of extraordinary survivors to give hope.21 By contrast, we suggest that it would be better if patients understood that the further they progress from the time of diagnosis, the greater their chance of surviving longer will become. This knowledge may be more effective in building realistic hope and assisting people to manage uncertainty about the future.

A strength of our study was the use of statewide population-based data to calculate CS estimates, with information collected over 26 years. Applying a period analysis14 allowed us to calculate long-term CS based on the most recent outcomes available (ie, patients at risk between 1998 and 2007), in recognition of improvements in cancer survival during the past two to three decades.

Limitations of our study include the lack of stage or treatment data. Stage at diagnosis is known to be an important prognostic factor for survival outcomes.22 However, its impact reduces and can disappear for long-term CS.9 Like all Australian cancer registries, the QCR does not routinely collect information about clinical stage, although the New South Wales Central Cancer Registry does collect some information about the spread of disease. Cancer treatment can potentially have a dual effect on survival as it can bring about remission but may also have long-term adverse effects.23 As is recommended for international cancer registries,9 moves towards standardised collection and recording of stage and treatment data by population-based cancer registries in Australia should be a matter of priority.

Since CS estimates have the potential to provide important information for cancer clinicians, patients and their carers, we suggest that measures of CS be incorporated into routine statistical reporting in Australia.

1 Conditional 5-year relative survival estimates, by type of cancer and number of years after diagnosis, for patients aged 15–89 years at diagnosis, Queensland 1998–2007

2 Conditional relative survival curves at diagnosis, 1 year, 3 years and 5 years after diagnosis, Queensland, 1998–2007

Survival estimates were calculated by period analysis, including patients at risk from selected cancers between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2007 in Queensland. Survival curves represent the percentage of patients (y-axis) surviving the specified years after diagnosis (x-axis), given they have already survived a specified number of years. Vertical lines represent the 95% confidence intervals for the conditional survival estimates. Not all y-axes begin at the origin. |

3 Conditional 5-year relative survival for every additional year survived after initial diagnosis of cancer, according to age group and cancer type, Queensland, 1998–2007

Survival estimates were calculated by period analysis, including patients at risk from selected cancers between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2007 in Queensland. Survival curves represent the percentage of patients (y-axis) surviving the specified years after diagnosis (x-axis), given they have already survived a specified number of years. Vertical lines represent the 95% confidence intervals for the conditional survival estimates. Numbers of patients with some cancers (stomach, pancreatic, thyroid and cervical) were not sufficient to provide stable long-term age-specific conditional survival estimates. Not all y-axes begin at the origin. |

Received 12 May 2010, accepted 7 October 2010

- Peter D Baade1,2

- Danny R Youlden1

- Suzanne K Chambers1,3

- 1 Viertel Centre for Research in Cancer Control, Cancer Council Queensland, Brisbane, QLD.

- 2 School of Public Health, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD.

- 3 Griffith Health Institute, Griffith University, Gold Coast, QLD.

None identified.

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Cancer Incidence and Mortality (ACIM) Books [Internet]. Canberra: AIHW, 2010. http://www.aihw.gov.au/cancer/data/acim_books/index.cfm (accessed Nov 2010).

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Cancer Australia and Australasian Association of Cancer Registries. Cancer survival and prevalence in Australia: cancers diagnosed from 1982 to 2004. Cancer Series no. 42. Canberra: AIHW, 2008. (Cat. no. CAN 38.) http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/10484 (accessed Nov 2010).

- 3. Xing Y, Chang GJ, Hu CY, et al. Conditional survival estimates improve over time for patients with advanced melanoma: results from a population-based analysis. Cancer 2010; 116: 2234-2241.

- 4. Yang YH, Liu SH, Ho PS, et al. Conditional survival rates of buccal and tongue cancer patients: how far does the benefit go? Oral Oncol 2009; 45: 177-183.

- 5. Chang GJ, Hu CY, Eng C, et al. Practical application of a calculator for conditional survival in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 5938-5943.

- 6. Alanee S, Shukla A. Paediatric testicular cancer: an updated review of incidence and conditional survival from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. BJU Int 2009; 104: 1280-1283.

- 7. Choi M, Fuller CD, Thomas CR Jr, et al. Conditional survival in ovarian cancer: results from the SEER dataset 1988–2001. Gynecol Oncol 2008; 109: 203-209.

- 8. Janssen-Heijnen ML, Houterman S, Lemmens VE, et al. Prognosis for long-term survivors of cancer. Ann Oncol 2007; 18: 1408-1413.

- 9. Janssen-Heijnen ML, Gondos A, Bray F, et al. Clinical relevance of conditional survival of cancer patients in Europe: age-specific analyses of 13 cancers. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 2520-2528.

- 10. Bowles TL, Xing Y, Hu CY, et al. Conditional survival estimates improve over 5 years for melanoma survivors with node-positive disease. Ann Surg Oncol 2010; 17: 2015-2023.

- 11. Hahnel R, Spilsbury K. Oestrogen receptors revisited: long-term follow up of over five thousand breast cancer patients. ANZ J Surg 2004; 74: 957-960.

- 12. Woods LM, Rachet B, O’Connell D, et al. Large differences in patterns of breast cancer survival between Australia and England: a comparative study using cancer registry data. Int J Cancer 2009; 124: 2391-2399.

- 13. Queensland Cancer Registry, Cancer Council Queensland and Queensland Health. Cancer in Queensland: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence, 1982 to 2007. Brisbane: Cancer Council Queensland, 2010.

- 14. Brenner H, Gefeller O, Hakulinen T. Period analysis for “up-to-date” cancer survival data: theory, empirical evaluation, computational realisation and applications. Eur J Cancer 2004; 40: 326-335.

- 15. Ederer F, Heise H. Instructions to IBM 650 programmers in processing survival computations. Methodological Note No. 10. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 1959.

- 16. Skuladottir H, Olsen JH. Conditional survival of patients with the four major histologic subgroups of lung cancer in Denmark. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 3035-3040.

- 17. McDowell ME, Occhipinti S, Ferguson M, et al. Predictors of change in unmet supportive care needs in cancer. Psychooncology 2010; 19: 508-516.

- 18. Hart SL, Latini DM, Cowan JE, et al. Fear of recurrence, treatment satisfaction, and quality of life after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer 2008; 16: 161-169.

- 19. Merrill RM, Henson DE, Ries LA. Conditional survival estimates in 34 963 patients with invasive carcinoma of the colon. Dis Colon Rectum 1998; 41: 1097-1106.

- 20. Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M. Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res 1995; 4: 523-531.

- 21. National Breast Cancer Centre and National Cancer Control Initiative. Clinical practice guidelines for the psychosocial care of adults with cancer. Sydney: NBBC, 2003. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/publications/synopses/cp90.pdf (accessed Nov 2010).

- 22. Greene FL, Sobin LH. The staging of cancer: a retrospective and prospective appraisal. CA Cancer J Clin 2008; 58: 180-190.

- 23. Mller KD, Triano LR. Medical issues in cancer survivors — a review. Cancer J 2008; 14: 375-387.

Abstract

Objective: To report the latest conditional survival estimates for patients with cancer in Queensland, Australia.

Design, setting and participants: Descriptive study of state-wide population-based data from the Queensland Cancer Registry on patients aged 15–89 years who were diagnosed with invasive cancer between 1982 and 2007.

Main outcome measure: Conditional 5-year relative survival for the 13 most common types of invasive cancer, and all cancers combined.

Results: The prognosis for patients with cancer generally improves with each additional year that they survive. A significant excess in mortality compared with the general population ceases to occur within 10 years after diagnosis for survivors of stomach, colorectal, cervical and thyroid cancer and melanoma, with these groups having a conditional 5-year relative survival of at least 95% after 10 years. For the remaining cancers we studied (pancreatic, lung, breast, prostate, kidney, and bladder cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and leukaemia), conditional 5-year relative survival estimates (at 10 years after diagnosis) ranged from 82% to 94%, suggesting that patients in these cohorts continue to have poorer survival compared with the age-matched general population.

Conclusions: Estimates of conditional survival have the potential to provide useful information for cancer clinicians, patients and their carers as they are confronted by personal and surveillance-related decisions. This knowledge may be effective in building realistic hope and helping people manage uncertainty about the future. We suggest that measures of conditional survival be incorporated into routine statistical reporting in Australia.