We describe a case of acute liver failure and death associated with the use of a preparation containing the "natural" anxiolytic kava (Piper methysticum) and passionflower (Passiflora incarnata). The patient died after a report by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) warning of the potential for hepatotoxicity associated with the use of kava-containing products. The general public and alternative medicine practitioners need to be aware of the potential for non-prescription drugs to cause serious hepatic reactions.

In July 2002, a 56-year-old woman was referred to the Austin and Repatriation Medical Centre, Melbourne, for investigation of jaundice. She had been previously well apart from a history of benign monoclonal gammopathy (IgG, 24 g/L; normal, 6.9–15.4 g/L), which had been diagnosed 12 months previously.

The patient had presented to her local doctor with a two-week history of fatigue, nausea and increasing jaundice. She had no risk factors for viral hepatitis, no history of liver disease and drank minimal amounts of alcohol. Over the preceding three months she had been taking a herbal supplement for anxiety, prescribed and provided by a naturopath (Kava 1800 Plus, Eagle Pharmaceuticals, Castle Hill, NSW; one tablet thrice daily, labelled as containing kavalactones 60 mg, Passiflora incarnata 50 mg and Scutellaria laterifloria 100 mg). She had also been taking some vitamin and mineral supplements but no other medications.

Examination on presentation to hospital revealed the patient to be deeply jaundiced without stigmata of chronic liver disease. Relevant abnormal pathology test results are presented in Box 1. Extensive investigations to screen for recognised causes of acute liver failure failed to reveal any cause. Assays for acute hepatitis A, B, and C viruses, Epstein–Barr virus and cytomegalovirus were all negative. Serum copper and ceruloplasmin levels were normal and Kayser–Fleischer rings were not present. Antinuclear antibodies were detected at a titre of 1:160, but anti-smooth-muscle antibodies were not detected. No paracetamol was detected in the blood. An abdominal doppler ultrasound revealed a small liver with normal flow in the hepatic arteries, hepatic veins and portal veins. The paraprotein level had remained stable over the previous 12 months. A repeat bone marrow biopsy did not suggest the presence of multiple myeloma.

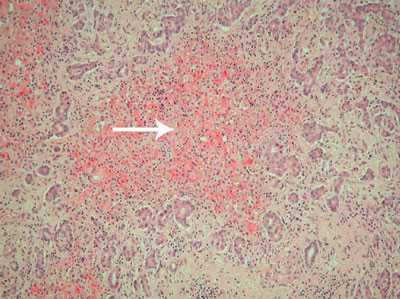

A trans-jugular liver biopsy performed on the fifth day of admission showed non-specific severe acute hepatitis with pan-acinar necrosis and collapse of hepatic lobules.

Over the subsequent week, the patient's condition deteriorated and she was urgently listed for transplantation.

On Day 17 of admission the patient underwent liver transplantation. Unfortunately, the procedure was complicated by massive bleeding that did not correct following implantation of the donor liver, and the patient died of progressive blood loss, hypotension and circulatory failure. Histological examination of the explanted liver confirmed the presence of massive hepatic necrosis (Box 2).

Subsequent analysis of the supplement she had taken revealed it contained kava and Passiflora incarnata as labelled, and a third, as yet unidentified, compound. Although the label listed Scutellaria laterifloria as an ingredient, none was identified in the compound.

This case report describes the first case of fulminant hepatic failure in Australia in a patient after taking a product containing kava and Passiflora incarnata. We used the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale1 and found it was "probable" that the kava-containing preparation caused this patient's illness. Worldwide, at least 68 cases of suspected hepatotoxicity associated with the use of kava-containing products have been reported, including six resulting in liver transplantation and three deaths. Passiflora incarnata has also been described in association with the development of hepatotoxicity, but in only one case report, involving a patient who took several herbal medicines, including Passiflora incarnata.2 In February 2002 (despite the absence of any Australian reports of kava-associated hepatotoxicity), the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) issued an alert regarding the potential hepatotoxicity of kava-containing products.3 This alert was widely distributed to doctors, pharmacists and alternative medicine practitioners. The patient we described began taking a kava-containing preparation after the TGA alert was issued, and apparently was unaware of the alert.

Medication reactions resulting in abnormalities of liver function tests are relatively common, yet rarely result in severe liver injury. It is important to take a careful history of any drug or herbal remedy use in all patients with unexplained hepatitis, as the continuation of the agent after the onset of injury may have catastrophic consequences. Spontaneous recovery is unlikely in patients who develop encephalopathy or severe coagulopathy, and in such cases liver transplantation may offer the only realistic chance of survival.4

This report emphasises the need for the general public and alternative medicine practitioners to be aware of the potential for non-prescription drugs to cause serious hepatic reactions. The lack of regulation within the alternative medicine community and general availability of non-prescribed medications may have contributed to the death of this woman. A statutory obligation for dispensers of non-prescribed medications to provide information to the consumer at the point of sale regarding any future drug alerts may help to limit further morbidity and mortality.

1: Patient laboratory data on presentation to hospital and 17 days later (day of transplantation)

|

Serum albumin (g/L) (normal, 35–50 g/L) |

Serum bilirubin (μmol/L) (normal, < 18 μmol/L) |

Serum alkaline phosphatase (U/L) (normal, 40–129 U/L) |

Serum alanine aminotransferase (U/L) (normal, < 55 U/L) |

International normalised ratio (normal, 1–1.2) |

||||||

Presentation |

34 |

209 |

190 |

4539 |

2.3 |

||||||

Day 17 |

23 |

607 |

357 |

438 |

6.6 |

||||||

2: Histological section of the explanted liver

The image shows an "empty" necrotic lobule which is devoid of hepatocytes (arrow). This is surrounded by proliferating bile ductules derived from portal tracts. Much of the liver had this appearance. (Haematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification × 100. Image prepared by Mr Simon Rosalie.)

- 1. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981; 30: 239-245.

- 2. Whiting PW, Clouston A, Kerlin P. Black cohosh and other herbal remedies associated with acute hepatitis. Med J Aust 2002; 177: 440-443. <MJA full text>

- 3. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Kava practitioner alert. Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/tga/docs/html/kavapa.htm (accessed Dec 2002).

- 4. O'Grady JG, Alexander GJ, Hayllar KM, Williams R. Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure. Gastroenterology 1989; 97: 439-445.

None identified.