Let's not wait another 10 years

The forgotten children, the Australian Human Rights Commission's 2014 national inquiry into children in immigration detention, has come and gone. Its findings are clear and damning and should be a surprise to no one.1

A decade earlier, the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission released its national inquiry, A last resort?.2 It is unacceptable that we might wait another 10 years before such gross abuses cease and people are restored to both health and justice.

Further, the United Nations has named Australia for its breach of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.3 The medical community has been made aware of our ongoing human rights violations over the past decade.1,4-7 Ignorance is not an excuse that we can cling to for being part of this national embarrassment.

What more could be done to make us pay attention to the need to move beyond the multiple peak body position statements? They are only useful in as much as they highlight the chasm between acceptable standards of medical care and what we know is being practised in immigration detention.1,4-7

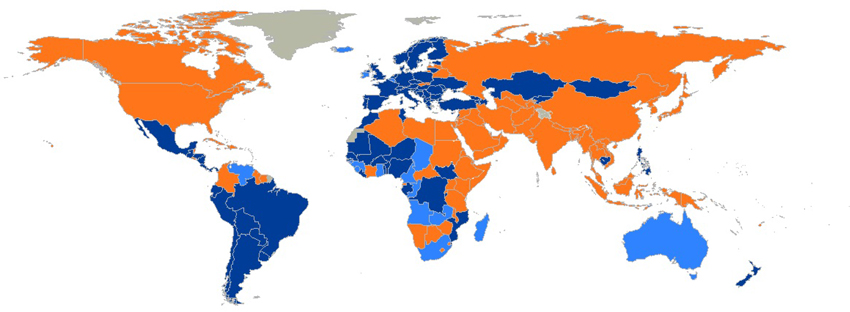

One option to increase genuine accountability would be to ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT). The OPCAT is a bipartisan-supported UN protocol signed by Australia in 2009. It is as yet unratified.6,8-10 At the time of publication, the OPCAT has been ratified by 78 countries (Box). It was established recognising the need to take measures beyond the simple agreement not to engage in the inhumane treatment of people in detention.8

Ratifying the OPCAT would ensure adequate oversight of the conditions of detention within Australia through the establishment of a national preventive mechanism (NPM) and through international scrutiny.8-10

Such a need for monitoring and independent oversight in immigration detention was not addressed through the establishment of the Detention Health Advisory Group in 2006, later remodelled as the Immigration Health Advisory Group, which was abandoned in 2013.11

An NPM would include a system of regular visits and reporting undertaken by independent national and international bodies. NPM assessments should inform legislation and intervention, as well as act as deterrents in their own right.8-10

An NPM would extend protections well beyond immigration detention centres. Monitoring would apply to people in all forms of detention where the protection of human rights is more challenging. This includes involuntary psychiatric admissions, aged care placements such as secure dementia wards, mental health facilities, forensic disability units, police lockups, juvenile detention centres and correctional environments.8-10

There is already considerable support for Australia's ratification of the OPCAT. This was demonstrated in September 2014 when 64 organisations wrote to the Attorney-General calling for its endorsement.6,12 Significant work has been completed on the requirements for implementation.9 Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory have released draft bills.6

We have the benefit of seeing different ways the OPCAT has been implemented and ratified internationally in comparable countries such as New Zealand and the United Kingdom (Box),9,10,12,13 where this process has led to strong review mechanisms with legal force that regulate places of detention of all kinds. These mechanisms also find expression in legislative changes to procedures in situations where human rights might otherwise be threatened.9,10,13

Such a mechanism would also assist in alleviating dual loyalty conflict experienced by the health workforce, whereby a lack of appropriate transparency and accountability leads to conflict between fulfilling duties to patients and the demands of employers. Many doctors and other health care providers have stated that such conflicts are commonplace in the detention of asylum seekers, as is a lack of ethical guidance when faced with decision making in the absence of a system grounded in human rights.4,5,14

For doctors, preserving and protecting the right to health falls squarely within our duty of care. As the World Medical Association makes clear:

As health professionals, physicians have a key role to play in providing high quality care to all patients without discrimination and preventing and reporting acts of torture and ill treatment that constitute gross human rights violations.15

Further, as all human rights are intimately connected, the preservation of the right to health serves to protect justice and dignity for asylum seekers. It is our obligation to ensure appropriate safeguards are put in place to regulate a clear separation between the management of health care and immigration policy. This is imperative when, despite the best intentions of the health care workforce and the bodies that represent them, we have thus far failed so badly.

1 Ratification of the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment*

Country status: dark blue = state party (78 countries); light blue = signatory (18 countries); orange = no action (101 countries). * Reproduced with permission from United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/OPCAT/Pages/OPCATIndex.aspx (accessed May 2015).

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Australian Human Rights Commission. The forgotten children: national inquiry into children in immigration detention 2014. Sydney: AHRC, 2014. https: //www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/forgotten_children_2014.pdf (accessed Apr 2015).

- 2. Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. A last resort? National inquiry into children in immigration detention. Sydney: HREOC, 2004. https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/human_rights/children_detention_report/report/PDF/alr_complete.pdf (accessed May 2015).

- 3. Méndez JE. Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Addendum: observations on communications transmitted to governments and replies received. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session28/Documents/A_HRC_28_68_Add.1_AV.doc (accessed Apr 2015).

- 4. Sanggaran J-P, Ferguson GM, Haire BG. Ethical challenges for doctors working in immigration detention. Med J Aust 2014; 201: 377-378. <MJA full text>

- 5. de Costa CM. Antenatal care for asylum seeker women: is “good enough” good enough? Med J Aust 2014; 201: 299-300. <MJA full text>

- 6. Australian Lawyers for Human Rights. Submission on Australia. 17 Oct 2014. United Nations Committee against Torture. 53rd session (3-28 Nov 2014). http://alhr.org.au/wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/ALHR-Submission-to-Committee-Against-Torture-17.10.14.pdf (accessed Apr 2015).

- 7. #HealthOrgsUnite. Australia's peak health groups call for all children to be released from immigration detention. 17 Mar 2015. https://twitter.com/hashtag/HealthOrgsUnite?src=hash (accessed Apr 2015).

- 8. UN General Assembly. Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment. 9 January 2003. A/RES/57/199. http://www.refworld.org/docid/3de6490b9.html (accessed May 2015).

- 9. Harding R, Morgan N. Implementing the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture: options for Australia. Australian Human Rights Commission, 2008. https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/rights-and-freedoms/publications/implementing-optional-protocol-convention-against-torture (accessed Apr 2015).

- 10. Australian Human Rights Commission. Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture (OPCAT). 1 Jan 2007. https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/asylum-seekers-and-refugees/projects/optional-protocol-convention-against-torture-opcat (accessed Apr 2015).

- 11. Australian Medical Association. AMA shocked by disbanding of Immigration Health Advisory Group (IHAG). 16 Dec 2013. https: //ama.com.au/media/ama-shocked-disbanding-immigration-health-advisory-group-ihag (accessed Apr 2015).

- 12. Human Rights Watch. Australia: joint letter to the Australian Government to ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture. 15 Sep 2014. http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/09/15/australia-joint-letter-australian-government-ratify-optional-protocol-convention-aga (accessed Apr 2015).

- 13. Association for the Prevention of Torture. United Kingdom – OPCAT ratification. http://www.apt.ch/en/opcat_pages/opcat-ratification-70 (accessed May 2015).

- 14. Briskman L, Zion D, Loff B. Challenge and collusion: health professionals and immigration detention in Australia. Int J Human Rights 2010; 14: 1092-1106.

- 15. World Medical Association. Health and human rights. http://www.wma.net/en/20activities/20humanrights (accessed May 2015).

We thank Corrine Dobson for her contribution to the preparation of this article.

No relevant disclosures.