Benzathine benzylpenicillin, also known as benzathine penicillin G (BPG), is a long‐acting penicillin. It is given by intramuscular injection, and used for the treatment of syphilis and for the prevention of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and progression to rheumatic heart disease (RHD).1 Globally, BPG comes in two preparations: a lyophilised powder which is suspended in diluent before administration, and a viscous aqueous suspension in pre‐filled syringes.1 In Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand and other high‐income countries, a pre‐filled formulation of Bicillin L‐A (Pfizer Australia) is used.

Bicillin L‐A is particularly important for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia, and Māori and Pacific peoples in Aotearoa New Zealand, as they account for 91% and 97% of ARF diagnoses, respectively.2,3 Similarly, syphilis notifications are inequitably represented in these First Nations populations.4,5

This disproportionate burden reflects the profound effects of colonisation. Political and social disempowerment, and separation from land, family, language, community and culture, are intrinsically harmful.6 These determinants also contribute to residential overcrowding (increasing the risk of Group A Streptococcus transmission) and health care that is not culturally safe (reducing the opportunity for disease‐altering treatment).7 A recent coronial inquest into the deaths of three young women from RHD highlighted that deficiencies in culturally safe care led to preventable tragedy.8

There is an established body of literature about barriers and enablers to BPG delivery.9,10,11,12 For ARF prevention, injection pain is a primary barrier to sustained successful delivery.13,14 Numerous “experiential considerations” are enablers of acceptability, including positive ongoing relationships with health providers, health literacy, ease of use, agency for decision making, impact on daily activities, and convenience.9,14 However, acceptability of Bicillin L‐A has not been considered through a cultural safety lens. Therefore, we completed a scoping review to identify clinical guidelines regarding administration of Bicillin L‐A.

Understanding existing guidance for administration of Bicillin L‐A in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand has practical implications. Recurrent Bicillin L‐A shortages in 2023 and 202415 prompted Australian agencies to arrange an alternative supply of a powered product through a Section 19A exemption,16 necessitating new administration advice. In addition, emerging research suggests that subcutaneous administration of high dose Bicillin L‐A is less painful and longer lasting than intramuscular delivery.17,18 Understanding existing administration guidelines is important to support stockout responses and facilitate new administration practices.19

Cultural safety considerations also warrant examination. Receiving a Bicillin L‐A injection is an intimate medical encounter that requires exposure of the buttocks, physical contact and pain. These features can engender feelings of vulnerability, further amplified in the context of colonisation. In Australia, people receiving secondary prophylaxis for RHD are predominantly Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, while their health care providers and those developing clinical guidelines are predominantly not.20 Clinical guidelines do not exist in a vacuum and are imbued with the priorities and approaches of the authors.21 The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (Ahpra) defines culturally safe practice as “the ongoing critical reflection of health practitioner knowledge, skills, attitudes, practising behaviours and power differentials in delivering safe, accessible and responsive healthcare free of racism”.22 Review of Bicillin L‐A administration guidelines provides an opportunity to explore this space in the context of a tangible and common clinical procedure.

Methods

This scoping review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR). A full statement of PRISMA‐ScR elements is presented in the Supporting Information (section 1).23

Search strategy

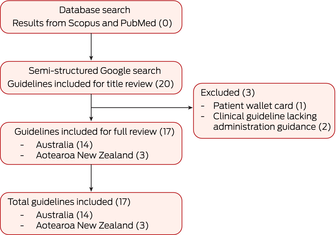

A systematic search was performed using two databases — Scopus and PubMed. The full electronic search strategy for these databases is presented in the Supporting Information (section 2). This yielded no significant results, and we proceeded to a semi‐structured Google search to identify publicly available clinical resources. The key search terms used were: “administration”, “injection”, “Bicillin L‐A”, “BPG”, “benzathine penicillin G”, “penicillin”, “New Zealand”, “Aotearoa” and “Australia”. The search was conducted by two authors (SV and RW) from 3 October to 18 December 2023.

Guideline appraisal

The AGREE II‐Global Rating Scale (AGREE II‐GRS) Instrument was used to assess completeness of guideline reporting within time, resource and relevance constraints.24 The primary investigator (SV) used the instrument’s 7‐point scale to preliminarily score all guidelines. These scores were blinded to the second reviewer (SJK), who independently scored all guidelines. Where there was more than a 2‐point discrepancy, consensus was obtained by additional reviewers (RW and LM). We were unable to identify any cultural safety audit tools adapted to analysis of written clinical guidelines and approached these considerations inductively.25

English language sources detailing administration guidance on Bicillin L‐A that were first released between 2013 and 2023 were included. Guidance in all formats was considered eligible, including written material and audiovisual training resources. Clinical guidelines solely focusing on Bicillin L‐A dosage without guidance on how to administer the product were excluded.

A standardised data extraction template was developed to identify key clinical variation between sources. The data extraction template was developed with input from all authors, and tabulated.

Thematic analysis

Preliminary inductive thematic analysis was iteratively developed during repeated review and rereading of guidelines by two authors (SV and RW). Emerging themes were reviewed for cultural relevance with LJW. Given the alignment of the themes with components of the Ahpra cultural safety definition, we shifted to a more deductive analytic model and formally adopted the components of the Ahpra definition as thematic categories. These evolved themes were recirculated and rediscussed by all authors.

Given the burden of RHD and the use of Bicillin L‐A in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, we applied the CONSIDER (Consolidated Criteria for Strengthening Reporting of Health Research Involving Indigenous Peoples) Statement.26 Detailed reporting is presented in the Supporting Information (section 3), grounded in the prioritisation of addressing Bicillin L‐A injection experience by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, Māori and Pacific Islander research participants.27

The authorship team includes people with cultural (LJW), clinical (LM, RW, SV) and product‐specific expertise (LM, RW). LJW (Wagadagam, Gumulgal, Zenadh Kes) has national expertise in cultural safety in clinical settings. LM (who is hospital based) and RW (who is community based) have completed clinical training and practice in Aotearoa New Zealand and in Australia. LM, RW and LJW all have experience in the development and use of clinical guidelines.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number H/2023/1112).

Results

Our search strategy yielded 14 Bicillin L‐A administration guidelines from Australia and three from Aotearoa New Zealand (Box 1). Using the data extraction template, we reviewed biomedical, pain reduction and experiential considerations for each guideline and conducted thematic analysis of findings. Full data extraction details are presented in the Supporting Information (section 4) and a summary of the comparison of the guidelines is provided in Box 2. Here, we report findings from our appraisal of the guidelines using AGREE II‐GRS, an overview of clinical variation between guidelines, and the results of our thematic analysis.

Appraisal of clinical guidelines

The AGREE II‐GRS appraisal of the clinical guidelines was of moderate–high guideline quality overall. On average, under domain one, seven guidelines scored 6 or above and ten guidelines scored 5.5 or below. Under domain two, seven guidelines scored 6 or above and ten guidelines scored 5.5 or below. Under domain three, seven guidelines scored 6 or above and ten guidelines scored 5.5 or below. Under domain four, three guidelines scored 6 or above and fourteen guidelines scored 5.5 or below (Supporting Information, section 5). The AGREE II‐GRS appraisal tool does not include cultural considerations.

Overview of clinical variation

Variation across guidelines was reviewed in four key areas — safe and effective delivery, pain reduction, experiential considerations, and post‐injection advice — plus other recommendations.

Safe and effective delivery

Safe and effective delivery of Bicillin L‐A includes technical considerations of needle gauge, injection site, and rate of injection delivery. Seven guidelines specified needle gauge, of which six recommended 21 gauge and one recommended 23 gauge. Most guidelines specified ventrogluteal, dorsogluteal or vastus lateralis to be acceptable sites of administration; only one did not state a recommended site for intramuscular injection. Eleven guidelines provided guidance on speed of administration: eight guidelines recommended the injection be delivered over 2–3 minutes, one specified over 1–2 minutes, and two simply stated “slowly”. Only two guidelines specified following the patient’s guidance or preference, alongside recommending that the injection be delivered over 2–3 minutes.

Pain reduction

Three main biomedical strategies were described to reduce pain on injection delivery: Bicillin L‐A temperature at administration, inclusion of local anaesthetic, and other administration adjuncts (ice packs and devices). Of the 17 guidelines, eight recommended the injection be delivered at “room temperature” and one recommended warming it to “body temperature”. Guidance included removing from fridge ahead of delivery and warming to body temperature by holding or rolling between hands. Twelve guidelines specified inclusion of local anaesthetic (lidocaine or lignocaine) to be co‐administered with the injection. The level of detail on use of local anaesthetic outlined across guidelines varied, as three guidelines simply stated its inclusion, while nine guidelines provided detailed information about the concentration and volume to be mixed into Bicillin L‐A syringes. Eleven guidelines recommended use of an ice pack. Timing of ice pack use was specified in ten, with eight specifying before injection and two specifying after injection. Nine guidelines specified use of oral and/or inhaled analgesia; all nine recommended oral pain relief, and paracetamol was specified in six guidelines. Alongside oral pain relief, three guidelines recommended inhaled analgesia (nitrous oxide [Entonox, BOC Gases Australia]). Several proprietary products for pain reduction were recommended: Buzzy4Shots (four guidelines), Bionix ShotBlocker (five guidelines) and Coolsense (one guideline). Additional pain reduction techniques included pressure applied to the site (before or after the injection) and injection site rotation between scheduled injections.

Non‐biomedical pain reduction recommendations were more varied. Nine of the 17 guidelines specified firm pressure to the injection site before delivery. Nine also recommended “distractors” including electronic games, talking, and other age‐appropriate methods. One guideline recommended patient encouragement and reassurance during injection delivery, talking about the importance of the injection, and encouragement and praise after the injection.

Experiential considerations

Three main strategies were described to improve the experience of receiving Bicillin L‐A. Four guidelines recommended minimising waiting time for people to receive their injection, three recommended rotation of injection site between scheduled injections, and six recommended considering patient preferences to inform site selection. Only Australian guidelines considered these experiential recommendations.

Post‐injection advice

Post‐injection advice was provided by eight guidelines. All of these recommended use of paracetamol as required for pain relief following injection, and a smaller number suggested movement of the affected limb following injection or application of warm or cool packs.

Other recommendations — patient interactions

One guideline (SA Health’s standing order) noted the importance of relationship strengthening activities for the patient, such as the use of incentives and rewards, and a patient‐focused, culturally safe environment.32 This guideline also specified involvement of family or a support person during injection procedures to improve the injection experience. One guideline from Aotearoa New Zealand (a Heart Foundation of New Zealand guideline) identified the importance of good rapport with the patient to support adherence, comprehension, and comfort, such as through having a designated nurse for each patient.28

Thematic analysis

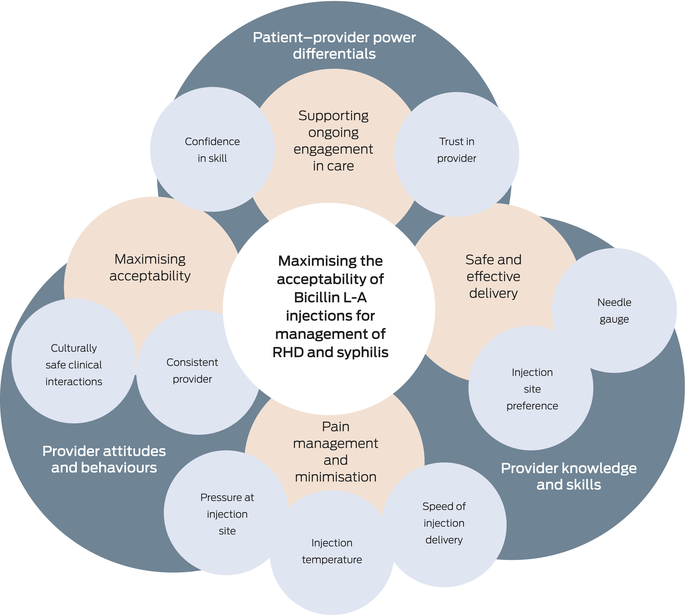

We considered components of Ahpra’s cultural safety definition (knowledge and skills, attitudes and practising behaviours, and power differentials) to explore whether individual components of Bicillin L‐A guidelines were enablers of culturally safe care, as shown in Box 3. Two guidelines are situated within larger documents which have a dedicated chapter or section focused on cultural considerations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Knowledge and skills

The knowledge and skills domain overlaps with the aforementioned details on safe and effective delivery, including needle gauge and injection site. There was little variation in the kind of clinical knowledge, and there was reasonable alignment with the Bicillin L‐A product information.45

Attitudes and practising behaviours

The attitudes and practising behaviours domain was largely related to pain reduction. Pain is commonly reported when people receive Bicillin L‐A injections, although the extent and experience of this pain varies between individuals and populations.20 One study of Aboriginal children receiving Bicillin L‐A for skin sore treatment found that 30% reported ongoing pain at the injection site 48 hours after delivery.46 Assessment and management of pain also occurs within a cultural context, particularly where demonstrations of pain may be suppressed to show bravery and stoicism or to minimise indignity.47,48

A growing evidence base of biomedical pain reduction strategies has developed over the past decade and some of these findings have been integrated into clinical guidelines. This is particularly the case for the addition of local anaesthetic to Bicillin L‐A injections, which has been studied in some detail and is now an accepted standard of care.49,50 Uptake of other pain reduction recommendations is more variable, spanning use of a Buzzy Bee vibration device, Buzzy4Shots vibrating ice pack, Bionix ShotBlocker and Coolsense numbing device. Use of proprietary products for pain relief raises equity issues, particularly for services providing a small number of Bicillin L‐A injections where it may not be viable to purchase pain‐reducing adjunct technology.

Power differentials

The autonomy and authority people feel in negotiating circumstances of injection delivery with their health care provider is key to the injection experience.9 The opportunity to negotiate circumstances is closely linked to the patient–provider relationship, and the trust and comfort the patient feels with their respective provider.20 As per the Ahpra framework, this ensures that the health care environment remains accessible and responsive for the patient and their needs. Furthermore, having a longstanding, positive relationship with the health care provider facilitates a patient’s ability to negotiate pain management strategies.20 Without opportunities to discuss pain mitigation strategies, patients may use the only power they have, which is to refuse and avoid the injections altogether.20

Facilitating agency may include offering a choice of injection administrator, particularly the option to have a same‐gendered administrator.51 Rapport with the clinical provider is a key determinant of patient engagement. Patients’ perceptions of pain are directly related to the health care worker administering the injection, the trust patients have in their ability, and the comfort provided during the injection procedure.52 When patients trusted and had a positive rapport with the nurse administering the injection, and trusted their ability to administer the injection, the perceived intensity of pain during the injection experience and duration of pain after the injection were reduced.14 Contrastingly, a negative perception towards the provider increased the patient’s duration of post‐injection pain and was a direct barrier to adherence.14 In addition, creating rapport with patients, particularly young children, is conducive to timely uptake of secondary prophylaxis.53 Having the close attention and interest of the same staff member who used appropriate language to communicate with the patient, and reassured patients of confidentiality, enhanced injection delivery.52

Only two of the 17 guidelines referred to a support person for the patient during injection delivery. This highlights a fundamental gap in clinical guidelines, as support from family and friends is a strong enabler for scheduled delivery of injections.14 Furthermore, family support directly correlates to patient education, as parents have reported increased understanding of the disease process and need for secondary prophylaxis.14

Discussion

This work demonstrates that there are multiple sources of guidance about how Bicillin L‐A is administered. Overall, these sources displayed little variation in technical details, some variation in pain reduction strategies and considerable variation in experiential considerations. The most striking finding was limited guidance on cultural safety considerations when delivering Bicillin L‐A injections.

Clinical guidelines cannot be agnostic to context or isolated from the populations they apply to. Rather, guidelines should consider health care delivery within the sociocultural context of colonisation and the dynamics of clinical encounters.6 This reflects the reality that culturally safe care is good clinical care, and normalises cultural considerations alongside biomedical ones. Although this scaffolding may not always be needed — such as when care is delivered by Indigenous people or organisations within an existing clinical relationship — it provides an important prompt for non‐Indigenous providers in other settings. This holistic approach may also contribute to addressing distress for providers administering Bicillin L‐A injections, associated with the pain caused and time taken to give these injections.20 Guidelines which address pain management and relational components of this procedure may support clinicians to record these details in their documentation of clinical notes. The process of recording and considering these issues may support reflective practice, which underpins culturally safe care.

The findings of this work have three overarching implications for future guideline development. First, clinical guidelines should prospectively consider cultural safety during development to enable safe clinical interactions that support the obligation of registered health professionals to provide cultural safe care. Second, leadership of Indigenous people and health service users would support this process and should be routinely reported. Third, the AGREE II‐GRS guidelines do not reflect cultural considerations and a specific cultural safety audit tool for clinical guidelines should be developed.

Limitations

Despite an iterative search strategy triangulated with clinical expertise, it is possible that not all sources of guidance on Bicillin L‐A administration were identified by the single reviewer. Review of included guidelines was confined to the Bicillin L‐A‐specific section or chapter. This excluded cultural guidance, which may have been provided in other sections of the same or larger guidelines. Finally, guideline review methodology is necessarily reductive; it does not account for the context or relationships associated with BPG injection delivery. It is possible that care delivered by community‐controlled primary care services and Māori and Pacific services is culturally safe, even if this is not specified in the relevant guidelines. Rather, this review focuses on whether guidelines are written as enablers of culturally safe care in all settings.

Conclusion

Bicillin L‐A is a critical drug for Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, with particular importance for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, Māori, and Pacific peoples. Across the features of culturally safe practice, existing clinical guidelines provide consistent information on biomedical knowledge and skills, less information about practising culturally safe behaviours and relatively little guidance on addressing power differentials. Inclusion of enablers of culturally safe care delivery should be considered for future administration guidance development.

Received 26 September 2024; accepted 25 June 2025

Box 2 – Summary of clinical administration guidelines for Bicillin L‐A (Pfizer)

|

Guideline details |

Pain reduction techniques |

Experiential considerations |

|||||||||||||

|

Guideline description (year released) |

Setting |

Finger pressure* |

Local anaesthetic† |

Topical anaesthetic‡ |

Pain device§ |

Distraction¶ |

Rotate site** |

Site preference |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Heart Foundation of New Zealand guideline (2014)28 |

New Zealand |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|||||||

|

Perth Children’s Hospital guideline (2015)29 |

Western Australia |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|||||||

|

RHDAustralia video (2017)30 |

Queensland |

|

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|||||||

|

RHDAustralia and Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia guideline (2018)31 |

South Australia |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|||||||

|

SA Health standing order (2018)32 |

South Australia |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|||||||

|

Kimberley Clinical Protocols guideline (2019)33 |

Western Australia |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|||||||

|

SA Health guideline (2020)34 |

South Australia |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|||||||

|

WA Health training video (2020)35 |

Western Australia |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|||||||

|

RHDAustralia video (2020)36 |

Australia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

SA Health guideline (2020)37 |

South Australia |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|||||||

|

Kimberley Clinical Protocols guideline (2021)38 |

Western Australia |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|||||||

|

RHDAustralia guideline (2022)39 |

Australia |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|||||||

|

Remote Primary Health Care Manuals guideline (2022)40 |

Northern Territory |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|||||||

|

Government of Western Australia, North Metropolitan Health Service guideline (2014)41 |

Western Australia |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

|||||||

|

Royal Flying Doctors Service primary clinical care manual (2022)42 |

Queensland |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|||||||

|

Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine guideline (not specified)43 |

New Zealand |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Te Whatu Ora Health guideline (not specified)44 |

New Zealand |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Total |

|

10 |

12 |

9 |

10 |

9 |

3 |

6 |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Finger pressure on site refers to whether the guideline specified the application of firm pressure to the injection site before or after the injection. † Local anaesthetic refers to whether the guideline specified the inclusion of lidocaine or lignocaine. ‡ Topical anaesthetic refers to whether the guideline specified the inclusion of a cream or spray (eg, Emla cream [which contains lignocaine and prilocaine] or anaesthetic spray). § Pain device refers to whether the guideline specified the inclusion of the Buzzy4Shots vibrating ice pack or a Bionix ShotBlocker. ¶ Distraction refers to whether the guideline indicated the use of electronic video games, wriggling of toes, talking to the patient etc as measures to minimise pain during injection. ** Rotate site refers to whether the guideline specified the rotation of the injection site between scheduled injections. |

|||||||||||||||

- Shriyutha Vaka1

- Lisa J Whop2

- Sophie J Kirk3

- Laurens Manning3

- Rosemary Wyber2,4

- 1 Australian National University, Canberra, ACT

- 2 Yardhura Walani, National Centre for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Wellbeing Research, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT

- 3 University of Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 4 The Kids Research Institute Australia, Perth, WA

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Australian National University, as part of the Wiley – Australian National University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

No specific funding was provided for this study. Rosemary Wyber and Lisa Whop are supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grants (2025252 and 2009380, respectively). Laurens Manning is supported by a Medical Research Future Fund Fellowship (APP1197177). Funding agencies had no role in the design or interpretation of this research.

Lisa Whop is a member of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Strategy Group of the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency.

Authors’ contributions:

Vaka S: Data curation, formal analysis, project administration, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Whop LJ: Formal analysis, writing – review and editing, cultural leadership. Kirk SJ: Validation. Manning L: Conceptualization, supervision, writing – review and editing. Wyber R: Conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

- 1. RHD Action. Global status of BPG report: the benzathine penicillin G report. https://rhdaction.org/sites/default/files/RHD%20Action_Global%20Status%20of%20BPG%20Report_Online%20Version.pdf (viewed Oct 2023).

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia. Canberra: AIHW, 2024. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous‐australians/arf‐rhd/contents/summary (viewed Feb 2024).

- 3. Institute of Environmental Science and Research. Rheumatic fever cases in 2023. New Zealand: ESR, 2023.

- 4. Australian Centre for Disease Control. National syphilis surveillance quarterly report. Quarter 2: 1 April – 30 June 2024. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care, 2024. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national‐syphilis‐surveillance‐quarterly‐report‐april‐to‐june‐2024?language=en (viewed Feb 2024).

- 5. Public Health Agency – Te Pou Hauora Tūmatanui. Aide‐Mémoire: update on infectious and congenital syphilis. Wellington: Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora, 2024. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/2024‐08/h2024036479_update_on_infectious_and_congenital_syphilis_black_box.pdf (viewed Aug 2025).

- 6. Dick D on behalf of Calma T. Social determinants and the health of Indigenous peoples in Australia — a human rights based approach. International Symposium on the Social Determinants of Indigenous Health; Adelaide (Australia); 29–30 Apr 2007. https://humanrights.gov.au/about/news/speeches/social‐determinants‐and‐health‐indigenous‐peoples‐australia (viewed Aug 2025).

- 7. Wyber R, Wade V, Anderson A, et al. Rheumatic heart disease in Indigenous young peoples. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2021; 5: 437‐446.

- 8. Tarrago A, Veit‐Prince E, Brolan CE. “Simply put: systems failed”: lessons from the Coroner’s inquest into the rheumatic heart disease Doomadgee cluster. Med J Aust 2024; 221: 13‐16. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2024/221/1/simply‐put‐systems‐failed‐lessons‐coroners‐inquest‐rheumatic‐heart‐disease

- 9. Ilievski J, Mirams O, Trowman R, et al. Patient preferences for prophylactic regimens requiring regular injections in children and adolescents: a systematic review and thematic analysis. BMJ Paediatr Open 2024; 8: e002450.

- 10. Bimerew M, Araya FG, Ayalneh M. Adherence to secondary antibiotic prophylaxis among patients with acute rheumatic fever and/or rheumatic heart disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ Open 2024; 14: e082191.

- 11. Kevat PM, Reeves BM, Ruben AR, Gunnarsson R. Adherence to secondary prophylaxis for acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: a systematic review. Curr Cardiol Rev 2017; 13: 155‐166.

- 12. Tobin R, Roberts M, Phoo NNN, et al. Factors influencing adult and adolescent completion of treatment for late syphilis: a mixed methods systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 2025; 103: 316‐327E.

- 13. Mitchell A, Kelly J, Cook J, et al. Clonidine for pain‐related distress in Aboriginal children on a penicillin regimen to prevent recurrence of rheumatic fever. Rural Remote Health 2020; 20: 5930.

- 14. Barker H, Oetzel JG, Scott N, et al. Enablers and barriers to secondary prophylaxis for rheumatic fever among Māori aged 14–21 in New Zealand: a framework method study. Int J Equity Health 2017; 16: 201.

- 15. Seghers F, Taylor MM, Storey A, et al. Securing the supply of benzathine penicillin: a global perspective on risks and mitigation strategies to prevent future shortages. Int Health 2024; 16: 279‐282.

- 16. Wyber R, Pearson G, Manning L. Shortages of benzathine benzylpenicillin G in Australia highlight the need for new sovereign manufacturing capability. Med J Aust 2025; 222: 223‐225. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2025/222/5/shortages‐benzathine‐benzylpenicillin‐g‐australia‐highlight‐need‐new‐sovereign

- 17. Cooper J, Enkel SL, Moodley D, et al. “Hurts less, lasts longer”; a qualitative study on experiences of young people receiving high‐dose subcutaneous injections of benzathine penicillin G to prevent rheumatic heart disease in New Zealand. PLoS One 2024; 19: e0302493.

- 18. Kado J, Salman S, Hla TK, et al. Subcutaneous infusion of high‐dose benzathine penicillin G is safe, tolerable, and suitable for less‐frequent dosing for rheumatic heart disease secondary prophylaxis: a phase 1 open‐label population pharmacokinetic study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2023; 67: e0096223.

- 19. Bennett J, Salman S, Moodley D, et al. High dose, subcutaneous injections of benzathine penicillin G (SCIP) to prevent rheumatic fever: a single arm, phase IIa trial of safety and pharmacokinetics. J Infect 2025; 91: 106506.

- 20. Mitchell AG, Belton S, Johnston V, et al. Aboriginal children and penicillin injections for rheumatic fever: how much of a problem is injection pain? Aust N Z J Public Health 2018; 42: 46‐51.

- 21. Rondini AC, Kowalsky RH. “First do no harm”: clinical practice guidelines, mesolevel structural racism, and medicine’s epistemological reckoning. Soc Sci Med 2021; 279: 113968.

- 22. Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Strategy. Melbourne: Ahpra, 2023. https://www.ahpra.gov.au/About‐Ahpra/Aboriginal‐and‐Torres‐Strait‐Islander‐Health‐Strategy.aspx (viewed Apr 2024).

- 23. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 467‐473.

- 24. Agree Trust. AGREE II‐Global Rating Scale (AGREE II‐GRS) Instrument. https://www.agreetrust.org/wp‐content/uploads/2013/12/AGREE‐II‐GRS‐Instument.pdf (viewed Apr 2024).

- 25. Muller J, Devine S, Geia L, et al. Audit tools for culturally safe and responsive healthcare practices with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: a scoping review. BMJ Glob Health 2024; 9: e014194.

- 26. Huria T, Palmer SC, Pitama S, et al. Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples: the CONSIDER statement. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019; 19: 173.

- 27. Harrington Z, Thomas DP, Currie BJ, Bulkanhawuy J. Challenging perceptions of non‐compliance with rheumatic fever prophylaxis in a remote Aboriginal community. Med J Aust 2006; 184: 514‐517. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2006/184/10/challenging‐perceptions‐non‐compliance‐rheumatic‐fever‐prophylaxis‐remote

- 28. Heart Foundation of New Zealand. New Zealand guidelines for rheumatic fever: diagnosis, management and secondary prevention of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: 2014 update. Heart Foundation of New Zealand, 2014. https://assets.heartfoundation.org.nz/documents/shop/marketing/non‐stock‐resources/diagnosis‐management‐rheumatic‐fever‐guideline.pdf (viewed Dec 2023).

- 29. Perth Children’s Hospital. Benzathine benzylpenicillin (benzathine penicillin G) monograph ‐ paediatric. Perth: PCH, 2024.

- 30. RHDAustralia. BPG injection sites and methods [video]. 2017. https://youtu.be/BlO_hojT5ik (viewed Jan 2024).

- 31. RHDAustralia. Guide to administering penicillin injections for RF/RHD. RHDAustralia, 2018. https://www.rhdaustralia.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2025/03/guide_to_adminstering_bpg_v5.pdf (viewed Jan 2024).

- 32. SA Health. Model standing drug order: secondary prophylaxis for the prevention of recurrent acute rheumatic fever — benzathine benzylpenicillin G (Bicillin‐LA®). 2024. https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/5981d58046a66cbeacb9feb0ec6dccc9/CDCB_RHD_ModelStandingDrugOrder‐ARF‐BenzathineBenzylpenicillin%28BicillinL‐A%29_June2024.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE‐5981d58046a66cbeacb9feb0ec6dccc9‐pici7uN (viewed Jan 2024).

- 33. Kimberley Clinical Protocols. Skin infections in children. Kimberley Aboriginal Health Planning Forum, 2019. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b5fbd5b9772ae6ed988525c/t/6400446b61e52f057891ea0a/1677739117908/Skin_Infections_In_Children_Kimberley_Clinical_Protocol_KAHPF_endorsed_12122019.pdf (viewed Dec 2023).

- 34. SA Health. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: pain management for long‐acting benzathine benzylpenicillin (Bicillin L‐A®) injections. Information for health professionals. Adelaide: Department for Health and Wellbeing, Government of South Australia, 2020. https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/f43a6660‐2ddf‐4385‐970a‐9be1be672e8e/Final+‐+Pain+management+‐+Fact+Sheet‐Health+Professionals.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE‐f43a6660‐2ddf‐4385‐970a‐9be1be672e8e‐nKPn‐ZB (viewed Sept 2023).

- 35. WA Health. Injection technique for administering benzathine penicillin treatment for syphilis [video]. 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_KLfZU9w1es (viewed Dec 2023).

- 36. RHDAustralia. Primary prevention of ARF and RHD: primary prevention of acute rheumatic fever (ARF). RHDAustralia, 2020.

- 37. SA Health. Rheumatic fever and penicillin injections: how to reduce pain. Information for patients. Adelaide: Department for Health and Wellbeing, Government of South Australia, 2020. https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/4f01a364‐ce30‐44d2‐bf20‐6a1fc1a2a979/Final+‐+How+to+reduce+pain+‐+Fact+Sheet‐Patients.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=ROOTWORKSPACE‐4f01a364‐ce30‐44d2‐bf20‐6a1fc1a2a979‐nKOm0QI (viewed Oct 2023).

- 38. Kimberley Clinical Protocols. Rheumatic heart disease (RHD). Kimberley Aboriginal Health Planning Forum, 2021. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b5fbd5b9772ae6ed988525c/t/643788912f55e91ec450509a/1681361045281/Rheumatic_Heart_Disease_RHD_Kimberley_Clinical_Protocol_KAHPF_published_20012021.pdf (viewed Dec 2023).

- 39. RHDAustralia (ARF/RHD Writing Group). The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease (3.2 edition, March 2022). Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research, 2022.

- 40. Remote Primary Health Care Manuals. Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD). https://www.remotephcmanuals.com.au/content/documents/manuals/rheumatic/Acute_rheumatic_fever_and_rheumatic_heart_disease.html?publicationid=2019‐STM‐website (viewed Oct 2023).

- 41. Government of Western Australia, North Metropolitan Health Service. Adult medication guide: benzathine benzylpenicillin G (BGP) (benzathine penicillin). https://www.wnhs.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/HSPs/NMHS/Hospitals/WNHS/Documents/Clinical‐guidelines/Obs‐Gyn‐MPs/Benzathine‐Penicillin.pdf?thn=0 (viewed Dec 2023).

- 42. Royal Flying Doctor Service – Queensland Section. Primary clinical care manual 11th edition, 2022.

- 43. Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine. Syphilis. https://sti.guidelines.org.au/sexually‐transmissible‐infections/syphilis (viewed Dec 2023).

- 44. Te Whatu Ora: Health New Zealand. Treating a sore throat with a single penicillin injection. https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/assets/For‐the‐health‐sector/Health‐sector‐guidance/Diseases‐and‐conditions/Rheumatic‐fever/English.pdf (viewed Dec 2023).

- 45. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian product information – Bicillin® L‐A (benzathine benzylpenicillin tetrahydrate) suspension for injection. 2024. https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?OpenAgent&id=CP‐2011‐PI‐03383‐3&d=20240129172310101&d=20240518172310101 (viewed Jan 2024).

- 46. Bowen AC, Tong SY, Andrews RM, et al. Short‐course oral co‐trimoxazole versus intramuscular benzathine benzylpenicillin for impetigo in a highly endemic region: an open‐label, randomised, controlled, non‐inferiority trial. Lancet 2014; 384: 2132‐2140.

- 47. Arthur L, Rolan P. A systematic review of western medicine’s understanding of pain experience, expression, assessment, and management for Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Pain Rep 2019; 4: e764.

- 48. Magnusson JE, Fennell JA. Understanding the role of culture in pain: Māori practitioner perspectives relating to the experience of pain. N Z Med 2011; 124: 30‐40.

- 49. Jiamton S, Nokdhes Y‐N, Limphoka P, et al. Reducing the pain of intramuscular benzathine penicillin injection in syphilis by using 1% lidocaine as a diluent: a prospective, randomized, double‐blinded trial study [abstract]. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83 (6 Suppl): AB29.

- 50. Russell K, Nicholson R, Naidu R. Reducing the pain of intramuscular benzathine penicillin injections in the rheumatic fever population of Counties Manukau District Health Board. J Paediatr Child Health 2013; 50: 112‐117.

- 51. Anderson A, Peat B, Ryland J, et al. Mismatches between health service delivery and community expectations in the provision of secondary prophylaxis for rheumatic fever in New Zealand. Aust N Z J Public Health 2019; 43: 294‐299.

- 52. Mincham CM, Toussaint S, Mak DB, Plant AJ. Patient views on the management of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in the Kimberley: a qualitative study. Aust J Rural Health 2003; 11: 260‐265.

- 53. Chamberlain‐Salaun J, Mills J, Kevat PM, et al. Sharing success – understanding barriers and enablers to secondary prophylaxis delivery for rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2016; 16: 166.

Abstract

Objective: This scoping review explores existing clinical guidelines on administration of benzathine benzylpenicillin (Bicillin L‐A, Pfizer Australia) in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. The objective is to understand existing delivery guidance to address variation in care and cultural safety considerations, to support messaging during periods of stockout and to inform planning for new administration techniques.

Data sources: Semi‐structured Google search to identify publicly available clinical resources for each jurisdiction of Australia and for New Zealand. The search was conducted from October to December 2023.

Design: Government reports and publicly available clinical guidelines were included. This scoping review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR).

Results: This guideline review demonstrates that guidance on administration of Bicillin L‐A in Australia and New Zealand has strong, consistent, biomedical recommendations but underdeveloped cultural considerations. Across the features of culturally safe practice, existing clinical guidelines provide consistent information on biomedical knowledge and skills, less information about practising culturally safe behaviours and relatively little guidance on addressing power differentials.

Conclusions: Cultural safety inclusions should be considered for future administration guidance development.