The known: Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD) prevention is a national priority. Legislative reforms, which now require Queensland Hospital and Health Services to collaborate with Indigenous communities to eliminate RHD, necessitate accurate regional burden estimates.

The new: Analysis of linked Queensland administrative data using multiple sources has identified ARF and RHD burden across health service regions and missed opportunities for disease prevention.

The implications: The significant ARF and RHD burden among Indigenous Queenslanders, and vast disparity with non‐Indigenous populations, calls for an urgent whole‐of‐government response to redress. Analysis of linked administrative data can inform place‐based ARF and RHD strategies.

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) and its precursor acute rheumatic fever (ARF) are potent markers of inequity in Australia. Nationally, Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (hereafter respectfully referred to as Indigenous people) aged younger than 55 years are over 60 times more affected by either condition than non‐Indigenous people.1 The National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation is now funded to lead place‐based RHD elimination efforts, recognising the importance of Indigenous self‐determination in effective management of ARF and RHD.2 This partnership commits to Indigenous leadership, reflecting the necessary shift of control to enable the required whole‐of‐government and community effort.3 Under this elimination strategy, new community‐centred service models for prevention have been developed, building on community strengths and allocating resources to strategies that communities know will work.2 Prevention of RHD could save the health system upwards of $188 million in hospitalisations alone while preventing 663 premature deaths before 2031.2,4

Queensland has been recognised as a jurisdiction with a high RHD clinical load and established the RHD Register in 2009. Nevertheless, serious health system failures were identified in the Coroner’s inquest into the RHD Doomadgee cluster where three young Indigenous women died from RHD complications during the period 2019–2020.5 Since the Doomadgee deaths, coordinated statewide and community‐centred prevention and control activities have commenced in response to legislative directives.6,7 Understanding detailed regional ARF and RHD epidemiological burdens within Queensland is critical for informing place‐based prevention and control strategies and monitoring the efficacy of these activities.6 However, estimating ARF and RHD burden accurately is challenging, due to known issues associated with disease diagnosis and notification leading to under‐ascertainment.8 Measurement inaccuracies associated with RHD prevalence can be reduced by using linked administrative health data, as demonstrated by the landmark End RHD in Australia: Study of Epidemiology (ERASE) project.1 Recent mandatory notification requirements in Queensland (since 2018) and the degree of aggregation among national ERASE 2015–2017 estimates highlight the urgent need for updated and regionally disaggregated ARF and RHD epidemiological estimates for Queensland.1,2,6

Consequently, the Queensland End RHD (QERHD) project established a novel collection of linked Queensland administrative datasets to describe the burden of disease, outcomes and health care access related to ARF and RHD in Queensland between 2017 and 2021. We report here the first output of the QERHD project, estimating the incidence and prevalence of ARF and RHD in Queensland stratified by public Hospital and Health Service (hereafter referred to as “health service”) and key demographics to inform regional and statewide elimination activities.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective population‐level study of Queensland ARF and RHD incidence and prevalence used linked longitudinal administrative data. A brief description of the Queensland health system and a detailed description of the establishment the QERHD project data collection and study design are available in the Supporting Information (supplementary materials and methods and figure 1). We report our study in accordance with the Consolidated criteria for strengthening the reporting of health research involving Indigenous peoples (CONSIDER) guidelines9 (Supporting Information, CONSIDER statement).

For the current study, incidence and prevalence of ARF and RHD were calculated overall for Queensland and stratified by health service region and Indigenous status. For incidence calculations (for ages ≤ 44 years), we calculated the age‐specific and age‐standardised incidence of: first ever ARF; total ARF; and RHD. For prevalence (for ages ≤ 54 years), age‐specific and age‐standardised prevalence was calculated for: ARF or RHD (encompassing cases with a history of either condition); RHD; and severe RHD. Study metrics were chosen to enable direct comparisons with previous multijurisdictional Australian estimates.10

Data sources

The QERHD project data collection was assembled from multiple administrative sources that were person‐linked using deterministic and probabilistic methods. The data‐generating cohort included Queensland residents who either had a principal or additional diagnosis of ARF (International classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision, Australian modification [ICD‐10‐AM] I00‐I02) or RHD (ICD‐10‐AM I05‐I09) in public (1 January 2001 to 31 December 2021) or private (1 January 2007 to 31 December 2021) hospitalisation records, or appeared in the Queensland RHD Register (1 January 2009 to 31 December 2021).

The QERHD data collection includes all person‐linked records for this cohort obtained from RHD hospitalisation and RHD Register records, and their corresponding mortality records (1 January 2001 to 31 December 2021), enabling a theoretical lookback period of up to 20 years and 30 years in these data sources, respectively (Supporting Information, figure 1). For hospitalisations and emergency presentation records, person‐linked data were available from 5 years before a person’s record for ARF or RHD in either the RHD Register or hospital data up to 31 December 2021, enabling a lookback period of up to 5 years. We extracted patient demographic information (age, sex, Indigenous status, residential location), dates of admission and discharge, diagnoses from principal and other diagnostic fields, dates and details of procedures, and date of death from underlying cause of death fields, as well as RHD Register‐based variables related to clinical status.

Sample selection and case definitions

People with an ARF episode between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2021 aged ≤ 44 years were selected, as ARF is rare at older ages.10 ARF episodes were identified from RHD Register‐recorded ARF diagnoses or ICD‐10‐AM‐coded ARF principal diagnoses (I00‐I02) in hospitalisation records. First ever ARF episodes were identified using a lookback period for each person to search their records for any previous record of ARF or RHD across all data sources. Episodes were designated “recurrent” when they occurred > 90 days after the previous ARF record. Total ARF episodes represent the sum of first ever and recurrent episodes.

For RHD, prevalent cases were identified in the study period and available lookback period from all data sources and were alive at 1 July 2017. People aged ≥ 55 years were excluded due to the expected large number of false‐positive cases in hospital data. In addition, a predictive algorithm was used to further optimise case identification in hospital data.11 RHD was considered “severe” if this was noted in RHD Register data or if a person had a concomitant diagnosis of heart failure or a procedure code for valvular surgery in hospital data. “Prevalent ARF or RHD” is a composite metric capturing all individuals ever affected by these sequelae of Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A streptococcus) infection and alive at the prevalence date; all such individuals are at risk of ARF recurrence, disease progression and cardiac complications. For RHD incidence calculations, we included all new RHD cases which occurred during the study period, where no prior RHD record was identified from any data source in the lookback period.

Baseline demographic variables

Demographic characteristics for all cohort members included: age, sex, population (Indigenous, immigrant from a low income or middle‐income country, other Queenslander), geographical residence, remoteness, and social disadvantage (Supporting Information, figure 1). For population, a low threshold of “ever” recorded as Indigenous across any data source was adopted when assigning Indigenous status to address systematic under‐reporting in administrative data.12 Non‐Indigenous populations with known higher risk of RHD, including Māori and Pasifika populations, were classified as immigrant from low income or middle‐income country based on ethnicity and country of birth information, in conjunction with World Bank income data.13 All remaining people were categorised as other Queenslander. Geographical residence was based on health service catchment at the time of the earliest ARF episode or RHD record, whichever was earliest. Other area‐level variables included Level 2 statistical areas: Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia,14 an indication of remoteness from health services; and Index of Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage, a measure of socio‐economic deprivation.15 “Sex” refers to the binary classification (male or female) recorded at the time of the health care interaction in administrative data sources and may not necessarily represent gender identity.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics for ARF episodes (1 January 2017 to 31 December 2021) and prevalent RHD cases as at 1 July 2021 were summarised as counts with proportions (categorical) and as means with standard deviations (continuous). To calculate incidence and prevalence, the sums of the annual number of each case type for each year of the study were numerators. Annual denominator estimates were sourced from Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016 census data) population estimates and summed. Age‐specific incidence estimates (for ages 0–44 years) and prevalence estimates (for ages 0–54 years) for ARF and RHD were used with World Health Organization World Standard Population distribution16 to calculate age‐standardised incidence rate, age‐standardised incidence rate ratio, age‐standardised prevalence and age‐standardised prevalence ratio estimates with 95% confidence intervals. These were stratified by Indigenous status, sex and health service. Analyses were conducted in R version 4.2.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Approvals and positionality

The study was approved by the Prince Charles Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/2021/QPCH/79580) and the University of Queensland Research Ethics and Integrity Committee (2021/HE002507), and received Public Health Act 2005 (Qld) approval (PHA79580). Indigenous leadership and governance were embedded by the lead investigator CJF (Saibai Koedal) in consultation with Indigenous health, research and community leaders.

Results

Demographic and clinical profile for ARF

During the period 2017–2021, 736 ARF episodes were recorded among 670 Queenslanders aged ≤ 44 years (mean age, 15.4 years; SD, 9.5 years), of whom 395 were female (54%) (Box 1). Episodes peaked among children aged 5–14 years for both Indigenous and non‐Indigenous populations. Most ARF episodes (609/736; 83%) were experienced by Indigenous people. Of the remaining episodes, 53 (42%) were experienced by immigrants from low income or middle‐income countries. First ever ARF episodes comprised 478 (78%) and 109 (86%) episodes for Indigenous people and non‐Indigenous people, respectively. Most episodes were among the most socially disadvantaged quintile — 344 among Indigenous people (56%) and 47 among non‐Indigenous people (37%) in this group.

Most ARF episodes experienced by Indigenous people were in non‐metropolitan regions, with 480 episodes (79%) across outer regional, remote and very remote Queensland, and 434 episodes (71%) in the three most north‐western health services of Torres and Cape, Cairns and Hinterland and North West (Box 1). Most episodes in non‐Indigenous people (71/127; 56%) occurred in a major city, with 83 episodes (65%) recorded at Metro South, Metro North and West Moreton health services (Box 1).

Demographic and clinical profile for RHD

We identified 4519 Queenslanders with RHD aged < 55 years (mean age, 34.7 years; SD, 13.7 years, Box 2), of whom 2655 (59%) were female. Indigenous people comprised nearly half of all RHD cases (2169/4519; 48%). Among the remaining 2350 RHD cases, in non‐Indigenous people, 665 (28%) were in immigrants from low income or middle‐income countries and 1685 (72%) were in other Queenslanders. Peak RHD prevalence for Indigenous people was at 15–24 years of age, whereas non‐Indigenous prevalence peaked at 45–54 years.

Over one‐quarter of all RHD cases were aged < 25 years (1198/4519; 27%), of whom 790 (66%) were Indigenous. The Queensland RHD Register had been notified of 633 Indigenous people (80%) and 133 non‐Indigenous people (33%) with RHD aged < 25 years (Box 2). Of all 4519 RHD cases, 362 (8%) had a record of ARF before onset of RHD in any data source, 1846 (41%) had severe RHD, and 729 (16%) had a prior cardiac valvular intervention.

Most Indigenous people with RHD lived in outer regional, remote or very remote Queensland (1634/2169; 75%), mostly within the north‐western health services of Torres and Cape, Cairns and Hinterland, North West and Townsville (1768/2169; 82%). In contrast, most non‐Indigenous people with RHD resided in major cities (1372/2350; 58%), mostly within metropolitan Brisbane Metro South and Metro North health services (1085/2350; 46%). The distribution of Indigenous RHD cases was highly skewed towards socially disadvantaged areas, with 1239 (57%) in the lowest quintile, whereas non‐Indigenous cases were more evenly distributed.

Incidence rates for ARF and RHD, 2017–2021

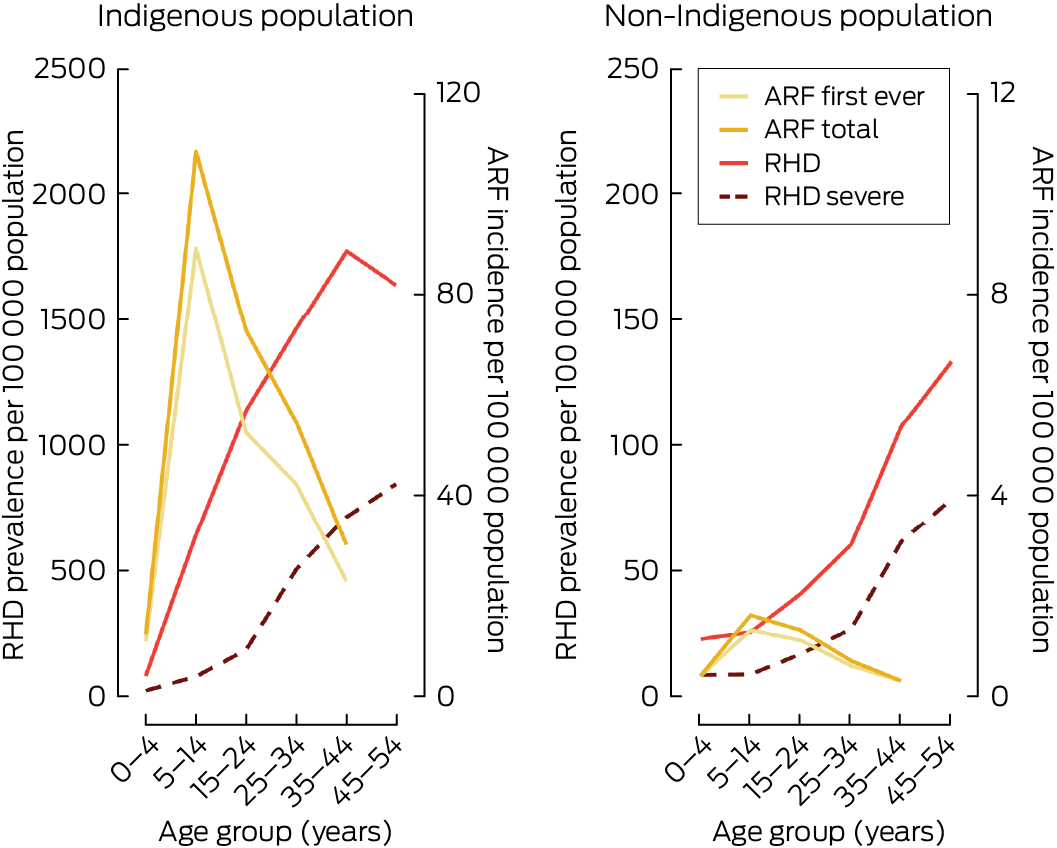

During the period 2017–2021, the age‐specific total incidence of ARF for 0–44‐year‐olds peaked at 5–14 years and steadily declined above 15 years of age (Box 3; Box 4). For first ever ARF, Indigenous age‐specific rates were 27.0 to 76.0 times higher than non‐Indigenous rates. The age‐standardised rates for ages 0–44 years were 48.2 (Indigenous) and 0.8 (non‐Indigenous) for first ever ARF episodes per 100 000 population, with an age‐standardised rate ratio of 60.2 (95% CI, 55.6–64.2). For total ARF, Indigenous age‐specific rates were between 30.5 and 100.3 times higher than non‐Indigenous rates, with age‐standardised rates for ages 0–44 years of 61.7 (Indigenous) and 0.9 (non‐Indigenous) per 100 000 population (age‐standardised rate ratio, 68.6 [95% CI, 62.3–72.5]). Limiting to ages < 25 years reduced the age‐standardised rate ratio for both first ever and total ARF (Box 3).

For new RHD diagnoses (for ages 0–44 years), age‐specific incidence peaked at 34–45 years of age overall (Box 3). Indigenous age‐specific rate differentials peaked at 36.5 times higher than non‐Indigenous rates among 5–14‐year‐olds. The RHD age‐standardised rates were 92.4 (Indigenous) and 4.9 (non‐Indigenous) per 100 000 population (age‐standardised rate ratio, 18.9 [95% CI, 13.5–24.1]). Limiting to ages < 25 years did not substantially alter the age‐standardised rate ratio.

Mean annual prevalence of ARF and RHD, 2017–2021

The mean annual number of prevalent ARF or RHD cases aged < 55 years was 5434 people (Box 5). Peak prevalence was at 35–45 years for the Indigenous population and at 45–54 years for the non‐Indigenous population (Box 5). Following age standardisation, Indigenous people < 55 years of age were 22.6 times (95% CI, 16.2–27.3) more likely to have a history of ARF or RHD than non‐Indigenous people, which increased to 31.7 times (95% CI, 26.7–35.8) when limited to ages < 25 years.

The mean annual number of prevalent RHD cases aged < 55 years was 4634 people, of which 1935 were severe (Box 5). For Indigenous people, age‐specific prevalence peaked at 35–44 years followed by a decline from 45 years, whereas non‐Indigenous RHD prevalence steadily increased with age (Box 5; Box 4). After age standardisation, the RHD prevalence for the Indigenous population aged < 55 years (1160 people per 100 000) was 18.4 times higher (95% CI, 12.9–24.1) than that of the non‐Indigenous population (62.9 people per 100 000), which increased to 23.5 times higher (95% CI, 16.2–29.6) when limited to ages < 25 years (Box 5).

Overall, the age‐specific prevalence of severe RHD cases aged < 55 years steadily increased with age, but the age‐standardised prevalence ratio peaked at 25–34 years (19.0 [95% CI, 17.3–22.2]) (Box 5; Box 4). Age standardisation showed that the prevalence of severe RHD in the Indigenous population aged < 55 years (384.4 people per 100 000) was 12.1 times higher (95% CI, 8.3–15.9) than that of the non‐Indigenous population (31.8 people per 100 000), which reduced when limited to ages < 25 years.

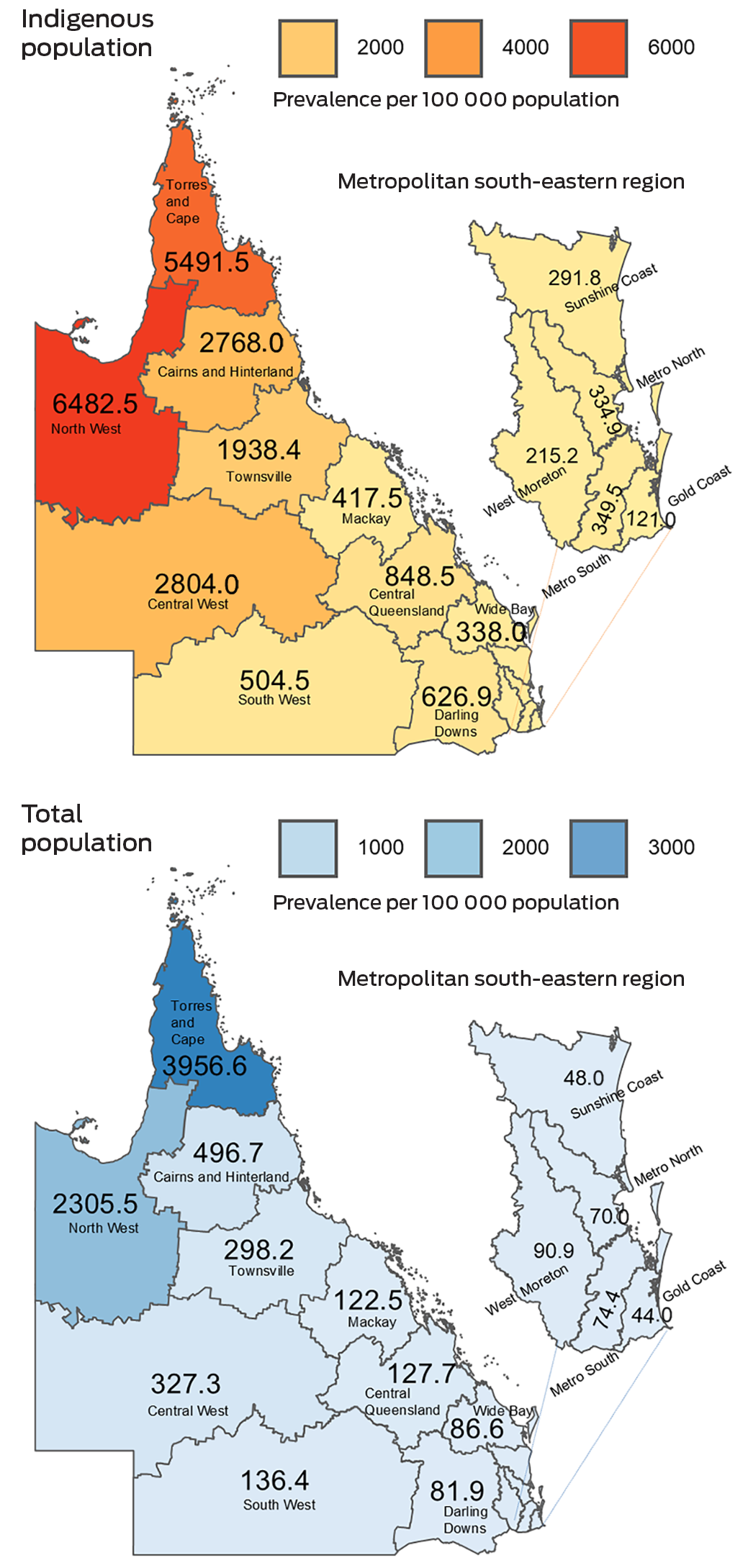

Geographical place of residence and sex distribution

Box 6 shows the geographical distribution of age‐standardised ARF or RHD prevalence in Queensland, by health service. For all regions, the prevalence was substantially higher for Indigenous residents compared with the total health service populations. The highest estimates for prevalence of ARF or RHD were among Indigenous populations of the North West (6482.5 people per 100 000) and Torres and Cape (5491.5 people per 100 000) health services. Of the metropolitan south‐eastern regions, the highest estimates of ARF or RHD prevalence were in the West Morton (total population, 90.9 people per 100 000) and Metro South (Indigenous population, 349.5 people per 100 000) health services. Geographical distribution of prevalent RHD shows a similar pattern (Supporting Information, figure 2 and figure 3). Overall, female participants experienced a greater burden of ARF and RHD than male participants (Box 1 and Box 2); this sex differential was most pronounced among Indigenous people (Supporting Information, figure 4).

Discussion

We collated multiple linked data sources to provide the most contemporary profile of ARF and RHD epidemiology in Queensland, showing Indigenous Queenslanders to be among the most impacted populations among high income countries with universal health care.17 Three‐quarters of Queensland ARF episodes occurred in people younger than 25 years, with the highest burden among Indigenous children aged 5–14 years, 67.9 times higher than among their non‐Indigenous counterparts. Over‐representation of new RHD diagnoses among Indigenous Queenslanders peaked at ages 5–14 years (94.9 children/100 000) at rates that were 36.5 times higher than those for their non‐Indigenous counterparts. RHD prevalence at ages < 55 years was 18.4 times higher in the Indigenous population, and comparable with other northern Australian jurisdictions with high RHD burden.1 The highest prevalence of ARF or RHD was distributed among the four most remote north‐western health services.

The prevalence of ARF or RHD among Indigenous Queenslanders younger than 55 years of 1388 people per 100 000 represents a steep increase from the 2015–2017 ERASE estimate of 862.1 per 100 000.1 In Queensland, higher reporting resulting from improved disease awareness, the introduction of notification for RHD in 2018 and specialist outreach activity, particularly in northern regions, may partly explain this increase.18 An encouraging finding was that 80% of young Indigenous people (aged < 25 years) with RHD were known to the Queensland RHD control program, which plays a critical support role for primary care services in the delivery of secondary prevention.

Our study builds on previous reports of the iniquitous disease burden concentrated among Australian Indigenous populations.1 The overall ARF and RHD disparity for Indigenous compared with non‐Indigenous Queenslanders (22.6 times more likely to be affected), while vast, was notably smaller than the national ERASE estimate (61.4 times).1 This difference is likely explained by the high proportion of Queensland non‐Indigenous RHD cases (52%) relative to ERASE (29%).

It is possible that the lack of primary care data as a source of ARF and RHD diagnosis information may have excluded milder cases from our study cohort, leading to underestimation; however, this was partly mitigated by the inclusion of RHD Register data, with good coverage of younger people who had less severe disease.19 Nonetheless, our ARF data should be interpreted with caution due to comparatively poor case capture for ARF, which reflects known difficulty in diagnosis, with additional historical underdiagnosis and under‐reporting;20 patients with RHD often present without a prior record of ARF.1 Recent evidence of missed opportunities to detect ARF and RHD in hospital admissions,8,21,22 together with the high proportion of severe RHD we report among the non‐Indigenous population (few with a prior ARF record), highlights the need for enhanced clinical suspicion of ARF and awareness of environmental and other risk factors driving ARF and RHD. Limited clinician awareness, especially in metropolitan areas, may also have contributed to late diagnosis and under‐reporting of RHD by some hospitals, as a substantial proportion (67%) of young non‐Indigenous individuals first diagnosed with RHD in hospital were not recorded on the RHD Register. Population data on non‐Indigenous subpopulations are not collected, limiting disaggregated estimates for non‐Indigenous populations. Our use of country of birth as a proxy for high risk status among non‐Indigenous people does not capture higher risk children of migrants born in Australia, further limiting our analysis of this group.

A strength of our study is the application of rigorous ERASE methods, including a predictive algorithm to adjust for systemic overestimation of RHD hospitalisations due to coding conventions, where certain valve lesions default to RHD.11 We have addressed the known under‐reporting of ARF and RHD cases to the RHD Register and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare routine reporting by supplementing RHD Register data with hospital records,19,22 although a recent multijurisdiction capture–recapture analysis identified that hospital and RHD Register sources likely miss many ARF and RHD cases (mainly undiagnosed), including among non‐Indigenous people.21

Our findings highlight the need for continued investment in and expansion of strategies to prevent childhood S. pyogenes infections to eliminate RHD in Queensland, particularly in north‐western regions and among Indigenous youth. New innovative strategies are being developed to improve primary prevention (environmental interventions23 and S. pyogenes vaccine development24) and secondary prophylaxis (alternative methods of benzathine benzylpenicillin administration25), which can reduce the impact of the disease in the future. A focus on prevention of childhood S. pyogenes infection in Ending Rheumatic Heart Disease: Queensland First Nations Strategy 2021–20246 has meant expanding local capacity for place‐based ARF and RHD activities, including an emphasis on Indigenous health and environmental workforce to lead program coordination, health promotion and community development activities.6 Our results will assist with future evaluation of these efforts on ARF and RHD disease burden, by providing a baseline. Indeed, since implementation, there has been a promising downward trend in ARF and RHD incidence reported by some health services.6

Conclusion

Our findings illustrate the uniqueness of Queensland from a demographic and epidemiological perspective, warranting tailored place‐based programs that prevent and manage ARF and RHD, particularly in high‐burden Indigenous settings. The high number of non‐Indigenous ARF and RHD cases, particularly among young people who were not notified to the RHD Register, highlights the need for enhanced clinical awareness and reporting for this group who are often from immigrant, urban families. Timely access to disaggregated, and potentially linked, administrative data is needed to enable regional health services to implement and evaluate their own ARF and RHD control programs across Queensland. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s new National Health Data Hub (https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports‐data/nhdh), augmented by linked RHD Register data, can potentially provide regular information for jurisdictional planning and monitoring.

Box 1 – Demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals experiencing episodes of acute rheumatic fever by Indigenous status in Queensland, Australia, 2017 – 2021*

|

|

Total |

Indigenous |

Non‐Indigenous |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Individual people, number (% of total cohort) |

670 (100%) |

554 (83%) |

116 (17%) |

||||||||||||

|

Mean age in years (SD) |

15.4 (9.5) |

15.0 (9.3) |

17.2 (10.2) |

||||||||||||

|

Record in RHD Register,† number (% of episodes within ethnicity category) |

643 (87%) |

542 (89%) |

101 (80%) |

||||||||||||

|

Acute rheumatic fever episodes |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Both first ever and recurrent, number (% of all episodes) |

736 (100%) |

609 (83%) |

127 (17%) |

||||||||||||

|

First ever, number (% of episodes within ethnicity category) |

587 (80%) |

478 (78%) |

109 (86%) |

||||||||||||

|

Recurrent, number (% of episodes within ethnicity category) |

149 (20%) |

131 (22%) |

18 (14%) |

||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Female, number (% of episodes within ethnicity category) |

395 (54%) |

337 (55%) |

58 (46%) |

||||||||||||

|

Age group (years), number (% of episodes within ethnicity category) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

0–4 |

22 (3%) |

17 (3%) |

5 (4%) |

||||||||||||

|

5–14 |

341 (46%) |

293 (48%) |

48 (38%) |

||||||||||||

|

15–24 |

209 (28%) |

169 (28%) |

40 (31%) |

||||||||||||

|

25–34 |

117 (16%) |

93 (15%) |

24 (19%) |

||||||||||||

|

35–44 |

47 (6%) |

37 (6%) |

10 (8%) |

||||||||||||

|

Population category, number (% of episodes within ethnicity category) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Indigenous |

609 (83%) |

609 (100%) |

0 |

||||||||||||

|

Immigrant from low income or middle‐income country |

53 (7%) |

0 |

53 (42%) |

||||||||||||

|

Other Queenslander |

74 (10%) |

0 |

74 (58%) |

||||||||||||

|

Hospital and Health Service, number (% of episodes within ethnicity category) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Torres and Cape |

182 (25%) |

180 (30%) |

< 5 |

||||||||||||

|

Cairns and Hinterland |

165 (22%) |

153 (25%) |

12 (9%) |

||||||||||||

|

North West |

108 (15%) |

101 (17%) |

7 (6%) |

||||||||||||

|

Townsville |

89 (12%) |

82 (13%) |

7 (6%) |

||||||||||||

|

Metro South (Brisbane) |

70 (10%) |

16 (3%) |

54 (43%) |

||||||||||||

|

Other‡ |

36 (5%) |

31 (5%) |

5 (4%) |

||||||||||||

|

Metro North (Brisbane) |

30 (4%) |

17 (3%) |

13 (10%) |

||||||||||||

|

Central Queensland |

23 (3%) |

21 (3%) |

< 5 |

||||||||||||

|

West Moreton |

20 (3%) |

< 5 |

16 (13%) |

||||||||||||

|

Mackay |

7 (1%) |

< 5 |

< 5 |

||||||||||||

|

Gold Coast |

(1%) |

< 5 |

5 (4%) |

||||||||||||

|

Socio‐economic disadvantage score, number (% of episodes within ethnicity category) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

1–20 (most disadvantaged) |

391 (53%) |

344 (56%) |

47 (37%) |

||||||||||||

|

21–40 |

145 (20%) |

122 (20%) |

23 (18%) |

||||||||||||

|

41–60 |

62 (8%) |

36 (6%) |

26 (20%) |

||||||||||||

|

61–80 |

30 (4%) |

20 (3%) |

10 (8%) |

||||||||||||

|

81–100 |

11 (1%) |

5 (1%) |

6 (5%) |

||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

97 (13%) |

82 (13%) |

15 (12%) |

||||||||||||

|

Remoteness category, number (% of episodes within ethnicity category) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Very remote |

169 (23%) |

167 (27%) |

< 5 |

||||||||||||

|

Remote |

104 (14%) |

98 (16%) |

6 (5%) |

||||||||||||

|

Outer regional |

234 (32%) |

215 (35%) |

19 (15%) |

||||||||||||

|

Inner regional |

32 (4%) |

18 (3%) |

14 (11%) |

||||||||||||

|

Major city |

100 (14%) |

29 (5%) |

71 (56%) |

||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

97 (13%) |

81 (13%) |

15 (12%) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

RHD = rheumatic heart disease; SD = standard deviation. * Percentages for cells with fewer than 5 individuals are not shown to preserve patient anonymity. † Queensland RHD Control Program and RHD Register. ‡ Other Hospital and Health Services include Sunshine Coast, Central West, South West, Wide Bay and Darling Downs. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals younger than 55 years with rheumatic heart disease who were alive on 1 July 2021, by Indigenous status in Queensland, Australia

|

|

Total |

Indigenous |

Non‐Indigenous |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Total number of cases, number (% of total cases) |

4519 (100%) |

2169 (48%) |

2350 (52%) |

||||||||||||

|

Mean age in years (SD) |

34.7 (13.7) |

30.9 (13.1) |

38.3 (13.2) |

||||||||||||

|

Record in RHD Register,* number/total of those aged < 25 years (%) |

766/1198 (64%) |

633/790 (80%) |

133/408 (33%) |

||||||||||||

|

Age group (years), number (% of total cases) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

0–4 |

46 (1%) |

7 (< 1%) |

39 (2%) |

||||||||||||

|

5–14 |

393 (9%) |

264 (12%) |

129 (5%) |

||||||||||||

|

15–24 |

759 (17%) |

519 (24%) |

240 (10%) |

||||||||||||

|

25–34 |

847 (19%) |

506 (23%) |

341 (15%) |

||||||||||||

|

35–44 |

1026 (23%) |

427 (20%) |

599 (25%) |

||||||||||||

|

45–54 |

1448 (32%) |

446 (21%) |

1002 (43%) |

||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Female, number (% of total cases) |

2655 (59%) |

1356 (63%) |

1299 (55%) |

||||||||||||

|

Socio‐economic disadvantage score, number (% of total cases) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

1–20 (most disadvantaged) |

1852 (41%) |

1239 (57%) |

613 (26%) |

||||||||||||

|

21–40 |

897 (20%) |

413 (19%) |

484 (21%) |

||||||||||||

|

41–60 |

547 (12%) |

136 (6%) |

411 (17%) |

||||||||||||

|

61–80 |

439 (10%) |

80 (4%) |

359 (15%) |

||||||||||||

|

81–100 |

370 (8%) |

13 (1%) |

357 (15%) |

||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

414 (9%) |

288 (13%) |

126 (5%) |

||||||||||||

|

Remoteness category, number (% of total cases) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Very remote |

622 (14%) |

602 (28%) |

20 (1%) |

||||||||||||

|

Remote |

395 (9%) |

349 (16%) |

46 (2%) |

||||||||||||

|

Outer regional |

1058 (23%) |

683 (31%) |

375 (16%) |

||||||||||||

|

Inner regional |

524 (12%) |

119 (5%) |

405 (17%) |

||||||||||||

|

Major city |

1499 (33%) |

127 (6%) |

1372 (58%) |

||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

421 (9%) |

289 (13%) |

132 (6%) |

||||||||||||

|

Population category, number (% of total cases) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Indigenous |

2169 (48%) |

2169 (100%) |

0 |

||||||||||||

|

Immigrant from low income or middle‐income country |

665 (15%) |

0 |

665 (28%) |

||||||||||||

|

Other Queenslander |

1685 (37%) |

0 |

1685 (72%) |

||||||||||||

|

Hospital and Health Service, number (% of total cases) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Cairns and Hinterland |

675 (15%) |

520 (24%) |

155 (7%) |

||||||||||||

|

Metro South |

643 (14%) |

70 (3%) |

573 (24%) |

||||||||||||

|

Torres and Cape |

572 (13%) |

555 (26%) |

17 (1%) |

||||||||||||

|

Metro North |

569 (13%) |

57 (3%) |

512 (22%) |

||||||||||||

|

North West |

440 (10%) |

405 (19%) |

35 (1%) |

||||||||||||

|

Townsville |

434 (10%) |

288 (13%) |

146 (6%) |

||||||||||||

|

Other† |

293 (6%) |

109 (5%) |

184 (8%) |

||||||||||||

|

Gold Coast |

208 (5%) |

8 (< 1%) |

200 (9%) |

||||||||||||

|

West Moreton |

194 (4%) |

22 (1%) |

172 (7%) |

||||||||||||

|

Central Queensland |

189 (4%) |

87 (4%) |

102 (4%) |

||||||||||||

|

Mackay |

156 (3%) |

28 (1%) |

128 (5%) |

||||||||||||

|

Sunshine Coast |

146 (3%) |

20 (1%) |

126 (5%) |

||||||||||||

|

Clinical history, number (% of total cases) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Record of acute rheumatic fever |

362 (8%) |

303 (14%) |

59 (3%) |

||||||||||||

|

Record of severe rheumatic heart disease |

1846 (41%) |

640 (30%) |

1206 (51%) |

||||||||||||

|

Record of cardiac valve surgery |

729 (16%) |

193 (9%) |

536 (23%) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

RHD = rheumatic heart disease; SD = standard deviation. * Queensland RHD Control Program and RHD Register. † Other Hospital and Health Services include Central West, South West, Wide Bay and Darling Downs. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Crude, age‐specific and age‐standardised incidence per 100 000 people for acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease, by Indigenous status, 2017 to 2021

|

|

Total |

Indigenous |

Non‐Indigenous |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

n* |

Per 100 000 (95% CI) |

n* |

Per 100 000 (95% CI) |

n* |

Per 100 000 (95% CI) |

Rate ratio (95% CI) |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

First ever episode of acute rheumatic fever |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

0–4 |

20 |

1.3 (0.7–1.9) |

15 |

10.8 (5.3–16.3) |

5 |

0.4 (0.0–0.7) |

27.0 (25.1–28.9) |

||||||||

|

5–14 |

281 |

8.4 (7.4–9.3) |

241 |

89.3 (78.0–100.6) |

40 |

1.3 (0.9–1.7) |

68.7 (66.4–69.3) |

||||||||

|

15–24 |

156 |

4.8 (4.0–5.5) |

122 |

52.5 (43.2–61.9) |

34 |

1.1 (0.7–1.5) |

47.7 (45.2–49.1) |

||||||||

|

25–34 |

92 |

2.6 (2.0–3.1) |

72 |

42.3 (32.6–52.1) |

20 |

0.6 (0.3–0.8) |

70.5 (68.9–71.7) |

||||||||

|

35–44 |

38 |

1.1 (0.8–1.5) |

28 |

22.8 (14.4–31.3) |

10 |

0.3 (0.1–0.5) |

76.0 (74.3–78.2) |

||||||||

|

0–44 (crude) |

587 |

3.9 (3.6–4.2) |

592 |

49.0 (45.0–52.9) |

133 |

0.8 (0.6–0.9) |

NA |

||||||||

|

Age‐standardised rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

0–24 |

NA |

5.5 (5.0–6.0) |

NA |

58.7 (52.8–64.6) |

NA |

1.0 (0.8–1.3) |

58.7 (54.3–61.4) |

||||||||

|

0–44 |

NA |

4.1 (3.7–4.4) |

NA |

48.2 (43.8–52.5) |

NA |

0.8 (0.6–0.9) |

60.2 (55.6–64.2) |

||||||||

|

Total acute rheumatic fever episodes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

0–4 |

22 |

1.4 (0.8–2.0) |

17 |

12.2 (6.4–18.1) |

5 |

0.4 (0.0–0.7) |

30.5 (28.5–33.1) |

||||||||

|

5–14 |

341 |

10.2 (9.1–11.2) |

293 |

108.6 (96.2–121.0) |

48 |

1.6 (1.1–2.0) |

67.9 (65.8–69.2) |

||||||||

|

15–24 |

209 |

6.4 (5.5–7.3) |

169 |

72.8 (61.8–83.8) |

40 |

1.3 (0.9–1.7) |

56.0 (54.6–58.9) |

||||||||

|

25–34 |

117 |

3.3 (2.7–3.9) |

93 |

54.7 (43.6–65.8) |

24 |

0.7 (0.4–1.0) |

78.1 (76.2–80.2) |

||||||||

|

35–44 |

47 |

1.4 (1.0–1.8) |

37 |

30.1 (20.4–39.9) |

10 |

0.3 (0.1–0.5) |

100.3 (98.2–101.7) |

||||||||

|

0–44 (crude) |

736 |

4.9 (4.5–5.2) |

609 |

60.9 (56.5–65.3) |

127 |

0.9 (0.8–1.0) |

NA |

||||||||

|

Age‐standardised rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

0–24 |

NA |

6.9 (6.3–7.5) |

NA |

74.7 (68.0–81.3) |

NA |

1.2 (1.0–1.5) |

62.3 (59.1–65.9) |

||||||||

|

0–44 |

NA |

5.1 (4.7–5.4) |

NA |

61.7 (56.7–66.6) |

NA |

0.9 (0.8–1.1) |

68.6 (62.3–72.5) |

||||||||

|

Rheumatic heart disease |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

0–4 |

71 |

4.6 (3.5–5.6) |

10 |

7.2 (2.7–11.7) |

61 |

4.3 (3.2–5.4) |

1.7 (1.0–2.3) |

||||||||

|

5–14 |

337 |

10.0 (9.0–11.1) |

256 |

94.9 (83.3–106.5) |

81 |

2.6 (2.1–3.2) |

36.5 (34.8–38.4) |

||||||||

|

15–24 |

296 |

9.0 (8.0–10.1) |

192 |

82.7 (71.0–94.4) |

104 |

3.4 (2.8–4.1) |

24.3 (22.7–26.1) |

||||||||

|

25–34 |

373 |

10.4 (9.4–11.5) |

193 |

113.5 (97.5–129.5) |

180 |

5.3 (4.5–6.1) |

21.4 (19.1–23.9) |

||||||||

|

35–44 |

465 |

13.9 (12.6–15.1) |

163 |

132.8 (112.4–153.2) |

302 |

9.4 (8.3–10.4) |

14.1 (12.5–16.2) |

||||||||

|

0–44 (crude) |

1542 |

10.2 (9.7–10.7) |

922 |

76.3 (71.4–81.2) |

826 |

4.8 (4.5–5.2) |

NA |

||||||||

|

Age‐standardised rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

0–24 |

NA |

8.6 (7.9–9.2) |

NA |

71.8 (65.2–78.3) |

NA |

3.3 (2.9–3.7) |

21.8 (18.3–23.6) |

||||||||

|

0–44 |

NA |

10.0 (9.5–10.5) |

NA |

92.4 (85.9–98.9) |

NA |

4.9 (4.5–5.2) |

18.9 (13.5–24.1) |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval; NA = not applicable. * Sum of cases 2017–2021. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Age‐specific incidence of acute rheumatic fever (at < 45 years of age) and rheumatic heart disease (at < 55 years of age) for the Indigenous and non‐Indigenous populations in Queensland, by age group, 2017–2021*

ARF = acute rheumatic fever. RHD = rheumatic heart disease. * Note the 10‐fold y‐axis scale difference between the Indigenous and non‐Indigenous plots.

Box 5 – Mean annual crude, age‐specific and age‐standardised prevalence per 100 000 people with a history of acute rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, and severe rheumatic heart disease, by Indigenous status, 2017 to 2021

|

|

Total |

Indigenous |

Non‐Indigenous |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

n* |

Per 100 000 (95% CI) |

n* |

Per 100 000 (95% CI) |

n* |

Per 100 000 (95% CI) |

Prevalence ratio (95% CI) |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Acute rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease † |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

0–4 years |

102 |

32.8 (30.0–35.7) |

36 |

129.7 (110.8–148.6) |

66 |

23.3 (20.8–25.9) |

5.6 (4.1–6.9) |

||||||||

|

5–14 years |

721 |

107.4 (103.9–110.9) |

548 |

1015 (977.7–1053) |

173 |

28.0 (26.2–29.9) |

36.3 (34.2–38.7) |

||||||||

|

15–24 years |

1061 |

162.2 (157.9–166.6) |

776 |

1672 (1619–1724) |

285 |

46.9 (44.5–49.3) |

35.7 (33.2–39.1) |

||||||||

|

25–34 years |

1093 |

152.9 (148.8–156.9) |

660 |

1939 (1873–2004) |

433 |

63.6 (60.9–66.3) |

30.5 (28.6–33.4) |

||||||||

|

35–44 years |

1199 |

179.0 (174.5–183.6) |

488 |

1988 (1910–2066) |

711 |

110.2 (106.6–113.8) |

18.0 (15.8–21.1) |

||||||||

|

45–54 years |

1258 |

189.6 (184.9–194.3) |

402 |

1756 (1680–1832) |

856 |

133.5 (129.5–137.5) |

13.2 (11.8–16.2) |

||||||||

|

0–54 years (crude) |

5434 |

147.5 (145.7–149.3) |

2911 |

1388 (1366–1410) |

2524 |

72.6 (71.4–73.9) |

NA |

||||||||

|

Age‐standardised prevalence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

0–24 years |

NA |

113.4 (111.2–115.6) |

NA |

1090 (1036–1144) |

NA |

34.4 (31.5–37.3) |

31.7 (26.7–35.8) |

||||||||

|

0–54 years |

NA |

142.0 (139.5–144.5) |

NA |

1488 (1410–1566) |

NA |

65.8 (62–69.6) |

22.6 (16.2–27.3) |

||||||||

|

Rheumatic heart disease |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

0–4 years |

86 |

27.6 (25.0–30.2) |

22 |

79.3 (64.5–94.1) |

64 |

22.5 (20.0–25.0) |

3.5 (2.1–5.2) |

||||||||

|

5–14 years |

503 |

74.9 (71.9–77.8) |

347 |

642.3 (612.2–672.5) |

156 |

25.3 (23.5–27.0) |

25.4 (22.3–27.8) |

||||||||

|

15–24 years |

777 |

118.8 (115.1–122.5) |

530 |

1140 (1097–1183) |

248 |

40.7 (38.5–43.0) |

28.0 (26.5–30.4) |

||||||||

|

25–34 years |

908 |

127.1 (123.4–130.8) |

498 |

1464 (1407–1521) |

410 |

60.3 (57.7–62.9) |

24.3 (21.1–26.2) |

||||||||

|

35–44 years |

1131 |

168.8 (164.4–173.2) |

436 |

1775 (1701–1849) |

695 |

107.7 (104.1–111.3) |

16.5 (13.3–19.5) |

||||||||

|

45–54 years |

1229 |

185.3 (180.6–189.9) |

376 |

1639 (1566–1713) |

854 |

133.3 (129.3–137.3) |

12.3 (9.6–15.7) |

||||||||

|

0–54 years (crude) |

4634 |

125.8 (124.2–127.4) |

2208 |

1053 (1033–1072) |

2426 |

69.8 (68.6–71.1) |

NA |

||||||||

|

Age‐standardised prevalence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

0–24 years |

NA |

82.3 (80.4–84.2) |

NA |

721.1 (677.3–764.9) |

NA |

30.7 (27.9–33.5) |

23.5 (16.2–29.6) |

||||||||

|

0–54 years |

NA |

118.9 (116.7–121.2) |

NA |

1160 (1091–1229) |

NA |

62.9 (59.2–66.6) |

18.4 (12.9–24.1) |

||||||||

|

Severe rheumatic heart disease |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

0–4 years |

30 |

9.6 (8.1–11.1) |

6 |

21.6 (13.9–29.4) |

24 |

8.4 (6.9–9.9) |

2.6 (1.2–4.5) |

||||||||

|

5–14 years |

95 |

14.1 (12.9–15.4) |

42 |

77.8 (67.3–88.4) |

53 |

8.6 (7.5–9.6) |

9.0 (6.7–12.1) |

||||||||

|

15–24 years |

187 |

28.6 (26.7–30.4) |

85 |

183.5 (166.1–200.9) |

102 |

16.7 (15.3–18.2) |

11.0 (8.9–13.2) |

||||||||

|

25–34 years |

353 |

49.3 (47.0–51.6) |

172 |

505.1 (471.4–538.8) |

181 |

26.6 (24.8–28.3) |

19.0 (17.3–22.2) |

||||||||

|

35–44 years |

572 |

85.5 (82.3–88.6) |

176 |

716.1 (668.9–763.2) |

397 |

61.5 (58.8–64.2) |

11.6 (9.5–14.1) |

||||||||

|

45–54 years |

698 |

105.2 (101.7–108.7) |

194 |

846.9 (793.8–899.9) |

504 |

78.7 (75.6–81.7) |

10.8 (8.3–12.9) |

||||||||

|

0–54 years (crude) |

1935 |

52.5 (51.5–53.6) |

675 |

321.9 (311.1–332.8) |

1260 |

36.3 (35.4–37.2) |

NA |

||||||||

|

Age‐standardised prevalence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

0–24 years |

NA |

18.8 (17.8–19.7) |

NA |

108.4 (91.3–125.5) |

NA |

11.7 (10.0–13.4) |

9.3 (6.6–13.8) |

||||||||

|

0–54 years |

NA |

47.2 (45.9–48.6) |

NA |

384.4 (345.5–423.2) |

NA |

31.8 (29.2–34.3) |

12.1 (8.3–15.9) |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval; NA = not applicable. * Mean annual number of cases 2017–2021. † People with a history of either of condition. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 24 December 2024, accepted 27 May 2025

- Carl J Francia (Saibai Koedal awgadhalayg, Guda Maluylgal Nation)1

- Leanne M Johnston2

- Ingrid Stacey3,4

- Robert N Justo2

- John F Fraser1,5

- Judith M Katzenellenbogen4,6

- 1 University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

- 2 Queensland Children’s Hospital, Brisbane, QLD

- 3 Cardiovascular Epidemiology Research Centre, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 4 University of Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 5 Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, QLD

- 6 Kids Research Institute Australia, Perth, WA

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley – The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Data Sharing:

Queensland End RHD project data are not available to other researchers due to the stringent ethics requirements for using linked data and Indigenous data sovereignty processes. Authors can be approached to collaborate on research to address new research questions using this database.

A Prince Charles Hospital Foundation Common Good New Investigator Grant (NI203‐11) funded time off from clinical responsibilities for Carl Francia to devote to data management and analysis.

No relevant disclosures.

Authors’ contributions:

Francia CJ: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, validation, visualisation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Johnston LM: Supervision, conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Justo RN: Supervision, conceptualization, resources, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Stacey I: Formal analysis, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Fraser JF: Supervision, conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Katzenellenbogen JM: Supervision, conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, validation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

- 1. Katzenellenbogen JM, Bond‐Smith D, Seth RJ, et al. Contemporary incidence and prevalence of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia using linked data: the case for policy change. J Am Heart Assoc 2020; 9: e016851.

- 2. Wyber R, Noonan K, Halkon C, et al. Ending rheumatic heart disease in Australia: the evidence for a new approach. Med J Aust 2020; 213 (Suppl 10): S3. https://www.mja.com.au/system/files/2020‐11/MJA%20213_10_16%20Nov%20Supp_Telethon.pdf

- 3. Casey D, Turner P. Australia’s rheumatic fever strategy three years on. Med J Aust 2024; 220: 170‐171. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2024/220/4/australias‐rheumatic‐fever‐strategy‐three‐years

- 4. Stacey I, Katzenellenbogen J, Hung J, et al. Pattern of hospital admissions and costs associated with acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia, 2012–2017. Aust Health Rev 2024; 49: AH24148.

- 5. Tarrago A, Veit‐Prince E, Brolan CE. “Simply put: systems failed”: lessons from the Coroner’s inquest into the rheumatic heart disease Doomadgee cluster. Med J Aust. 2024; 221: 13‐16. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2024/221/1/simply‐put‐systems‐failed‐lessons‐coroners‐inquest‐rheumatic‐heart‐disease

- 6. Queensland Health. Ending Rheumatic Heart Disease: Queensland First Nations Strategy 2021–2024 final report. Brisbane: Queensland Health, 2024. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0032/1364936/Final‐report_EndingRHD_QLD‐FN‐Strategy2021‐2024.pdf (viewed Nov 2024).

- 7. Hospital and Health Boards (Health Equity Strategies) Amendment Regulation 2021 (Qld). https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/asmade/sl‐2021‐0034 (viewed Oct 2024).

- 8. Woods JA, Sodhi‐Berry N, MacDonald BR, et al. Are we missing opportunities to detect acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in hospital care? A multijurisdictional cohort study. Aust Health Rev 2024; 49: AH23273

- 9. Huria T, Palmer SC, Pitama S, et al. Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples: the CONSIDER statement. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019; 19: 173.

- 10. Katzenellenbogen JM, Bond‐Smith D, Seth RJ, et al. The End Rheumatic Heart Disease in Australia Study of Epidemiology (ERASE) Project: data sources, case ascertainment and cohort profile. Clin Epidemiol 2019; 11: 997‐1010.

- 11. Bond‐Smith D, Seth R, de Klerk N, et al. Development and evaluation of a prediction model for ascertaining rheumatic heart disease status in administrative data. Clin Epidemiol 2020; 12: 717‐730.

- 12. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Indigenous identification in hospital separations data: quality report (AIHW Cat. No. IHW 90). Canberra: AIHW, 2013. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/adcaf32e‐d2d1‐4df0‐b306‐c8db7c63022e/13630.pdf (viewed Nov 2024).

- 13. World Bank. World bank country and lending groups. Washington: World Bank Group. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519‐world‐bank‐country‐and‐lending‐groups (viewed Dec 2024).

- 14. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rural, regional and remote health: a guide to remoteness classifications (AIHW Cat. No. PHE 53; Rural Health Series No. 4). Canberra: AIHW, 2004. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/9c84bb1c‐3ccb‐4144‐a6dd‐13d00ad0fa2b/rrrh‐gtrc.pdf?v=20230605184523&inline=true (viewed Nov 2024).

- 15. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Information paper: Census of Population and Housing — Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas, Australia, 2001. Canberra: ABS, 2003. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/allprimarymainfeatures/09D68973F50B8258CA2573F0000DA181 (viewed Aug 2024).

- 16. Ahmad OB, Boschi‐Pinto C, Lopez AD, et al. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard (GPE Discussion Paper Series No. 31). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default‐source/gho‐documents/global‐health‐estimates/gpe_discussion_paper_series_paper31_2001_age_standardization_rates.pdf (viewed Oct 2024).

- 17. Bennett J, Zhang J, Leung W, et al. Rising ethnic inequalities in acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease, New Zealand, 2000–2018. Emerg Infect Dis 2021; 27: 36‐46.

- 18. Kang K, Chau KWT, Howell E, et al. The temporospatial epidemiology of rheumatic heart disease in Far North Queensland, tropical Australia 1997–2017; impact of socioeconomic status on disease burden, severity and access to care. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2021; 15: e0008990.

- 19. Agenson T, Katzenellenbogen JM, Seth R, et al. Case ascertainment on Australian registers for acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 5505.

- 20. Rouhiainen O, Gatti J, Ramadani S, et al. Missed opportunities for preventing or diagnosing acute rheumatic fever: a retrospective cohort study of 20 young Australians diagnosed with rheumatic heart disease on screening echocardiography. J Paediatr Child Health 2025; 61: 741‐746.

- 21. Thandrayen J, Stacey I, Oliver J, et al. Estimating the true number of people with acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease from two data sources using capture–recapture methodology. Aust Health Rev 2024; 49: AH24267.

- 22. Stacey I, Knight Y, Ong CMX, et al. Notification of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in hospitalised people in the Midwest region of Western Australia, 2012–2022: retrospective administrative data analysis. Med J Aust 2024; 221: 493‐494. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2024/221/9/notification‐acute‐rheumatic‐fever‐and‐rheumatic‐heart‐disease‐hospitalised

- 23. Lansbury N, Memmott PC, Wyber R, et al. Housing initiatives to address Strep A infections and reduce RHD risks in remote Indigenous communities in Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2024; 21: 1262.

- 24. Meier‐Stephenson V, Hawkes MT, Burton C, et al. A phase 1 randomized controlled trial of a peptide‐based group A streptococcal vaccine in healthy volunteers. Trials 2024; 25: 781.

- 25. Cooper J, Enkel SL, Moodley D, et al. “Hurts less, lasts longer”; a qualitative study on experiences of young people receiving high‐dose subcutaneous injections of benzathine penicillin G to prevent rheumatic heart disease in New Zealand. PLoS One 2024; 19: e0302493.

Abstract

Objectives: To determine the incidence and prevalence of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD) in Queensland during the period 2017–2021.

Study design: Population‐level retrospective cohort study using linked administrative data.

Setting, participants: Queensland residents aged younger than 45 years for ARF and younger than 55 years for RHD, identified from hospital, emergency department, death and Queensland RHD Register records for the period 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2021.

Main outcome measures: Age‐specific and age‐standardised incidence and prevalence of ARF and RHD; and age‐standardised incidence and prevalence ratios comparing Indigenous and non‐Indigenous populations.

Results: 736 ARF episodes occurred among 670 people (395 [54%] female participants; 609 [83%] Indigenous). Of 4519 prevalent RHD cases aged < 55 years who were alive on 1 July 2021, 2655 (59%) were female, 2169 (48%) were Indigenous, and 1846 (41%) had severe disease. Previous ARF was recorded for 362 cases (8%). Among RHD cases aged younger than 25 years, 633 of 790 Indigenous individuals (80%) and 133 of 408 non‐Indigenous individuals (33%) had RHD Register records. Indigenous age‐standardised incidence (< 45 years) was 60.2 times higher (95% CI, 55.6–64.2) than non‐Indigenous incidence for first ever ARF, 68.6 times higher (95% CI, 62.3–72.5) for total ARF, and 18.9 times higher (95% CI, 13.5–24.1) for RHD. For Indigenous people aged < 55 years, prevalence was 22.6 times higher (95% CI, 16.2–27.3) for ARF/RHD, 18.4 times higher (95% CI, 12.9–24.1) for RHD, and 12.1 times higher (95% CI, 8.3–15.9) for severe RHD. The overall burden of ARF and RHD was highest in northern Queensland health districts, whereas cases in the non‐Indigenous population were concentrated in metropolitan south‐east Queensland.

Conclusions: The vast disparity in ARF and RHD burden between Indigenous and non‐Indigenous Queenslanders indicates an urgent need for targeted, community‐led prevention strategies. Under‐representation of non‐Indigenous youth in the RHD Register suggests improved clinical awareness and reporting is needed. Further investigation is warranted to inform equitable responses.