Outcomes for people with chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) have improved markedly since the introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in the early 21st century, together with molecular monitoring and better supportive care.1 Changes in survival can be a good indicator of advances in clinical and supportive care, and differences in survival gains can indicate disparities in access to improved care because of remoteness, cultural or language barriers, or socio‐economic circumstances.2

We therefore examined survival for people diagnosed with CML in South Australia during 1980–2020, overall and by age group and other socio‐demographic characteristics by analysing South Australian Cancer Registry data. We included data for all people diagnosed with CML (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology [ICD‐O‐3] morphology codes 9863/3, 9875/3, and 9876/33) during 1 January 1980 – 31 December 2020. We extracted the date of diagnosis, age, sex, country of birth, and residential code‐based remoteness (Australian Statistical Geography Standard)4 and socio‐economic status (Index of Relative Socioeconomic Advantage and Disadvantage, IRSAD),5 as well as the date and cause of death (CML‐related or other). Cause of death information in the South Australian Cancer Registry is based on death certificate notifications, case note reviews, and linkage with the National Death Index.

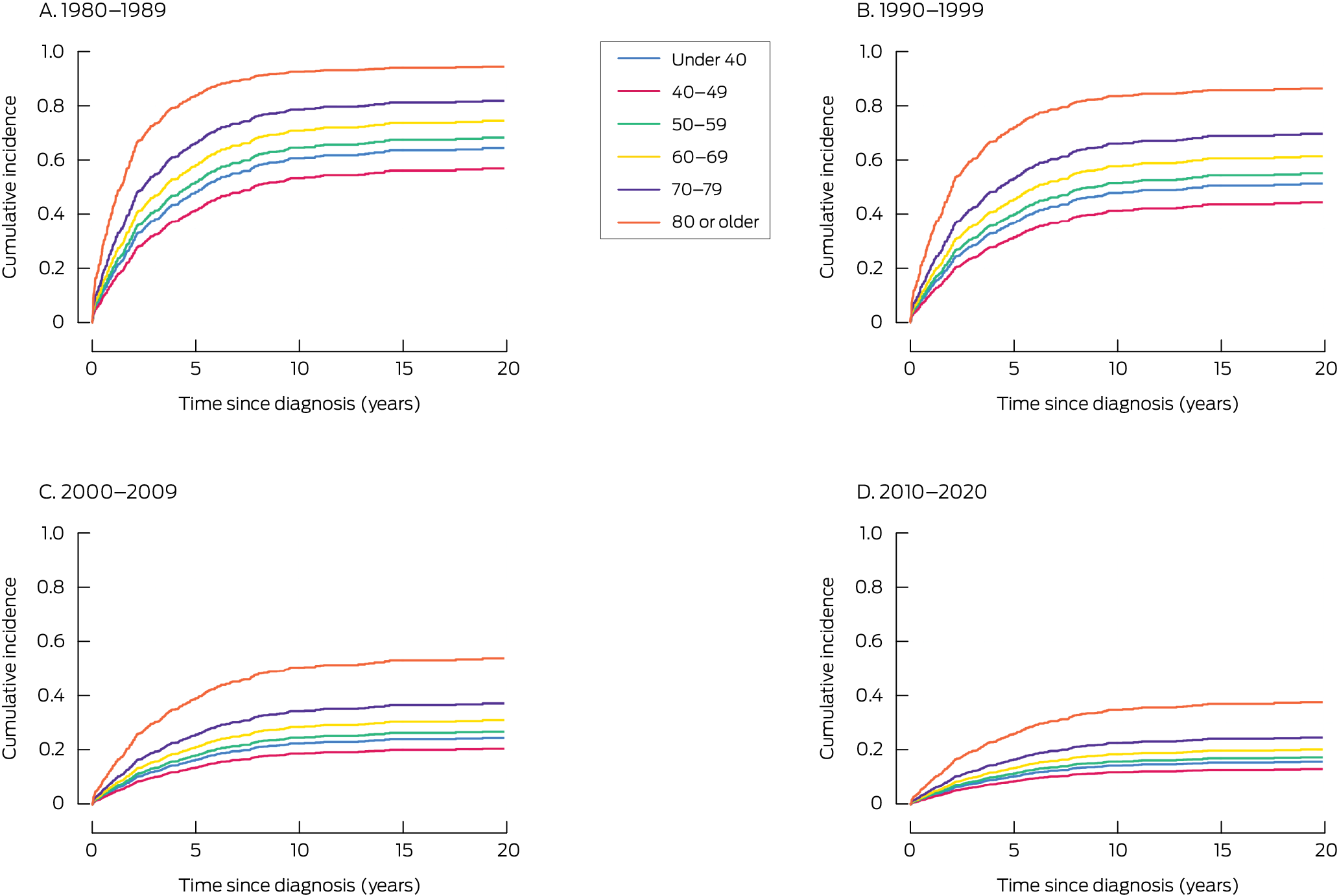

Disease‐specific survival was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of CML‐related death, censored at 31 December 2020. We assessed the influence of socio‐demographic characteristics on disease‐specific mortality using multivariate competing risk regression (Stata stcrreg command); death from other causes was a competing risk,6 and the analysis was adjusted for age, sex, diagnosis period, country of birth, remoteness, and socio‐economic status. Differences in change in disease‐specific mortality by age group were assessed using multivariate competing risk regression models that included an interaction term for diagnosis period and age group (10‐year categories). We report subdistribution hazard ratios (sHR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI); we also provide cumulative incidence function curves by age group and decade of diagnosis. Statistical analyses were conducted in Stata 17. We report our study according to the STROBE guidelines for cohort studies.7 It was approved by the SA Health Human Research Ethics Committee, which waived the requirement for individual consent to data access (HREC/SAH2022 HRE0020).

During 1980–2020, 930 people (median age, 62 years; interquartile range [IQR], 47–75 years) were diagnosed with CML in South Australia, of whom 399 (43%) had died of CML (median follow‐up, 3.8 years; IQR, 1.4–9.4 years) (Supporting Information, table 1). Disease‐specific mortality risk increased with age, and was greatest for people aged 80 years or older at diagnosis (v under 40 years: adjusted sHR, 2.76; 95% CI, 1.90–4.01) and was lower during 2010–2020 than 1980–1989 (adjusted sHR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.12–0.24) (Box 1). Disease‐specific mortality had declined significantly in all age groups, but improvement was less marked for people aged 70–79 or 80 years or older (Box 2).

Disease‐specific mortality for people in South Australia with CML declined substantially during 1980–2020, particularly during the early 2000s, when tyrosine kinase inhibitors were introduced. These improvements were noted for all age groups, but were less marked for people aged 80 years or older at diagnosis. Improvement during 1990–1999 was probably linked with the introduction of clinical protocols, better supportive care, allogeneic transplantation, and early access to imatinib trials.8 The smaller improvements for people aged 80 years or older we report may partly reflect reliance on death certification for ascertaining CML‐related deaths and changes in registration practices.

Survival for people with CML has long been poor. Both earlier treatments, such as arsenic, radiation therapy, and hydroxyurea, and more recent approaches, such as chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation (until 2003), had only limited success. The Philadelphia chromosome (abnormal chromosome 22), present in the bone marrow of most people with CML, was first described in 1960, and its BCR‐ABL fusion gene was identified and sequenced in the 1980s. The use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors for targeted therapy soon followed;9 imatinib was the prototype of the first generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors that became available from 2000, and had an immediate impact on five‐year survival for people with CML.10 Second and third generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as dasatinib, nilotinib, and asciminib, provide more targeted therapy and have fewer side effects, and therapeutic compliance is better. However, the marked improvement in survival associated with imatinib is not as evident for second and third generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors.11,12 All people in Australia with CML, including those over 80 years of age, have access to second and third generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

In 1995, a Centre of Excellence that integrated service teaching and research was established in South Australia for managing people with CML.13 Tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy can now be discontinued for many people with CML who are monitored for minimal residual disease, as determined by BCR‐ABL quantification.

Disease‐specific mortality for people with CML has declined substantially with the introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and death from CML is now infrequent.

Box 1 – Risk of death from chronic myeloid leukaemia and socio‐demographic characteristics of 930 people diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukaemia, South Australia, 1980–2020: multivariate competing risk regression analysis*

|

Characteristic |

Adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio (95% CI) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Men |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Women |

0.93 (0.75–1.15) |

||||||||||||||

|

Age group (years) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Under 40 |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

40–49 |

0.82 (0.54–1.24) |

||||||||||||||

|

50–59 |

1.11 (0.80–1.54) |

||||||||||||||

|

60–69 |

1.32 (0.95–1.84) |

||||||||||||||

|

70–79 |

1.65 (1.18–2.32) |

||||||||||||||

|

80 or older |

2.76 (1.94–4.01) |

||||||||||||||

|

Country of birth† |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Australia |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Other (English‐speaking) |

1.17 (0.83–1.65) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other (not English‐speaking |

1.27 (0.96–1.68) |

||||||||||||||

|

Area of residence (ARIA+)3 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Major city |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Regional (inner and outer) |

0.90 (0.64–1.28) |

||||||||||||||

|

Remote/very remote |

1.12 (0.85–1.48) |

||||||||||||||

|

Socio‐economic status (IRSAD quintiles)5 |

|

||||||||||||||

|

1 (least advantaged)5 |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

2 |

1.00 (0.72–1.37) |

||||||||||||||

|

3 |

1.07 (0.78–1.48) |

||||||||||||||

|

4 |

0.99 (0.72–1.37) |

||||||||||||||

|

5 (most advantaged) |

0.96 (0.69–1.33) |

||||||||||||||

|

Diagnosis period |

|

||||||||||||||

|

1980–1989 |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

1990–1999 |

0.70 (0.54–0.91) |

||||||||||||||

|

2000–2009 |

0.27 (0.20–0.37) |

||||||||||||||

|

2010–2020 |

0.17 (0.12–0.24) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

ARIA+ = Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia; CI = confidence interval; IRSAD = Index of Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage. * Death from other causes as the competing risk; adjusted for sex, age, country of birth, area of residence, socio‐economic status, and diagnostic period. † Missing data: 53 people excluded from analysis. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Chronic myeloid leukaemia‐specific mortality after diagnosis, South Australia, 1980–2020, by decade of diagnosis and age group (years): cumulative incidence function plots (modelled)*

* The multivariate competing risk regression analysis of incidence by age and decade of diagnosis is reported in the Supporting Information, table 2.

Received 26 September 2024, accepted 13 August 2025

- 1. Ross DM, Hughes TP. Cancer treatment with kinase inhibitors: what have we learnt from imatinib? Br J Cancer 2004;90:12‐19.

- 2. Dickman PW, Adams HO. Interpreting trends in cancer patient survival. Intern Med 2006; 260: 103‐117.

- 3. World Health Organization. International classification of diseases for oncology, 3rd edition (ICD‐O‐3). 2000. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42344 (viewed Sept 2025).

- 4. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): volume 5. Remoteness structure (1270.0.55.005). 31 Mar 2013. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/1270.0.55.005July%202011?OpenDocument (viewed Mar 2024).

- 5. Australian Bureau of Statistics. IRSAD. In: Census of Population and Housing: Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016 (2033.0.55.001). https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2033.0.55.001~2016~Main%20Features~IRSAD~20 (viewed Sept 2025).

- 6. Fine JP, Gray RG. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999; 94: 496‐509.

- 7. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008; 61: 344‐349.

- 8. Hughes TP, Goldman JM. Chronic myeloid leukemia. In: Hoffman R, editor. Haematology: Basic principles and practice. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier, 2013; pp. 1142‐1159.

- 9. Goldman JM. Chronic myeloid leukemia: a historical perspective. Semin Hematol 2010; 47: 302‐311.

- 10. Pulte D, Gondos A, Redaniel MT, Brenner H. Survival with chronic myelocytic leukemia: comparisons of estimates from clinical trial settings and population‐based cancer registries. Oncologist 2011; 16: 663‐671.

- 11. Hughes TP, Leber B, Cervantes F, et al. Sustained deep molecular responses in patients switched to nilotinib due to persistent BCR‐ABL1 on imatinib: final ENESTcmr randomised trial results. Leukemia 2017; 31: 2529‐2531.

- 12. Hughes TP, Ross DM. Moving treatment free remission into mainstream clinical practice in CML. Blood 2016; 128: 17‐23.

- 13. Kearney BJ. The Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science. Med J Aust 1997; 167: 614‐617. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/1997/167/11/institute‐medical‐and‐veterinary‐science

Data Sharing:

The de‐identified data we analysed are not publicly available, but requests to the corresponding author for the data will be considered on a case‐by‐case basis.

The study was funded by the Royal Adelaide Hospital Contributing Haematologists Research Project Grant Fund.

No relevant disclosures.

Author contributions:

Brendon Kearney conceived the study, analysed the statistics, and co‐wrote the manuscript. Kerri Beckman analysed the data and co‐wrote the manuscript. Tim Hughes, David Yeung, and Naranie Shanmuganathan participated in discussions from the study conception through various iterations and subsequent reviews of the manuscript.