The known: Concerns have been expressed about delays between the first symptoms of endometriosis and its diagnosis in Australian women. General practitioners are the first point of contact with the health system for most women, but little is known about endometriosis presentation and management in general practice.

The new: The proportion of women diagnosed with endometriosis at Australian general practices almost doubled during 2011–2021. Women presented with a broad range of symptoms. The median time from first symptoms to diagnosis was 2.5 years.

The implications: Supporting general practitioners in the identification and management of endometriosis could reduce diagnostic delays and optimise clinical care.

Endometriosis is a complex chronic health condition, defined by the presence of endometrium‐like tissue outside the uterus.1 In Australia, 14% of women have clinically confirmed or suspected endometriosis by the age of 44–49 years.2 The mean delay between symptom onset and diagnosis is about eight years, comprising three years from symptom onset to first seeking medical care and a further five years until surgical diagnosis.3

Endometriosis can have extensive physical, psychosocial, fertility, sexual, employment, education, and social effects on women.4,5 During 2021–22, there were 40 500 endometriosis‐related hospitalisations in Australia and more than 3600 emergency department presentations.2 The estimated annual total economic burden of endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain in women of reproductive age in Australia is INT$6.5 billion.6 The cause of endometriosis is unclear and there is no cure for the lifelong condition.7

In Australia, general practitioners are the first points of contact with the health care system; they provide initial symptom assessment, ongoing management, and referral as required.8 General practitioners provide care for women with endometriosis throughout their lives,9 but little is known about the presentation of endometriosis in general practice or how general practitioners diagnose and manage the condition. Quantitative research about general practitioner encounters with women with endometriosis is scarce.10,11,12 The Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health13 has not examined endometriosis symptoms seen in general practice or the diagnosis and management of the condition by general practitioners. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare has highlighted the need for “national, comparable and reportable data on primary health care activity and outcomes.”14

We therefore examined the presentation, investigation, and clinical management of women diagnosed with endometriosis who attended Australian general practices during 2011–2021.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study, analysing MedicineInsight data, a large national, longitudinal general practice data collection funded by the Australian Department of Health, Disability and Ageing since 2011.15 We report our study according to the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely‐collected Data (RECORD) statement.16

The MedicineInsight data collection has been described in detail elsewhere.17 In summary, MedicineInsight uses third party tools to extract, de‐identify, and securely transmit patient data from the clinical information systems of participating practices to a secure data repository. The extraction tool regularly collects incremental data, producing a longitudinal dataset in which individual patients can be tracked within each practice over time. The MedicineInsight data collection stores data on the demographic characteristics of patients, practice encounters (excluding progress notes), diagnoses, prescribed medications, and pathology tests requested. MedicineInsight includes data from electronic health records for about 662 general practices (8.2% of all Australian practices) and more than 2700 general practitioners across Australia. Practices were recruited to MedicineInsight using non‐random sampling, but the characteristics of MedicineInsight patients are nationally representative of people who attend general practices in Australia.17

Study population

Our study population comprised women aged 14–49 years who were active patients (attended an Australian general practice three or more times) during 1 January 2011 – 31 December 2021. We analysed data for women who attended general practices where documented endometriosis diagnoses were subsequently entered by general practitioners in an electronic medical record diagnosis field, who were aged 14–49 years at the time of the first recorded endometriosis diagnosis, and for whom the diagnosis was recorded during 1 January 2011 – 31 December 2021. We extracted all available electronic medical record data for encounters for each woman until 30 June 2022; data from before 2011 were available for 7741 women (39.0%).

Symptoms, medical imaging, medications

We searched the medical records for each woman (all general practice encounters before the endometriosis diagnosis, from the age of nine years) for endometriosis symptoms (pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, fatigue, heavy menstrual bleeding, altered bleeding, bowel symptoms, infertility, dyspareunia, dysuria) in “encounter reasons” in encounter datasets, “test requested” and “test reasons” in pathology datasets, and “reason” in the prescription dataset (Supporting Information, table 1).

We identified pelvic medical imaging (ultrasound, computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) requested by the general practitioner during the five years preceding the endometriosis diagnosis and for a maximum of five years after the diagnosis (censored at 30 June 2022) by searching free text terms in imaging requests (Supporting Information, table 2).

Medications prescribed by the general practitioner during the five years preceding the endometriosis diagnosis and for a maximum of five years after the diagnosis (censored at 30 June 2022) were identified using World Health Organization Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes (Supporting Information, table 2).18 The items examined included long acting reversible contraceptives (levonorgestrel intrauterine device [IUD], etonogestrel implant, copper IUD), other hormonal contraceptives (combined oral contraceptive pills, progestogen‐only pills, depot injection, vaginal ring), other hormonal medications (progestogens), medications for pain management (non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, opioids, tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentinoids), and medications for menstrual flow management (tranexamic acid).

Patient characteristics

Included covariates were age at time of first endometriosis diagnosis, concessional health care card status, smoking status, Indigenous status, and residential postcode remoteness and socio‐economic standing. Smoking status was determined at the time of endometriosis diagnosis as never smoked, formerly smoked (smoking cessation prior to endometriosis diagnosis recorded), and never smoked. Women whose Indigenous status was recorded as unknown or missing were categorised as non‐Indigenous.19 Remoteness was defined according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) remoteness areas;20 data for inner and outer regional areas, and for remote and very remote areas, were combined because of the small numbers involved. Socio‐economic standing was defined according to the Index of Relative Socio‐Economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD), categorised as very low (deciles 1 or 2), low (3 or 4), middle (5 or 6), high (7 or 8), or very high (9 or 10).21 We also extracted data related to diagnostic flags for a range of conditions present at the time of the endometriosis diagnosis, including anxiety, asthma, chronic pain, depression, and polycystic ovarian syndrome.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were summarised as means with standard deviations (SDs) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs); categorical data were summarised as counts and proportions.

The annual prevalence of endometriosis (overall and by age group) was computed by dividing the number of women with documented endometriosis diagnoses by the total number of patients who attended MedicineInsight general practices in the corresponding year. Standardised rates are adjusted for the age distribution of the population in the respective calendar year, with direct standardisation against the 2001 Australian standard population.22 We assessed changes in prevalence using Joinpoint Regression Software 4.9.0.1 (National Cancer Institute); we report annual percentage change (APC) with its 95% confidence interval (CI). Time to endometriosis diagnosis was calculated by subtracting the date of first endometriosis diagnosis from the date of the first documented endometriosis symptom; we report median time to diagnosis with its IQR. The statistical significance of differences in the prevalence of medication prescribing and medical imaging requests in the five years preceding and the five years after endometriosis diagnosis were assessed using McNemar tests for matched data, using the Stata mcc command, generating univariate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. For this analysis individual women served as their own controls. We also calculated the annual prescribing of medications by general practitioners during the five years preceding and the five years after endometriosis diagnosis; the denominator was the number of women who attended the general practice in a year. Statistical analyses (other than joinpoint analysis) were performed in Stata MP 18.

Ethics approval

The MedicineInsight Data Governance Committee approved the study (protocol 2019‐003); the University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee exempted our analysis of non‐identifiable data from formal ethics review.

Results

MedicineInsight data were available for 1 724 567 women aged 14–49 years who were active general practice patients during 2011–2021; first endometriosis diagnoses at their regular general practices were recorded for 19 786 women (Supporting Information, figure 1).

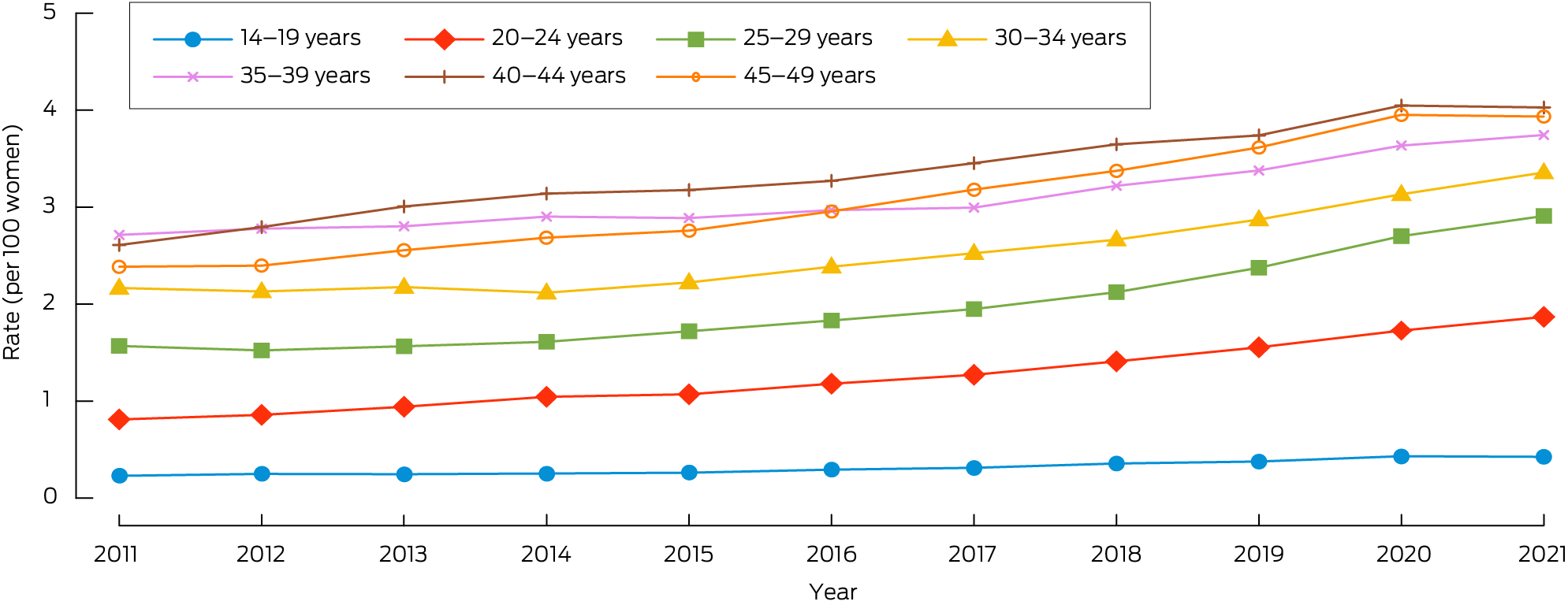

The annual age‐standardised prevalence of documented endometriosis diagnoses among women who attended general practices increased from 1.78 per 100 women in 2011 to 2.11 per 100 women in 2016 (APC, 3.57%; 95% CI, 2.52–4.35%), and to 2.86 per 100 women in 2021 (APC [2016–2021], 6.77%; 95% CI, 6.15–7.67%). The largest relative increase was among women aged 20–24 years, from 0.81 per 100 in 2011 to 1.87 per 100 women in 2021 (230% increase) (Box 1).

The median age at the time of endometriosis diagnosis was 32 years (IQR, 26–39 years); 9611 women (48.6%) had never smoked, 13 061 (66.0%) lived in major cities, and 5194 (26.4%) lived in areas of very high socio‐economic standing. Among the other medical conditions recorded were depression (4745 women, 24.0%), anxiety (4456, 22.5%), and asthma (2770, 14.0%) (Box 2). The median number of primary care visits during the five years preceding the endometriosis diagnosis was 15 (IQR, 5–32 visits).

At least one symptom was documented for 13 202 women (66.7%) prior to endometriosis diagnosis. The most frequent symptoms were pelvic pain (8073 women, 40.8%), dysmenorrhea (4371, 22.1%), fatigue (3815, 19.3%), and heavy menstrual bleeding (2976, 15.0%); 7600 women (57.6%) had two or more symptoms. In women with at least one documented symptom, the median time from symptom documentation to endometriosis diagnosis was 2.5 years (IQR, 0.9–5.6 years), and the mean time 3.8 years (SD, 3.9 years). The median time was shortest for women with infertility (1.4 years; IQR, 0.6–4.1 years) or dyspareunia (1.4 years; IQR, 0.5–3.7); it was longest for women with fatigue (3.0 years; IQR, 1.3–6.0 years) or bowel symptoms (2.9 years; IQR, 1.0–6.1 years) (Box 3).

Pelvic ultrasound was the most frequent medical imaging modality, requested by general practitioners before or after the endometriosis diagnosis for 11 278 women (58.7%). Fewer women were referred for pelvic CT (895, 4.5%) or MRI (137, 0.7%) (Box 4). The proportion of women for whom pelvic ultrasound was requested during the five years preceding diagnosis increased from 202 of 1068 of women diagnosed in 2011 (18.9%) to 1099 of 2259 of women diagnosed in 2021 (48.6%) (Supporting Information, figure 2).

The proportions of women who received general practitioner prescriptions were larger during the five years following than the five years preceding endometriosis diagnoses for levonorgestrel IUDs (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.36–1.65) and non‐contraceptive progestogens (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.51–1.81), and smaller for oral contraceptive pills (OR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.45–0.50). The proportions of women prescribed opioids (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.29–1.42), tricyclic antidepressants (OR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.77–2.11), and gabapentinoids (OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 2.30–2.91) were also larger after endometriosis diagnosis (Box 5). The proportion for each medication type was highest one year after the diagnosis of endometriosis, but then declined (Supporting Information, figures 3 to 5). The proportion of women prescribed any hormonal contraception declined from 9335 (47.2%) during the five years preceding endometriosis diagnosis to 7629 (38.6%) during the five years following diagnosis (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.60–0.66).

Discussion

The proportion of women aged 14–49 years who received documented diagnoses of endometriosis at Australian general practices increased considerably during 2011–2021, to almost 3% of active female general practice patients. They presented with a range of menstrual and other symptoms, and the median time from first documented symptoms to first documented endometriosis diagnosis was 2.5 years (IQR, 0.9–5.6 years); the delay for one in four women was five years or longer. General practitioners frequently requested clinical investigations and provided prescriptions for women diagnosed with endometriosis; we found notable changes in pelvic ultrasound requests both by year of diagnosis and before and after endometriosis diagnosis.

The increase in endometriosis prevalence we found could reflect increased awareness of the condition in the community and among health professionals following actions by advocacy groups, as well as improved use and quality of clinical investigations, such as pelvic ultrasound. The marked change in prevalence since 2016 we report preceded publication of the 2018 Australian National Action Plan on Endometriosis.23

The median time from first documented symptoms to endometriosis diagnosis of 2.5 years is within the range reported by other studies (0.9 to eight years).24 The differences in reported diagnosis time may be related to differences in study populations and methodology, and in health care practices. Further, most previous studies were cross‐sectional surveys, which are prone to response and recall biases. The most recent Australian survey evaluating diagnosis time reported a mean delay of 4.9 years,3 similar to the mean diagnosis time in our study (3.8 years), indicating significant delays in obtaining an endometriosis diagnosis. Median time to diagnosis was shorter for women with specific symptoms (eg, infertility, pelvic pain), than for those with non‐specific symptoms (eg, fatigue, dysuria). Factors that contribute to delays in primary care diagnosis of endometriosis in Australia25 and the United Kingdom26 include negative experiences with general practitioners, including feeling dismissed, symptoms not being taken seriously, and general practitioners lacking essential knowledge about endometriosis, delaying referrals to specialists, and providing inconsistent advice. Satisfaction with medical support among women with endometriosis is low.27

We found that women with endometriosis present to general practitioners with a broad range of symptoms, including some that are non‐specific and can be overlooked or mistaken as indicating other conditions. This finding indicates the difficulty for general practitioners of recognising symptoms as possibly being related to endometriosis, which could increase the time to diagnosis. Our finding is consistent with those of other studies in which general practitioners in Australia25,28 and the United Kingdom9 reported diagnostic difficulties because of the non‐specific, multiple, and complex symptoms with which women present. This can lead to general practitioners trying treatments both as therapeutic interventions and to assist with the diagnosis.9 Diagnosis and management problems are further indicated by the frequency of other conditions in women with endometriosis, as also previously reported.13

Although the overall pattern of hormonal treatment in this study was in concordance with Australian clinical guideline recommendations for the management of endometriosis,29 the proportion of women prescribed levonorgestrel IUDs by their general practitioner during the five‐year periods before and after endometriosis diagnosis was only 10.0%; in the United Kingdom, the proportion was about 15% in 2017,12 and the estimated proportion of levonorgestrel IUD users in the general Australian population in 2021 was 10.8%.30 Long acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) can be effective treatments for women with endometriosis but are not used as much in Australia as overseas.31,32 This may be due in part to the low number of general practitioners who provide insertions and the difficulty in identifying general practitioners and practice nurses trained to insert and remove LARC.33 The Australian Contraception and Abortion Primary Care Practitioner Support Network online community of practice was developed to assist primary care practitioner IUD inserters to keep their knowledge current and to receive peer support, and it hosts a registry of practitioners trained in IUD and contraceptive implant insertion and removal services in Australia.34,35 In 2024, the Australian government provided funding for primary care practitioner training in IUD insertion.36

The proportion of women prescribed opioids in our study (49.5%) was much higher than reported by a United Kingdom study (1.3–2.2%);12 it was highest during the year following endometriosis diagnosis. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists advises against prescribing opioids for women with endometriosis, given the risks of adverse effects and dependence and the availability of alternative treatment options.29 The appropriate management of pain in women diagnosed with endometriosis should be investigated, including the frequency of opioid prescribing and the doses of opioids prescribed, as regular opioid use can make managing endometriosis‐related pain more difficult. Similarly, the larger proportions of women prescribed gabapentinoids and tricyclic antidepressants, typically used for managing neuropathic pain, in the year following endometriosis diagnosis requires further investigation, given that using these medications for managing endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain is controversial.37

Limitations

The large general practice dataset analysed in this study is broadly nationally representative and avoids subjective biases that often affect studies based on self‐reported information. However, while we restricted the analysis to women considered active patients (three or more encounters within the same general practice during the study period), patient records are not linked across general practices; information about encounters outside the usual general practice are therefore not captured. Duplication of patient information for women who attended several MedicineInsight sites was possible, but the duplication rate for the dataset is estimated to be as low as 4%.16 Identification of eligible women relied on general practitioners documenting an endometriosis diagnosis in the diagnoses field of medical records; for privacy reasons, we could not review individual medical records to assess the validity of documented diagnoses, or whether diagnoses were clinically suspected or surgically confirmed diagnoses. Information was not available about referrals to specialists for assistance with the diagnosis or management of endometriosis. We focused on medical imaging of the pelvic region, which could be requested for reasons other than suspected endometriosis. The medications we examined could also have been prescribed for indications other than endometriosis.

Conclusion

Despite the increasing proportion of women attending Australian general practice with documented diagnoses of endometriosis, considerable delays between initial symptoms and diagnosis are frequent, one in four women with documented symptoms waiting five years or longer. General practitioners are increasingly requesting clinical investigations and prescribing medications for women with endometriosis, and major shifts in practice over time were evident. General practitioners need support in identifying and managing endometriosis. The development of a plan for the diagnosis and management of endometriosis in primary care recently funded under the National Action Plan for Endometriosis may provide such assistance.38

Box 1 – Proportions of women aged 14–49 years attending MedicineInsight general practices (active patients) who were diagnosed in these practices with endometriosis, 2011–2021, by age group*

* The data underlying this graph are included in the Supporting Information, table 1.

Box 2 – Characteristics of women aged 14–49 years at the time of general practitioner documented diagnosis of endometriosis, MedicineInsight general practices, 2011–2021

|

Characteristics |

Number |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

All women |

19 786 |

||||||||||||||

|

Age group (years) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

14–19 |

1163 (5.9%) |

||||||||||||||

|

20–24 |

2945 (14.9%) |

||||||||||||||

|

25–29 |

3511 (17.7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

30–34 |

3835 (19.4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

35–39 |

3491 (17.6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

40–44 |

2866 (14.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

45–49 |

1975 (10.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Concession card status |

|

||||||||||||||

|

No concession card |

13 364 (67.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Pensioner concession card |

4013 (20.3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

2409 (12.2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Smoking status |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Never smoked |

9611 (48.6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Formerly smoked |

4259 (21.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Currently smokes |

4179 (21.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

1737 (8.8%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Socio‐economic standing (IRSAD decile) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Very low (1 or 2) |

2667 (13.6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Low (3 or 4) |

3351 (17.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Middle (5 or 6) |

3994 (20.3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

High (7 or 8) |

4469 (22.7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Very high (9 or 10) |

5194 (26.4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

111 |

||||||||||||||

|

Indigenous status |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander |

460 (2.3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Non‐Indigenous |

19 326 (97.7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Remoteness |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Major city |

13 061 (66.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Inner/outer regional |

6395 (32.3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Remote/very remote |

218 (1.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Missing data |

112 (0.6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other medical conditions |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Depression |

4745 (24.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Anxiety |

4456 (22.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Asthma |

2770 (14.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Polycystic ovarian syndrome |

1254 (6.3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Chronic pain |

660 (3.3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

IRSAD = Index of Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Symptoms for 19 786 women aged 14–49 years documented before the general practitioner diagnosis of endometriosis, MedicineInsight general practices, 2011–2021

|

Symptoms |

Number |

Time to diagnosis (years),* median (IQR) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Pelvic pain |

8073 (40.8%) |

2.5 (0.9–5.7) |

|||||||||||||

|

Dysmenorrhea |

4371 (22.1%) |

2.0 (0.7–4.8) |

|||||||||||||

|

Fatigue |

3815 (19.3%) |

3.0 (1.3–6.0) |

|||||||||||||

|

Heavy menstrual bleeding |

2976 (15.0%) |

1.8 (0.6–4.2) |

|||||||||||||

|

Altered bleeding† |

2478 (12.5%) |

2.5 (0.9–5.2) |

|||||||||||||

|

Bowel symptoms‡ |

2277 (11.5%) |

2.9 (1.0–6.1) |

|||||||||||||

|

Infertility |

1584 (8.0%) |

1.4 (0.6–4.1) |

|||||||||||||

|

Dyspareunia |

1123 (5.7%) |

1.4 (0.5–3.7) |

|||||||||||||

|

Dysuria |

885 (4.5%) |

2.6 (1.0–5.3) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

IQR = interquartile range. * From date of first documented symptom to date of endometriosis diagnosis. † Includes metrorrhagia (irregular or frequent flow, non‐cyclic), menometrorrhagia (frequent, excessive, irregular flow), intermenstrual bleeding (bleeding between regular menses), and dysfunctional uterine bleeding. ‡ Includes dyschesia, irritable bowel syndrome, altered bowel habit, bloating, and pain on defecation. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Pelvic medical imaging requested by general practitioners for 19 786 women aged 14–49 years during the five years preceding and the five years following endometriosis diagnosis, MedicineInsight general practices, 2011–2021*

|

Imaging modality |

Before diagnosis |

After diagnosis |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

Imaging before or after diagnosis |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Ultrasound |

7337 (37.1%) |

6929 (35.0%) |

0.91 (0.87–0.95) |

11 278 (57.0%) |

|||||||||||

|

One request |

4229 (21.4%) |

4022 (20.3%) |

|

5015 (25.4%) |

|||||||||||

|

Two or more requests |

3108 (15.7%) |

2907 (14.7%) |

|

6263 (31.7%) |

|||||||||||

|

Computed tomography |

403 (2.0%) |

517 (2.6%) |

1.30 (1.14–1.49) |

895 (4.5%) |

|||||||||||

|

One request |

361 (1.8%) |

465 (2.4%) |

|

784 (4.0%) |

|||||||||||

|

Two or more requests |

42 (0.2%) |

52 (0.3%) |

|

111 (0.6%) |

|||||||||||

|

Magnetic resonance imaging |

53 (0.3%) |

88 (0.4%) |

1.71 (1.19–2.49) |

137 (0.7%) |

|||||||||||

|

One request |

50 (0.3%) |

81 (0.4%) |

|

124 (0.6%) |

|||||||||||

|

Two or more requests |

3 (< 0.1%) |

7 (< 0.1%) |

|

13 (0.1%) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval. * Five years of follow‐up data were not available for women diagnosed with endometriosis less than five years before the end of the study period. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Medications prescribed by general practitioners for 19 786 women aged 14–49 years during the five years preceding and the five years following endometriosis diagnosis, MedicineInsight general practices, 2011–2021*

|

Medication/device |

Before diagnosis |

After diagnosis |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

New users after endometriosis diagnosis |

Prescribed before or after diagnosis |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Levonorgestrel intrauterine device |

857 (4.3%) |

1227 (6.2%) |

1.50 (1.36–1.65) |

1114 (5.6%) |

1971 (10.0%) |

||||||||||

|

Etonogestrel implant |

1168 (5.9%) |

594 (3.0%) |

0.45 (0.40–0.50) |

471 (2.4%) |

1639 (8.3%) |

||||||||||

|

Combined oral contraceptives |

8169 (41.3%) |

5670 (28.7%) |

0.47 (0.45–0.50) |

2246 (11.4%) |

10 415 (52.6%) |

||||||||||

|

Progestin‐only pills |

1147 (5.8%) |

1232 (6.2%) |

1.10 (1.00–1.19) |

1060 (5.4%) |

2207 (11.2%) |

||||||||||

|

Depot injection |

828 (4.2%) |

721 (3.6%) |

0.83 (0.73–0.93) |

508 (2.6%) |

1336 (6.8%) |

||||||||||

|

Vaginal ring |

162 (0.8%) |

82 (0.4%) |

0.43 (0.31–0.59) |

61 (0.3%) |

223 (1.1%) |

||||||||||

|

Progestogens |

1001 (5.1%) |

1488 (7.5%) |

1.65 (1.51–1.81) |

1231 (6.2%) |

2232 (11.3%) |

||||||||||

|

Tranexamic acid |

1041 (5.3%) |

1156 (5.8%) |

1.13 (1.03–1.24) |

990 (5.0%) |

2031 (10.3%) |

||||||||||

|

Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs |

5972 (30.2%) |

6083 (30.7%) |

1.03 (0.98–1.08) |

3446 (17.4%) |

9418 (47.6%) |

||||||||||

|

Opioids |

6185 (31.3%) |

7124 (36.0%) |

1.35 (1.29–1.42) |

3612 (18.3%) |

9797 (49.5%) |

||||||||||

|

Gabapentinoids |

613 (3.1%) |

1245 (6.3%) |

2.60 (2.30–2.91) |

1030 (5.2%) |

1643 (8.3%) |

||||||||||

|

Tricyclic antidepressants |

1206 (6.1%) |

1924 (9.7%) |

1.93 (1.77–2.11) |

1487 (7.5%) |

2693 (13.6%) |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval. * Five years of follow‐up data were not available for women diagnosed with endometriosis less than five years before the end of the study period. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 26 December 2024, accepted 3 June 2025

- Danielle Mazza1

- Kailash Thapaliya2,3

- Sharinne B Crawford1

- Alissia Hui1

- Maryam Moradi1

- Luke E Grzeskowiak3,4

- 1 Monash University, Melbourne, VIC

- 2 South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide, SA

- 3 SA Pharmacy, Flinders Medical Centre, Adelaide, SA

- 4 College of Medicine and Public Health, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA

Data Sharing:

The study generated no original data.

The study was part of the Endometriosis Management Plan (Endo‐MP) project (E22‐302373) funded by the Australian Department of Health, Disability and Ageing. Research undertaken by Luke Grzeskowiak is supported by the Channel 7 Children’s Research Foundation (CRF‐210323). We thank NPS MedicineWise for their support with the development of this study and the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, MedicineInsight Program for their ongoing role in maintaining this data resource (protocol 2019‐003).

No relevant disclosures.

Author contributions:

All authors (apart from Kailash Thapaliya) contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study. Data analysis was conducted by Kailash Thapaliya and Luke Grzeskowiak. The manuscript was written by Danielle Mazza, Sharinne Crawford, and Luke Grzeskowiak; all authors reviewed and edited versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

- 1. World Health Organization. Endometriosis. 24 Mar 2023. https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/endometriosis (viewed Dec 2024).

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Endometriosis in Australia 2023 (cat. no. PHE 329). Updated 14 Dec 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic‐disease/endometriosis‐in‐australia/contents/about (viewed Nov 2024).

- 3. Armour M, Sinclair J, Ng CHM, et al. Endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain have similar impact on women, but time to diagnosis is decreasing: an Australian survey. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 16253.

- 4. Moradi M, Parker M, Sneddon A, et al. Impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health 2014; 14: 123.

- 5. Moradi M, Parker M, Sneddon A, et al. The Endometriosis Impact Questionnaire (EIQ): a tool to measure the long‐term impact of endometriosis on different aspects of women’s lives. BMC Womens Health 2019; 19: 64.

- 6. Armour M, Lawson K, Wood A, et al. The cost of illness and economic burden of endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain in Australia: a national online survey. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0223316.

- 7. Saunders PTK, Horne AW. Endometriosis: etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell 2021; 184: 2807‐2824.

- 8. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. General practice, allied health and other primary care services. Updated 19 Mar 2025. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/primary‐health‐care/general‐practice‐allied‐health‐and‐other‐primary‐c (viewed Aug 2025).

- 9. Dixon S, McNiven A, Talbot A, Hinton L. Navigating possible endometriosis in primary care: a qualitative study of GP perspectives. Br J Gen Pract 2021; 71: E668‐E676.

- 10. Pugsley Z, Ballard K. Management of endometriosis in general practice: the pathway to diagnosis. Br J Gen Pract 2007; 57: 470‐476.

- 11. Melgaard A, Vestergaard CH, Kesmodel US, et al. Utilization of healthcare prior to endometriosis diagnosis: a Danish case–control study. Hum Reprod 2023; 38: 1910‐1917.

- 12. Cea Soriano L, López‐Garcia E, Schulze‐Rath R, Garcia Rodríguez LA. Incidence, treatment and recurrence of endometriosis in a UK‐based population analysis using data from the Health Improvement Network and the Hospital Episode Statistics database. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2017; 22: 334‐343.

- 13. Gete DG, Doust J, Mortlock S, et al. Associations between endometriosis and common symptoms: findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023; 229: 536.

- 14. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Data gaps and opportunities, In: Endometriosis in Australia 2023. Updated 14 Dec 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic‐disease/endometriosis‐in‐australia/contents/data‐gaps‐and‐opportunities (viewed Nov 2024).

- 15. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. MedicineInsight. Undated. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our‐work/indicators‐measurement‐and‐reporting/medicineinsight (viewed Feb 2024).

- 16. Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al; RECORD Working Committee. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely‐collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med 2015; 12: e1001885.

- 17. Busingye D, Gianacas C, Pollack A, et al. Data resource profile: MedicineInsight, an Australian national primary health care database. Int J Epidemiol 2019; 48: 1741.

- 18. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DD index 2025. Updated 27 Dec 2024. https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index (viewed Dec 2024).

- 19. Gilbert E, Rumbold A, Campbell S, et al. Management of encounters related to subfertility and infertility among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander females in Australian general practice. BMC Womens Health 2023; 23: 410.

- 20. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Remoteness areas: Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) edition 3, July 2021 – June 2026. 21 Mar 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/australian‐statistical‐geography‐standard‐asgs‐edition‐3/jul2021‐jun2026/remoteness‐structure/remoteness‐areas (viewed Apr 2025).

- 21. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Index of Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD). In: Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2021. 27 Apr 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people‐and‐communities/socio‐economic‐indexes‐areas‐seifa‐australia/latest‐release#index‐of‐relative‐socio‐economic‐advantage‐and‐disadvantage‐irsad‐ (viewed Mar 2024).

- 22. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Which population to use for age standardisation? In: Australian demographic statistics, Mar 2013 (3101.0). 26 Sept 2013. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/3101.0Feature+Article1Mar%202013 (viewed Apr 2025).

- 23. Australian Department of Health. National Action Plan for Endometriosis. July 2018. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national‐action‐plan‐for‐endometriosis?language=en (viewed Apr 2025).

- 24. De Corte P, Klinghardt M, von Stockum S, Heinemann K. Time to diagnose endometriosis: current status, challenges and regional characteristics: a systematic literature review. BJOG 2025; 132: 118‐130.

- 25. Rowe HJ, Hammarberg K, Dwyer S, et al. Improving clinical care for women with endometriosis: qualitative analysis of women’s and health professionals’ views. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2021; 42: 174‐180.

- 26. Davenport S, Smith D, Green DJ. Barriers to a timely diagnosis of endometriosis: a qualitative systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2023; 142: 571‐83.

- 27. Lukas I, Kohl‐Schwartz A, Geraedts K, et al. Satisfaction with medical support in women with endometriosis. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0208023.

- 28. Frayne J, Milroy T, Simonis M, Lam A. Challenges in diagnosing and managing endometriosis in general practice: a Western Australian qualitative study. Aust J Gen Pract 2023; 52: 547‐555.

- 29. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Australian living evidence guideline: endometriosis. 2024. https://ranzcog.edu.au/womens‐health/endometriosis (viewed Apr 2025).

- 30. Grzeskowiak LE, Calabretto H, Amos N, et al. Changes in use of hormonal long‐acting reversible contraceptive methods in Australia between 2006 and 2018: a population‐based study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2021; 61: 128‐134.

- 31. Frost JJ, Darroch JE. Factors associated with contraceptive choice and inconsistent method use, United States, 2004. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2008; 40: 94‐104.

- 32. Moreau C, Bohet A, Trussell J, Bajos N. Estimates of unintended pregnancy rates over the last decade in France as a function of contraceptive behaviors. Contraception 2014; 89: 314‐321.

- 33. Mazza D, Bateson D, Frearson M, et al. Current barriers and potential strategies to increase the use of long‐acting reversible contraception (LARC) to reduce the rate of unintended pregnancies in Australia: an expert roundtable discussion. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2017; 57: 206‐212.

- 34. Mazza D, James S, Black K, et al. Increasing the availability of long‐acting reversible contraception and medical abortion in primary care: the Australian Contraception and Abortion Primary Care Practitioner Support Network (AusCAPPS) cohort study protocol. BMJ Open 2022; 12: e065583.

- 35. Srinivasan S, James SM, Kwek J, et al. What do Australian primary care clinicians need to provide long‐acting reversible contraception and early medical abortion? A content analysis of a virtual community of practice. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2024; 51: 94‐101.

- 36. Australian Department of Health and Aged Care. Budget overview: Budget 2024–25. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024‐05/budget‐2024‐25‐budget‐overview.pdf (viewed Dec 2024).

- 37. Marchand G, Masoud AT, Govindan M, et al. Systematic review and meta‐analysis of the efficacy of gabapentin in chronic female pelvic pain without another diagnosis. AJOG Glob Rep 2022; 2: 100042.

- 38. SPHERE Centre of Research Excellence. The Endometriosis Management Plan project. 2024. https://www.spherecre.org/research/current‐trials/endometriosis‐management‐plan (viewed Dec 2024).

Abstract

Objective: To examine the presentation, investigation, and clinical management of women diagnosed with endometriosis in Australian general practices during 2011–2021.

Study design: Open cohort study; analysis of MedicineInsight data.

Setting, participants: Women aged 14–49 years who were active patients at Australian general practices participating in MedicineInsight and were diagnosed with endometriosis at these practices, 1 January 2011 – 31 December 2021.

Main outcome measures: The number of women with first documented diagnoses of endometriosis in general practices and the annual age‐standardised prevalence; documented symptoms prior to documented endometriosis diagnosis; time from initial symptoms to diagnosis; general practitioner requests for diagnostic investigations and prescribing of medications.

Results: First diagnoses of endometriosis at their regular general practices were recorded for 19 786 women during 2011–2021; the annual age‐standardised prevalence increased from 1.78 per 100 women in 2011 to 2.86 per 100 women in 2021. At least one symptom was documented prior to diagnosis for 13 202 women (66.7%), including 8073 (40.8%) with pelvic pain and 4371 (22.1%) with dysmenorrhea. The median time from first symptom documentation to first documented endometriosis diagnosis was 2.5 years (interquartile range, 0.9–5.6 years). The proportion of women for whom general practitioners requested pelvic ultrasound prior to diagnosis increased from 202 of 1068 of those diagnosed in 2011 (18.9%) to 1099 of 2259 women diagnosed in 2021 (48.6%). The proportions of women who received general practitioner prescriptions were larger during the five years after than the five years preceding endometriosis diagnoses for levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (odds ratio [OR], 1.50; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.36–1.65) and non‐contraceptive progestogens (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.51–1.81), and smaller for oral contraceptive pills (OR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.45–0.50). The proportions of women prescribed opioids (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.29–1.42), tricyclic antidepressants (OR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.77–2.11), and gabapentinoids (OR, 2.60; 95% CI, 2.30–2.91) were also larger after endometriosis diagnoses; the proportion for each medication type was highest one year after diagnosis, but then declined.

Conclusion: Our findings provide unique insights into the presentation and management of endometriosis in Australian general practice and could inform interventions for improving the clinical management of this often debilitating condition.