The known: Information regarding disease severity and reasons for hospital admissions of children with COVID-19 in Australia is very limited.

The new: In 2021, more NSW children with SARS-CoV-2 infections were hospitalised for social or welfare reasons (294, 64%; 2.45 per 100 infections) than for medical treatment (165, 36%; 1.38 per 100 infections). Children under six months of age, aged 12–15 years, or with another medical condition were more likely to be hospitalised than other children.

The implications: As acute COVID-19 is typically mild in children, measures that protect them from SARS-CoV-2 but harm their overall wellbeing may be disproportionate. Community support for children with special care needs could reduce the number of hospitalisations.

Since the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) emerged in Wuhan in December 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) has caused more than 6.3 million deaths.1 In children, SARS‐CoV‐2 infections are typically asymptomatic or associated with mild disease, and hospitalisation is uncommon.2,3 Correspondingly, mortality is lower than in adults; the estimated infection fatality rate for people under 18 years of age in England during 2020–21 was five deaths per 100 000 infections4 (adults: 2300 deaths per 100 000 infections5).

Most reports on COVID‐19 in children describe hospitalised patients infected with the original SARS‐CoV‐2 strain or early variants of concern; information about children with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections managed in the community is limited.6,7 Moreover, hospitalisations data frequently do not include the reason for hospitalisation, which may provide important detail about the spectrum of illness in children. Two single centre studies in the United States found that almost half the children admitted to hospital with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections had been admitted for other reasons,8,9 as were 21% of children in a large multicentre study in the United Kingdom.2

In June 2021, an outbreak of the Delta SARS‐CoV‐2 variant of concern developed from a single case in New South Wales, the most populous Australian state. Until this outbreak, infection rates in Australian children had been very low (estimated 0.23% of people under 19 years of age; 95% credible interval, 0.06–0.57%).10 Public health measures such as school closures were promptly introduced to reduce community transmission and to shield children from infection,11 possibly at the cost of their education, wellbeing, and personal development.12,13

In adults, SARS‐CoV‐2 causes a broad spectrum of respiratory tract symptoms, and disease severity is influenced by age and other medical conditions. The clinical features and risk factors for severe COVID‐19 in children are less well defined.14 We therefore investigated the severity and clinical spectrum of COVID‐19 in children managed with community‐based virtual care or in hospital during the 2021 Delta outbreak in NSW.

Methods

We undertook a prospective cohort study of children (under 16 years of age) with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections who received care from virtual or inpatient medical teams of the Sydney Children’s Hospital Network (SCHN; the Children’s Hospital at Westmead and Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick) during 1 June – 31 October 2021.

The SCHN virtualKIDS COVID‐19 outpatient response team (virtualKIDS‐CORT) service was established in March 2020.15 Based on a hospital‐in‐the‐home platform, the service provides telehealth and outreach in‐home clinical assessments by a medical officer and a nursing team in metropolitan Sydney.

In NSW, positive SARS‐CoV‐2 nucleic acid test (NAT) and serology results for children under 16 years of age are recorded in the Notifiable Conditions Information Management System (NCIMS). During 2021, positive test results triggered a public health response comprising a case interview and contact tracing. Screening of close contacts of children with positive test results identified further cases of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, including asymptomatic children.

During the Delta outbreak, all children in the Western, South Western, and South Eastern local health districts in Greater Sydney (all‐age population: 3 million) with confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infections were referred to the virtualKIDS‐CORT for symptom and welfare monitoring. Clinical and social data were collected in regular telehealth reviews (twice daily to twice weekly, according to clinical and social triage risk) or in personal home medical reviews, as required.

Clinical data for children admitted to hospital were obtained by Paediatric Active Enhanced Disease Surveillance (PAEDS) teams. PAEDS is a national collaboration between tertiary children’s hospitals (www.paeds.org.au). Children with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections could be admitted to hospital for medical reasons (for medical care related to COVID‐19 or another condition) or for social reasons; that is, their carer had been hospitalised because of COVID‐19, the child was admitted under public health orders, or the usual care for a child with a chronic health problem was unavailable because of their SARS‐CoV‐2 status (including children under the care of the Department of Communities and Justice, and those requiring mental health support).

PAEDS surveillance nurses actively reviewed clinical and laboratory records of children with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections or paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 (PIMS‐TS; = multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, MIS‐C) and liaised with clinical teams to identify and monitor eligible children who presented to the two SCHN hospitals. This approach comprehensively acquired individual case data that were collated in a national electronic database (REDCap), hosted at the University of Sydney.

Statistical analysis

We report age‐specific SARS‐CoV‐2 infection counts and frequencies (NCIMS data, by epidemiologic week, 1 June – 31 October 2021), both overall and separately for SCHN virtual and hospital care patients, as well as medical and social reason admission rates (denominator: children receiving SCHN virtual care, as all children in the three local health districts were managed by virtualKIDS‐CORT) and intensive care admission and PIMS‐TS rates (denominator: NCIMS infection notifications, as any NSW child requiring intensive care was transferred to an SCHN hospital) (Supporting Information, supplementary methods).

The large number of children managed by the virtualKIDS‐CORT rendered it impractical to characterise the demographic and clinical features of all children managed under this model of care, for which reason we assessed a simple random sample for further analyses (using a web‐based algorithm; stratified by calendar month and sampled to achieve 2:1 ratio of virtualKIDS‐CORT to admitted care [medical reason] cases). Demographic and clinical data for the virtualKIDS‐CORT sample were analysed alongside inpatient data from the two SCHN hospitals, obtained by the PAEDS network. We assessed associations between demographic and clinical characteristics and the clinical features and treatment of COVID‐19, as descriptive statistics and in univariate and multivariable logistic regression models that included age group, sex, Indigenous status, whether the child was a household contact of another infected person, premature birth (at or before 36 weeks’ gestation), fever, cough, rhinorrhoea, and fatigue or malaise. Asthma or viral induced wheeze, other respiratory disease, and cardiac disease were included as factors in univariate analyses, but small sample sizes precluded their inclusion in multivariable models.

Ethics approval

The SCHN human research ethics committee approved PAEDS surveillance, and waived the requirement for individual consent for case data collection (study number 2019/ETH06144). The aggregate reporting of SCHN virtual care data and NCIMS data was approved by the NSW Ministry of Health and the SCHN executive.

Results

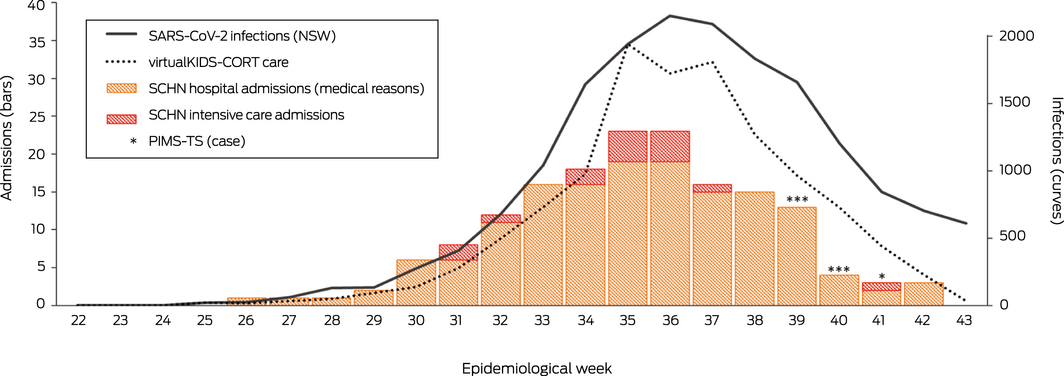

During 1 June – 31 October 2021, confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infections were recorded for 17 474 NSW children under 16 years of age, of whom 11 985 (68.6%) received virtual care coordinated by the SCHN (Box 1). A total of 459 children were admitted to the two SCHN hospitals, 165 under 16 years of age for medical reasons and 294 under 18 years for social reasons. The age distributions of NSW children with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections and of those who received virtual care were similar, but the proportion of medical admissions was highest for children under two years of age (2.9% of infections; 33% of admissions), and nine of the fifteen children admitted to intensive care were aged 12–15 years (Box 2).

The overall medical admission rate for children under 16 years of age was 1.38 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.17–1.59 admissions) per 100 SARS‐CoV‐2 infections; the rate for admissions without an intensive care component was 1.26 (95% CI, 1.06–1.46) per 100 infections, the rate for admissions with an intensive care component 0.09 per 100 infections in NSW (Box 2). The median length of stay for children with medical admissions without an intensive care component was two days (interquartile range [IQR], 1–8 days), and seven days (IQR, 4–11) for those admitted to intensive care during their admission. One death was associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, that of a child who died of pneumococcal meningitis (Box 3).

The 294 children admitted to hospital for social reasons (2.45 [95% CI, 2.18–2.73] per 100 infections) included 202 (69%) who required supervision because their parents or caregivers were hospitalised with COVID‐19, and thirty (10%) for whom usual out‐of‐home‐care services were not available because of their SARS‐CoV‐2‐positive status. The median length of stay for children admitted for social reasons was five days (IQR, 3–10 days) (Box 4).

Children with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections: symptoms

Data for all 165 children admitted to hospital for medical reasons and for a random sample of 344 children cared for by the virtualKIDS‐CORT (2.9% of all children who received virtual care) were included in our further analyses. SARS‐CoV‐2 infections were asymptomatic in 111 of 509 cases (22%). In children with symptomatic disease, rhinorrhoea was the most frequently reported symptom among those receiving virtual care (117 of 232, 50%); in children admitted to hospital, cough (108 of 149, 72%) and fever (99 of 144, 69%) were the most frequent symptoms among those not admitted to intensive care, as also among those admitted to intensive care (cough, fever: each 12 of 15, 80%) (Box 3).

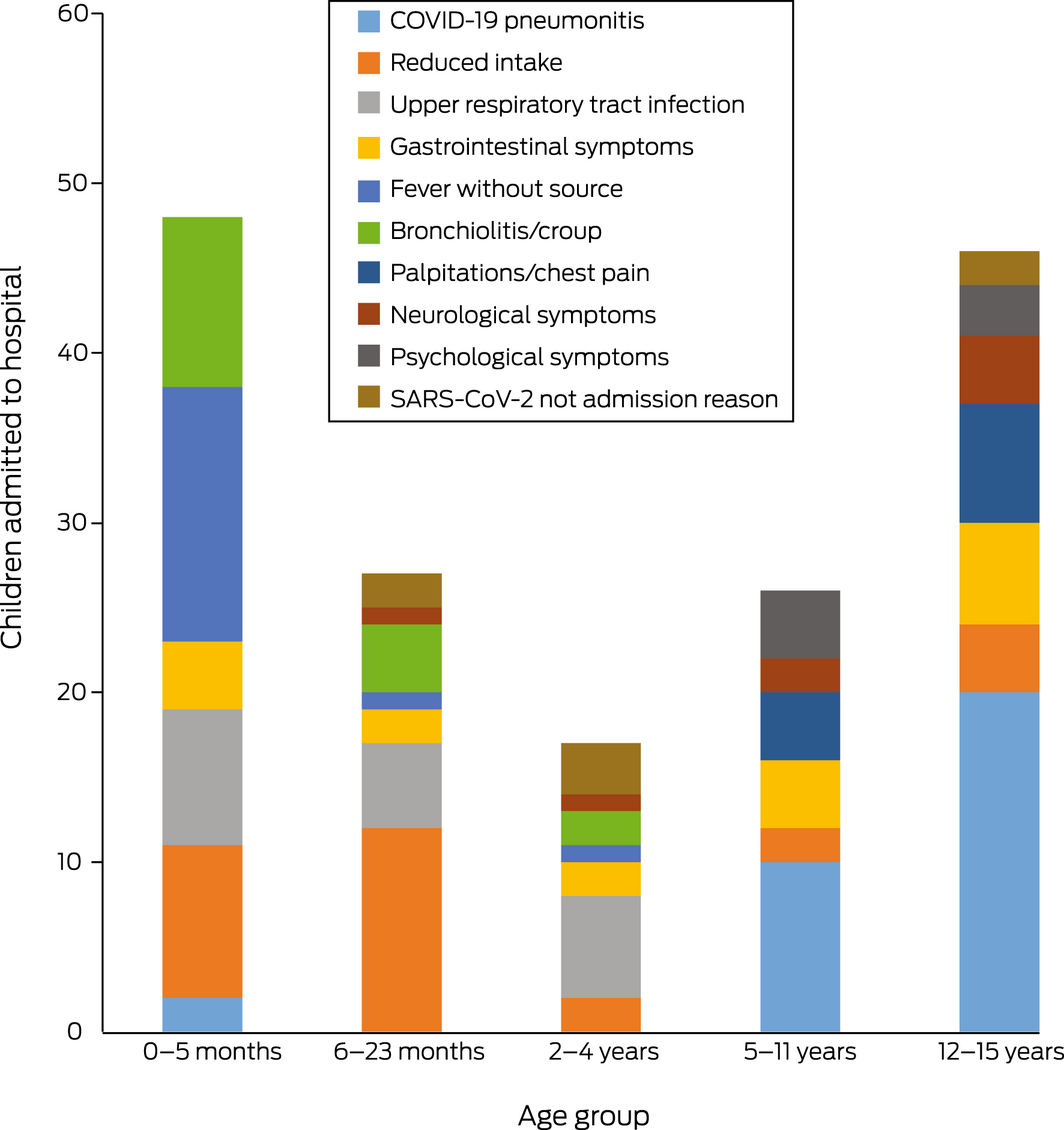

Among the children admitted to hospital for medical reasons, symptoms consistent with common viral infections were frequent in children under two years of age, particularly reduced oral intake (21 of 75, 28%), upper respiratory tract symptoms (13, 17%), and gastrointestinal symptoms (six, 8%); in infants under six months of age, fever without source was also common (15 of 48, 31%). The frequency of lower respiratory tract symptoms suggesting COVID‐19 pneumonitis increased with age (two of 92 children under 5 years, 3%; ten of 26 children aged 5–11 years, 38%; 20 of 46 children aged 12 years or more, 43%). Seven of 150 SARS‐CoV‐2‐positive children admitted to hospital for medical reasons (5%) had been admitted with other primary diagnoses (Box 5).

Children with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections: demographic characteristics

The median age of the children who received care from the virtualKIDS‐CORT was 7.8 years (IQR, 3.8–11.4 years), for those admitted to hospital for medical reasons 2.0 years (IQR, 0.3–11.2 years), and for those admitted to intensive care 12.8 years (IQR, 10.4–15.5 years). Eight of 14 children admitted to intensive care (57%) were overweight (above the 95th centile weight‐for‐age), as were 27 of 139 children admitted to hospital for medical reasons but without an intensive care component (19%). Premature birth (at or before 36 weeks’ gestation) was recorded for 17 of 123 children admitted for medical reasons (14%) and two of 13 admitted to intensive care (15%). The proportion of children admitted to hospital for medical reasons who had asthma was lower than for those who received virtual care (25% v 56%), but the proportions were higher for viral induced wheeze (12% v 0) and other chronic respiratory conditions (13% v 2%) (Box 6).

Uni‐ and multivariable analyses

In our multivariable model, having another medical condition (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 7.42; 95% CI, 3.08–19.3), fever (aOR, 19.0; 95% CI, 8.41–47.6), or cough (aOR, 2.82; 95% CI, 1.18–7.03) were each associated with increased risk of medical admission. In univariate analyses, non‐asthmatic chronic respiratory disease was associated with increased likelihood of medical admission (OR, 9.21; 95% CI, 1.61–174), and asthma/viral induced wheeze was associated with lower likelihood (OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.18–0.78). Likelihood declined with age to 5–11 years, then rose again for those aged 12–15 years. Sex, Indigenous status, and being a household contact of someone with COVID‐19 did not influence the likelihood of medical admission (Box 7).

PIMS‐TS

Seven cases of PIMS‐TS were recorded (0.04% of notified SARS‐CoV‐2 infections in NSW = one case per 2496 infections), each three to six weeks after confirmed or presumed SARS‐CoV‐2 infections. The median age of the children was 3.2 years (IQR, 1.8–7.5 years); four were girls, and one child had another medical condition. Two children were admitted to intensive care; no child with PIM‐TS died.

Discussion

We report the first comprehensive analysis of the severity and disease spectrum of SARS‐CoV‐2 (Delta variant) infections in children in Australia. We provide estimates of hospital and intensive care admission rates, and identified factors associated with hospital admission. We found that the burden of social hospital admissions of children with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection was high in NSW, indicating that crude hospitalisations data may overestimate the burden of severe COVID‐19 in children.

Our findings are consistent with overseas evidence that a large proportion of SARS‐CoV‐2 infections in children are asymptomatic, and that clinical illness in those who develop symptoms is typically mild.2,15 This reassuring finding suggests that we need to carefully consider both the harms of infection and those caused by population‐level shielding of children from infection, which could be considered as disproportionate with respect to disease risk, although the long term effects of infection are still poorly characterised.16 Why COVID‐19 is less severe in children than adults is unclear, but a number of explanations have been proposed, including altered expression and affinity of SARS‐CoV‐2‐binding receptors, and more effective innate immunity in the upper airways.17

We found that medical hospitalisation was more common for children who had other medical conditions, consistent with other reports.2,3,18 Immunodeficiency was recorded for few children admitted to hospital; eight of 14 children admitted to intensive care had overweight, an important risk factor for severe COVID‐19 in adults and children,19 but this factor was not included in our multivariable model because individual weight data were not available for children receiving virtual care. Non‐asthmatic respiratory disease was associated with greater likelihood of hospitalisation, but not asthma/viral induced wheeze, as also found by other investigators.4,15,20 In asthma, the predominant type 2 inflammation leads to IL‐4, IL‐5, and IL‐13 release; IL‐13 downregulates expression of host cell SARS‐CoV‐2 receptors.21

In our study, the proportions of children with SAR‐CoV‐2 infections admitted to hospital for medical reasons were largest for infants (under six months old) and older children (12–15 years). The admission rate for infants probably reflects a cautious management approach. Infants with viral illnesses (eg, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza or enterovirus infections) are often admitted to hospital for observation or supportive care only, so the high medical hospitalisation rate may not reflect an unusual medical risk linked to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.22 It was recently reported that vaccination of pregnant women was effective in averting COVID‐19 requiring hospitalisation in their infants (under six months).23 The proportion of children with adult‐like COVID‐19 pneumonitis increased with age, to 43% among children aged 12–15 years; nine of fifteen children admitted to intensive care were also from this age group. Most NSW teenagers aged 12–15 years are now protected by double‐dose vaccination (79% at 22 June 2022).24

Seven children were admitted to hospital with PIMS‐TS, at a similarly low rate to that associated with the initial SAR‐CoV‐2 strain in Australia.25,26 All children with PIMS‐TS responded well to medical treatment, and only two needed intensive care.

Our findings indicate that children also require social support during a pandemic. Two‐thirds of hospital admissions were for social rather than medical reasons, predominantly because their parents or carers had themselves been hospitalised. The psychological effects of these episodes on children require investigation. A substantial number of children were admitted to hospital because their usual social support services were not available, including those in out‐of‐home care or supported by disability support agencies. Pandemic response plans should be expanded to ensure adequate resources for those who care for children with special care needs.

Our unique virtualKIDS‐CORT model of care is resource‐intensive, but probably reduced the burden on emergency departments by providing parents with reassurance and telehealth support, together with in‐home clinical reviews when clinically indicated. Repeated presentations to hospital by concerned parents of children with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections are common, and providing remote care could reduce the strain on health services and the exposure risk for other patients and health care workers.25,27 However, this model may be unsustainable in the long term, and integrated primary care models have been established to minimise ongoing hospital resource re‐allocation.

Limitations

For practical reasons, we characterised the demographic and clinical features of a random sample of children managed by the virtualKIDS‐CORT rather than the entire group. Further, the small numbers of children with other medical conditions or immunodeficiency mean that our conclusions about their influence on the impact of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

We have established a baseline of clinical spectrum and severity against which future waves of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in Australia can be compared. We found that SARS‐CoV‐2 infections in children were usually asymptomatic or caused only mild disease. Our findings provide clinical information that could inform further research and policy decisions, including considerations about the benefits and harms of population‐level interventions for shielding children from SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, and indicate the importance of ensuring that children with special care needs can be adequately supported in the community during a pandemic.4,21

Open access

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley – The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Box 1 – Epidemiologic curve of confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infections in children under 16 years of age, New South Wales, 1 June – 31 October 2021*

CORT = COVID‐19 outpatient response team; COVID‐19 = coronavirus disease 2019; PIMS‐TS = paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection; SARS‐CoV‐2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SCHN = Sydney Children’s Hospital Network.* By earliest confirmed infection date. VirtualKIDS‐CORT: by admission date; children admitted to SCHN hospitals: by laboratory confirmation of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection; children with PIMS‐TS: by date of illness onset.

Box 2 – Children under 16 years of age with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections in New South Wales, and those who were managed by Sydney Children’s Hospital Network (SCHN) hospitals, 1 June – 31 October 2021, by age group

|

|

|

|

Medical admissions to SCHN hospitals |

|

|||||||||||

|

Age group |

New South Wales |

VirtualKIDS‐CORT |

No intensive care component |

With intensive care component |

Admission rate (all) per 100 infections (95% CI)* |

PIMS‐TS |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

All children |

17 474 |

11 985 |

150 |

15 |

1.38 (1.17–1.59) |

7 |

|||||||||

|

Age (years), median (IQR) |

7.9 (4.1–12.0) |

7.9 (3.9–12.1) |

2.0 (0.3–11.2) |

12.8 (10.4–15.5) |

|

3.2 (1.8–7.5) |

|||||||||

|

Under 6 months |

510 (2.9%) |

416 (3.5%) |

49 (33%) |

1 (7%) |

12.0 (8.9–15.1) |

1 (14%) |

|||||||||

|

6–23 months |

1612 (9.2%) |

1154 (9.6%) |

26 (17%) |

1 (7%) |

2.3 (1.5–3.1) |

1 (14%) |

|||||||||

|

2–4 years |

3289 (18.8%) |

2307 (19.2%) |

20 (13%) |

0 |

0.9 (0.5–1.3) |

3 (43%) |

|||||||||

|

5–11 years |

7685 (44.0%) |

5076 (42.4%) |

22 (15%) |

4 (27%) |

0.5 (0.3–0.7) |

2 (29%) |

|||||||||

|

12–15 years |

4378 (25.1%) |

3032 (25.3%) |

33 (22%) |

9 (60%) |

1.4 (1.0–1.8) |

0 |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CORT = COVID‐19 outpatient response team; IQR = interquartile range; PIMS‐TS = paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection; SARS‐CoV‐2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. * Denominator: number of virtualKIDS‐CORT cases (all children in the three local health districts were managed by virtualKIDS‐CORT). |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Clinical features, treatment, and outcomes for children under 16 years of age who were managed by Sydney Children’s Hospital Network (SCHN) hospitals, 1 June – 31 October 2021

|

Characteristic |

VirtualKIDS‐CORT (random sample) |

Medical admission (no intensive care) |

Medical admission (with intensive care) |

P * |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of patients |

344 |

150 |

15 |

|

|||||||||||

|

Patients with symptoms |

233 (68%) |

150 (100%) |

15 (100%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Fever |

30/219 (14%) |

99/144 (69%) |

12 (80%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Cough |

116/232 (50%) |

108/149 (72%) |

12 (80%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Rhinorrhoea |

117/232 (50%) |

90/148 (61%) |

8 (53%) |

0.14 |

|||||||||||

|

Fatigue/malaise |

66/232 (28%) |

56/143 (39%) |

10 (67%) |

0.003 |

|||||||||||

|

Second pathogen detected |

0/343 |

9 (6%) |

2 (13%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Medications provided |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Antibiotics |

1/50 (2%) |

49/116 (42%) |

13 (87%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Antivirals† |

0/50 |

1/116 (1%) |

8 (53%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Antifungals |

0/50 |

1/115 (1%) |

2 (13%) |

0.019 |

|||||||||||

|

Corticosteroids |

0/50 |

18/116 (16%) |

14 (93%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Systemic anticoagulation |

— |

6/115 (5%) |

10 (67%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Respiratory support |

|

|

|

< 0.001‡ |

|||||||||||

|

None |

— |

134/144 (93%) |

1 (7%) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Low flow oxygen |

— |

7/144 (5%) |

2 (13%) |

|

|||||||||||

|

High flow oxygen |

— |

3/144 (2%) |

2 (13%) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Non‐invasive ventilation |

— |

0/144 |

3 (20%) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Invasive ventilation |

— |

0/144 |

7/ (47%) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Hospital length of stay (days), median (IQR) |

— |

2 (1–8) |

7 (4–11) |

0.015 |

|||||||||||

|

Deaths |

0/344 |

0/150 |

1 (7%) |

0.029 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COVID‐19 = coronavirus disease 2019; IQR = interquartile range; virtualKIDS‐CORT = virtualKIDS COVID‐19 outpatient response team. * virtualKIDS‐CORT v medical admission (with or without intensive care component), or medical admission (with intensive care component) v medical admission (without intensive care component) for characteristics not relevant to virtualKIDS‐CORT care; Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test (hospital length of stay) or Fisher exact test (other characteristics). P < 0.016 deemed statistically significant after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Data for a more comprehensive list of symptoms are included in the Supporting Information, table 1 and figure 1; post hoc multiple comparisons are reported in the Supporting Information, table 2. † Six children were prescribed remdesivir, three acyclovir. ‡ Single χ2 test for range of options. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Children under 18 years of age with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections admitted to Sydney Children’s Hospital Network hospitals for social reasons (“home in the hospital” admissions), New South Wales, 1 June – 31 October 2021

|

Characteristic |

Number |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Total number of children |

294 |

||||||||||||||

|

Total number of family units |

162 |

||||||||||||||

|

Admission rate, per 100 SARS‐CoV‐2 infections (95% CI) |

2.44 (2.18–2.73) |

||||||||||||||

|

Age (years), median (IQR) |

8 (4–13) |

||||||||||||||

|

Under 2 |

41 (14%) |

||||||||||||||

|

2–4 |

45 (15%) |

||||||||||||||

|

5–11 |

117 (40%) |

||||||||||||||

|

12–15 |

84 (29%) |

||||||||||||||

|

16 or older |

7 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Hospital length of stay (days), median (IQR) |

5 (3–10) |

||||||||||||||

|

Initial reason for admission |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Impact of COVID‐19 on parent/carer* |

202 (69%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Child admitted under public health order |

5 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

SARS‐CoV‐2‐positive status affected care or safety of child (Department of Communities and Justice/out‐of‐home care support, 30; disability support, 7; mental health/behaviour support, 6) |

43 (14%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other (unaccompanied minor for medical admission, 34; boarder sibling, 10) |

44 (15%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval; COVID‐19 = coronavirus disease 2019; IQR = interquartile range; SARS‐CoV‐2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. * Nobody available to care for the child at home because one or more carers admitted to hospital with acute COVID‐19 (second carer possibly also unwell with COVID‐19). |

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Clinical manifestations in 164 children under 16 years of age with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections admitted to Sydney Children’s Hospital Network (SCHN) hospitals for medical reasons (with or without intensive care component), New South Wales, 1 June – 31 October 2021, by age group*

COVID‐19 = coronavirus disease 2019; SARS‐CoV‐2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.* COVID‐19 pneumonitis includes four cases with fever and breathlessness, but no chest X‐ray was performed; reduced intake includes all cases in which inadequate fluid intake was the primary reason for admission; gastrointestinal symptoms included vomiting, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain without a specific diagnosis; psychological symptoms included acute mental state or behavioural disturbance without identified organic cause; palpitations/chest pain included one case of confirmed pericarditis; neurological symptoms included seizure, meningitis, encephalopathy, and headache; “with SARS‐CoV‐2” denotes children with SARS‐CoV‐2 infections, but admitted because of pilonidal sinus, subdural empyema, trauma, toxin ingestion, or bacterial lymphadenitis, who did not exhibit COVID‐19 symptoms.

Box 6 – Demographic characteristics and clinical history of children under 16 years of age managed by Sydney Children’s Hospital Network (SCHN) hospitals, 1 June – 31 October 2021

|

Characteristic |

VirtualKIDS‐CORT (random sample) |

Medical admission (no intensive care) |

Medical admission (with intensive care) |

P * |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of patients |

344 |

150 |

15 |

|

|||||||||||

|

Age (median), years, (IQR)† |

7.8 (3.8–11.4) |

2.0 (0.3–11.2) |

12.8 (10.4–15.5) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Age group† |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Under 6 months |

13 (4%) |

49 (33%) |

1 (7%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

6–23 months |

34 (10%) |

26 (17%) |

1 (7%) |

0.06 |

|||||||||||

|

2–4 years |

67 (19%) |

20 (13%) |

0 |

0.05 |

|||||||||||

|

5–11 years |

157 (46%) |

22 (15%) |

4 (27%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

12–15 years |

73 (21%) |

33 (22%) |

9 (60%) |

0.005 |

|||||||||||

|

Sex (boys) |

189 (55%) |

78 (52%) |

9 (60%) |

0.75 |

|||||||||||

|

Indigenous Australians |

13/334 (4%) |

8/147 (5%) |

1 (7%) |

0.43 |

|||||||||||

|

Vaccination status‡ |

|

|

|

0.36 |

|||||||||||

|

Unvaccinated |

313/319 (98%) |

135/136 (99%) |

12/13 (92%) |

|

|||||||||||

|

One dose |

3/319 (1%) |

1/136 (1%) |

1/13 (8%) |

|

|||||||||||

|

Two doses |

3/319 (1%) |

0/136 |

0/13 |

|

|||||||||||

|

Household contact§ |

285/306 (93%) |

128/138 (93%) |

12/14 (86%) |

0.44 |

|||||||||||

|

Premature birth (≤ 36 weeks’ gestation) |

13/209 (6%) |

17/123 (14%) |

2/13 (15%) |

0.037 |

|||||||||||

|

Weight > 95th percentile |

— |

27/139 (19%) |

8/14 (57%) |

0.004 |

|||||||||||

|

Any medical condition¶ |

62/337 (18%) |

52/149 (35%) |

9/15 (60%) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Asthma |

35 (56%) |

13 (25%) |

3 (33%) |

0.002 |

|||||||||||

|

Viral induced/recurrent wheeze |

0 |

6 (12%) |

0 |

0.017 |

|||||||||||

|

Other respiratory disease** |

1 (2%) |

7 (13%) |

1 (11%) |

0.038 |

|||||||||||

|

Cardiac disease |

4 (6%) |

6 (12%) |

2 (22%) |

0.20 |

|||||||||||

|

Neurological disease |

3 (5%) |

5 (10%) |

1 (11%) |

0.46 |

|||||||||||

|

Immunodeficiency |

1 (2%) |

3 (6%) |

0 |

0.51 |

|||||||||||

|

Renal disease |

0 |

1 (2%) |

1 (11%) |

0.07 |

|||||||||||

|

Liver disease |

0 |

2 (4%) |

0 |

0.32 |

|||||||||||

|

Diabetes |

0 |

1 (2%) |

0/8 |

0.49 |

|||||||||||

|

Other |

24 (39%) |

32 (62%) |

7 (78%) |

0.013 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COVID‐19 = coronavirus disease 2019; IQR = interquartile range; virtualKIDS‐CORT = virtualKIDS COVID‐19 outpatient response team. * virtualKIDS‐CORT v medical admission (with or without intensive care component), or medical admission (with intensive care component) v medical admission (without intensive care component) for characteristics not relevant to virtualKIDS‐CORT care; Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test (hospital length of stay) or Fisher exact test (other characteristics). P < 0.016 deemed statistically significant after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Data for a more comprehensive list of symptoms are included in the Supporting Information, table 1 and figure 1; post hoc multiple comparisons are reported in the Supporting Information, table 3. † At confirmation of positive SARS‐CoV‐2 test result (polymerase chain reaction‐confirmed). ‡ Dose 1 dates for two virtualKIDS‐CORT children unconfirmed; child excluded because dose 1 date was later than positive SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR test confirmation (two children who received virtualKIDS‐CORT care, one who was admitted to hospital [non‐intensive care]). § That is, child was a household contact of an infected person. ¶ Based on medical history review. ** Chronic lung disease (four children), obstructive sleep apnoea (two), type 1 laryngeal cleft (two), laryngomalacia (one). |

|||||||||||||||

Box 7 – Associations of demographic and clinical characteristics with medical admissions of children under 16 years of age with SARS CoV‐2 infections to Sydney Children’s Hospital Network (SCHN) hospitals, 1 June – 31 October 2021: univariate and multivariable analyses

|

|

|

Univariate analysis |

Multivariable analysis* |

||||||||||||

|

Characteristic |

Number of children |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Age group† |

509 |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Under 6 months |

|

23.2 (11.4–50.3) |

84.7 (22.6–379) |

||||||||||||

|

6–23 months |

|

4.80 (2.50–9.29) |

10.8 (3.32–38.5) |

||||||||||||

|

2–4 |

|

1.80 (0.93–3.44) |

5.38 (1.60–19.4) |

||||||||||||

|

5–11 |

|

1 |

1 |

||||||||||||

|

12–15 |

|

3.47 (1.99–6.16) |

8.12 (2.69–26.9) |

||||||||||||

|

Sex (boys) |

509 |

0.91 (0.63–1.33) |

0.82 (0.38–1.76) |

||||||||||||

|

Indigenous Australians |

496 |

1.45 (0.59–3.44) |

2.13 (0.34–12.9) |

||||||||||||

|

Household contact‡ |

458 |

0.86 (0.42–1.85) |

0.62 (0.14–2.75) |

||||||||||||

|

Premature birth (≤ 36 weeks’ gestation) |

345 |

2.45 (1.18–5.25) |

0.52 (0.14–1.91) |

||||||||||||

|

Any medical condition |

501 |

2.63 (1.73–4.00) |

7.42 (3.08–19.3) |

||||||||||||

|

Asthma/viral induced wheeze§ |

123 |

0.38 (0.18–0.78) |

NA |

||||||||||||

|

Other respiratory disease |

123 |

9.21 (1.61–174) |

NA |

||||||||||||

|

Cardiac disease |

123 |

2.19 (0.65–8.59) |

NA |

||||||||||||

|

Clinical features |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Fever |

378 |

14.6 (8.83–24.7) |

19.0 (8.41–47.6) |

||||||||||||

|

Cough |

396 |

2.73 (1.78–4.22) |

2.82 (1.18–7.03) |

||||||||||||

|

Rhinorrhoea |

395 |

1.48 (0.99–2.23) |

0.56 (0.24–1.28) |

||||||||||||

|

Fatigue/malaise |

390 |

1.80 (1.18–2.77) |

1.27 (0.56–2.91) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval; NA = not available (not included in multivariable analysis because case numbers were low). * All included variables are listed in the table. Goodness of fit statistics: Nagelkerke R2 = 0.64; McFadden pseudo‐R2 = 0.47; prediction percentage in null model, 67.6%; in test model, 85.1%. † At confirmation of positive SARS‐CoV‐2 test result (polymerase chain reaction‐confirmed). ‡ That is, child was a household contact of an infected person. § Combined because sample size for viral induced wheeze was small (four). |

|||||||||||||||

Received 4 January 2022, accepted 18 May 2022

- Phoebe Williams1,2

- Archana Koirala3,4

- Gemma L Saravanos5

- Laura K Lopez4

- Catherine Glover4

- Ketaki Sharma3,4

- Tracey Williams1,6

- Emma Carey5

- Nadine Shaw7

- Emma Dickens7

- Neela Sitaram7

- Joanne Ging7

- Paula Bray5,6

- Nigel W Crawford8,9

- Brendan McMullan9,10

- Kristine Macartney3,4

- Nicholas Wood1,3

- Elizabeth L Fulton1,6

- Christine Lau7

- Philip N Britton1,3

- 1 The Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW

- 2 Sydney Children's Hospital at Randwick, Sydney, NSW

- 3 The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 4 National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance, the Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW

- 5 Kids Research, the Sydney Children's Hospitals Network, Sydney, NSW

- 6 Home in the Hospital service, the Sydney Children's Hospitals Network, Sydney, NSW

- 7 virtualKIDS, the Sydney Children's Hospitals Network, Sydney, NSW

- 8 Surveillance of Adverse Events Following Vaccination in the Community (SAEFVIC), Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, VIC

- 9 Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

- 10 The University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW

Paediatric Active Enhanced Disease Surveillance (PAEDS) is funded by the Australian Department of Health to conduct surveillance of COVID‐19 and its multisystem inflammatory complications in children. The Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network (SCHN) hospitals also receive funding from the NSW Ministry of Health.

We acknowledge the significant contributions by the SCHN departments of general medicine, paediatric intensive care, immunology, rheumatology, and infectious diseases and infection prevention and control for the high quality clinical care they have provided to the children described in this study. We also acknowledge the many clinicians (nursing, medical and allied health) who contributed, and the SCHN virtualKIDS COVID‐19 positive outpatient response team. Finally, we acknowledge the NSW PAEDS surveillance nurses Nicole Dinsmore, Nicole Kerly, Shirley Wong, Katherine Meredith, and Laura Rost for their assistance with case identification, data collection, and involvement in the care of the children described in this article.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. World Health Organization. COVID‐19 weekly epidemiological update, edition 98. 29 June 2022. https://www.who.int/docs/default‐source/coronaviruse/situation‐reports/20220629_weekly_epi_update_98.pdf?sfvrsn=158c6adc_8&download=true (viewed July 2022).

- 2. Tosif S, Ibrahim LF, Hughes R, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in Victorian children at a tertiary paediatric hospital. J Paediatr Child Health 2022; 58: 618‐623.

- 3. Swann O, Pollock L, Holden K, et al; ISARIC4 Investigators. Comparison of children and young people admitted with SARS‐CoV‐2 across the UK in the first and second pandemic waves: prospective multicentre observational cohort study. 17 Sept 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/isaric‐comparison‐of‐children‐and‐young‐people‐admitted‐with‐sars‐cov‐2‐across‐the‐uk‐in‐the‐first‐and‐second‐pandemic‐waves‐prospective‐multicentr (viewed Dec 2021).

- 4. Smith C, Odd D, Harwood R, et al. Deaths in children and young people in England after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection during the first pandemic year. Nat Med 2022; 18: 185‐192.

- 5. Beaney T, Neves AL, Alboksmaty A, et al. Trends and associated factors for Covid‐19 hospitalisation and fatality risk in 2.3 million adults in England. Nat Commun 2022; 13: 2356.

- 6. Viner RM, Ward JL, Hudson LD, et al. Systematic review of reviews of symptoms and signs of COVID‐19 in children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child 2021; 106: 802‐807.

- 7. Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID‐19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr 2020; 109: 1088‐1095.

- 8. Webb NE, Osburn TS. Characteristics of hospitalized children positive for SARS‐CoV‐2: experience of a large center. Hosp Pediatr 2021; 11: e133‐e141.

- 9. Kushner LE, Schroeder AR, Kim J, Mathew R. “For COVID” or “with COVID”: classification of SARS‐CoV‐2 hospitalizations in children. Hosp Pediatr 2021; 11: e151‐e156.

- 10. Koirala A, Gidding HF, Vette K, Macartney K; PAEDS Serosurvey Group. The seroprevalence of SARS‐CoV‐2‐specific antibodies in children, Australia, November 2020 – March 2021. Med J Aust 2022; 217: 43‐45. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/217/1/seroprevalence‐sars‐cov‐2‐specific‐antibodies‐children‐australia‐november‐2020

- 11. NSW Government. Public health orders relating to Delta outbreak restrictions. Updated 11 Oct 2021. https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/information/covid19‐legislation/temporary‐movement‐gathering‐restrictions (viewed July 2022).

- 12. Meherali S, Punjani N, Louie‐Poon S, et al. Mental health of children and adolescents amidst COVID‐19 and past pandemics: a rapid systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 3432.

- 13. Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB, et al. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low‐income and middle‐income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2020; 8: e901‐e908.

- 14. Molteni E, Sudre CH, Canas LS, et al. Illness duration and symptom profile in symptomatic school‐aged children tested for SARS‐CoV‐2. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2021; 5: 708‐718.

- 15. NSW Health. Virtual hospital providing care to COVID positive children. 30 Sept 2021. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/virtualcare/Pages/case‐studies‐virtual‐kids.aspx (viewed Dec 2021).

- 16. Green P. Risks to children and young people during covid‐19 pandemic. BMJ 2020; 369: m1669.

- 17. Zimmermann P, Curtis N. Why is COVID‐19 less severe in children? A review of the proposed mechanisms underlying the age‐related difference in severity of SARS‐CoV‐2 infections. Arch Dis Child 2021; 106: 429‐439.

- 18. Bundle N, Dave N, Pharris A, et al. COVID‐19 trends and severity among symptomatic children aged 0–17 years in 10 European Union countries, 3 August 2020 to 3 October 2021. Eurosurveillance 2021; 26: 2101098.

- 19. Booth A, Reed AB, Ponzo S, et al. Population risk factors for severe disease and mortality in COVID‐19: a global systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0247461.

- 20. Swann OV, Holden KA, Turtle L, et al; ISARIC4C Investigators. Clinical characteristics of children and young people admitted to hospital with covid‐19 in United Kingdom: prospective multicentre observational cohort study. BMJ 2020; 370: m3249.

- 21. Skevaki C, Karsonova A, Karaulov A, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and COVID‐19 in asthmatics: a complex relationship. Nat Rev Immunol 2021; 21: 202‐203.

- 22. Colvin JM, Muenzer JT, Jaffe DM, et al. Detection of viruses in young children with fever without an apparent source. Pediatrics 2012; 130: e1455‐e1462.

- 23. Halasa NB, Olson SM, Staat MA, et al; Overcoming Covid‐19 Investigators. Maternal vaccination and risk of hospitalization for Covid‐19 among infants. N Engl J Med 2022; 387: 109‐119.

- 24. NSW Health. COVID‐19 vaccination in NSW. 2021. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Infectious/covid‐19/vaccine/Pages/default.aspx (viewed June 2022).

- 25. Paediatric Active Enhanced Disease Surveillance (PAEDS) Network. COVID‐19, Kawasaki disease (KD) and PIMS‐TS in children [media release]. 15 May 2020. https://paeds.org.au/covid‐19‐kawasaki‐disease‐kd‐and‐pims‐ts‐children (viewed Dec 2021).

- 26. Wurzel D, McMinn A, Hoq M, et al. Prospective characterisation of SARS‐CoV‐2 infections among children presenting to tertiary paediatric hospitals across Australia in 2020: a national cohort study. BMJ Open 2021; 11: e054510.

- 27. Ibrahim LF, Tham D, Chong V, et al. The characteristics of SARS‐CoV‐2‐positive children who presented to Australian hospitals during 2020: a PREDICT network study. Med J Aust 2021; 215: 217‐221. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2021/215/5/characteristics‐sars‐cov‐2‐positive‐children‐who‐presented‐australian‐hospitals

Summary

Objectives: To describe the severity and clinical spectrum of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in children during the 2021 New South Wales outbreak of the Delta variant of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2).

Design, setting: Prospective cohort study in three metropolitan Sydney local health districts, 1 June – 31 October 2021.

Participants: Children under 16 years of age with positive SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid test results admitted to hospital or managed by the Sydney Children’s Hospital Network (SCHN) virtual care team.

Main outcome measures: Age-specific SARS-CoV-2 infection frequency, overall and separately for SCHN virtual and hospital patients; rates of medical and social reason admissions, intensive care admissions, and paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 per 100 SARS-CoV-2 infections; demographic and clinical factors that influenced likelihood of hospital admission.

Results: A total of 17 474 SARS-CoV-2 infections in children under 16 were recorded in NSW, of whom 11 985 (68.6%) received SCHN-coordinated care, including 459 admitted to SCHN hospitals: 165 for medical reasons (1.38 [95% CI, 1.17–1.59] per 100 infections), including 15 admitted to intensive care, and 294 (under 18 years of age) for social reasons (2.45 [95% CI, 2.18–2.73] per 100 infections). In an analysis that included all children admitted to hospital and a random sample of those managed by the virtual team, having another medical condition (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 7.42; 95% CI, 3.08–19.3) was associated with increased likelihood of medical admission; in univariate analyses, non-asthmatic chronic respiratory disease was associated with greater (OR, 9.21; 95% CI, 1.61–174) and asthma/viral induced wheeze with lower likelihood of admission (OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.18–0.78). The likelihood of admission for medical reasons declined from infancy to 5–11 years, but rose again for those aged 12–15 years. Sex and Indigenous status did not influence the likelihood of admission.

Conclusion: Most SARS-CoV-2 infections (Delta variant) in children were asymptomatic or associated with mild disease. Hospitalisation was relatively infrequent, and most common for infants, adolescents, and children with other medical conditions. More children were hospitalised for social than for medical reasons.