Modelling suggests that elimination could have been achieved if Victoria had gone into stage 4 lockdown immediately from 9 July

Victoria is the unlucky state in a lucky country. Australian states and territories, other than New South Wales, have achieved elimination of community transmission of the sudden acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2): 28 days of no locally acquired cases where the source is unknown; twice the maximum incubation period.

The situation in NSW is mixed. On one hand, NSW had ongoing case notifications of 10–20 per day in the month to mid‐August 2020, arising largely from imported cases from Victoria. On the other hand, on 16 July there had only been three locally acquired cases of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection with no known source in the preceding 28 days, suggesting NSW was on the cusp of elimination.1 If NSW successfully contains the current outbreak, it may resume its prior trajectory towards the elimination of local transmission, leaving Victoria isolated as the only state with community transmission. As of late August, Queensland is also experiencing community transmission — possibly ending its elimination status (28 days of no locally acquired cases where the source is unknown), subject to investigation of the new cases.

It seems unlikely that states and territories that have eliminated local transmission will relinquish their status by freely opening borders and engaging with Victoria (and NSW if community transmission remains). Indeed, on 17 August the Queensland Premier stated: “Let me make it very clear, we will always put Queenslanders first and … we do not have any intentions of opening any borders while there is community transmission active in Victoria and in New South Wales”.2 Australia proceeding with two separate systems (six or seven states and territories having eliminated the virus, one or two not) is a significant concern.

There are three general strategic policy responses to the challenge of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): elimination, suppression, and mitigation (or herd immunity). No response is free of economic, social and health harms; rather, it is about minimising harm. Society has largely rejected a mitigation response because of concerns about the likely high morbidity and mortality arising from such a response. On 24 July, the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee recommended “that the goal for Australia is to have no community transmission of COVID‐19”,3 and on the same day Prime Minister Scott Morrison accepted and affirmed this recommendation, stating “The goal of that is obviously, and has always been no community transmission”.4 Unfortunately, this first clear statement that Australia's goal is to eliminate community transmission was late in coming, as the Victorian outbreak was already in full swing, with case numbers peaking at a 5‐day average of about 500 per day from 29 July to 5 August, resulting in a stage 4 lockdown in metropolitan Melbourne from 6 pm on 2 August.

Elimination strategy

We know from New Zealand (population, 5.0 million)5 and Taiwan (23.8 million)6 that elimination of community transmission is achievable in island jurisdictions, with NZ having no community transmission for 102 days until 11 August. The advantage of elimination is that despite international border closures or strict quarantine, citizens can go about life with a near‐normal functioning of their society and economy.

Elimination presents challenges. First, there is the extra effort to achieve it, and the fact that aiming to achieve elimination does not guarantee success. Second, having achieved elimination, there is the constant risk of the virus re‐entering due to quarantine breaches (eg, the current outbreak in NZ).

How frequently a COVID‐19‐free jurisdiction with tight border controls will retain elimination status is unclear, although we know that NZ lasted 102 days with no community transmission and that Western Australia, Northern Territory, South Australia, Australian Capital Territory, Queensland and Tasmania achieved over 100 days without a locally acquired case with no known source (although the status of Queensland is unclear as of early September).

Was elimination achievable with a 6‐week stage 3 lockdown as implemented in Victoria from 9 July, or a more stringent lockdown?

Lockdowns are effective for COVID‐19 pandemic control.7,8 Our case for an explicit elimination strategy in Victoria at lockdown commencement in early July was that given Victoria was going into a lockdown for 6 weeks, there was probably only a marginal extra cost of “going hard” with a rigorous public health response that increased the probability of achieving elimination. But was elimination achievable within 6 weeks?

We examined four policy scenarios using an agent‐based model, a type of microsimulation of individuals. The model accurately reflects the prior experience of both NZ and Australia ( https://github.com/JTHooker/COVIDModel), and here we adapted it to Victoria (including the case counts up to 14 July; see Supporting Information for details). The four policy approaches, all simulated from 9 July 2020, were:

- Standard: reflecting the first Australian stage 3 lockdown (calibrated to case numbers as described at https://github.com/JTHooker/COVIDModel), with key parameters including 85% of people observing physical distancing; those observing physical distancing doing so 85% of the time; 30% of adult workers being essential workers; 93% of people asked to isolate doing so; 20% uptake of the COVIDSafe app; but no closure of schools and no mask wearing.

- Standard with masks at 50%: Standard, plus 50% of people wearing masks in crowded indoor environments.

- Stringent with masks at 50%: Standard with masks at 50%, plus schools closed and essential workers restricted to 20% of workers.

- Stringent with masks at 90%: Stringent, with mask use increased to 90% (ie, close to stage 4, which was implemented in Melbourne from 6 pm on 2 August after the 5‐day moving average case numbers increased from 300 to 500 in the first 3 weeks of stage 3).

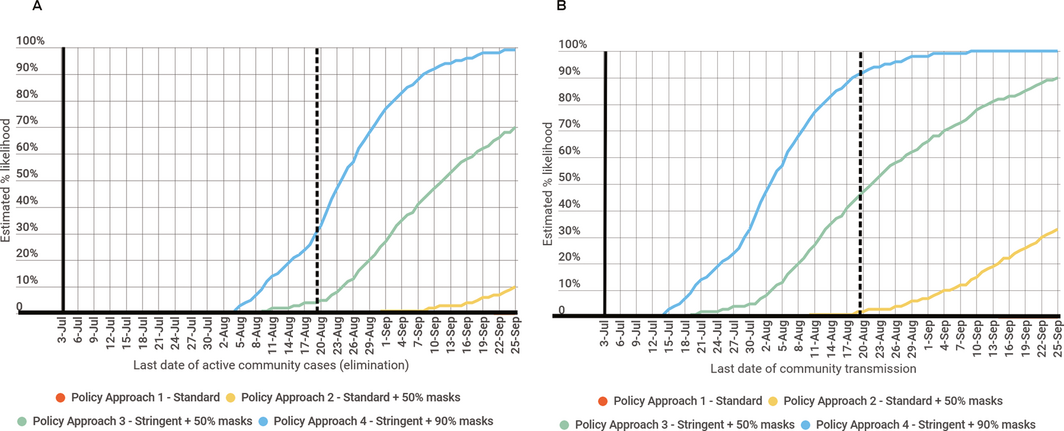

Box 1 shows the percentage likelihood of elimination in Victoria, defined as the date of clearance of infection by the last case, and the date of last acquisition of infection. The model is omniscient about infectious status; in the real world, based on a definition of 28 days of no cases, elimination would occur about 2 weeks after the clearance dates shown in Box 1, A.

Under the “standard” policy approach (ie, equivalent to stage 3 without masks), there was no chance that all infected people would have cleared their SARS‐CoV‐2 infection by 19 August (6 weeks after lockdown commenced; Box 1, A). The probabilities for the other three policy approaches achieving elimination 6 weeks after implementation (Box 1, A) were 0% for “standard with masks at 50%”; about 4% for “stringent with masks at 50%”; and 30% for “stringent with masks at 90%”. The probabilities of the last actual infection occurring by 19 August were more encouraging at 0%, 1%, 45% and 90%, respectively (Box 1, B).

Of particular note, given that the stage 3 lockdown imposed on 9 July failed because caseloads increased to an average of 500 per day, in our simulations 48% of the 1000 iterations of the “standard” scenario (stage 3, no masks) and 22% of the 1000 iterations for “standard with masks at 50%” had peaks in the first 3 weeks in excess of 400 per day. This is consistent with what eventuated, and further speaks (in hindsight) to the desirability of entering a stage 4 lockdown on 9 July; the “stringent with masks at 90%” scenario had no instances of peak cases greater than 400 per day in the first 3 weeks.

Undertaking simulation modelling of SARS‐CoV‐2 policy options is challenging and the uncertainties are still considerable even when using the best estimates available. Nevertheless, our results lend weight to the proposition that elimination was achievable if Victoria had gone into stage 4 lockdown with mandatory wearing of masks immediately from 9 July.

A ten‐point plan to maximise the chance of elimination in Victoria

Box 2 lists enhancements to the stay‐at‐home orders of the 9 July lockdown. The first and critical point was leadership. As above, we did get a clear statement of an elimination goal from the Chief Health Officers (who comprise the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee membership) and Prime Minister Scott Morrison on 24 July, but with the benefit of hindsight it was perhaps too late. Target‐setting is still not occurring (eg, a target number of cases per day could be set for when we step out of stage 4 under both elimination and suppression strategy options). Moreover, an expert advisory group on elimination was not convened, limiting the capacity for an optimal evidence‐informed policy response.

Nevertheless, since the 9 July lockdown, progress with other aspects of the ten‐point plan has been made with the closure of schools, mandatory mask wearing, and commitments to improve contact tracing capacity.

Conclusion

We argued in the preprint version of this article on 17 July that Melbourne and Victoria should not waste the opportunity that the (then) 6‐week lockdown presented and go hard and early. By learning from the lessons on social and preventive measures to lower SARS‐CoV‐2 transmissibility,7,8,12,14 and specifically the lessons from NZ,3 Taiwan and the six Australian jurisdictions that have achieved elimination, Victoria could have increased its chances of also eliminating community transmission.

Our work and that of others who have independently considered the alternatives consistently demonstrates that elimination was possible, and if achieved would have been optimal for health and for the economy in the long term.15,16,17 In this article, we modelled the situation as at mid‐July — we are now updating modelling under the current situation.

Authors’ note: This Perspective was submitted to the MJA on 16 July 2020 and published as a preprint on 17 July.9 The revised version, submitted on 23 August, retains the simulation modelling of the original but the uncertainty of inputs was updated to include uncertainty other than stochastic uncertainty. Our aim was rapid modelling to estimate the probability of virus elimination during the planned 6‐week stage 3 lockdown that Victoria had just commenced. The revised version was also published as a preprint on mja.com.au on 4 September, following full peer review and prior to typesetting, pagination and proofreading.

Box 1 – Percentage likelihood of elimination of community transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in Victoria, by date of clearance of last active infection (A) and date of acquisition of last infection (B)*

* Across 1000 Monte Carlo simulations in an agent‐based SEIR (susceptible, exposed, infectious, recovered) model. The vertical dashed line is the date 6 weeks after implementation of the lockdown policies. Compared with modelling published in the preprint version of this article,9 the only change here is the inclusion of additional parameter uncertainty in addition to stochastic uncertainty (see Supporting Information), resulting in increased sloping in the curves due to a wider range of potential parameter values (ie, the time distribution to elimination is wider).

Box 2 – A ten‐point plan to maximise the chance of successful elimination of community transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2 in Victoria, based on the planned 6‐week lockdown from 9 July 2020 (as published on 17 July 2020)9

- Strong and decisive leadership with strategic clarity. An explicit goal of elimination should be articulated, learning from the New Zealand experience (Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, government ministers and senior officials).10 A clear set of targets for loosening of policies needs to be articulated, so citizens know what is likely to happen and when.

- Convene an advisory group of experts in the elimination strategy and SARS‐CoV‐2 public health response, reporting weekly to the Victorian Chief Health Officer, with the agenda, papers and minutes made publicly available.

- Close all schools. Although children do not usually suffer severe illness from SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, the virus still transmits between children and staff in schools.11 Accordingly, schools need to close until such time as the daily rate of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection without a known source falls beneath a target set by the Chief Health Officer.

- Tighten the definition of essential shops to remain open. Supermarkets and chemists need to remain open. However, department stores and hardware stores should be closed. A staged re‐opening based on set target levels of daily numbers of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection without a known source should then be implemented, so long as mask wearing by both staff and patrons is mandatory, along with hand sanitiser use on entry and exit from stores.

- Require mask wearing by Melbourne residents in indoor environments where 1.5 m physical distancing cannot be ensured, such as supermarkets and (especially) public transport. While no panacea, the wearing of masks reduces the chance of infected people spreading the virus.12

- Tighten the definition of essential workers and work. There is currently a loose definition of who is an essential worker and what is essential work. This needs urgent tightening; for example, as per the NZ definitions used in their level 4 lockdown.13

- Require mask wearing by essential workers whenever they are in close contact with people other than those in their immediate household.

- Ensure financial and other supports to businesses, community and other groups most affected by more stringent stay‐at-home and lockdown requirements, and provide enhancements, targeted where warranted, to programs such as JobKeeper and JobSeeker.

- Further strengthen contact tracing to ensure the majority of notifications (and their close contacts) are interviewed within 24 hours of the index case notification and placed in isolation if necessary. The use of smart phone and digital adjuncts needs to be improved, be that for initial contact tracing (eg, the COVIDSafe app, or a South Korean‐style use of telecommunications data) or monitoring of adequacy of isolation (eg, text message follow‐up, GPS monitoring, or electronic bracelets).

- Extend suspension of international arrivals into Victorian quarantine and divert resources. To allow a stronger focus on elimination within Victoria, extend the suspension of international arrivals to Victoria. Quarantine capacity can be redeployed for isolation of Melbourne residents infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 (and potentially high risk close contacts) if they do not have satisfactory home environments for self‐isolation.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. New South Wales Government. COVID‐19. https://www.nsw.gov.au/covid-19 (viewed Aug 2020).

- 2. Masige S. Queensland won't open its borders to Victoria and New South Wales until there is zero community transmission, the premier says. Business Insider Australia 2020; 17 Aug. https://www.businessinsider.com.au/queensland-border-closure-victoria-new-south-wales-community-transmissions-2020-8 (viewed Sept 2020).

- 3. Australian Health Protection Principal Committee. Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) statement on strategic direction. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health, 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/news/australian-health-protection-principal-committee-ahppc-statement-on-strategic-direction (viewed Sept 2020).

- 4. Prime Minister of Australia. Press conference – Australian Parliament House, ACT. 24 July 2020. https://www.pm.gov.au/media/press-conference-australian-parliament-house-act-24jul20 (viewed Sept 2020).

- 5. Baker MG, Kvalsvig A, Verrall AJ. New Zealand's COVID‐19 elimination strategy. Med J Aust 2020; 213: 198–200. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/213/5/new-zealands-covid-19-elimination-strategy

- 6. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World population prospects 2019: data booklet. New York: UN, 2019.

- 7. Flaxman S, Mishra S, Gandy A, et al. Estimating the effects of non‐pharmaceutical interventions on COVID‐19 in Europe. Nature 2020; 584: 257–261.

- 8. Hsiang S, Allen D, Annan‐Phan S, et al. The effect of large‐scale anti‐contagion policies on the COVID‐19 pandemic. Nature 2020; 584: 262–267.

- 9. Blakely T, Thompson J, Carvalho N, et al. Maximizing the probability that the 6‐week lock‐down in Victoria delivers a COVID‐19 free Australia. Med J Aust 2020; https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/maximizing-probability-6-week-lock-down-victoria-delivers-covid-19-free-australia [Preprint, 17 July 2020].

- 10. New Zealand Government Ministry of Health. Aotearoa/New Zealand's COVID‐19 elimination strategy: an overview. Wellington, NZ Ministry of Health, 2020. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/pages/aotearoa-new_zealands_covid-19_elimination_strategy-_an_overview17may.pdf (viewed Aug 2020).

- 11. Li X, Xu W, Dozier M, et al. The role of children in transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2: a rapid review. J Glob Health 2020; 10(10): 011101.

- 12. Bi Q, Wu Y, Mei S, et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID‐19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20: 911–919.

- 13. New Zealand Government. Unite against COVID‐19. https://covid19.govt.nz/ (viewed Aug 2020).

- 14. Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person‐to-person transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2 and COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet 2020; 395: 1973–1987.

- 15. Daly J. COVID‐19: the endgame and how to get there. Melbourne: Grattan Institute, 2020.

- 16. Group of Eight Australia. COVID‐19 roadmap to recovery: a report for the nation. Canberra: Group of Eight, 2020. https://go8.edu.au/research/roadmap-to-recovery (viewed Aug 2020).

- 17. Chang S, Harding N, Zachreson C, et al. Modelling transmission and control of the COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia. arXiv 2020; 2003.10218v3.

No relevant disclosures.