Clinical record

A 34-year-old man presented to a small rural emergency department at 21:45, arriving by private car from a bush campsite some 45 minutes' drive away. An empty “stubbie” beer bottle had been recapped and thrown on the fire. It subsequently exploded, showering glass fragments onto surrounding people, one of whom sustained a small penetrating neck injury (PNI) with a piece of glass lodging in his anterior neck.

On arrival at the hospital, the patient had removed the glass and was clutching his neck with paper towels, describing a feeling of blood in the back of his throat, with associated haemoptysis.

He had a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15, with normal vital signs, and was found to have a 1 cm wound just above his cricoid cartilage slightly to the right of midline. There was minimal active bleeding externally, but air occasionally bubbled from the wound and surgical emphysema was palpable on the right side of his neck. He was most comfortable slightly head down on his right side, and was maintaining O2 saturation of 99% in room air, with no clinical evidence of pneumothorax.

In consultation with Adult Retrieval Victoria, the attending anaesthetic-trained rural general practitioner decided to proceed to rapid sequence intubation (RSI) with an oral endotracheal tube (ETT) before evacuation to a tertiary centre.

With assistance from the nursing staff and a second anaesthetic-trained rural GP, the patient was pre-oxygenated with deep spontaneous breaths and a successful RSI under direct laryngoscopy was performed. For easier insertion, a size 7.5 cuffed ETT was placed. Blood was present on the vocal cords, but the oropharynx was clear.

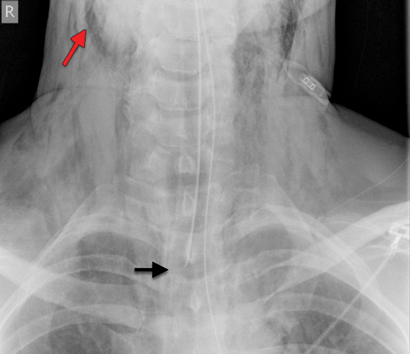

Mechanical ventilation was carried out initially with a portable unit (Weinmann Medumat Standard-a), on minute volume cycle with a minimum available pressure of 20 cm H2O. Subsequent chest x-ray showed extensive surgical emphysema (Figure) and air mediastinum, at which point he was moved to the operating theatre to allow lower pressure ventilation using an anaesthetic ventilator. The ETT was shifted further down the trachea to tamponade the site of traumatic injury, and reduce bleeding and tissue emphysema.

Assisted ventilation at the hospital continued until 01:38, when the retrieval team arrived by road ambulance some 4 hours later.

He was transferred by road ambulance to the tertiary hospital, arriving at 04:22, where investigation with computed tomography (CT) angiography excluded any vascular injury. A surgical tracheostomy and tracheal repair was undertaken at 12:40 later that day. He spent over 24 hours in the intensive care unit on mechanical ventilation before making a full recovery.

Penetrating neck injury is commonly related to violence in countries such as the United States and South Africa,1 but it is rarer in Australia. This case report highlights the challenges and importance of initial management of a PNI in an isolated medical service, and the importance of health education around campfire safety.

The initial management of a PNI in a patient with a patent airway and who is haemodynamically stable with no signs of vascular injury is generally now considered to involve CT vascular imaging and selective surgical management.2,3 In an isolated medical facility without access to these services, management options are more limited. Initial treatment involves management of actual and potential airway complications together with stabilisation of vascular injury and resultant haemorrhage, with a plan for early evacuation to an appropriate tertiary facility for definitive care.

Our patient was haemodynamically stable and clinically had no obvious evidence of a significant vascular injury. The penetrating glass fragment was described as small, although not seen by the medical staff as the patient had removed it before arrival. The ongoing haemoptysis and palpable surgical emphysema suggested airway injury, and potential risks associated with haematoma formation and airway obstruction during transport led to the decision to perform rapid sequence endotracheal intubation. This is thought to be the safest initial airway management when anatomical structures are preserved,2,4 although definitive surgical airway management would be required at the tertiary centre.

Incorrect ETT placement, inadequate seal, or excessive ventilator pressure, may lead to acute deterioration where tracheal injury exists. This is particularly important in a remote medical setting, where considerable delay can occur before transport to an appropriate tertiary care facility, which could have become a critical issue in our case had the patient not been haemodynamically stable.

Despite standard transport immobilisation protocols, the literature recommends that cervical spine immobilisation is not required unless focal neurological deficits are present.2 Penetrating neck injuries (particularly stabbing) rarely cause spinal cord injury,5 and cervical collars can impede airway visualisation or evidence of other injuries. Our patient had no clinical evidence of spinal cord injury and no mechanism of injury to suggest one, so a cervical collar was not applied, making it easier to intubate as well as to monitor and assess the injury site.

Many outdoor recreation activities involving campfires occur in isolated environments, with limited access to medical and emergency services. In such situations, burns are an increasing concern,6 either from falls or exploding containers.7 This case demonstrates the additional risk of projectiles from exploding containers irresponsibly placed into fires. Although common sense dictates that it is risky to throw sealed containers into open fires, anecdotally it is often done when alcohol consumption is combined with open fires in a relaxed bush environment.

This case suggests that appropriate initial management of PNIs in an isolated rural setting can include careful endotracheal intubation until later surgical management with a definitive surgical airway. In addition, it reinforces the public health message that responsible behaviour reduces risk — particularly when setting an example and providing health education messages to the next generation. This case was unusual, but the clinical and public health lessons it provides are perhaps generalisable.

Lessons from practice

- Management of penetrating neck injury in an isolated setting involves stabilisation and endotracheal intubation.

- Cervical spine immobilisation is not required with penetrating neck injury unless focal neurological deficits are present.

- Rapid sequence intubation is a useful skill for general practitioners to have when working in a rural setting.

- Graham M Slaney1

- Anthony Guiney2

- Yvonne Hezel3

- Philip Weinstein4

- 1 Mansfield Medical Clinic, Mansfield, VIC.

- 2 Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, VIC.

- 3 Mansfield District Hospital, Mansfield, VIC.

- 4 University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Demetriades D, Skalkides J, Sofianos C, et al. Carotid artery injuries: experience with 124 cases. J Trauma 1989; 29: 91-94.

- 2. Brywczynski JJ, Barrett TW, Lyon JA, Cotton BA. Management of penetrating neck injury in the emergency department: a structured literature review. Emerg Med J 2008; 25: 711-715.

- 3. Asensio JA, Valenziano CP, Falcone RE, Grosh JD. Management of penetrating neck injuries. The controversy surrounding zone II injuries. Surg Clin North Am 1991; 71: 267-296.

- 4. Mandavia DP, Qualls S, Rokos I. Emergency airway management in penetrating neck injury. Ann Emerg Med 2000; 35: 221-225.

- 5. Lustenberger T, Talving P, Lam L, Kobayashi L, et al. Unstable cervical pine fracture after penetrating neck injury: a rare entity in an analysis of 1,069 patients. J Trauma 2011; 70: 870-872.

- 6. Maguiña P, Palmieri TL, Curri T, et al. The circle of safety: a campfire burn prevention campaign expanding nationwide. J Burn Care Rehabil 2004; 25: 124-127.

- 7. Yarbrough DR. Burns due to aerosol can explosions. Burns 1998; 24: 270-271.

Tim JohnLeeuwenburg

Such cases are not uncommon in rural Australia and require an appropriate, staged response to airway management. Whilst transport to definitive care is the gold standard, the isolated rural practitioner (and his/her patient) may well be required to secure the airway despite the obstacles of (a) infrequency of performance, diluting skill mix (ii) unfamiliarity of the rural resuscitation team and (iii) paucity of available equipment, not least access to awake fibreoptic techniques or imaging.

Thankfully, in this era of Web2.0 connectivity and social media, the advent of FOAMed resources (free open access medical education) mean that the rural practitioner is but a few clicks away from a veritable cornucopia of expert learning resources.

In recent years, many rural doctors in Australia have availed themselves of these resources, ensuring that difficult and failed airway plans are practiced, standardised and articulated to team members, that equipment to manage the difficult airway is available in all areas where anaesthesia is practiced, regardless of location and that valuable adjuncts (not least the technique of apnoeic diffusion oxygenation, airway topicalising, dissociative anaesthesia with ketamine and videolaryngoscopy) are additional weapons int he airway armamentarium of rural clinicians.

I would be interested in the authors perspective on the minimum requirements for training and equipment for rural GP-anaesthetists, as well as commentary on recent developments in airway management from FOAMed, that can help rural clinicians to deliver "quality care, out there"

Refs:

Leeuwenburg TJ. (2012) Access to difficult airway equipment and training for rural GP-anaesthetists in Australia: results of a 2012 survey. Rural and Remote Health 12: 2127. (Online) 2012. Available: http://www.rrh.org.au

Leeuwenburg T. (2015) Airway Management of the Critically Ill Patient: Modifications of Traditional Rapid Sequence Induction and Intubation. Critical Care Horizons 2015; 1: 1-10. Available from: http://www.criticalcarehorizons.com/airway-management-of-the-critically-ill-patient/

Competing Interests: No relevant disclosures

Dr Tim JohnLeeuwenburg

Kangaroo Island Medical Clinic