Clinical record

|

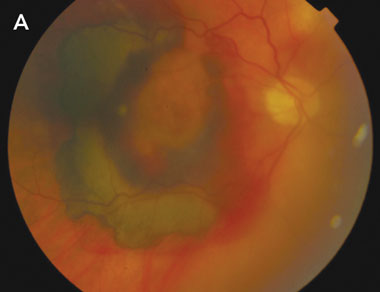

A: Fundus photograph of the right eye at presentation, showing macular subretinal and intraretinal haemorrhage. The mild haziness of the photograph is indicative of vitreous haemorrhage. |

|

|

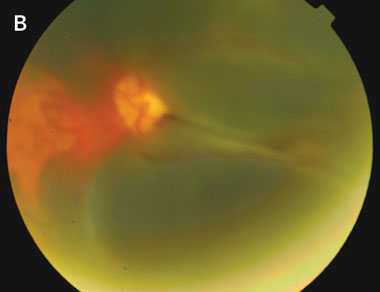

B: Fundus photograph of the left eye at the time of presentation of visual loss in this eye. Extensive subretinal haemorrhage is seen in the macula. Again, the haziness of the photograph is indicative of vitreous haemorrhage. |

This report highlights a potential interaction between a commonly used anticoagulant, warfarin, and an increasingly common ocular condition — AMD. The risk of AMD increases with age, with prevalence reaching 20% of people aged over 75 years in white populations.1 Neovascular (“wet”) AMD accounts for 10%–20% of cases,2 and for 80%–90% of patients who become legally blind from AMD.3 Peripheral vision is typically retained, and most patients are able to maintain a degree of functional independence.

Development of large subretinal and vitreous haemorrhages in neovascular AMD is uncommon. Treatment options are limited and, even with surgical intervention, visual outcomes are in the range of light perception to counting fingers only, with significant loss of paracentral and peripheral vision.4 The functional effects are therefore profound.

Previous studies have demonstrated an association between the use of anticoagulant medication, particularly warfarin, and large intraocular haemorrhages among patients with neovascular AMD.5,6 The largest of these, a retrospective case–control study comprising 100 patients, found that those with massive intraocular haemorrhage were 11.6 times more likely to be taking anticoagulant medication.6 Among these patients, INR ranged from 3.0 to 4.0. Patients with massive haemorrhage were twice as likely to be taking aspirin, although the significance of this finding is less certain, as the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval was less than 1. No patient was taking anticoagulants and aspirin concurrently.6

In our patient, the role of concurrent aspirin therapy is unclear, as there is no evidence in the literature to support or refute the hypothesis that concurrent antiplatelet therapy may have contributed to the development of haemorrhage. However, both instances of haemorrhage were noted to occur at times when his INR was high compared with those recorded over the previous 12 months. Our patient was taking aspirin at all times during this period. Although it is possible that intraocular haemorrhage may have occurred purely as a result of his underlying neovascular AMD, the temporal relationship between the development of the haemorrhages and the high INRs strengthens the case for the implication of warfarin therapy as a contributing factor. Application of the Naranjo probability scale7 indicates that this adverse drug event was probable (Naranjo score, + 5).

The association between anticoagulant therapy and intraocular haemorrhage is of key importance for several reasons. Firstly, massive intraocular haemorrhage is an important diagnosis to consider in an anticoagulated patient who presents with loss of vision, and who has a background of neovascular AMD. Secondly, patients with neovascular AMD in one eye are at risk of developing neovascular AMD in the second eye,8 and therefore at risk of developing large intraocular haemorrhages in both eyes if long-term anticoagulation is continued.

Lessons from practice

Patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD) have a small but significant risk of intraocular haemorrhage, which may be increased in severity if patients are taking anticoagulant medication.

The outcomes of intraocular haemorrhage are poor, with significant deterioration in paracentral and peripheral vision, and subsequent implications for ability to maintain functional independence.

When considering anticoagulation therapy for patients with neovascular AMD, liaison between the general practitioner, cardiologist and ophthalmologist will ensure that an appropriate risk–benefit evaluation is made.

If patients who take anticoagulant medication develop signs of neovascular AMD, it is essential that the ophthalmologist liaise with the GP and/or cardiologist to ensure that the need for anticoagulation, and the target international normalised ratio, are carefully reviewed.

- 1. Klein R, Klein BE, Tomany SC, et al. Ten-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam eye study. Ophthalmology 2002; 109: 1767-1779.

- 2. Ambati J, Ambati BK, Yoo SH, et al. Age-related macular degeneration: etiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic strategies. Surv Ophthalmol 2003; 48: 257-293.

- 3. Ferris FL, Fine SL, Hyman L. Age-related macular degeneration and blindness due to neovascular maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1984; 102: 1640-1642.

- 4. Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Gragoudas ES. Age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol 1988; 32: 375-413.

- 5. El Baba A, Jarrett WH, Harbin TS, et al. Massive hemorrhage complicating age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 1986; 93: 1581-1592.

- 6. Tilanus MA, Vaandrager W, Cuypers MH, et al. Relationship between anticoagulant medication and massive intraocular hemorrhage in age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2000; 238: 482-485.

- 7. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method of estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981; 30: 239-245.

- 8. Sarraf D, Gin T, Yu F, et al. Long-term drusen study. Retina 1999; 19: 513-519.

None identified.