Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) became a notifiable disease in Queensland in 1999. Over the next 5 years, enhanced surveillance of ARF was undertaken in north Queensland, with multiple means used for case identification.1 However, in 2004 the enhanced surveillance had to be discontinued because of competing priorities, and it was replaced by a more routine model of surveillance, relying on health care providers to notify cases spontaneously.

The high percentage of ARF cases documented during the period of enhanced surveillance that were recurrences raised concerns about the effectiveness of the on-going management of Indigenous ARF patients in north Queensland.1 However, in the latter part of 2004, it became apparent that there was another factor contributing to ARF recurrences — the failure of medical practitioners to recognise ARF at an initial presentation.2 Obviously, individuals with unrecognised (“missed”) episodes of ARF do not have the opportunity to receive regular antibiotic prophylaxis, and therefore remain at considerable risk of recurrences of ARF.3 Two examples of missed cases are detailed in the Box 1.

A process for routinely looking for missed cases of ARF was established by Queensland Health at the end of 2004. This required undertaking a detailed “look-back” into the available past medical history of each patient with a notified new case of ARF. It soon became obvious that a considerable number of cases of ARF were being missed in north Queensland, either because: (i) ARF was considered, but either not followed up or the diagnosis was discarded for incorrect reasons (as in the first example in Box 1); or (ii) ARF was not considered at all (as in the second example in Box 1).4

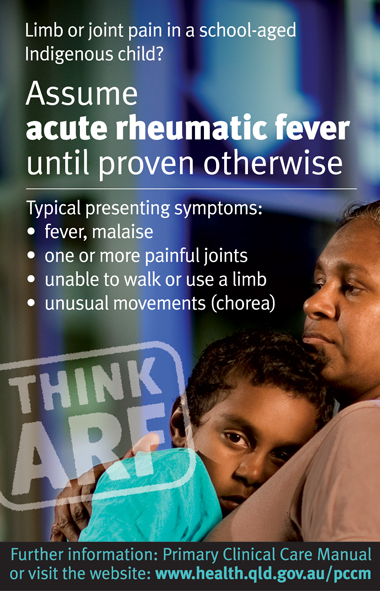

As well as the look-back, more deliberate efforts were made to inform medical practitioners about: the essential features of the disease in north Queensland;1 how to make the diagnosis;3 how each case should be subsequently managed;3 and how ARF was to be notified. These initiatives began in early 2005 (soon after the model of surveillance was changed), and were particularly intensive throughout the next 2 years. They included: hospital grand-round, ward-round and in-service presentations; orientation sessions and tutorials for junior hospital medical staff and medical students; newsletters;2,4,5 and the development and distribution of several supporting resources (an example is shown in Box 2).

school-aged Indigenous children (aged 5–14 years) in north Queensland are at extremely high risk of developing ARF;

ARF usually presents as a rheumatological disorder, with the predominant presenting complaint being either monoarthritis or polyarthritis (which is classically, but not necessarily, migratory in nature);

sudden onset of either refusal to bear weight or non-use of an upper limb (without an obvious cause) is an ominous presenting complaint in an unwell Indigenous child, and ARF must be considered as a very likely cause;

carditis is not a mandatory criterion for the diagnosis of ARF;

unless there is a very specific indication, there is no need for extensive laboratory investigations (such as screening tests for arboviruses, or serum levels of urate, serum complement, antinuclear antibody, and rheumatoid factor) in an Indigenous child in north Queensland who may have ARF, particularly if the child has only had a short illness. These investigations may divert the attention of the requesting practitioner away from ARF to make a spurious diagnosis; and

any concerns should be discussed with a paediatrician or physician familiar with the disease.

Medical practitioners (and rural and remote community health nurses) were requested (including by means of the initiatives detailed above) to use the existing ARF case report form to notify any cases of ARF, even if the cases were initially only suspected. The ARF case definition and the ARF case report form were the same as those used when ARF surveillance began in 1999.1,3

Incidences of ARF during mid 2004 to mid 2009 were calculated using the 2006 Experimental Estimated Resident Populations (ERPs) derived by the Queensland Treasury (Office of Economic and Statistical Research).6 These ERPs are based on 2006 national census data; the Indigenous ERP in north Queensland in 2006 was about 68 400 persons, which is 17% greater than the estimate in the 2006 national census. To enable comparisons to be made, the mid 1999 to mid 2004 average annual incidence rates for ARF1 were recalculated using the 2001 ERPs.

Over the 5 years from mid 2004 to mid 2009, there were 203 notifications of ARF in 194 Indigenous people in north Queensland; this was a 41% increase over the number in the preceding 5 years (Box 3). There was a 23% increase in the average annual incidence compared with that in the preceding 5 years (P > 0.05). There was also a 41% increase in the number of notifications among children aged 5–14 years, with a 29% increase in the annual incidence in this age group (P > 0.05). Increases in notifications were particularly evident in the Torres Strait and Northern Peninsula Area, Cape York, Tablelands and Mt Isa health service districts (data not shown). Indeed, in one health service district (Mt Isa), the recent annual incidence of 95 cases (95% CI, 67–130 cases) per 100 000 Indigenous people was significantly higher than that in the previous 5-year period (40 cases [95% CI, 23–65 cases] per 100 000).

There was a recent 7% increase (P > 0.05) in the number of cases of ARF among females, but otherwise, the proportions of the key features of ARF remained very similar over the two 5-year periods (Box 3).

There were 54 known recurrences of ARF. It could not be determined if one episode of ARF (notified in 2005) was a recurrence or not. Box 4 shows that, of the 54 known recurrences, 34 (63%) occurred between mid 2004 and the end of 2006 and 20 occurred between the beginning of 2007 and mid 2009 (P < 0.01), and that, of the 148 episodes that were not recurrences, 69 (47%) occurred between mid 2004 and the end of 2006 and 79 occurred between the beginning of 2007 and mid 2009 (P > 0.05).

The recent annual incidence of ARF in school-aged Indigenous children in north Queensland (155 episodes per 100 000 Indigenous persons aged 5–14 years) is of particular concern. As “high risk” has been defined by an incidence of over 30 episodes per 100 000 persons aged 5–14 years,3 this incidence indicates that these children are at an extremely high risk of developing ARF. A consequence is that there is a high prevalence of RHD in the region.7,8

The national guidelines on the diagnosis and management of ARF and RHD state: “Many medical practitioners in Australia have never seen a case of ARF, because the disease has largely disappeared from the populations among which they train and work. It is very important that health staff receive appropriate education about ARF before postings to remote areas.”3 Although we agree, in reality there is no mechanism in north Queensland to deliver such an orientation to rural and remote staff in a routine and sustainable way. Fortunately, as part of a national initiative, an RHD Register and Control Program was recently established in Queensland. This program has four coordinators situated throughout north Queensland, whose role is to expand further the initiatives to raise awareness and improve ARF/RHD case management strategies that have been implemented in the region since 2005.

- Jeffrey N Hanna1

- Michele F Clark2

- 1 Cairns Public Health Unit, Tropical Regional Services, Division of the Chief Health Officer, Queensland Health, Cairns, QLD.

- 2 Rheumatic Heart Disease Register and Control Program, Cairns and Hinterland Community and Primary Prevention Services, Queensland Health, Cairns, QLD.

We thank Fiona Tulip for providing the Estimated Resident Populations and Alexandra Raulli for helping with the analyses. Special thanks to Margaret Young for her helpful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

None identified.

- 1. Hanna JN, Heazlewood RJ. The epidemiology of acute rheumatic fever in Indigenous people in north Queensland. Aust N Z J Public Health 2005; 29: 313-317.

- 2. Acute rheumatic fever in north Queensland: mid-2004 to mid-2005. Tropical Public Health Unit Network Communicable Disease Control Newsletter 2005; (51): 1-3.

- 3. National Heart Foundation of Australia (RF/RHD guideline development working group) and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. Diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia — an evidence-based review. Canberra: NHA, 2006. http://www.heartfoundation.org.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/PP-590%20Diagnosis-Management%20ARF-RHD%20Evidence-Based%20Review.pdf (accessed Apr 2010)

- 4. Why are medical practitioners in north Queensland missing cases of acute rheumatic fever? Tropical Population Health Unit Network Communicable Disease Control Newsletter 2007; (55): 1-4.

- 5. Three more missed cases of acute rheumatic fever. Tropical Population Health Unit NetworkCommunicable Disease Control Newsletter 2008; (57): 1-2.

- 6. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Demographic Statistics September quarter 2009. Canberra: ABS, 2010. (ABS Cat. No. 3101.0.) http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/26D01CDE59A47371CA2576F0001 C7F50/$File/31010_sep%202009.pdf (accessed Apr 2010).

- 7. Rothstein J, Heazlewood R, Fraser M. Health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in remote Far North Queensland: findings of the Paediatric Outreach Service. Med J Aust 2007; 186: 519-521. <MJA full text>

- 8. McLean A, Waters M, Spencer E, Hadfield C. Experience with cardiac valve operations in Cape York Peninsula and the Torres Strait Islands, Australia. Med J Aust 2007; 186: 560-563. <MJA full text>

Abstract

Objectives: To ascertain whether changing from enhanced to routine surveillance had any deleterious impact on notification rates of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) among Indigenous people in north Queensland; and to determine whether initiatives to raise awareness about ARF among medical practitioners during the routine surveillance period were associated with any changes in the numbers of recurrences of the disease among Indigenous people in the region.

Design, participants and setting: Routine surveillance of all cases of ARF, and (to identify unrecognised prior episodes) retrospective checking of the medical records of Indigenous people with notified first cases of ARF from mid 2004 to mid 2009 in north Queensland, which has an estimated resident Indigenous population of about 68 400.

Main outcome measures: Rate of notifications of ARF during the routine surveillance period (mid 2004 to mid 2009) compared with that in the previous 5 years of enhanced surveillance; proportion of recurrent episodes of ARF that occurred from mid 2004 to the end of 2006 compared with the proportion in the following 2.5 years.

Results: There were 203 notifications of ARF in 194 Indigenous people in north Queensland from mid 2004 to mid 2009, and this was a 23% increase in the average annual incidence compared with that in the preceding 5 years. Of the 54 recurrences, 34 (63%) occurred between mid 2004 and the end of 2006 and 20 occurred between the beginning of 2007 and mid 2009 (P < 0.01). Of the 148 episodes that were not recurrences, 69 (47%) occurred in the first 2.5 years and 79 in the more recent 2.5 years (P > 0.05).

Conclusions: Changing from enhanced to routine surveillance in 2004 did not have a negative impact on notifications of ARF. The initiatives to raise awareness about ARF probably contributed to fewer missed cases and therefore to the considerable increase in the number of notifications, and ultimately to fewer recurrences.