The known: First Nations peoples in Australia face persistent inequities in surgical care, with limited region‐specific research to guide culturally safe perioperative care.

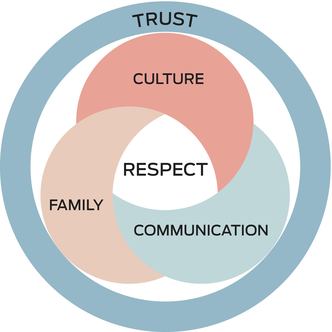

The new: This research in the Northern Territory highlights that respect is a core principle for First Nations people in the perioperative journey, with family, culture, and communication key values that, when upheld, foster trust.

The implications: Embedding these values into perioperative care may improve patient journeys and health outcomes. This research provides a foundation to enable the co‐design of culturally safe, patient‐centred perioperative care models.

Globally, First Nations communities have advocated for accessible health services, community participation and governance, continuous quality improvement, a culturally appropriate and clinically skilled workforce, flexible care, and holistic health care from surgical services.1 In Australia, the disparity in access to surgical care and perioperative experiences for First Nations people is well documented and remains a critical issue in addressing health equity.2 Despite the global recognition that surgical conditions account for one‐third of the overall disease burden,3 First Nations Australians are less likely to undergo a medical or surgical procedure in hospital compared with non‐First Nations Australians.4 First Nations Australians have twofold higher rates of emergency admissions involving surgery compared with non‐First Nations Australians.5 However, this does not compensate for lower rates of elective (planned) surgery, and First Nations Australians still experience longer waiting times for admission for elective surgery lists than non‐First Nations people.6

In the Northern Territory, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make up 26% of the population7 and represent more than 100 distinct Nations with diverse languages and cultures.8 For First Nations peoples, particularly those who live in remote communities in the NT, colonisation and racism are associated with systemic inequities and a disproportionate burden of chronic illness, resulting in a significant reduction in life expectancy.9 Consumer‐driven research in the NT has specifically drawn attention to inequities for people with chronic conditions like kidney disease,10 rheumatic heart disease11 and liver disease,12 and pathways to address inequities through enhanced communication, access to interpreters and clinician training to improve cultural safety.13,14,15 While there is considerable research into First Nations values for health and wellbeing, there is a lack of region‐specific and culturally informed research addressing local priorities and values in perioperative care.

This article focuses on the research question “What do Aboriginal people in the NT value during the operation journey?” To co‐design culturally safe perioperative models of care, it is imperative to have a strong understanding of what First Nations people value when contemplating, undergoing and recovering from surgery. As clinicians and patients will have different priorities,16 listening and reflection are central to generating shared understanding. This article is a starting point in this process — listening and reflecting with First Nations co‐researchers and consumers to contribute to an evidence base around their values for health and wellbeing, specifically in the surgical context. The findings of this research will also serve as a foundation for developing culturally appropriate models of perioperative care, which are needed to address systemic inequities for First Nations Australians.

Methods

To understand barriers to and enablers of equitable and culturally safe care in the NT,17 this article centres on listening to what First Nations people value during the operation journey and reflecting on their perspectives and lived experiences. This article builds on extensive research on Aboriginal ways of being, knowing and doing18 and uses participatory action research as a methodological approach to recognise and destabilise power imbalances between clinicians and Aboriginal patients. Aboriginal participatory action research fosters community ownership over research outcomes by positioning Aboriginal people as experts in their own lives and actively engaging them in shaping health care experiences, thereby unsettling dominant power relationships.19 Engaging with the community‐based participatory action research framework, this article focuses on the “Look and Listen” and “Think and Reflect” stages to provide a basis for further research to collaborate and co‐design models of care (Box 1).20

Within this approach, data collection methods like yarning, deep listening and reflection are used to foreground First Nations worldviews and knowledge‐sharing practices. Sharmil and colleagues20 demonstrate how Western methods (participatory action research) can be used in conjunction with the Indigenous methods of yarning (consulting), Dadirri (deep listening, from the Ngangikurungkurr [River People] from Daly River) and Ganma (two‐way knowledge sharing, from the Yolngu people from Arnhem Land), specifically in health research. In contrast to structured interviews, yarning allows for culturally appropriate and open‐ended dialogue, facilitating richer, more inclusive discussions that respect the autonomy and lived experiences of patients. As Bessarb21 describes, yarning involves participants and researchers sharing stories to build relationships; yarns unfold as a conversation that fosters reciprocity, trust and respect, rather than extracting knowledge through questions and answers. Listening is an important method to use alongside yarning. The work of Ungunmerr‐Baumann and colleagues22 details how Dadirri has been co‐developed in the NT as “a deep contemplative process of listening to one another” that combines Indigenist and Western epistemologies through reflective practice and truth telling.

For this study, participants were recruited from ongoing relational research with a group of Aboriginal kidney health mentors23 and established connections with a cohort of transplant recipients and people receiving dialysis in the NT. This group has lived experience of the operation journey, including with fistulas for dialysis as well as kidney transplantation, and is therefore well placed to reflect on surgical care. This project used purposive and snowball sampling, where First Nations consumers with known experiences of surgery were invited to participate in yarning circles. Sampling aimed to ensure that a range of perspectives was engaged to reflect diversity in gender, age, region and kinship connections. We use the term “gender” to refer to participants’ self‐identified social and cultural roles. Gender representation was evident among participants, but the Aboriginal kidney health mentors who are the senior co‐authors in this study are all male. Discussions covered the scope of the operation journey, from contemplation of surgery to recovery, with patients sharing their experiences and the clinician–researcher (EBW) providing insights about health care processes. Participants were remunerated with vouchers for their time and co‐researchers NW, PH, DC, JR were paid through established salaried roles at Purple House with support from Menzies School of Health Research.23

Yarning circles provided a space for shared storytelling, listening, continuous reflection and relationship building, and took place in non‐clinical settings at times convenient for participants. Circles were co‐facilitated by non‐Indigenous researchers EBW and SP and Aboriginal kidney health mentors NW, PH, DC and JR. The sessions aimed to foster trust, reciprocity, and shared understanding of the operation journey. Yarning circles were audio recorded and then transcribed, and notes were taken by the researchers during the sessions. The listening method enabled EBW and SP to practise reflexivity around their positionality as white settlers and power dynamics as clinicians and academics.

Iterative data analysis, interpretation and reflection took place collaboratively with the Aboriginal co‐researchers. These subsequent reflective cycles of sharing stories, listening deeply and understanding together were intended to generate nuanced and grounded insights into the priorities of First Nations people as they navigate surgery. After coding transcripts and notes to identify emerging themes, these themes were presented back to the Aboriginal co‐researchers for further reflection and validation. Additional yarning circles with all researchers focused on visually representing discussions around the peri‐operative journey and First Nations peoples’ values in this process.

The Human Research Ethics Committee of Northern Territory Health and Menzies School of Health Research, advised by the Aboriginal Ethics Sub‐Committee, approved the study (2022‐4467). This article adheres to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Supporting Information, section 1).24 In addition, we conducted this study in accordance with the Centre of Research Excellence in Aboriginal Chronic Disease Knowledge Translation and Exchange (CREATE) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander quality appraisal tool (Supporting Information, section 2)25 and aligned our approach with the Consolidated Criteria for Strengthening the Reporting of Health Research Involving Indigenous Peoples (CONSIDER) statement (Supporting Information, section 3)26 to ensure rigour in First Nations research ethics and governance.

This project was instigated by the Top End Indigenous Research Group of the INFERR (INtravenous iron polymaltose for First Nations Australian patients with high FERRitin levels on hemodialysis) study27 and was co‐led and guided by Aboriginal investigators who shared governance over design, conduct and interpretation. Community priorities shaped the research focus, and local protocols — including cultural safety processes, informed consent and data stewardship — were followed throughout. Intellectual and cultural property was respected through clear protocols: First Nations knowledge remains the property of participants, and all data were de‐identified and used only with guidance from Aboriginal research advisors on what could be appropriately shared. The study was guided by a First Nations research paradigm and grounded in strengths‐based approaches that acknowledged resilience and self‐determination. Findings are being used to inform culturally safe perioperative models of care, and dissemination strategies aim to support sustainable policy and practice change across local, regional and national settings. Capacity strengthening was built into the process through mentoring, reciprocal learning and consumer engagement at every stage.

Terminology

We respectfully use the terms “First Nations peoples” and “communities”, also referred to as Indigenous peoples by the United Nations, for those who have ancestral connections, cultural roots and communal links to the societies that existed in the land before colonisation. In Australia, this refers to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In the NT, the First Nations co‐researchers and participants for this study identify as Aboriginal and express a preference for using this term to refer to themselves.

Positionality of author team

The research team brings diverse positionalities and lived experience to this work. Senior Aboriginal co‐authors (Neil Wilkshire, Peter Henwood, David Croker and Jampijinpa Ross) are Aboriginal kidney health mentors and leading members of the Renal Advocacy Advisory Committee in the Top End, with personal experience of kidney disease, surgery (including fistulas and transplantation) and systemic health inequities. Mark Mayo, a Mudburra and Torres Strait Islander researcher, brings over three decades of experience in biomedical research and leadership in First Nations health and workforce development. The broader team includes male and female white settler clinicians (Edith Waugh, Matthew Hare and David Story) and qualitative researchers (Sophie Pascoe and Marita Hefler) committed to equity‐focused First Nations health research. These varied standpoints shaped the study's design, interpretation and ethical grounding.

Results

Data collection occurred iteratively between May 2023 and September 2024 in Garramilla (Darwin). Eighteen participants, including four First Nations co‐researchers (NW, PH, DC, JR), participated in two focused yarning circles: group 1 (C1) and group 2 (C2). Two First Nations consumer engagement officers helped to coordinate the sessions, and two white settler researchers (EBW, SP) facilitated the sessions. The Aboriginal participants had kinship connections spreading across the NT and interstate, from Saltwater Country to Desert Country. They included a range of age and language groups, and balanced gender representation. The participants all had shared experiences of chronic kidney disease and surgery associated with dialysis, among other individual surgeries. While all participants had connections to remote communities, most had relocated to urban centres for dialysis. The yarning circles were held in flexible, culturally safe, non‐health care environments, allowing participants to come and go, choose their level of engagement, or remain silent as they wished, aligning with Indigenist approaches. Senior co‐authors (NW, PH, DC, JR) led subsequent reflection and interpretation.

Yarning covered both the practical and tangible things that people want in their perioperative journeys, as well as the underlying ethics and principles for care (Box 2). The multidimensionality of the term “values” — as a noun “the beliefs people have, especially about what is right and wrong and what is most important in life, that control their behaviour” as well as a verb “to consider something as important” — was highlighted in the yarning, listening and reflecting processes.

Things that are valued

Family

The yarning circles emphasised the important role of family throughout a patient's surgical journey, which is considered essential for a positive operation experience, representing a more collective approach to health and wellbeing compared with individual‐centred models of care. Participants explained that family involvement is key to shared decision‐making processes, particularly when discussing operations as treatment options. One participant emphasised that it is “not just about individual … family has responsibility [in the process] … check that everybody is on track about that operation” (C2). Family members play a crucial role in transmitting information and participating in the decision‐making process, including consent for surgery and anaesthesia, often guided by kinship connections and protocols. These protocols may evolve based on clinical conditions and circumstances, and support people and decision makers might change when health care interventions or outcomes escalate. Co‐researchers explained that complex family dynamics and obligations may be at play in terms of identifying an appropriate person “who has authority to give permission or to spiritually support the patient” (C2).

The value placed on family responsibilities also presents a tension between caring for patients undergoing surgery and broader family obligations: “Mob understand that sickness needs operations … yeah we do want to stay [in hospital] … but … we have sick elderly back on Country and other [ceremony or funeral time] obligations” (C1). Co‐researchers explained that family responsibilities often take precedence over their own health, and there can be spiritual and wellbeing implications of failing to meet these obligations.

Participants emphasised the value of having a support person embedded throughout the operation journey, from initial appointments to the actual surgery and postoperative care, to look after and advocate for the patient. “We have to talk first and make sure that my family understands … that gives you the time and your family [the] time to talk about it and make that decision what's best … it's a cultural thing before we make that next step” (C2). This quote highlights the importance of family discussions in reaching a collective decision. Another participant explained how this need for connection persists throughout the surgical experience: “Before they go in … they need someone they can recognise … they have that connection … focus on them” (C2). The presence of a support person and family members during the inpatient phase is crucial for patient comfort and trust. One participant shared: “So when they come out of that operation, explain it to the family. Or the carer … who is going to bring back and tell the family. He's going to be more questioned. Carer has responsibility … if things go wrong … they need to tell the family … if you want to have that trust … that patient trust … that family trust” (C2).

Culture

Incorporating culture into operation journeys is fundamental for Aboriginal people's positive healing and wellbeing experience in hospital. Participants emphasised the importance of upholding cultural practices and protocols — including traditional medicine, smoking and muttering/singing — alongside biomedical treatments. Respecting cultural roles and positionalities is also important. One participant shared that “Message is more effective if [comes] from people they recognise and the Elders … people from their community … … they will hear Elders more” (C2). This indicates the significant role of Elders in offering guidance and support rooted in traditional wisdom and cultural knowledge.

Participants stressed the need to develop perioperative care plans that explicitly account for cultural practices, including incorporation of traditional foods, traditional medicines, and healing practices specific to the local context (eg, participants mentioned Ngangkari healing in Central Australia). A crucial aspect of holistic healing, according to participants, is maintaining connections to Country, which provides spiritual nourishment and a sense of belonging. As one participant shared, “To make people's health better they have to feel comfortable … nobody said they can have a family member or they can get some of their own bushtucker brought in … [this] makes connection with Country and makes healing” (C2). This statement underscores the importance of integrating cultural elements to create a healing environment both before and after surgery. The reintegration of individuals into their communities following an operation is considered crucial for holistic healing.

Communication

Clear communication was central to ensuring that there is shared understanding between clinicians and Aboriginal patients around operative procedures, treatment options, processes and timelines, which are all needed for informed decision making. Participants stressed the need for explanations to be framed in culturally comprehensible terms: “We need to turn around and tell them [about] the right way for that process so they can understand that code. So when they talk to another Aboriginal person that can explain it in a way … explain the right way to [the] patient and family why they need the operation” (C2). This reflects the need for clear, respectful explanations that bridge cultural differences in understanding medical procedures.

Despite emphasising the importance of culturally safe communication, participants described their previous surgical experiences and other encounters with mainstream health systems where this was lacking. The absence of interpreter services and culturally appropriate bidirectional knowledge exchange contributes to fear and disengagement in the operation journey. Confrontational statements like “You need to have the surgery or you’re going to finish up [die]” only instil fear, with one participant sharing “They shouldn’t go around telling [that], you’re just really scaring them … I’d rather go home and die [than stay and have surgery]” (C1).

For Aboriginal patients from remote areas, the lack of consistent follow‐up after surgery is especially problematic because of limited health service capacity and restricted seasonal access: “During the wet season, I had to swim across croc‐infested waters to collect tablets from the clinic” (C1). After surgery, people usually want to return to their communities as quickly as possible, but their recovery may be impacted by limited telecommunication networks and irregular health care services. “Patient and family should be informed after the operation about findings. Nobody told me what to do, no follow‐up” (C2). Participants suggested that better informed family and community health centres could address this gap in the perioperative process and ensure ongoing care.

Inconsistent messaging from health care providers further contributes to confusion: “One doctor says this, and the next one says something different — lots of conflicting information” (C2). Such inconsistencies erode trust in the medical system, which is already fragile for many Aboriginal patients.

Participants also recommended having a support person accompany the patient throughout the perioperative journey, which can foster better communication between clinicians, patients and their families. The practice enhances understanding and helps address concerns in real time, ensuring that patients feel more supported during stressful periods. Establishing trust through open, honest and culturally sensitive communication is fundamental. Adhering to cultural norms, such as asking permission to discuss sensitive topics and using appropriate language, was seen as demonstrating cultural competence and respect. However, participants noted that these practices are not routinely followed, even though they are key to ensuring that Aboriginal patients feel understood and supported throughout their perioperative journey.

Ethics of care in the operation journey

Cultural respect

Participants described experiences of being dismissed and not heard by health care professionals, which they linked to respect. They suggested connecting with patients, including by asking where they are from and using ice breakers, and refraining from making assumptions about their lives and beliefs. Participants articulated the hurt and disrespect they can feel in interactions with the health system: “I get really upset … because [doctors] think Aboriginal people are dumb, but they’re not, they know what they’re doing and saying … they [doctors] need to listen” (C2). In addition, adhering to cultural protocols — including those relating to gender norms dictating specific gender roles in health care environments, traditional kinship rules restricting interactions within families, and specific rituals surrounding bodily fluids — is critical in this context. For example, if a family member has passed away in hospital, there may be restrictions for their relatives going to the room or ward where they passed. This underscores the critical need for health care providers to actively listen and respect patients’ knowledge and experiences.

Linked to the previous theme of culture, participants highlighted the need to respect cultural practices. One participant recounted an incident where traditional food was disregarded by a health care professional: “I brought her [a relative having surgery] in a kangaroo tail, turtle and all the yam … they got it, and they threw it in the bin. The nurse said ‘it is not lunch’. And that was not for them [to say]” (C1). This example demonstrates a lack of cultural sensitivity and respect for traditional practices, which can significantly impact patient care and trust in the health care system.

The theme of respect extends to issues of patient autonomy and representation. One participant noted: “Once you’re inside the hospital as a patient … if there was a problem, the first people they contact are Aboriginal liaison officers … called by doctors and not the patient … power is with doctors … should be with the patient” (C1). Part of respect is empowering patients to ensure they are listened to when discussing their care.

Systemic barriers can also impede respectful care. A co‐researcher expressed frustration with institutional limitations in their work as an Aboriginal kidney health mentor:23 “I am stopped at the door ‘but we haven’t got no clout in the hospital system’ … I hand over patient to [the] Aboriginal liaison officer … at the moment, that is all we can do … I would like to take patients and walk them through the whole system and journey” (co‐researcher comments/reflections). This indicates a desire for more options for culturally appropriate support throughout the patient journey.

Trust

As the ethics of respect and the priorities of culture, family and communication coalesce, trust is generated. Participants emphasised the importance of trust in facilitating the operation journeys of Aboriginal patients in the NT. Cultural respect is fundamental to building trust, as it involves integrating cultural values, practices and protocols into care. Clear, honest and respectful communication is essential in fostering trust between health care providers and patients. This is especially important when addressing fears and misconceptions about medical procedures; as one participant described, “Aboriginal people frightened to come to hospital … I don’t want them to open me … more information about how big the cut will be … I’d rather die than be cut open … will it heal up?” (C2).

To address these concerns and build trust, the participants discussed that health care professionals must engage in two‐way communication with patients and their communities: “They got all the information from us … with communication everything works better … doctors need to talk to us first” (co‐researcher comments/reflections). This approach not only respects cultural protocols but also ensures that information is disseminated effectively within the community. Furthermore, involving families and community leaders, and organising local meetings and awareness sessions, can help demystify medical procedures and alleviate fears, leading to “better outcome[s] for Aboriginal people going through the hospital system … [to] not [be] afraid … from babies to old people” (C2). By addressing emotional needs and providing comprehensive information, health care providers can help patients navigate the “emotional rollercoaster” (C1) of hospitalisation and build the trust that is necessary for effective care.

Discussion

In asking and listening to “What is valued by Aboriginal people in the NT in their operation journeys?”, this research underscores the need for culturally safe perioperative care. While similar themes have emerged from previous studies conducted in the Top End of the NT,13,14 such as the significance of cultural safety and holistic health, this study provides specific insights into the perioperative context. Although not the focus of the research question, a major finding of this research is the identification of persistent deficiencies in cultural safety, communication and respect across surgical journeys, undermining trust at various stages. These findings are especially significant considering recent updates to the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law, administered by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency, which now allow patients to make a notification against a registered health practitioner for culturally unsafe care, recognising such conduct as a breach of professional standards.28 As Aboriginal people view health and wellbeing holistically, encompassing biopsychosocial, spiritual and cultural dimensions,29 our study reaffirms the principles of culturally appropriate care. However, our results highlight the need for perioperative processes to align with First Nations worldviews by incorporating family involvement, traditional healing practices and recognition of connection to Country during consultations, decision making and postoperative recovery. Health care systems should enable culturally appropriate communication to facilitate options for collective decision making and enhance continuity of perioperative care by fostering strong, culturally competent relationships between multiple health care stakeholders (primary health care providers, surgical teams, anaesthetists, physicians, allied health practitioners, nursing staff) and patients with their supportive community representatives. Trust — the overarching desired outcome — should cultivate culturally appropriate, patient‐centred care throughout the operation journey.

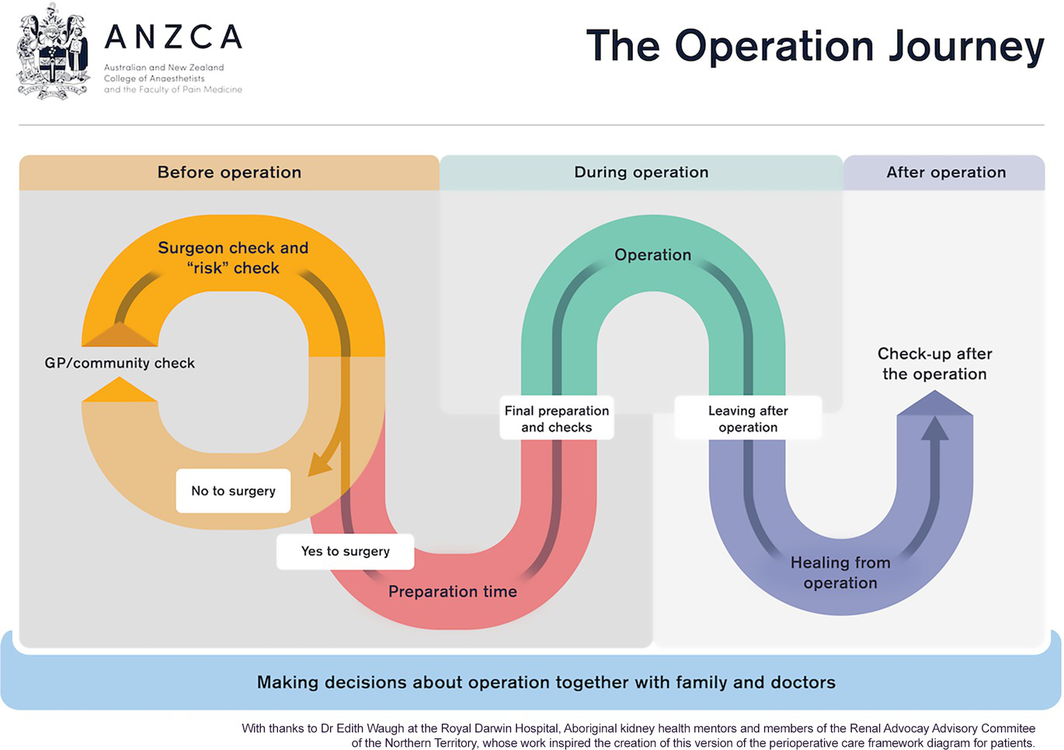

Effective communication in perioperative care of Aboriginal people requires respectful, culturally competent, iterative and bidirectional dialogue, which should be embedded within a patient‐centred multidisciplinary perioperative care framework30 (Box 3). Respecting cultural beliefs, cultural practices and community autonomy in health care decisions, including informed consent, especially where communities were historically disempowered, is critical to empowering Aboriginal patients in the perioperative journey. Findings from previous research suggest that Aboriginal patients face significant communication barriers in health care settings.31 Integrating interpreters and cultural liaisons has been shown to enhance understanding of and adherence to treatment plans.32,33,34 Cultural safety training for health care staff can further improve communication with patients and patient experiences.35 Building on this body of evidence, our study highlights the importance of consistent, high quality perioperative communication and the role of long term trust‐based relationships with health care providers, particularly during stressful perioperative periods.

For Aboriginal people navigating surgery, connecting to Country is not just a preference, but a fundamental aspect of health, providing spiritual nourishment, cultural continuity and a sense of belonging.36 Our study indicates that integrating cultural knowledge and practices can improve medical understanding and communication between Aboriginal patients and perioperative health care providers, ultimately leading to better health outcomes.

To incorporate Aboriginal people's values and ethics of care, health care systems must adapt to mitigate barriers and provide accessible, respectful and culturally aligned services. Racism, both overt and systemic, significantly impacts Aboriginal people's engagement with health care,37,38 including perioperative services. Creating antiracist perioperative health care environments through provider education, policy reforms and institutional accountability is essential to foster trust and improve health outcomes for Aboriginal patients.

Strengths and limitations

Our study's strengths include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership, strong First Nations representation and adherence to local cultural protocols, ensuring the research was grounded in community priorities and guided by an Indigenous paradigm. The qualitative design enabled in‐depth exploration of what Aboriginal people in the NT value in their perioperative journey. Diverse participation across languages, regions and care experiences further strengthened the data collection and analysis. However, as participants were recruited based on their shared lived experiences of chronic kidney disease, fistula surgery and dialysis, there is a risk of selection bias toward those more engaged with care.

While there are synergies with existing research around culturally safe care,10,11,13,32 our findings are context specific and localised; they are not intended to generate generalisable themes that may not reflect the experiences of other First Nations peoples in different settings. Our study once again foregrounds the importance of culturally safe care, specifically for perioperative care, and acknowledges the long history of First Nations research and advocacy in this space.39,40,41

Conclusion

By listening to “what Aboriginal people value during the operation journey”, our study provides an in‐depth view of patient values, highlighting culturally specific needs and priorities often overlooked in Western health care systems. The findings emphasise that respect for family involvement, cultural practices, culturally competent communication and connection to Country are central to the perioperative journey. Respect fosters the trust essential for creating a culturally safe and supportive environment that enables shared decision making and improves the perioperative care experience. Health care systems should integrate these values, fostering environments where Aboriginal patients feel respected and supported throughout their surgical experiences. This research, driven by community insights, lays the foundation for developing culturally appropriate perioperative health care models aligned with national health priorities; in doing so, it contributes to closing the health care gap for Aboriginal Australians. Future research is needed to validate these findings across different communities, explore broader health care policy implications, and assess whether Westernised hospital systems can adapt to meet the needs of an increasingly diverse Australian population, including First Nations peoples, refugees and immigrants.

Box 1 – Engaging with the community‐based participatory action research framework: focusing on the “Look and Listen” and “Think and Reflect” stages*

* Adapted from Sharmil et al.20

Box 3 – Consumer version of the perioperative care framework developed by the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) in discussions with the Renal Advocacy Advisory Committee* in the Northern Territory30

GP = general practitioner. * The Renal Advocacy Advisory Committee includes co‐authors of this article.

Received 21 December 2024, accepted 7 May 2025

- Edith B Waugh1,2,3

- Marita Hefler1,4

- Sophie Pascoe1

- Mark Mayo1

- Matthew JL Hare1,2

- David A Story3,5

- Neil Wilkshire6

- Peter Henwood6

- David Croker6

- Jampijinpa Ross6

- 1 Menzies School of Health Research, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT

- 2 Royal Darwin Hospital, Tiwi, NT

- 3 University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

- 4 Flinders University, Darwin, NT

- 5 Austin Health, Melbourne, VIC

- 6 Purple House, Alice Springs, NT

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Charles Darwin University, as part of the Wiley – Charles Darwin University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Data Sharing:

Data collected and analysed during the study are not publicly available due to privacy issues and ethical considerations. Data may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this article captures the knowledge and lived experiences of Indigenous people who have passed. With permission from family, we refer to our senior co‐author as “Jampijinpa” Ross. This article is a testament to his contributions to First Nations health. Out of cultural sensitivity, we do not use the names nor images of Indigenous people who participated in this research who have subsequently passed away.

Edith Waugh received an ANZCA Foundation (Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists) Health Equity Grant 2022. The funding allowed planning, coordination and completion of focus (yarning) groups; participation and sharing of First Nations knowledge was appropriately reimbursed. Edith Waugh is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Scholarship. Matthew Hare is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (grant number 1194698), the Sylvia and Charles Viertel Foundation and an Australian Diabetes Society Skip Martin Fellowship.

The Top End Indigenous Reference Group and research assistant Stephanie Long from the INFERR (INtravenous iron polymaltose for First Nations Australian patients with high FERRitin levels on hemodialysis) study at Menzies School of Health Research were the catalysts leading to this study. This study emerged in response to their feedback about exploring postoperative outcomes for First Nations people in the Northern Territory and the need for this research to incorporate patient values.

No relevant disclosures.

Author contributions:

Waugh EB: Conceptualization; methodology; investigation (data collection); formal analysis; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing; project administration; funding acquisition. Hefler M: Methodology; formal analysis; writing – review and editing; supervision. Pascoe S: Methodology; investigation (data collection); formal analysis; writing – review and editing; project administration. Mayo M: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing; supervision. Hare MJL: Writing – review and editing; supervision. Story DA: Writing – review and editing; funding acquisition, supervision. Wilkshire N: Writing – methodology; investigation (data collection); formal analysis; review and editing; supervision. Henwood P: Writing – methodology; investigation (data collection); formal analysis; review and editing; supervision. Croker D: Writing – methodology; investigation (data collection); formal analysis; review and editing; supervision. Ross J: Writing – methodology; investigation (data collection); formal analysis; review and editing; supervision.

- 1. Koea J, Ronald M. What do Indigenous communities want from their surgeons and surgical services: a systematic review. Surgery 2020; 167: 661‐667.

- 2. O’Brien P, Bunzli S, Lin I, et al. Addressing surgical inequity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia's universal health care system: a call to action. ANZ J Surg 2021; 91: 238‐244.

- 3. Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L, et al. Global surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015; 386: 569‐624.

- 4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Module 3: Access to health care services. In: Cultural safety in health care for Indigenous Australians: monitoring framework. Canberra: AIHW, 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous‐australians/cultural‐safety‐health‐care‐framework/contents/module‐3‐access‐to‐health‐care‐services (viewed Sept 2024).

- 5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian hospital statistics 2012–13 [Cat. No. HSE 145]. Canberra: AIHW, 2014. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/hospitals/australian‐hospital‐statistics‐2012‐13/summary (viewed May 2025).

- 6. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, National Indigenous Australians Agency. 3.14: Access to services compared with need. In: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework. Canberra: AIHW, National Indigenous Australians Agency, 2023. https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/3‐14‐access‐to‐services‐compared‐with‐need (viewed Sept 2024).

- 7. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Northern Territory: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population summary. Canberra: ABS, 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/northern‐territory‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐population‐summary (viewed Sept 2024).

- 8. Northern Territory Government. Aboriginal languages in NT. Darwin: Northern Territory Government, 2022. https://nt.gov.au/community/interpreting‐and‐translating‐services/aboriginal‐interpreter‐service/aboriginal‐languages‐in‐nt (viewed Sept 2024).

- 9. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health and wellbeing of First Nations people. Canberra: AIHW, 2024. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias‐health/indigenous‐health‐and‐wellbeing (viewed Sept 2024).

- 10. Hughes J, Freeman N, Beaton B, et al. My experiences with kidney care: a qualitative study of adults in the Northern Territory of Australia living with chronic kidney disease, dialysis and transplantation. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0225722.

- 11. Wade V, Stewart M. Bridging the gap between science and Indigenous cosmologies: rheumatic heart disease Champions4Change. Microbiol Aust 2022; 43: 89‐92.

- 12. Binks P, Ross C, Gurruwiwi GG, et al. Adapting and translating the ‘Hep B Story’ app the right way: a transferable toolkit to develop health resources with, and for, Aboriginal people. Health Promot J Austr 2024; 35: 1244‐1254.

- 13. Kerrigan V, McGrath SY, Majoni SW, et al. “The talking bit of medicine, that's the most important bit”: doctors and Aboriginal interpreters collaborate to transform culturally competent hospital care. Int J Equity Health 2021; 20: 170.

- 14. Kerrigan V, Lewis N, Cass A, et al. “How can I do more?”: cultural awareness training for hospital‐based healthcare providers working with high Aboriginal caseload. BMC Med Educ 2020; 20: 173.

- 15. Kerrigan V, McGrath SY, Baker RD, et al. “If they help us, we can help them”: First Nations peoples identify intercultural health communication problems and solutions in hospital in Northern Australia. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2024; https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615‐024‐02160‐4 [Epub ahead of print].

- 16. Artuso S, Cargo M, Brown A, Daniel M. Factors influencing health care utilisation among Aboriginal cardiac patients in Central Australia: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13: 83.

- 17. Waugh E, Mayo M, Hefler M. Grant focuses on First Nations people. ANZCA Bull 2022; 31: 42‐44.

- 18. Martin K. Ways of knowing, being and doing: a theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous and Indigenist research. J Aust Stud 2003; 27: 203‐214.

- 19. Dudgeon P, Bray A, Darlaston‐Jones D, Walker R. Aboriginal participatory action research: an Indigenous research methodology strengthening decolonisation and social and emotional wellbeing [discussion paper and literature review]. Melbourne: Lowitja Institute, 2020. https://www.lowitja.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/05/LI_Discussion_Paper_P‐Dudgeon_FINAL3.pdf (viewed Apr 2025).

- 20. Sharmil H, Kelly J, Bowden M, et al. Participatory action research–Dadirri–Ganma, using yarning: methodology co‐design with Aboriginal community members. Int J Equity Health 2021; 20: 160.

- 21. Bessarab D, Ng’andu B. Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. Int J Crit Indig Stud 2010; 3: 37‐50.

- 22. Ungunmerr‐Baumann MR, Groom RA, Schuberg EL, et al. Dadirri: an Indigenous place‐based research methodology. AlterNative 2022; 18: 94‐103.

- 23. Pascoe S, Croker C, Ross L, et al. The role of Aboriginal kidney health mentors in the transplant journey: a qualitative evaluation. Health Promot J Austr 2025; 36: e70000.

- 24. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349‐357.

- 25. Harfield S, Pearson O, Morey K, et al. Assessing the quality of health research from an Indigenous perspective: the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander quality appraisal tool. BMC Med Res Methodol 2020; 20: 79.

- 26. Huria T, Palmer SC, Pitama S, et al. Consolidated criteria for strengthening the reporting of health research involving Indigenous peoples: the CONSIDER statement. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019; 19: 173.

- 27. Long S, Ross C, Koops J, et al. Engagement and partnership with consumers and communities in the co‐design and conduct of research: lessons from the INtravenous iron polymaltose for First Nations Australian patients with high FERRitin levels on haemodialysis (INFERR) clinical trial. Res Involv Engagem 2024; 10: 73.

- 28. Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. National Law amendments. Melbourne: AHPRA, 2024. https://www.ahpra.gov.au/About‐Ahpra/Ministerial‐Directives‐and‐Communiques/National‐Law‐amendments (viewed Apr 2025).

- 29. Garvey G, Anderson K, Gall A, et al. The fabric of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander wellbeing: a conceptual model. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 7745.

- 30. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. A framework for perioperative care in Australia and New Zealand. Melbourne: ANZCA, 2021. https://www.anzca.edu.au/getContentAsset/6959c2b4‐64dc‐4e7f‐8341‐8f74b72f1a14/80feb437‐d24d‐46b8‐a858‐4a2a28b9b970/The‐Perioperative‐Care‐Framework‐document.pdf (viewed May 2025).

- 31. Amery R. Recognising the communication gap in Indigenous health care. Med J Aust 2017; 207: 13‐15. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2017/207/1/recognising‐communication‐gap‐indigenous‐health‐care

- 32. Ralph AP, Lowell A, Murphy J, et al. Low uptake of Aboriginal interpreters in healthcare: exploration of current use in Australia's Northern Territory. BMC Health Serv Res 2017; 17: 733.

- 33. Kerrigan V, McGrath SY, Majoni SW, et al. From “stuck” to satisfied: Aboriginal people's experience of culturally safe care with interpreters in a Northern Territory hospital. BMC Health Serv Res 2021; 21: 548.

- 34. Lawrence M, Dodd Z, Mohor S, et al. Improving the patient journey: achieving positive outcomes for remote Aboriginal cardiac patients. Darwin: Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, 2009. https://www.lowitja.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/05/Improving_the_patient_journey.pdf (viewed Apr 2025).

- 35. Jongen C, McCalman J, Bainbridge R, Clifford A. Health workforce development interventions to improve cultural competence. In: Cultural competence in health: a review of the evidence. Singapore: Springer, 2017; pp. 49‐64.

- 36. Kingsley J, Townsend M, Henderson‐Wilson C, Bolam B. Developing an exploratory framework linking Australian Aboriginal peoples’ connection to Country and concepts of wellbeing. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013; 10: 678‐698.

- 37. Kairuz CA, Casanelia LM, Bennett‐Brook K, et al. Impact of racism and discrimination on physical and mental health among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living in Australia: a systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health 2021; 21: 1302.

- 38. Gatwiri K, Rotumah D, Rix E. BlackLivesMatter in healthcare: racism and implications for health inequity among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 4399.

- 39. Taylor K, Guerin P. Health care and Indigenous Australians: cultural safety in practice. 2nd ed. Melbourne: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

- 40. Durey A, Thompson SC. Reducing the health disparities of Indigenous Australians: time to change focus. BMC Health Serv Res 2012; 12: 151.

- 41. Bond CJ, Singh D. More than a refresh required for closing the gap of Indigenous health inequality. Med J Aust 2020; 212: 198‐199.e1. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/212/5/more‐refresh‐required‐closing‐gap‐indigenous‐health‐inequality

Abstract

Objective: To explore the values of Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory during their perioperative journey.

Design: A community‐based participatory action research approach was used, integrating yarning, deep listening and reflection methods to gather qualitative data in culturally appropriate ways. Data collection involved two yarning circles followed by interpretation and triangulation sessions with co‐researchers.

Setting: Conducted in non‐health care settings in Garramilla (Darwin) between May 2023 and September 2024, the study included participants from urban, regional and remote NT Aboriginal communities.

Participants: Purposive and snowball sampling were used to engage 18 participants with lived experience of surgery, who share expertise in renal health journeys and have kinship ties spanning from Saltwater Country to Desert Country, with diverse age, language and gender representation.

Main outcome measures: Thematic insights into what First Nations peoples in the NT value during the perioperative journey, to inform culturally safe models of care.

Results: Respect emerged as the core principle in the perioperative journey, with family involvement, cultural practices and effective communication identified as key elements. Respect was evident in honouring cultural protocols, integrating traditional healing practices and recognising patient autonomy. Family involvement was highlighted as essential, with kinship ties influencing shared decision‐making processes and support throughout the perioperative experience. Culturally competent communication, including the use of interpreters and clear explanations, played a critical role in bridging cultural differences and ensuring shared understanding. Together, these elements fostered a sense of safety, belonging and empowerment. Ultimately, trust was identified as an overarching outcome that unified these interconnected values, enhancing patient comfort, engagement and overall satisfaction in the perioperative journey.

Conclusion: Respect is integral to Aboriginal people in the perioperative journey, and they value family, culture and communication when navigating surgery. When these values coalesce, trust is generated. These findings highlight the need to integrate culturally informed, patient‐centred care models that prioritise respect and trust building to improve accessibility, experience and surgical outcomes.