The known: Intimate partner violence is a public health problem with implications for clinical practice and public policy. Information about the prevalence of intimate partner violence in Australia, including differences by gender, age, and sexual orientation, is limited.

The new: Intimate partner physical, sexual, and psychological violence is widespread. In our survey, significantly more women reported experiencing each type of violence than men (any intimate partner violence: 48.4% v 40.4%). More non‐heterosexual people reported intimate partner violence than heterosexual people (70.2% v 43.1%).

The implications: The lifetime prevalence of experiencing intimate partner violence is high, especially among women. Improved prevention is needed in the areas of health care, welfare, and justice.

The World Health Organization defines intimate partner violence as “behaviour by an intimate partner or ex‐partner that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviours.”1 The prevalence and severity of experienced intimate partner violence are greater for women than for men.2 The United Nations Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women3 and target 5.2 of its Sustainable Development Goals4 aim to eradicate intimate partner violence.5

In Australia, major government initiatives introduced since 2010 aim to improve the understanding and prevention of intimate partner violence.6,7 While it affects women, men, and people of diverse genders, national policy acknowledges that most victims are women and that women are more likely than men to experience more severe violence. The National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022–2032 aims “to end gender‐based violence in one generation.”6 Recent reforms have established criminal offences for intimate partner violence within domestic relationships (eg, the New South Wales Crimes Legislation Amendment (Coercive Control) Act 20228). This ends centuries of legal doctrine that protected violence by men against women in the private sphere, inaugurating a new era in which gender equality and freedom from violence are fundamental societal principles.

These policy initiatives reflect the consensus that intimate partner violence is a major public health problem with significant and enduring impacts on women's health.9,10 It is a leading cause of femicide worldwide,11 and it is strongly associated with mental disorders,12,13 drug and alcohol problems,14,15 and suicide attempts,12,16,17 as well as physical conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and chronic pain.14

Intimate partner violence poses challenges for health policy, general practice, specialised clinical care, and the development of practitioner education that is trauma‐informed, violence‐informed, and gender‐informed.14,17 Health systems must be able to respond to individual women and women at particular risk.17 Reliable and comprehensive population‐based information about its prevalence is fundamental to understanding and preventing intimate partner violence and developing clinical responses.

The global prevalence of intimate partner violence, particularly of violence against women, is concerning;18,19,20 the lifetime prevalence among women of physical or sexual intimate partner violence is estimated to be 30%18 or 27%.19 However, it is increasingly recognised that prevalence studies should use validated measures to assess at least three types of intimate partner violence: physical, sexual, and psychological violence.12,14,20,21,22 Rigorously tested instruments for this purpose include the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS)23,24 and the Composite Abuse Scale–Revised (short form).25

Studies of intimate partner violence in Australia have adopted different approaches. Several have used the CAS (but not to determine population‐wide prevalence), including the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health (ALSWH), which investigated consistency of reporting and health outcomes26,27 and associations between intimate partner violence and diverse outcomes.28,29 Other research using the CAS has examined intimate partner violence in groups at particular risk,30 and intimate partner violence during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic.31

The most reliable estimates of the prevalence of intimate partner violence in Australia have been based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics Personal Safety Survey (PSS).32 However, the PSS does not employ a validated scale and covers a restricted range of behaviours. For example, “intimate partners” includes only partners who live together; “sexual violence” excludes unwanted sexual touching and is limited to forced or attempted forced sexual activity against the person's will; and physical and emotional violence items are confined to actions in which the perpetrator intended to cause harm. In 2021–22, the PSS found that the lifetime prevalence of physical or sexual abuse was 23% for women and 7.3% for men, of emotional abuse 23% for women and 14% for men, and of economic abuse 16% for women and 7.8% for men.32

Important gaps in our knowledge about the prevalence and nature of intimate partner violence remain, both in Australia and overseas.12,14,19,33,34 No Australian survey with a nationally representative sample and using a validated instrument has estimated the prevalence of a broad spectrum of intimate partner violence, including multitype intimate partner violence, across all intimate relationships. Further, little is known about differences in prevalence by gender, age group, or sexual orientation. A survey of a large nationally representative sample that captured the lifetime experiences of diverse types of intimate partner violence could help close these knowledge gaps.

The primary aim of our study was to estimate the national prevalence of intimate partner violence in Australia by surveying a nationally representative sample of people, using a psychometrically validated instrument. We also estimated the national prevalence of multitype intimate partner violence and of each specific intimate partner violence type, and examined differences by gender, age group, and sexual orientation.

Methods

Our survey was undertaken as part of the Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS). The aims of the ACMS were to estimate the prevalence of child maltreatment and of associated mental disorders, health risk behaviours, and burden of disease.35 The ACMS also provided an opportunity to explore intimate partner violence. As detailed elsewhere,36 8503 participants aged 16 years or older were recruited for the ACMS mobile telephone survey during 9 April – 11 October 2021 by a professional survey company, the Social Research Centre (https://srcentre.com.au) using random mobile phone digit dial technology and advance text messaging. The demographic characteristics of the participant group were similar to those of the Australian population in 201637 with respect to gender, Indigenous status, region (metropolitan, regional/rural) and remoteness category of residence,38 and marital status, but larger proportions of participants were born in Australia, lived in areas of higher socio‐economic status (Index of Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage, IRSAD39), had tertiary qualifications, or had income exceeding $1250 per week. Population weights were derived to adjust for these differences (Supporting Information, table 1). We report our study according to the Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS).40

Measures

The ACMS administered the Composite Abuse Scale (Revised)–Short Form (CASR‐SF), a validated and reliable measure of intimate partner violence.25 The CASR‐SF comprises fifteen behaviour‐specific questions (yes/no responses) about experiences of intimate partner violence (five questions about physical violence; two about sexual violence; and eight about psychological violence). The items were introduced with a preamble that asked the participant to indicate whether any intimate partner had ever inflicted any of the acts on them.

Sex and gender were assessed with the question, “How would you define your gender?” Responses were coded using a list of fourteen options, including “female/woman” and “male/man”. For this report, we categorised participants who did not select either of these options as being of diverse gender.

Procedures

Study procedures have been reported elsewhere.36 In brief, the 8503 participants included 3500 participants aged 16–24 years, and about 1000 participants each aged 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, or 65 years or older. The sample, including the oversampled 16–24‐year‐old age group, met the research aims of both the ACMS and our survey. Data from the computer‐assisted telephone interview (CATI) software platform were imported into SAS 9.4; data cleaning was undertaken by authors DML and MM.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the prevalence of any intimate partner violence for the entire participant group, and by gender, age group, and sexual orientation. For each intimate partner violence type, we adopted methods congruent with the instrument25 and other studies,30 generating estimated prevalence based on positive endorsement of any of the screeners. For the prevalence of multitype intimate partner violence, we aggregated data for people who experienced two or all three of the three intimate partner violence types. We calculated prevalence rates at the whole of population level for people who had ever been in an intimate relationship since the age of 16 years, including all whose marital status was married, separated, divorced, or living together but not married or widowed; it also included those who were single or never married, but who had ever “been in an adult intimate relationship”, defined as being in a romantic relationship when aged 16 years or older.

Survey‐weighted data were summarised as numbers and proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated using the Taylor series method. We compared each type of intimate partner violence by gender, sexual orientation, and age group; statistical significance of between group differences was defined as non‐overlap of the 95% CIs. We also compared prevalence estimates for participants aged 25–44 years and those aged 45 years or older using the Rao–Scott χ2 test for survey data; more than 90% of participants in these two age groups had had intimate partners, but 42% of people aged 16–24 years had not. Missing responses were treated as “no” responses. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4; graphs were prepared in Stata 17. All analyses were checked independently by two authors, by random spot checking of the SAS coding and replicating analyses in SPSS 28.

Ethics approval

The ACMS, including the separately funded intimate partner violence component, was approved by the Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee (#1900000477). Each survey participant provided verbal informed consent to participation.

Results

Of the 404 180 people we attempted to contact by phone, 210 373 would have been eligible to participate in our survey; contact was made with 60 803 eligible persons, of whom 8503 completed the ACMS survey (Supporting Information, table 1). The response rate among eligible candidates contacted by phone was 14.0%; based on the total number of eligible candidates, including those not contacted, it was 4.0%. Potential participation bias, as indicated by number of calls required to complete the survey, was deemed to be minor.36

Of the 8503 respondents, 21 (0.25%) did not report whether they had ever been in intimate partner relationships and were not asked questions about intimate partner violence. Of the remaining 8482 participants, 8357 (98.5%) identified as female/woman or male/man; 7022 (unweighted proportion, 82.6%; weighted proportion, 90.9%) had had intimate partners at some point since age sixteen years, including 2201 of 3493 people aged 16–24 years (weighted proportion, 56.9%; women, 59.7%; men, 54.2%; diverse genders, 54.6%) 1868 of 1993 people aged 25–44 years (92.9%; women, 96.0%; men, 89.9%; diverse genders, 92.9%), and 2953 of 2996 people aged 45 years or older (98.5%; women, 98.9%; men, 98.1%) (Supporting Information, table 2).

Prevalence of intimate partner violence, by gender and sexual orientation

All proportions reported from this point are weighted proportions. A total of 3170 participants reported ever experiencing intimate partner violence since the age of 16 years (44.8%; 95% CI, 43.3–46.2%); the proportion was significantly larger for women (48.4%; 95% CI, 46.3–50.4%) than men (40.4%; 95% CI, 38.3–42.5%). Sixty‐two of 88 participants of diverse genders reported experiencing intimate partner violence (69%; 95% CI, 55–83%) (Box 1).

The proportion of participants who reported ever experiencing intimate partner violence was significantly larger for those of non‐heterosexual orientation (70.2%; 95% CI, 65.7–74.7%) than for participants of heterosexual orientation (43.1%; 95% CI, 41.6–44.6%) (Box 2).

Prevalence of types of intimate partner violence, by gender

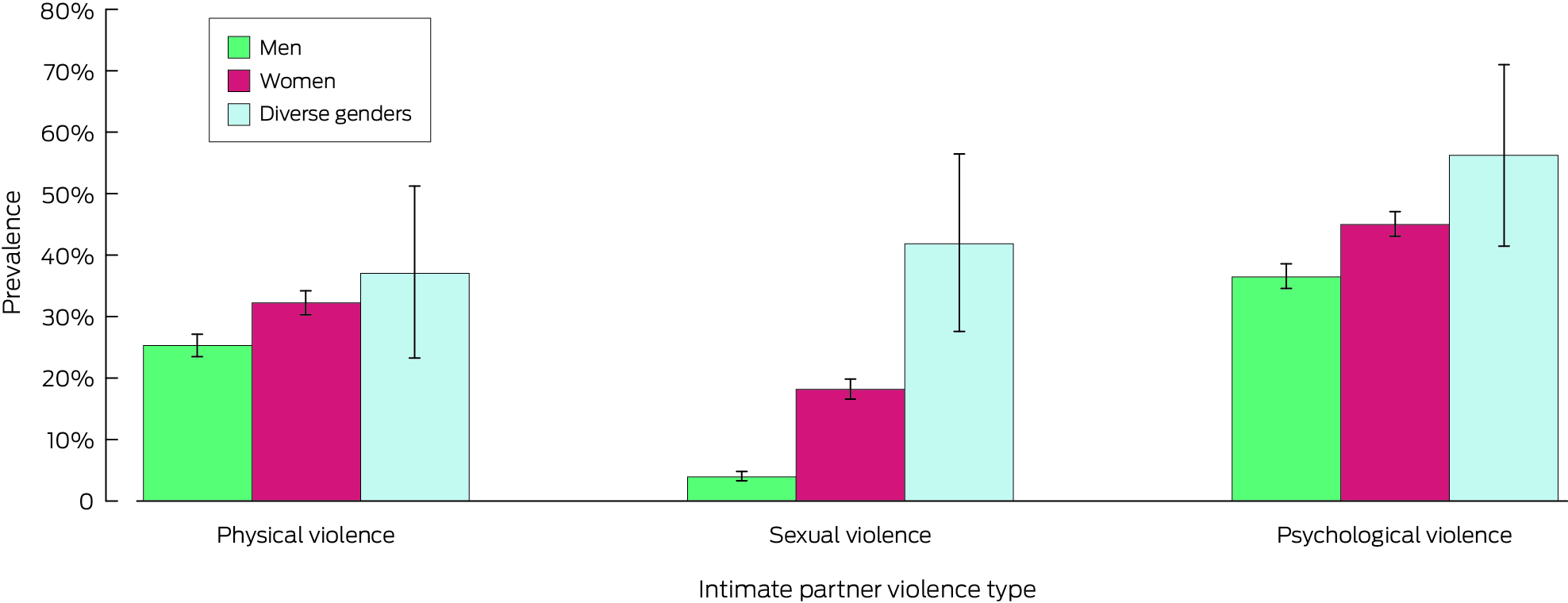

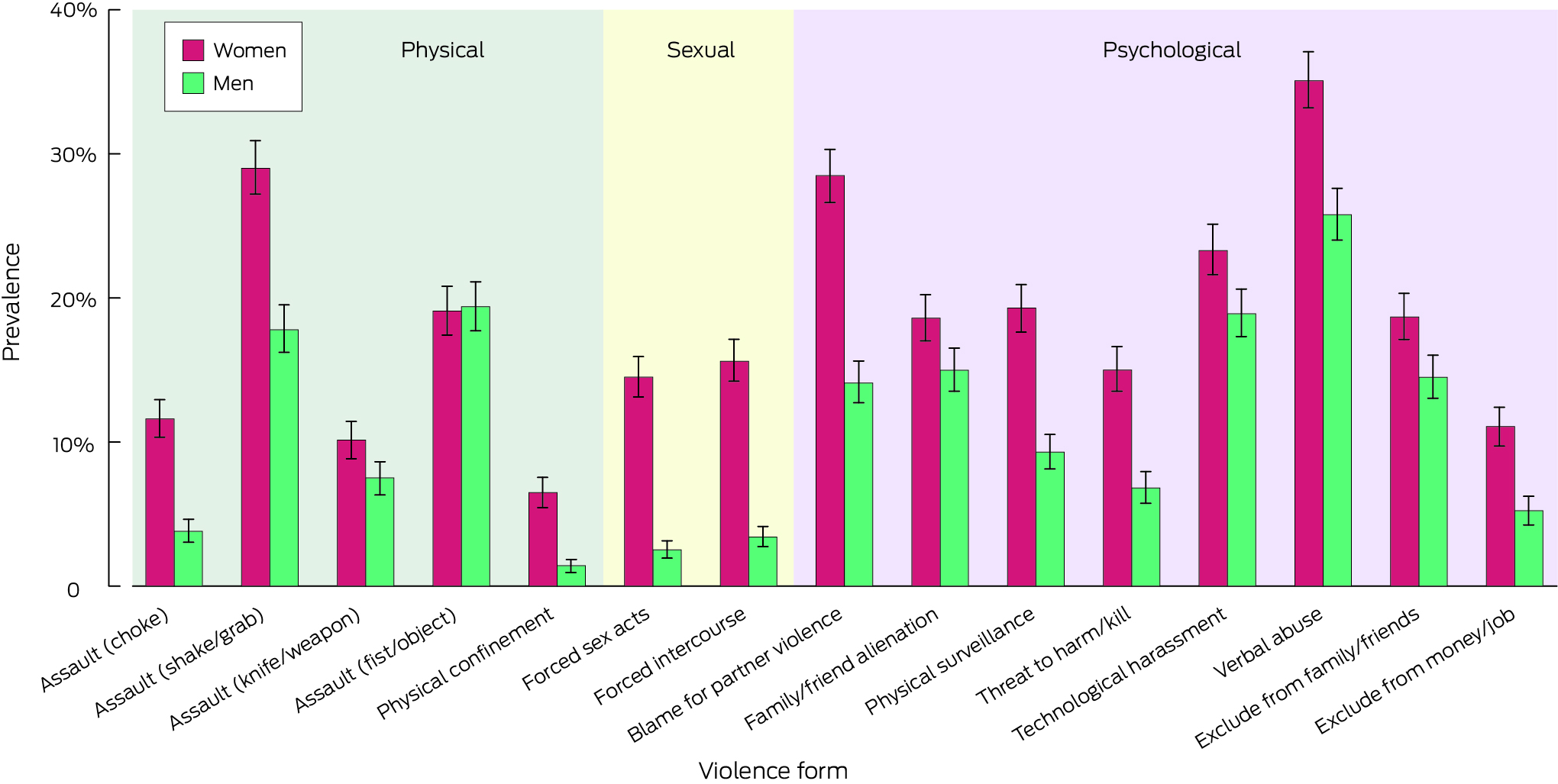

A total of 1889 participants reported intimate partner physical violence (29.1%; 95% CI, 27.7–30.4%); the proportion was significantly larger for women (32.3%; 95% CI, 30.3–34.2%) than for men (25.4%; 95% CI, 23.5–27.2%) (Box 3, Box 4). The prevalence of four of the five types of physical violence were higher for women, including being choked (women: 11.6%, 95% CI, 10.3–12.9%; men: 3.8%: 95% CI, 3.0–4.6%) and actual or threatened harm by a knife, gun, or weapon (women: 10.1%, 95% CI, 8.8–11.4%; men: 7.5%, 95% CI, 6.3–8.6%) (Box 5; Supporting Information, table 4).

A total of 925 participants reported intimate partner sexual violence (11.7%; 95% CI, 10.8–12.7%); the proportion was significantly larger for women (18.2%; 95% CI, 16.6–19.8%) than for men (4.0%; 95% CI, 3.3–4.8%) (Box 3, Box 4). The prevalence of both types of sexual violence were higher for women: forced sex or attempted forced sex (women: 15.6%; 95% CI, 14.2–17.1%; men: 3.4%, 95% CI; 2.7–4.1%), and being made to perform sex acts they did not want to (women: 14.5%; 95% CI, 13.1–15.9%; men: 2.5%; 95% CI, 1.9–3.1%) (Box 5; Supporting Information, table 5).

A total of 2897 participants reported intimate partner psychological violence (41.2%; 95% CI, 39.8–42.6%); the proportion was significantly larger for women (45.1%; 95% CI, 43.1–47.1%) than for men (36.6%; 95% CI, 34.6–38.6%) (Box 3, Box 4). The prevalence of all eight types of psychological violence were higher for women (Box 5; Supporting Information, table 6).

Prevalence of intimate partner violence, by age

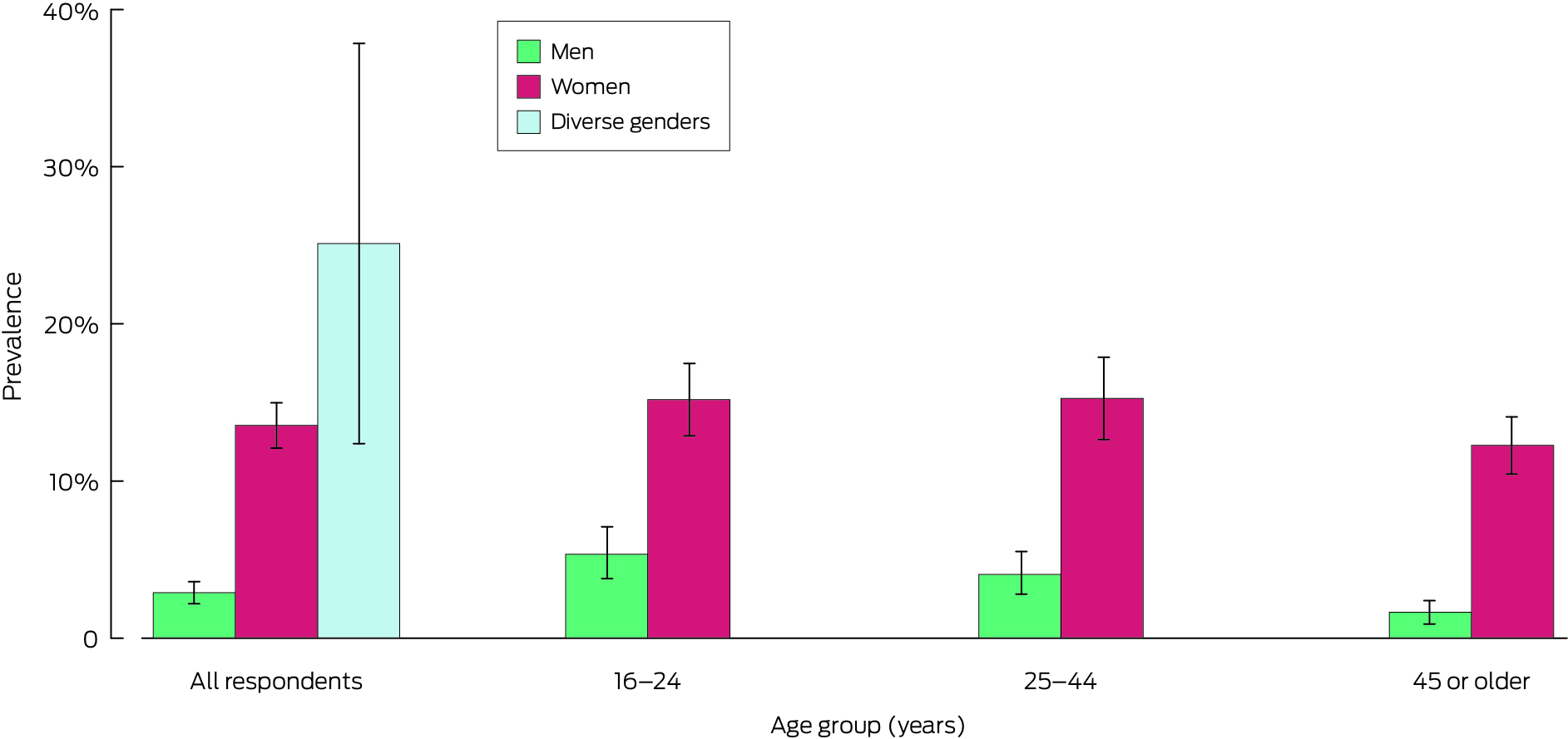

A significantly larger proportion of participants aged 25–44 years reported ever experiencing intimate partner violence (51.4%; 95% CI, 48.9–53.9%) than of participants aged 45 years or older (39.9%; 95% CI, 37.9–41.9%). A total of 1056 participants aged 16–24 years reported any intimate partner violence (48.4%, 95% CI, 46.1–50.6%) (Box 1).

Prevalence of multitype intimate partner violence

A total of 1925 participants reported two or more types of intimate partner violence (28.6%; 95% CI, 27.2–29.9%); the proportion was significantly larger for women (33.7%; 95% CI, 31.7–35.6%) than for men (22.7%; 95% CI, 20.9–24.5%) (Box 6). The proportion of respondents who reported all three intimate partner violence types was also significantly larger for women (13.6%; 95% CI, 12.1–15.0) than for men (2.9%; 95% CI, 2.2–3.6) and by age group (Box 7). A total of 2185 participants at least one of physical or sexual violence (32.0%; 95% CI, 30.7‐33.4%); the proportion was significantly larger for women (36.7%; 95% CI, 34.8–38.7%) than men (26.5%; 95% CI, 24.6–28.3%) (Supporting Information, table 8).

Discussion

We report national prevalence estimates for the lifetime experience of intimate partner violence, both overall and by type: physical, sexual, and psychological. Using a validated instrument and a large nationally representative sample, we found that 44.8% of respondents aged 16 years or older had experienced intimate partner violence. The comprehensive survey covered experiences during all intimate partner relationships, and a broad range of types and forms of intimate partner violence. We found that the prevalence of experiencing physical, sexual, and psychological violence among women was higher than reported by an Australian survey that captured information only on violence by cohabiting partners and that excluded some types of violence.32 Further, we found the prevalence of experience of physical or sexual violence among women (36.7%) was higher than published estimates of its worldwide prevalence (30.0%,18 27.0%19).

The prevalence of intimate partner violence experienced by women is particularly concerning. A significantly larger proportion of women than men reported experiencing any intimate partner violence, both overall (48.4% v 40.4%) and for all three types. Physical violence was reported by 32.3% of women, sexual violence by 18.2%, and psychological violence by 45.1%. Intimate partner violence clearly remains a major public health problem that requires more effective and comprehensive public health solutions.

Substantial proportions of men reported physical (25.4%) and psychological intimate partner violence (36.6%). Physical violence against men by women can involve retaliatory or defensive responses to intimate partner violence by their partners, and can be less severe than violence inflicted by men.41 It is possible that much physical violence by women against men is “situational couple violence” rather than the ongoing “intimate terrorism” that comprises a substantial proportion of intimate partner violence against women.42 The prevalence of specific forms of physical violence in our survey indicated that men experienced severe physical violence less frequently than women (eg, choking: men, 3.8% v women, 11.6%; violence with a knife, gun, or weapon: men, 7.5% v women, 10.1%). Being hit with a fist or object or being kicked or bitten was reported by 19.4% of male respondents, and being shaken, pushed, grabbed, or thrown by 17.8%; these forms of violence could be inflicted in the context of situational couple violence. The experiences of men should not be dismissed, but the prevalence of any intimate partner violence, each intimate partner violence type, multitype intimate partner violence, and fourteen of the fifteen specific violence forms was significantly higher for women than men (Box 5).

Our findings regarding multitype intimate partner violence indicate that women experience more varied intimate partner violence than men: 33.7% of women experienced two or three types of intimate partner violence, compared with 22.7% of men, and 13.6% of women experienced all three types, compared with 2.9% of men (Box 6). Regardless of whether the different violence types were inflicted by one or by several perpetrators, this cumulative experience of violence is concerning, given the likelihood of especially poor health consequences for people who experience multiple types of intimate partner violence.33

Analysis by age group suggests that the prevalence of intimate partner violence has not declined. Cross‐sectional surveys of lifetime intimate partner violence typically find that the reported prevalence is higher among younger participants, despite their having had less time to be in relationships and the expectation that cumulative prevalence would increase with time.41 Younger people may be particularly exposed to intimate partner violence, and some older participants may not recall less serious or isolated incidents.43 Whatever the impact of these factors, we found that the prevalence of intimate partner violence among participants aged 25–44 years was significantly higher (51.4%) than for those aged 45 years or older (39.9%); and it was significantly higher for women aged 25–44 years (53.8%) than for women aged 45 years or older (44.3%). The prevalence among women aged 16–24 years (52.5%), was similar to that for women aged 25–44 years. Among all participants aged 16–24 years, 48.4% had experienced intimate partner violence, including physical violence (25.2%) and sexual violence (18.2%). These age group findings, especially those for women, indicate that intimate partner violence remains a major problem in Australian society.

Our study is one of the few to examine lifetime intimate partner violence experienced by non‐heterosexual people.34 Its prevalence was higher among non‐heterosexual (70.2%) than heterosexual participants (43.1%). The small number of non‐heterosexual participants who had been in intimate relationships (494 people) constrains interpretation of this finding, and further research is needed. Similarly, the prevalence of intimate partner violence experienced by people of diverse genders (69%) was higher than for women, but the small number of respondents (88 people) again means that further research is required before drawing conclusions.

We collected data from a large, nationally representative sample of Australians, obtaining rigorous population‐wide data about the lifetime prevalence of intimate partner violence. We used a psychometrically validated instrument, ensuring robust and comprehensive measurement of multiple forms of intimate partner violence, capturing their full extent without excluding important types of violence. We explicitly assessed psychological violence, an important and neglected form of intimate partner violence.2,19,44 We captured intimate partner violence inflicted by all intimate partners, not only those with whom the victim lived, generating a more complete picture of intimate partner violence in Australia.

Limitations

The retrospective design of our study may have introduced recall bias,42 leading to conservative prevalence estimates. Some experiences may have been cognitively reframed by individual participants as normal, also reducing prevalence. We did not assess the frequency or intensity of intimate partner violence; our primary aim was to estimate lifetime prevalence of intimate partner violence, but the prevalence of specific forms could provide insights about severity. The COVID‐19 pandemic may have influenced the prevalence of some forms of intimate partner violence,31 but any association with the onset or intensification of existing intimate partner violence is unlikely to have substantially affected lifetime prevalence. As our purpose was to provide population‐wide prevalence estimates, we did not assess prevalence by ethnic background or Indigenous status; in any case, small participant numbers in these categories precluded such analyses. Further analyses by Indigenous status should be considered only in studies by Indigenous research teams, and designed by, with, and for Indigenous communities. Finally, we did not take an intersectional approach to assessing the relationship between multiple social categories and intimate partner violence.

Conclusion

Intimate partner violence is widespread in Australia. The prevalence of all types of intimate partner violence is significantly higher among women than men. National intimate partner violence prevention strategies have not yet achieved their objectives; they should be strengthened by a comprehensive, long term approach to responding to risk factors, including social and economic conditions, together with long standing societal and structural discrimination against women, prejudicial social norms, and diverse individual risk factors for violence by men.9 Health systems and clinical practice can also contribute to primary prevention and early intervention by assisting individuals and people in groups at particular risk of violence. Practitioner education and system change is required to support violence‐informed, trauma‐informed, and gender‐informed patient care.9,10,17 Intimate partner violence should be further investigated, including its chronicity and contexts, to monitor trends and identify areas of specific need.

Box 1 – Lifetime experience of any intimate partner violence among 7022 respondents with intimate partners at any time since age 16 years, overall and by age group and gender*

|

Age group |

Respondents |

Number reporting experience |

Proportion (95% CI)† |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

All respondents |

7022 |

3170 |

44.8% (43.3–46.2%) |

||||||||||||

|

Women |

3558 |

1763 |

48.4% (46.3–50.4%) |

||||||||||||

|

Men |

3376 |

1345 |

40.4% (38.3–42.5%) |

||||||||||||

|

Diverse genders |

88 |

62 |

69% (55–83%) |

||||||||||||

|

16–24 years |

2201 |

1056 |

48.4% (46.1–50.6%) |

||||||||||||

|

Women |

1099 |

576 |

52.5% (49.3–55.7%) |

||||||||||||

|

Men |

1048 |

442 |

42.8% (39.5–46.1%) |

||||||||||||

|

Diverse genders |

54 |

38 |

71% (58–83%) |

||||||||||||

|

25–44 years |

1868 |

928 |

51.4% (48.9–53.9%) |

||||||||||||

|

Women |

945 |

499 |

53.8% (50.3–57.3%) |

||||||||||||

|

Men |

903 |

414 |

48.5% (44.8–52.1%) |

||||||||||||

|

45 years or older |

2953 |

1186 |

39.9% (37.9–41.9%) |

||||||||||||

|

Women |

1514 |

688 |

44.3% (41.5–47.1%) |

||||||||||||

|

Men |

1425 |

489 |

34.6% (31.9–37.4%) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval. * Rao Scott test of association between gender or age group and lifetime experience of intimate partner violence: each P < 0.001. The numbers and proportions of respondents who experienced the three types of intimate partner violence are reported in the Supporting Information, table 3; the numbers and proportions did not provide responses for specific items are reported in the Supporting Information, table 4. † Weighted by age group, sex, Indigenous status, country of birth (Australia or overseas), highest educational level, and residential socio‐economic status (Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage quintile). |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Lifetime experience of any intimate partner violence among 7022 respondents with intimate partners at any time since age 16 years, overall and by age group and sexual orientation*

|

Age group |

Respondents |

Number reporting experienc |

Proportion (95% CI)† |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

All respondents |

7022 |

3170 |

44.8% (43.3–46.2%) |

||||||||||||

|

Heterosexual |

6214 |

2650 |

43.1% (41.6–44.6%) |

||||||||||||

|

Diverse sexualities |

730 |

494 |

70.2% (65.7–74.7%) |

||||||||||||

|

Do not know/no response |

78 |

— |

— |

||||||||||||

|

16–24 years |

2201 |

1056 |

48.4% (46.1–50.6%) |

||||||||||||

|

Heterosexual |

1759 |

770 |

44.5% (41.9–47.0%) |

||||||||||||

|

Diverse sexualities |

433 |

282 |

64.1% (59.1–69.1%) |

||||||||||||

|

25–44 years |

1868 |

928 |

51.4% (48.9–53.9%) |

||||||||||||

|

Heterosexual |

1653 |

785 |

49.6% (47.0–52.3%) |

||||||||||||

|

Diverse sexualities |

189 |

136 |

71.9% (64.8–79.0%) |

||||||||||||

|

45 years or older |

2953 |

1186 |

39.9% (37.9–41.9%) |

||||||||||||

|

Heterosexual |

2802 |

1095 |

38.9% (36.9–41.0%) |

||||||||||||

|

Diverse sexualities |

108 |

76 |

72.7% (62.9–82.4%) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval. * Rao Scott χ2 test of association between sexual orientation and lifetime experience of intimate partner violence, both overall and for each age group: each P < 0.001. † Weighted by age group, sex, Indigenous status, country of birth (Australia or overseas), highest educational level, and residential socio‐economic status (Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage quintile). |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Lifetime experience of intimate partner violence types among 7022 respondents with intimate partners at any time since age 16 years, overall and by age group and gender*

|

|

|

Physical violence |

Sexual violence |

Psychological violence |

|||||||||||

|

Age group |

Respondents |

Number |

Proportion (95% CI)† |

Number |

Proportion (95% CI)† |

Number |

Proportion (95% CI)† |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

All respondents |

7022 |

1889 |

29.1% (27.7–30.4%) |

925 |

11.7% (10.8–12.7%) |

2897 |

41.2% (39.8–42.6%) |

||||||||

|

Women |

3558 |

1068 |

32.3% (30.3–34.2%) |

711 |

18.2% (16.6–19.8%) |

1631 |

45.1% (43.1–47.1%) |

||||||||

|

Men |

3376 |

788 |

25.4% (23.5–27.2%) |

175 |

4.0% (3.3–4.8%) |

1216 |

36.6% (34.6–38.6%) |

||||||||

|

Diverse genders |

88 |

33 |

37% (23–51%) |

39 |

42% (28–56%) |

50 |

56% (42–71%) |

||||||||

|

16–24 years |

2201 |

530 |

25.2% (23.2–27.2%) |

401 |

18.2% (16.5–20.0%) |

964 |

44.2% (42.0–46.5%) |

||||||||

|

Women |

1099 |

287 |

26.8% (24.0–29.6%) |

286 |

25.8% (23.0–28.6%) |

529 |

48.4% (45.2–51.6%) |

||||||||

|

Men |

1048 |

222 |

22.6% (19.7–25.5%) |

89 |

8.5% (6.5–10.4%) |

405 |

39.3% (36.0–42.5%) |

||||||||

|

25–44 years |

1868 |

564 |

33.0% (30.6–35.4%) |

252 |

13.9% (12.2–15.7%) |

866 |

48.2% (45.7–50.7%) |

||||||||

|

Women |

945 |

301 |

34.8% (31.4–38.2%) |

185 |

20.8% (17.9–23.7%) |

474 |

51.5% (47.9–55.0%) |

||||||||

|

Men |

903 |

257 |

31.0% (27.6–34.4%) |

57 |

5.9% (4.3–7.5%) |

378 |

44.4% (40.7–48.0%) |

||||||||

|

45 years or older |

2953 |

795 |

27.1% (25.3–28.9%) |

272 |

9.3% (8.1–10.5%) |

1067 |

36.2% (34.2–38.1%) |

||||||||

|

Women |

1514 |

480 |

31.5% (28.8–34.1%) |

240 |

15.5% (13.4–17.5%) |

628 |

40.7% (37.9–43.4%) |

||||||||

|

Men |

1425 |

309 |

22.0% (19.6–24.4%) |

29 |

2.1% (1.3–3.0%) |

433 |

31.0% (28.3–33.7%) |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval. * Rao Scott χ2 test of association between gender and each intimate partner violence type: each P < 0.001. † Weighted by age group, sex, Indigenous status, country of birth (Australia or overseas), highest educational level, and residential socio‐economic status (Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage quintile). |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Lifetime experience of intimate partner violence types among 7022 respondents with intimate partners at any time since age sixteen, by gender*

* The data for this graph are included in Box 3. Proportions are weighted by age group, sex, Indigenous status, country of birth (Australia or overseas), highest educational level, and residential socio‐economic status (Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage quintile).

Box 5 – Lifetime experience of specific forms of intimate partner violence types among 7022 respondents with intimate partners at any time since age 16 years, by gender*

* The data for this graph are included in Supporting Information, tables 5 to 7. Proportions are weighted by age group, sex, Indigenous status, country of birth (Australia or overseas), highest educational level, and residential socio‐economic status (Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage quintile).

Box 6 – Lifetime experience of multitype intimate partner violence among 7022 respondents with intimate partners at any time since age 16 years, overall and by age group and gender*

|

|

|

Multitype intimate partner violence |

Two types |

Three types |

|||||||||||

|

Age group |

Respondents |

Number |

Proportion (95% CI)† |

Number |

Proportion (95% CI)† |

Number |

Proportion (95% CI)† |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

All respondents |

7022 |

1925 |

28.6% (27.2–29.9%) |

1309 |

19.9% (18.7–21.1%) |

616 |

8.6% (7.8–9.5%) |

||||||||

|

Women |

3558 |

1169 |

33.7% (31.7–35.6%) |

691 |

20.1% (18.5–21.7%) |

478 |

13.6% (12.1–15.0%) |

||||||||

|

Men |

3376 |

718 |

22.7% (20.9–24.5%) |

602 |

19.8% (18.1–21.5%) |

116 |

2.9% (2.2–3.6%) |

||||||||

|

Diverse genders |

88 |

38 |

41% (27–56%) |

16 |

16% (6.5–26%) |

22 |

25% (12–38%) |

||||||||

|

16–24 years |

2201 |

606 |

28.3% (26.2–30.4%) |

373 |

17.4% (15.6–19.1%) |

233 |

10.9% (9.5–12.4%) |

||||||||

|

Women |

1099 |

362 |

33.2% (30.2–36.3%) |

198 |

18.0% (15.6–20.5%) |

164 |

15.2% (12.9–17.5%) |

||||||||

|

Men |

1048 |

220 |

22.1% (19.3–24.9%) |

166 |

16.7% (14.1–19.2%) |

54 |

5.4% (3.8–7.1%) |

||||||||

|

Diverse genders |

54 |

24 |

46% (32–60%) |

9 |

17% (6.0–28%) |

15 |

29% (16–42%) |

||||||||

|

25–44 years |

1868 |

583 |

33.6% (31.2–36.0%) |

412 |

23.5% (21.3–25.7%) |

171 |

10.1% (8.5–11.7%) |

||||||||

|

Women |

945 |

335 |

38.0% (34.5–41.4%) |

209 |

22.7% (19.8–25.7%) |

126 |

15.3% (12.6–17.9%) |

||||||||

|

Men |

903 |

238 |

28.6% (25.3–32.0%) |

198 |

24.5% (21.3–27.7%) |

40 |

4.1% (2.8–5.5%) |

||||||||

|

45 years or older |

2953 |

736 |

25.3% (23.6–27.1%) |

524 |

18.0% (16.4–19.5%) |

212 |

7.3% (6.3–8.4%) |

||||||||

|

Women |

1514 |

472 |

31.0% (28.4–33.7%) |

284 |

18.8% (16.5–21.0%) |

188 |

12.3% (10.4–14.1%) |

||||||||

|

Men |

1425 |

260 |

18.8% (16.6–21.1%) |

238 |

17.1% (15.0–19.3%) |

22 |

1.7% (0.9–2.4%) |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval. * Rao‐Scott χ2 test of association between gender or age group and multitype intimate partner violence: each P < 0.001. The experience of each combination of intimate sexual partner violence type, extrapolated to the entire Australian population, is depicted in the Supporting Information, figure 1. † Weighted by age group, sex, Indigenous status, country of birth (Australia or overseas), highest educational level, and residential socio‐economic status (Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage quintile). |

|||||||||||||||

Box 7 – Lifetime experience of all three types of intimate partner violence among 7022 respondents with intimate partners at any time since age 16 years, overall and by age group and gender*

* The data for this graph are included in Box 6. Proportions are weighted by age group, sex, Indigenous status, country of birth (Australia or overseas), highest educational level, and residential socio‐economic status (Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage quintile).

Received 2 August 2024, accepted 23 December 2024

- Ben Mathews1,2

- Kelsey L Hegarty3,4

- Harriet L MacMillan5

- Monica Madzoska6

- Holly E Erskine7,8

- Rosana Pacella9

- James G Scott10

- Hannah Thomas7,11

- Franziska Meinck12

- Daryl Higgins13

- David M Lawrence6

- Divna Haslam14

- Sara Roetman1

- Eva Malacova15

- Timothy Cubitt16

- 1 Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD

- 2 Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, United States of America

- 3 Safer Families Centre, the University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

- 4 Family Violence Prevention Centre, the Royal Women's Hospital, Melbourne, VIC

- 5 McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

- 6 Curtin University, Perth, WA

- 7 The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

- 8 Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research, Brisbane, QLD

- 9 Institute for Lifecourse Development, University of Greenwich, London, United Kingdom

- 10 Child Health Research Centre, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

- 11 Centre for Mental Health Treatment Research and Education, Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research, Brisbane, QLD

- 12 University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- 13 Institute of Child Protection Studies, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, VIC

- 14 Parenting and Family Support Centre, the University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

- 15 QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Brisbane, QLD

- 16 Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra, ACT

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Queensland University of Technology, as part of the Wiley – Queensland University of Technology agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Data Sharing:

Final data sets will be stored on the Australian Data Archive and made available in January 2026 after an embargo period.

This study was supported by the Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS), funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council project grant (APP1158750) during 2019–2023, with further funding from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, and the Department of Social Services. The Australian Institute of Criminology provided funding to support the inclusion of survey items on intimate partner violence. The funding sources played no role in study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation, reporting or publication, except for the scholarly collaboration by one author (Timothy Cubitt). We acknowledge all survey participants, whose responses facilitated this research.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. World Health Organization. Violence against women. 25 Mar 2024. https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/violence‐against‐women (viewed May 2024).

- 2. World Health Organization. RESPECT women: preventing violence against women. 6 Apr 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO‐RHR‐18.19 (viewed May 2024).

- 3. United Nations. Declaration on the elimination of violence against women [General Assembly resolution 48/104]. 20 Dec 1993. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments‐mechanisms/instruments/declaration‐elimination‐violence‐against‐women (viewed May 2024).

- 4. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls [Sustainable development goal 5]. Geneva: United Nations, 2015. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal5 (viewed May 2024).

- 5. World Health Organization. Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence. 10 Jan 2010. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564007 (viewed May 2024).

- 6. Council of Australian Governments. The national plan to end violence against women and children 2022–2032. Updated 24 Mar 2025. https://www.dss.gov.au/national‐plan‐end‐gender‐based‐violence/resource/national‐plan‐end‐violence‐against‐women‐and‐children‐2022‐2032 (viewed May 2024).

- 7. Australian Attorney‐General's Department. The national principles to address coercive control in family and domestic violence. Updated 5 Mar 2024. https://www.ag.gov.au/families‐and‐marriage/publications/national‐principles‐address‐coercive‐control‐family‐and‐domestic‐violence (viewed May 2024).

- 8. Government of New South Wales. Crimes legislation amendment (coercive control) Act 2022 (no. 65). 23 Nov 2022. https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/pdf/asmade/act‐2022‐65 (viewed Apr 2025).

- 9. García‐Moreno C, Hegarty K, d'Oliveira AFL, et al. The health‐systems response to violence against women. Lancet 2015; 385: 1567‐1579.

- 10. García‐Moreno C, Zimmerman C, Morris‐Gehring A, et al. Addressing violence against women: a call to action. Lancet 2015; 385: 1685‐1695.

- 11. Stöckl H, Devries K, Rotstein A, et al. The global prevalence of intimate partner homicide: a systematic review. Lancet 2013; 382: 859‐865.

- 12. White SJ, Sin J, Sweeney A, et al. Global prevalence and mental health outcomes of intimate partner violence among women: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse 2023; 25: 494‐511.

- 13. Ellsberg M, Jansen HAFM, Heise L, et al. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi‐country study on women's health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet 2008; 371: 1165‐1172.

- 14. Stubbs A, Szoeke C. The effect of intimate partner violence on the physical health and health‐related behaviors of women: a systematic review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 2022; 23: 1157‐1172.

- 15. Devries KM, Child JC, Bacchus LJ, et al. Intimate partner violence victimization and alcohol consumption in women: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Addiction 2014; 109: 379‐391.

- 16. Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ, et al. Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Med 2013; 10: e1001439.

- 17. Hegarty KL, Andrews S, Tarzia L. Transforming health settings to address gender‐based violence in Australia. Med J Aust 2022; 217: 159‐166. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/217/3/transforming‐health‐settings‐address‐gender‐based‐violence‐australia

- 18. Devries KM, Mak JY, García‐Moreno C, et al. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science 2013; 340: 1527‐1528.

- 19. Sardinha L, Maheu‐Giroux M, Stöckl H, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. Lancet 2022; 399: 803‐813.

- 20. World Health Organization. Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018. 9 Mar 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256 (viewed May 2024).

- 21. Potter LC, Morris R, Hegarty K, et al. Categories and health impacts of intimate partner violence in the World Health Organization multi‐country study on women's health and domestic violence. Int J Epidemiol 2021; 50: 652‐662.

- 22. Jewkes R, Fulu E, Tabassam Naved R, et al; UN Multi‐country Study on Men and Violence Study Team. Women's and men's reports of past‐year prevalence of intimate partner violence and rape and women's risk factors for intimate partner violence: a multicountry cross‐sectional study in Asia and the Pacific. PLoS Med 2017; 14: e1002381.

- 23. Hegarty K, Sheehan M, Schonfeld C. A multidimensional definition of partner abuse: development and preliminary validation of the composite abuse scale. J Fam Violence 1999; 14: 399‐415.

- 24. Hegarty K, Bush R, Sheehan M. The Composite Abuse Scale: further development and assessment of reliability and validity of a multidimensional partner abuse measure in clinical settings. Violence Vict 2005; 20: 529‐547.

- 25. Ford‐Gilboe M, Wathen CN, Varcoe C, et al. Development of a brief measure of intimate partner violence experiences: the Composite Abuse Scale (Revised)—Short Form. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e012824.

- 26. Loxton D, Powers J, Fitzgerald D, et al. The community composite abuse scale: reliability and validity of a measure of intimate partner violence in a community survey from the ALSWH. J Womens Health Issues Care 2013; 4: 7.

- 27. Rowlands IJ, Holder C, Forder PM, et al. Consistency and inconsistency of young women's reporting of intimate partner violence in a population‐based study. Violence Against Women 2021; 27: 359‐377.

- 28. Moss KM, Loxton D, Mishra G. Does timing matter? Associations between intimate partner violence across the early life course and internalizing and externalizing behavior in children. J Interpers Violence 2023; 38: 10566‐10587.

- 29. Loxton, D, Dolja‐Gore X, Anderson AE, Townsend N. Intimate partner violence adversely impacts health over 16 years and across generations: a longitudinal cohort study. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0178138.

- 30. Brown SJ, Conway LJ, FitzPatrick KM, et al. Physical and mental health of women exposed to intimate partner violence in the 10 years after having their first child: an Australian prospective cohort study of first‐time mothers. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e040891.

- 31. Boxall H, Morgan A. Intimate partner violence during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a survey of women in Australia. Canberra: Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety, 2021. https://www.anrows.org.au/publication/intimate‐partner‐violence‐during‐the‐covid‐19‐pandemic‐a‐survey‐of‐women‐in‐australia (viewed May 2024).

- 32. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Personal safety, Australia, 2021–22. 15 Mar 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime‐and‐justice/personal‐safety‐australia/2021‐22 (viewed May 2024).

- 33. Davies L, Ford‐Gilboe M, Willson A, et al. Patterns of cumulative abuse among female survivors of intimate partner violence links to women's health and socioeconomic status. Violence Against Women 2015; 21: 30‐48.

- 34. Blosnich JR, Bossarte RM. Comparisons of intimate partner violence among partners in same‐sex and opposite‐sex relationships in the United States. Am J Public Health 2009; 99: 2182‐2184.

- 35. Mathews B, Pacella R, Dunne MP, et al. The Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS): protocol for a national survey of the prevalence of child abuse and neglect, associated mental disorders and physical health problems, and burden of disease. BMJ Open 2021; 11: e047074.

- 36. Haslam DM, Lawrence DM, Mathews B, et al. The Australian Child Maltreatment Study (ACMS), a national survey of the prevalence of child maltreatment and its correlates: methodology. Med J Aust 2023; 218 (6 Suppl): S5‐S12. https://www.mja.com.au/system/files/2023‐03/MJA2_v218_is6_Iss2Press_Text.pdf

- 37. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of population and housing: Table Builder Basic, Australia, 2016 (2072.0). 4 July 2017. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2072.0Main%2BFeatures12016?OpenDocument (viewed Oct 2024).

- 38. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS), edition 3, July 2021 ‐ June 2026. 20 July 2021. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/australian‐statistical‐geography‐standard‐asgs‐edition‐3/jul2021‐jun2026 (viewed Apr 2025).

- 39. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Index of Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD). In: Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2021. 27 Apr 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people‐and‐communities/socio‐economic‐indexes‐areas‐seifa‐australia/latest‐release#index‐of‐relative‐socio‐economic‐advantage‐and‐disadvantage‐irsad‐ (viewed Apr 2025).

- 40. Sharma A, Minh Duc NT, Luu Lam Thang T, et al. A consensus‐based checklist for reporting of survey studies (CROSS). J Gen Intern Med 2021; 36: 3179‐3187.

- 41. Swan SC, Gambone LJ, Caldwell JE, et al. A review of research on women's use of violence with male intimate partners. Violence Vict 2008; 23: 201‐314.

- 42. Myhill A. Measuring coercive control: what can we learn from national population surveys? Violence Against Women 2015; 21: 355‐375.

- 43. Yoshihama M, Gillespie BW. Age adjustment and recall bias in the analysis of domestic violence data: methodological improvements through the application of survival analysis methods. J Fam Violence 2002; 17: 199‐221.

- 44. Heise L, Pallitto C, García‐Moreno C, Clark CJ. Measuring psychological abuse by intimate partners: constructing a cross‐cultural indicator for the Sustainable Development Goals. SSM Popul Health 2019; 9: 100377.

Abstract

Objectives: To estimate the prevalence in Australia of intimate partner violence, each intimate partner violence type, and multitype intimate partner violence, overall and by gender, age group, and sexual orientation.

Study design: National survey; Composite Abuse Scale (Revised)—Short Form administered in mobile telephone interviews, as a component of the Australian Child Maltreatment Study.

Setting: Australia, 9 April – 11 October 2021.

Participants: 8503 people aged 16 years or older: 3500 aged 16–24 years and about 1000 each aged 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, or 65 years or older.

Main outcome measures: Proportions of participants who had ever been in an intimate partner relationship since the age of 16 years (overall, and by gender, age group, and sexual orientation) who reported ever experiencing intimate partner physical, sexual, or psychological violence.

Results: Survey data were available for 8503 eligible participants (14% of eligible persons contacted), of whom 7022 had been in intimate relationships. The prevalence of experiencing any intimate partner violence was 44.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 43.3–46.2%); physical violence was reported by 29.1% (95% CI, 27.7–30.4%) of participants, sexual violence by 11.7% (95% CI, 10.8–12.7%), and psychological violence by 41.2% (95% CI, 39.8–42.6%). The prevalence of experiencing intimate partner violence was significantly higher among women (48.4%; 95% CI, 46.3–50.4%) than men (40.4%; 95% CI, 38.3–42.5%); the prevalence of physical, sexual, and psychological violence were also higher for women. The proportion of participants of diverse genders who reported experiencing intimate partner violence was high (62 of 88 participants; 69%; 95% CI, 55–83%). The proportion of non‐heterosexual participants who reported experiencing intimate partner violence (70.2%; 95% CI, 65.7–74.7%) was larger than for those of heterosexual orientation (43.1%; 95% CI, 41.6–44.6%). More women (33.7%; 95% CI, 31.7–35.6%) than men (22.7%; 95% CI, 20.9–24.5%) reported multitype intimate partner violence. Larger proportions of participants aged 25–44 years (51.4%; 95% CI, 48.9–53.9%) or 16–24 years (48.4%, 95% CI, 46.1–50.6%) reported experiencing intimate partner violence than of participants aged 45 years or older (39.9%; 95% CI, 37.9–41.9%).

Conclusions: Intimate partner violence is widespread in Australia. Women are significantly more likely than men to experience any intimate partner violence, each type of violence, and multitype intimate partner violence. A comprehensive national prevention policy is needed, and clinicians should be helped with recognising and responding to intimate partner violence.