Consumer engagement is invaluable for informing, and thus supporting, improvements in the quality of health care delivery by services. Indeed, consumer engagement in health care has become an essential paradigm for Australian policy over the past 20 years, with one of the eight National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards focusing entirely on partnering with consumers.1

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living with kidney disease, several consumer engagement activities were enabled by support from the National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce (NIKTT) and other partners in recent years.2,3,4,5 These consultations allowed communities around the country to provide feedback, opinions, and solutions to kidney care challenges.

Partnering with patients to overcome complex transplantation challenges is crucial and must be done with recognition and acknowledgement of the ways of knowing, being and doing that exist for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.6 For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living with kidney disease and after transplantation, the health system must embed true partnership, engagement and, most importantly, real change from existing verbal feedback that is backed by evidence. Our health systems need to be empowered to embrace, accept and work with (and not against) Indigenous knowledges.7,8,9

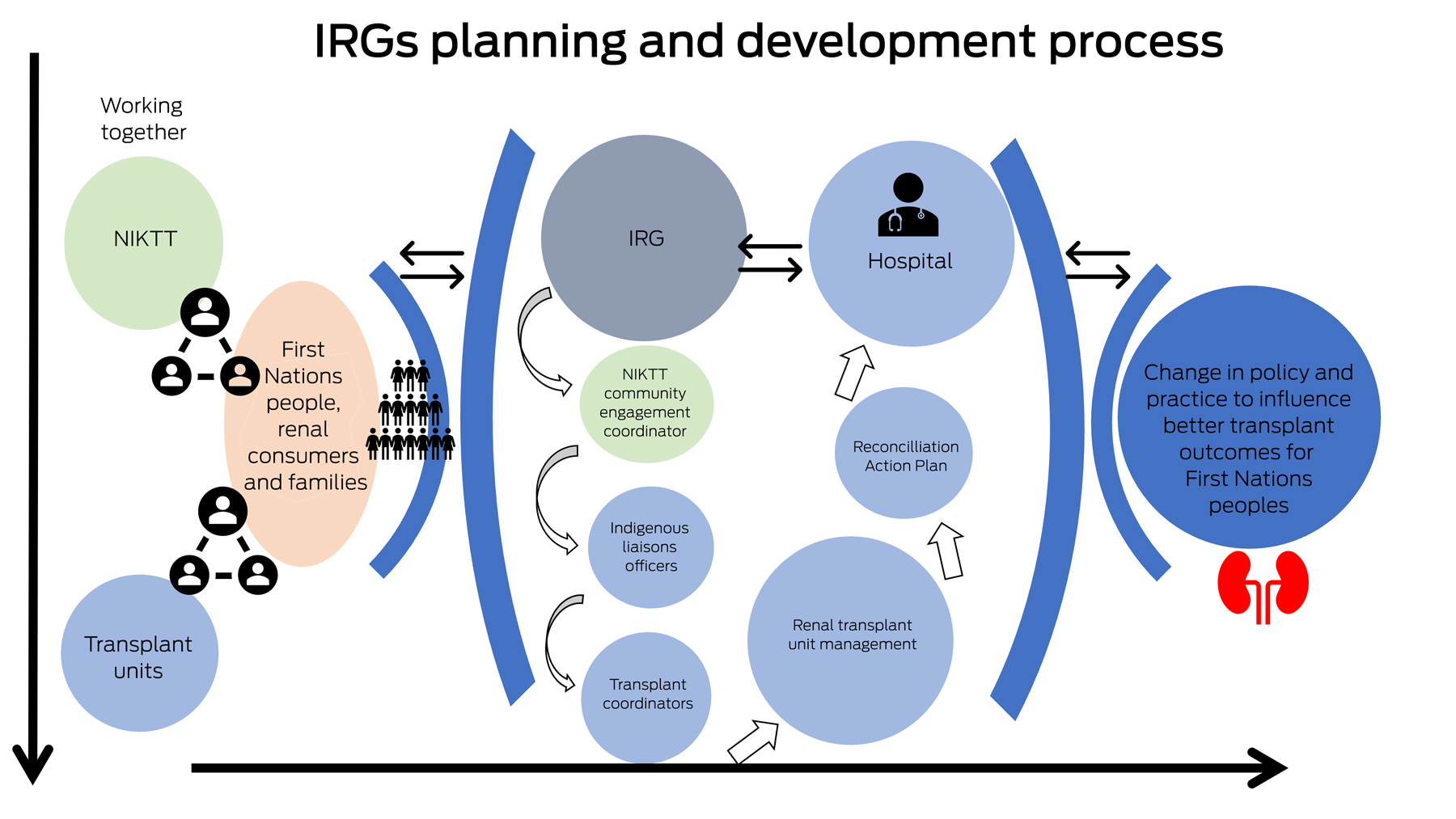

The barriers that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples face when contending with renal services are numerous, as discussed elsewhere in this supplement. The kidney transplant pathway has aptly been described by one Aboriginal patient as “fragmented, confusing, isolating, and burdensome”.10 In order to address some of these barriers, through authentic engagement with consumers, the NIKTT catalysed the establishment of Indigenous Reference Groups (IRGs) within transplantation units around Australia. Five transplantation units were initially selected to host these IRGs — these represented the hospitals that serve the largest proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples on kidney replacement therapy: the Royal Adelaide Hospital (RAH) in South Australia, Princess Alexandra Hospital in Queensland, Westmead Hospital and the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in New South Wales, and Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital in Western Australia.

In this Perspective article, we describe the establishment of the RAH IRG to demonstrate how consumer engagement can deliver effective, culturally safe change.

Doing it right: establishing an effective Indigenous Reference Group in Adelaide

At the RAH, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients come from South Australia, the Northern Territory and western New South Wales to receive kidney transplantation care. This unit therefore provides care to people from many different Nations, each with their own languages, practices and ceremonies, and each with a distinct history of colonisation and health care experiences. These patients and their families travel enormous distances to receive care in a system that was created by, and predominantly for, an English‐speaking, Western‐orientated population. Although located on Kaurna Country, an out‐of‐the‐way wall is the only welcome in Language that consumers coming to the RAH experience.

Due to the complexity of care for patients on kidney replacement therapies, especially those undertaking or having received a transplantation, a specific IRG was established to help patients’ voices systematically report on barriers to care from within the hospital system. To best achieve this, the NIKTT first established a Consumer and Community Engagement (CCE) working group and a dedicated CCE officer role to guarantee consumers were not only consulted but, more importantly, were leading the process of improving access to transplantation. The RAH IRG originally consisted of 20 patients, but as members unfortunately died, membership was subsequently opened to carers and family members.

Seven key design elements (Box 1) for the IRG were developed throughout the establishment of the RAH group. Reflective practices11 were used so that what worked, and what did not work, was continuously discussed and allowed to guide future meetings and partnership growth.

From the experience of establishing this reference group at the RAH, the CCE working group found that specific enablers paved the way for the IRG's successful engagement, integration and activism.

Creating a Blak space

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices were privileged by the creation of a safe, decolonised space through which the IRG could communicate with the clinical world. As no non‐Aboriginal people attended the IRG meetings, the space was seen as a wholly “Blak space”,12 where only Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people were invited to participate, lead and govern meetings. The IRG was positioned as a catalyst to forming trusting relationships between the patients and the hospital staff, as two‐way communication and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander‐led change were actively embraced at a local level.

Reflective practices were employed to ensure meetings were examined and improved upon, a practice that reflects Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing by valuing the acts of deep listening and reflection.12 Questions such as “have the communities’ needs been heard and met?”, “what worked for us and what did not?”, and “how can we do it better next time?” were asked after each IRG meeting. This reflection and real‐time feedback allowed for each meeting to advance and develop based on feedback from within the Blak space.

Engaging clinicians

Clinical support and renal unit “buy‐in” were instrumental in helping to gain traction within the hospital system, specifically formalised first through a letter of support from the head of unit and then through another letter committing to undertake change based on the IRG recommendations. The CCE officer and another member of the IRG formally presented these recommendations to the transplant management meeting in the form of a message stick and a written letter. Without the support of doctors, nurses, coordinators and administrators, the success of the IRG would have been limited: non‐Aboriginal allies throughout the hospital system allowed for doors to be metaphorically opened and lines of communication begun. Box 2 illustrates this process for change and integration.

Leading from within

Aboriginal leads, and strong community connections, allowed for a resilient network to be built and maintained. Having Aboriginal kidney patients drive meeting times, agendas and outputs allowed for powerful momentum within the group to carry its message forward. In addition, having an Aboriginal person lead from within the renal unit was seen as vital to drive the project and maintain momentum.

Early outcomes from the Adelaide Indigenous Reference Group

Real practice change has occurred within the first year of the RAH IRG's existence, due to the strong relationships and trust built between IRG members and clinical staff. These changes include:

- Smoking (organ cleansing) Ceremonies are available on hospital grounds. In June 2022, the first kidney transplant Smoking Ceremony was held to pay respect to the organ donor and their family, while connecting the recipient and organ to the present. By facilitating such ceremonies, the RAH has enabled a holistic view of healing, delivering a more culturally sensitive system of care.13

- A new cultural safety training course is being developed by Aboriginal kidney patients.

- More Aboriginal health practitioners are being employed in the renal unit.

- Non‐Aboriginal staff have expressed gratitude for the opportunity to better understand cultural protocols to facilitate culturally sensitive, and therefore safer, care.

A formal evaluation of this group, and the impact and outcomes it has on the transplantation and renal unit, has been recommended by the CCE and IRG members.

What could hold us back

Although the establishment of the RAH IRG has been successful and provided learnings for NIKTT, there are general challenges for establishing and sustaining IRGs.

Funding

IRGs need financial support for both establishment and continued engagement. Costs are as low as $500 per meeting to cover sitting fees, catering and venue. Secured funding for the sustained support of IRGs is an easy obstacle to overcome once the benefits are considered. As units create new Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander staff positions within kidney teams, more facilitators become available to ensure the cultural safety and continuity of each group.

Powerful partnerships

Although fundamentally enablers, trusting partnerships can also be obstacles if not continuously considered and acted upon. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have experienced innumerable broken promises over the hundreds of years of colonial subjugation. It therefore comes as no surprise that further broken promises or commitments unhonoured lead to frustration, mistrust and, ultimately, lack of engagement from Aboriginal patients.

Taking time

Finally, an important consideration for both the creation of and continued engagement with patient reference groups is time. It takes time to develop the trust and relationships that must occur for IRGs to be effective, and it takes time to implement the cultural considerations of deep listening and reflection. Follow‐up is crucial to this process: anything raised in a meeting, reflected upon after a meeting, or brought up outside of a meeting by members or hospital staff must be recorded and revisited until everyone feels the issue has been managed. These ways of working take up dedicated physical and mental time — a notion that may be antithetical to some hospital processes.

Talking to take action

The benefits of establishing IRGs, from ensuring voices are heard to creating trusting relationships, far outweigh the challenges to implementation. Transplantation units around Australia must prioritise and ensure the sustainable funding of IRGs for them to become embedded within the system. While we continue to grapple with an inequitable health system, new models of care are needed that best serve disparate consumers. Establishing IRGs within hospitals is one important way to enact positive, meaningful and active consumer‐led change.

Box 1 – Essential design elements for the creation of a successful Indigenous Reference Group (IRG)

- Transplantation unit directors and heads of units were consulted before the establishment of the IRG and asked to clearly commit, in writing, to engaging with IRG suggestions on an ongoing basis. This was essential for engaging patients so they could trust that their voices would lead to meaningful change, rather than be sought, collated, and then ignored.

- The Consumer and Community Engagement (CCE) officer identified local clinical leaders and staff in the transplant unit that would be involved with the delivery of care and system change suggested by the IRG, to distinguish advocates and allies.

- The CCE officer used relational networks, clinical patient contacts, and community connections to identify potential IRG members.

- A “Blak space” was created wherein IRG meetings were only led by, and involved only, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This space was deliberately set up to exist both physically and strategically within the transplantation hospital.

- Crucially, a terms of reference document was created that outlined the way in which the IRG worked together and in partnership with the hospital. The IRG then created a list of priorities that provided a positive framework for the unit specifically, and the hospital generally, to improve the cultural safety. These priorities were presented to the head of unit and the transplantation team in the form of a report and a specially commissioned message stick. Meeting minutes were made available to the transplantation team after each meeting.

- All IRG members were compensated for their time and the expertise that they shared.

- Finally, the IRG was brought together every three months using the considerations of time, deep listening, and reflection.

Box 2 – The design and process of the Royal Adelaide Hospital's Indigenous Reference Group (IRG)*

NIKTT = National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce. * This workflow illustrates the ongoing flow of consultation and knowledge exchange allowed both for patients to feel more heard and for clinicians to gain a better understanding of cultural practices and protocols.

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Partnering with Consumers Standard. Sydney: ACSQHC, 2022. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs‐standards/partnering‐consumers‐standard (viewed Dec 2022).

- 2. Hughes JT, Dembski L, Kerrigan V, et al. Gathering perspectives — finding solutions for chronic and end stage kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 2018; 23: 5‐13.

- 3. Duff D, Jesudason S, Howell M, Hughes JT. A partnership approach to engage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with clinical guideline development for chronic kidney disease. Ren Soc Australas J 2018; 14: 84‐88.

- 4. Hughes JT, Freeman N, Beaton B, et al. My experiences with kidney care: a qualitative study of adults in the Northern Territory of Australia living with chronic kidney disease, dialysis and transplantation. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0225722.

- 5. Bateman S, Arnold‐Chamney M, Jesudason S, et al. Real ways of working together: co‐creating meaningful Aboriginal community consultations to advance kidney care. Aust N Z J Public Health 2022; 46: 614‐621.

- 6. Sherwood J, Edwards T. Decolonisation: a critical step for improving Aboriginal health. Contemp Nurse 2006; 22: 178‐190.

- 7. Kirkham R, Maple‐Brown LJ, Freeman N, et al. Incorporating indigenous knowledge in health services: a consumer partnership framework. Public Health 2019; 1; 159‐162.

- 8. Rix L, Rotumah D. Healing mainstream health: Building understanding and respect for Indigenous knowledges. In: Frawley J, Russell G, Sherwood J; editors. Cultural competence and the higher education sector: Australian perspectives, policies and practice. Singapore: Springer Nature, 2020; pp 175‐195.

- 9. Culbong H, Ramirez‐Watkins A, Anderson S, et al. “Ngany Kamam, I speak truly”: first‐person accounts of Aboriginal Youth voices in mental health service reform. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023; 20: 6019.

- 10. Devitt J, Anderson K, Cunningham J, et al. Difficult conversations: Australian Indigenous patients’ views on kidney transplantation. BMC Nephrol 2017; 18: 310.

- 11. Rix EF, Barclay L, Wilson S. Can a white nurse get it? “Reflexive practice” and the non‐Indigenous clinician/researcher working with Aboriginal people. Rural Remote Health 2014; 14: 240‐252.

- 12. Balla P, Jackson K, Quayle AF, et al. “Don't let anybody ever put you down culturally … it's not good …”: creating spaces for Blak women's healing. Am J Community Psychol 2022; 70: 352‐364.

- 13. Central Adelaide Local Health Network. Organ Smoking Ceremony part of healing for recently transplanted patients. Adelaide: CALHN, 2020. https://centraladelaide.health.sa.gov.au/organ‐smoking‐ceremony‐part‐of‐healing‐for‐recently‐transplanted‐patients/ (viewed Aug 2023).

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Adelaide, as part of the Wiley – The University of Adelaide agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Jaqui Hughes was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship (1174758). The Australian Government, represented by the Department of Health and Aged Care, funded the National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce (NIKTT) through an Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme grant. This funding supported the salaries of three of the authors (Kelli Owen, Katie Cundale, and Matilda D'Antoine) and covered the publication fees of this MJA supplement.

We thank the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with kidney disease and transplantation who were involved in the establishment of Indigenous Reference Groups around Australia, as well as their families, carers and communities. We appreciate your dedication to change and your openness to sharing your experiences and visions for the future with us. We acknowledge and appreciate the work and dedication of the consumer engagement working group members, as well as all members of the NIKTT, who contributed to the development and implementation of this work.

No relevant disclosures.