To the Editor: In Australia, gestational diabetes mellitus is diagnosed by 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). The diagnostic criteria are fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥ 5.1 mmol/L, one‐hour glucose level ≥ 10.0 mmol/L, and/or 2‐hour glucose level ≥ 8.5 mmol/L.1,2 International consensus favours OGTT over single measures of glucose because, in the pivotal Hyperglycaemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study, hyperglycaemia at each time point was independently associated with adverse outcomes, individual measures were not well correlated with one another, and no single measure was clearly superior in predicting adverse outcomes, such as birthweight above the 90th percentile, shoulder dystocia and pre‐eclampsia.2,3

To reduce contact time at pathology collection centres during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, measurement of FPG alone has been advocated.4,5 One guideline advised that a result below 4.7 mmol/L may not merit a follow‐up OGTT.4 Another advised diagnosing gestational diabetes mellitus by stand‐alone FPG greater than 5.1 mmol/L.5

To determine the proportion and characteristics of gestational diabetes mellitus cases that would be missed by using alternative criteria, we extracted the results of all obstetrician‐referred OGTTs performed by our private community‐based laboratory between January 2017 and April 2020. The analysis, including determination of Wilson score confidence intervals (CIs), was performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute).

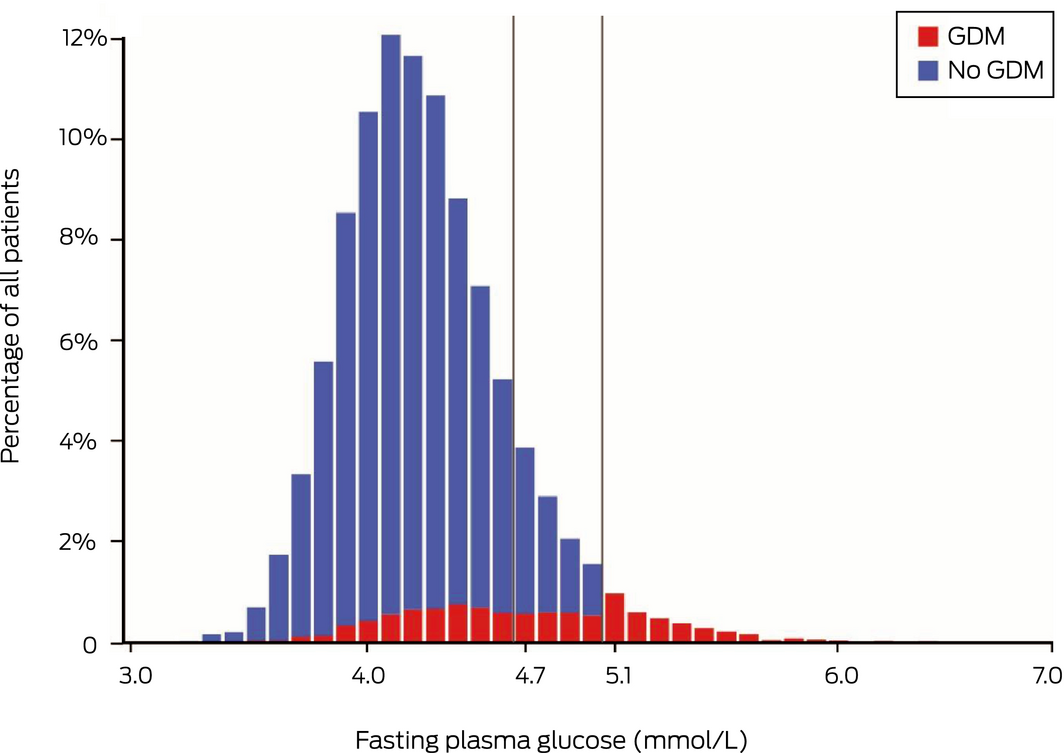

Of 16 169 patients, 1790 (11.1%) were diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus by OGTT. A rule‐out threshold of FPG below 5.1 mmol/L would have resulted in 1202 cases (67%; 95% CI, 65–69%) being missed, and a threshold below 4.7 mmol/L would have resulted in 831 cases (46%; 95% CI, 44–49%) being missed (Box). Women with gestational diabetes mellitus and normal fasting glucose did not have significantly lower one‐ or 2‐hour concentrations than those with increased fasting glucose (data not shown).

Missing the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus exposes women and their newborns to significant risks, including birth weight above the 90th percentile, primary caesarean delivery, neonatal hypoglycaemia, premature delivery, shoulder dystocia or birth injury, intensive neonatal care, hyperbilirubinaemia and pre‐eclampsia. Use of fasting glucose to screen for gestational diabetes mellitus would miss a large proportion of cases, with the potential for significant harm to mothers and their offspring. Clinicians must recognise the substantial limitations of stand‐alone FPG so that pregnant women can be adequately counselled and, if opting out of OGTT, considered for careful monitoring for consequences of undiagnosed gestational diabetes mellitus, such as accelerated growth or polyhydramnios. In regions without significant community spread of COVID‐19, modifying sample collection procedures to ensure strict physical distancing and having dedicated collection centres for vulnerable populations may be better than using deficient diagnostic criteria.

Box – Distribution of fasting glucose results at 24–28 weeks’ gestation in patients with (n = 1790) and without (n = 14 379) gestational diabetes mellitus* (GDM)

The vertical grey lines denote thresholds below which new guidelines propose that oral glucose tolerance testing is not required during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic. * Diagnosed using oral glucose tolerance test.

- 1. Nankervis A, McIntyre HD, Moses R, et al. ADIPS consensus guidelines for the testing and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus in Australia. Sydney: Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society, 2013. http://www.adips.org/downloads/ADIPSConsensusGuidelinesGDM‐03.05.13VersionACCEPTEDFINAL.pdf (viewed Apr 2020).

- 2. International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus Panel. International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 676‐682.

- 3. HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group; Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1991–2002.

- 4. Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society, Australian Diabetes Society, Australian Diabetes Educators Association, Diabetes Australia. Diagnostic testing for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) during the COVID‐19 pandemic: antenatal and postnatal testing advice. https://www.adips.org/documents/RevisedGDMCOVID-19GuidelineFINAL30April2020pdf_000.pdf (viewed June 2020).

- 5. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. COVID‐19 and gestational diabetes screening, diagnosis and management. Melbourne: RANZCOG, 2020. https://ranzcog.edu.au/news/covid-19-and-gestational-diabetes-screening,-diagn (viewed Apr 2020).

No relevant disclosures.