The known: Large amounts of clinical data are collected in electronic health records (eHRs). This information is largely untapped by clinicians for purposes of performance review or professional development.

The new: Health professionals support the use of clinical data for performance feedback and personalised professional development, but believe that EHR data are currently underutilised for these purposes.

The implications: Using routinely collected data for performance review and personalised professional development is a significant opportunity that may improve clinical practice.

The delivery of health care has been transformed by digital technologies,1 particularly by the introduction of electronic health records (eHRs) across all levels of care.2 This is reflected in Australia by the growing interest in digital hospitals; that is, hospitals that employ information management and communications technology to support clinical workflows and to improve safety and quality.3 At the national level, My Health Record will provide an online repository of summary health information for all participating Australians and treating clinicians.4

While the immediate quality and safety benefits for patient care associated with eHR data are increasingly well established,5 the introduction of eHRs has not universally been favourably received.6 Clinicians report that their workloads have increased rather than decreased7 and do not see the benefits outweighing the expense in time and effort involved in gathering electronic health data.8 Only limited clinical data are currently available to clinical teams for informing quality improvement or performance review.9

One area in which the secondary use of data may be of significant value is in reducing clinical variation and improving the alignment of practice with evidence. Many studies have found that a considerable proportion of care delivered in Australia is not evidence‐based and that there is unwarranted variation in care between jurisdictions and services.10

It has long been recognised that personal reflection on clinical practice is a key learning strategy for clinicians.11 This is consistent with evidence that audit and feedback influence behaviour and that educational interventions linked to practice are highly effective.12 However, existing audit and feedback programs are often time‐consuming and expensive, usually involving manual review of health records, which delays feedback.13 In addition, educational interventions are rarely tailored to the individual needs of a clinician or to their performance or scope of practice.14

The increasing volume and quality of data in eHRs may facilitate responsive and personalised educational programs that include audit and feedback components tailored to the individual's practice.15 But surprisingly little research in this area has been published, particularly given the current focus on developing a professional performance framework that more effectively links education with practice in Australia.16 Performance feedback to clinicians is largely restricted to dashboards presenting summary clinical data, with the aim of improving adherence to quality guidelines.17 Few, if any studies have supplied evidence that could guide how data are presented or linked to educational interventions and other activities.

Central to the successful development of systems that employ eHRs or other data sources for delivering targeted education about performance is engaging health professionals in their design.18,19 Accordingly, we explored the attitudes of health professionals, health informaticians, and information communication technology professionals to using eHR data for performance feedback and personalised professional development. The investigation is part of a broader study, Turning Point, that aims to design, implement, and evaluate programs for personalised professional development and performance feedback.

Methods

The study employed a co‐design framework,20 an approach that aims to actively engage end users throughout the project cycle to ensure that the final product meets their needs. Co‐design encourages ownership and support of the methodologies and the solutions developed, leading to increased uptake and sustained implementation of innovations.

We collected information about health professionals’ views on how eHR data should be used for performance feedback and personalised professional development. Co‐design workshops explored whether practitioners currently received data related to their practice; their views on how data could be best presented; what types of data are likely to have the most value; which systems could be developed for presenting data; how these systems could be linked to professional development and training; and barriers to and enablers of using clinical data for educational purposes.

Participants were selected by purposive sampling.21 A mixture of health professional groups were recruited for the workshops, with participants ranging from early career clinicians to experienced health professionals. Participants were assigned to workshops by professional group, and no participant was included in more than one workshop. A total of nine co‐design workshops were held in two major public hospitals in Sydney: three for nursing staff (ten participants in total), three workshops for doctors (15 participants), and one workshop each for information communication technology professionals (six participants), health informaticians (four participants), and allied health professionals (13 participants). A convenience sample was used for the workshops, but we restricted attendance to a maximum of 15 people. Workshops were conducted until data saturation was reached.

Each workshop was facilitated by an interviewer experienced in qualitative research (author TS) with a set of semi‐structured questions. The workshops were audio‐recorded, and one investigator (AJ) made detailed field notes. The interviewer and researcher individually reflected on the content of each focus group meeting, then compared and discussed their reflections, recording any differences in observations in the field notes. The audio recordings were transcribed, de‐identified, and subjected to thematic analysis.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (reference, HREC4953).

Results

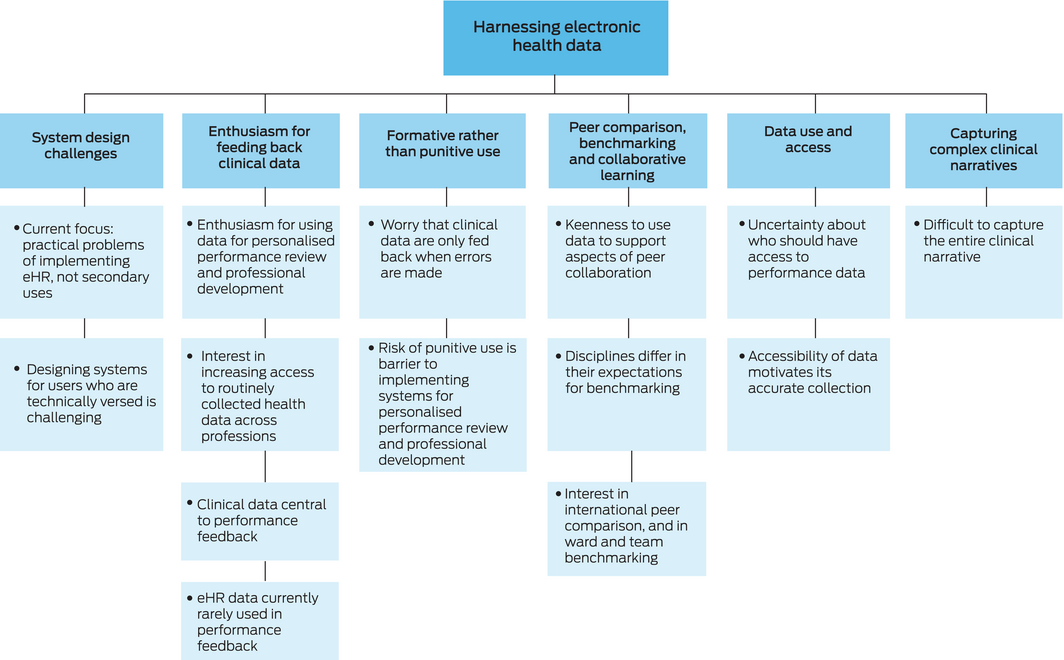

Analysis of workshop transcripts identified six major themes: enthusiasm for feeding back clinical data; formative rather than punitive use; data use and access; capturing complex clinical narratives; peer comparison, benchmarking, and collaborative learning; and system design challenges (Box 1, Box 2).

Enthusiasm for feeding back clinical data

The participants in all workshops were interested in access to routinely collected clinical data for secondary purposes, particularly for performance review and personalised professional development. While several health professionals in the nursing workshop and the three workshops with doctors indicated they had some access to data about their practice and outcomes, most participants felt that it was difficult to access data in eHR systems for secondary purposes, particularly the five early career doctors, who were more frequently unsure about how to access clinical data. Some participants, especially early career doctors, felt that access to data for the purposes of reflection on practice was actively discouraged. A number of more experienced health professionals revealed that they often used performance feedback as the basis for teaching units, but rarely drew data directly from eHRs for this purpose.

Formative rather than punitive use

Participants from all health professions raised concerns about the punitive use of clinical data for identifying their errors. Workshop participants saw such use of performance data as a barrier to implementing any personalised professional development platform. In contrast, participants were excited about using data for instructive purposes, such as identifying the latest evidence or guideline changes, and about rapidly applying this information to clinical practice.

Data use and access

Participants had differing opinions about who should have access to performance data. Doctors in all workshops debated options for access to data by professional colleges, service organisations, government bodies, and clinicians, without reaching a consensus. Medical trainees were clearly worried about the access of professional colleges to information that could affect their career progression. In the workshop for health informaticians, participants suggested that data use was linked to the motivations for collecting and digitising information.

Capturing complex clinical narratives

Participants in all workshops questioned whether clinical data in eHRs captured the complex narratives of clinical practice. Many noted that patients were seen by a team of health care professionals, and that individual eHR data points may not adequately reflect how clinicians performed in certain situations. The difficulty of capturing the complex clinical narrative was considered a barrier to feeding back routinely collected clinical data, especially for professional development, particularly by nurses and allied health professionals.

Peer comparison, benchmarking, and collaborative learning

Participants were keen to use eHR data to support peer collaboration, comparison and benchmarking. All health professional groups saw the potential of eHR data for benchmarking and informing personalised professional development. However, the definition of “benchmarking” differed between disciplines, and the focus of early career doctors was often on individual benchmarking against peers in national and international organisations.

Participants in all workshops expressed interest in using routinely collected data for collaborative and team‐based learning, particularly nurses and allied health professionals, who were more focused on benchmarking of teams and wards than of individuals. They were also more likely to express concerns about making the process competitive, for fear it would lose value.

System design challenges

Participants in all workshops discussed the design of systems for feeding back routinely collected data, particularly information communication technology professionals and informaticians, who noted that health care organisations usually postponed discussing secondary applications, such as exploiting data for professional development, instead giving priority to solving the practical problems of eHR implementation. Participants also commented that it was difficult to exploit health data for secondary purposes without causing negative perceptions of information communication technology staff.

Participants in all workshops noted that systems were generally designed so that they could be used by staff without a high degree of information technology training, with the aim of ensuring that patient safety not be compromised. Designing systems that engage staff with greater technical skills but are still accessible to all was viewed as challenging. One participant suggested the solution was to design systems personalised to individual health professionals.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that health professionals support exploiting clinical data for performance feedback and personalised professional development, and that they believe there is a growing body of data in eHR systems that is underutilised in this respect. This is perhaps unsurprising, given that facilities in many countries, including Australia, are more concerned with implementing or optimising core eHR functions than with investing in secondary opportunities.

Extracting data and reporting performance problems is generally undertaken in the context of quality improvement, and is often related to high level organisational or government performance indicators.22 The data analysed in these programs is often administrative, and not derived from eHRs. Similarly, data analysed in local quality improvement initiatives is usually collected for a defined period of time and not used for professional development purposes.23

There are also significant challenges related to the range of data types collected during routine care delivery in terms of its potential exploitation for secondary purposes such as education. When eHR data are used for providing performance feedback to clinicians, they are usually presented on a static dashboard, rather than in an interactive manner that allows the data to be explored when and how it may be most beneficial for the individual.17 Accompanying the data with scaffolding that assists their interpretation has not been reported, nor has using them to drive programs, such as personalised education.

Our findings provide insights into the barriers to and facilitators of designing programs that support more sophisticated integration of data into interventions aimed at changing the behaviour of health professionals. Unsurprisingly, anxiety about who can access data related to clinical performance and the use of such data for evaluative purposes was a key reservation for participants in all workshops. This is a challenging problem, as managers will feel obliged to react to information about poor performance by clinicians in order to reduce the risk to patient care. It will be difficult for organisations to leave the resolution of identified performance deficits to professional development processes alone, given the effects the problems may have on patient experiences or outcomes of care. These barriers need to be overcome by applying user‐centred design principles and collaboration between clinical professionals and safety and quality regulators for co‐designing such programs. New procedures that enable the secondary use of eHR data should be implemented, including governance structures and tools for rapidly identifying data suitable for performance feedback. Any systems developed will naturally need to comply with local regulations and standards regarding privacy and consent. The types of protection related to disclosure that apply to mortality and morbidity meetings may perhaps be adapted for use in this context.24

The challenges of assessing clinical performance on the basis of eHR data are substantial. They include how to distinguish individual from team performance, and how to gather sufficient information to accurately benchmark performance. Possible approaches to overcoming these problems include initially focusing on team performance and starting with simpler data types, such as antibiotic orders.

Questions of privacy and consent related to the secondary use of data also need to be examined from the perspective of the patient. Legislation regarding the use of patient data for performance feedback and personalised professional development is yet to be developed and agreed upon.

Limitations

This study examined only the views of the health professionals who participated in the workshops. However, a number of workshops, including participants from a range of health disciplines, were conducted, and workshops were conducted until data saturation was reached. Occupation‐based samples were selected to explore topics in depth, and this may have reduced interdisciplinary exchanges of ideas. A further limitation is that the study was conducted at two metropolitan public hospitals; different results may have been reached at rural or private hospitals. Further investigations could be undertaken at a broader range of hospitals, and workshops that included patients and other non‐medical participants could capture their views on the use of their eHR data for the education and professional development of health professionals.

Conclusion

Further investigation and evaluation of the use of eHR data for developing programs that link performance data with behavioural interventions, such as personalised professional development programs, would be useful. This could significantly improve practice and quality care, and support the development of the professional performance framework for linking practice with education that is currently being discussed in Australia.16

Box 2 – Sample quotations from the co‐design workshops, by theme

|

Theme |

Participant |

Sample quotation |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Enthusiasm for feeding back clinical data |

Doctor |

It takes an extraordinary effort to find information out. And in fact, we're not encouraged to do it by medical records department, they don't want us accessing records … when you're not involved directly in their clinical care anymore … well, that's the whole basis of how medical education occurs. [It] is that you do something, and then you find out what happened. |

|||||||||||||

|

Formative rather than punitive use |

Doctor |

If there is a whiff that this is going to be a punitive exercise then we will only put in the minimum required. |

|||||||||||||

|

Doctor |

There's this punitive part of it, you know? We would use that system for different reason. We use that system to improve and the government board may use that system to control us and to check on us. And you know, I think it's just a bit of a conflict of interest and conflict of goals. And if you use the same system for two reasons, and when you have people who can potentially be targeted who contributed to building up all of that base, these people just stop. |

||||||||||||||

|

Data usage and access |

Doctor |

I would be concerned that how I perform in my intern years may affect how a college I want to apply for may see me down the track. |

|||||||||||||

|

Nurse |

The issue for me is all that data's still on paper. So it's nothing to me. I think it needs to be in the computer, people need to sign off on it and they need to own it [their data]. When this data comes out they can say yes, that's what I've done. |

||||||||||||||

|

Capturing complex clinical narratives |

Allied health professional |

People look at data for resource validation. They say, “This is my workload. These are patients I've treated.” And it's very hard to measure Allied Health's value, your fingerprints on a patient are not seen as the patient passes between disciplines, medical nursing, allied surgery, ICU. It's very hard to measure what we do in isolation. |

|||||||||||||

|

Peer comparison, benchmarking and collaborative learning |

Doctor |

I mean how are you performing against the benchmark. And then, you know, you may come from very small hospital, and then you manage every single thing of the night perfectly. And you think, “Oh, I'm so great, I can do everything and la‐dee‐dah.” And then you come to a place like this, and you just don't know what your name is after the night. Because there's so many things happening and you just getting depressed and it's just like, “Oh, I'm so crap, I don't know how to deal with these things.” But if you know what the context is, and how other people are performing, you can kind of have a bit of a better understanding on your performance. |

|||||||||||||

|

Allied health professional |

Can I just make a comment about the tangent to the question you're asking: to describe our weakness, is that we're so varied. And we are siloed within our professions. And so to lift education on an inter‐professional level I think is where we need to be heading. |

||||||||||||||

|

System design challenges |

Health informatician |

The data is there … If you asked someone to reveal this data then there's an obligation to be the police as well as the teacher. And I guess this is one of the problems we've got. |

|||||||||||||

|

Health informatician |

Ideally it would be personalised. So that you can collect the data that you want … I think that's something that would be useful as long as it's able to be done at a personal level. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

- Tim Shaw1,2

- Anna Janssen1

- Roslyn Crampton3,4

- Fenton O'Leary5

- Philip Hoyle6

- Aaron Jones7

- Amith Shetty8

- Naren Gunja3,9

- Angus G Ritchie7,10

- Heiko Spallek11

- Annette Solman12,13

- Judy Kay11

- Meredith AB Makeham1,14

- Paul Harnett3

- 1 Research in Implementation Science and eHealth Group (RISe), University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 2 The Charles Perkins Centre, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 3 Westmead Hospital, Sydney, NSW

- 4 Western Sydney University, Sydney, NSW

- 5 Sydney Children's Hospital Network, Sydney, NSW

- 6 National Centre for Classification in Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 7 Sydney Local Health District, Sydney, NSW

- 8 Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology, Westmead Hospital, Sydney, NSW

- 9 Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 10 Concord Clinical School, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 11 University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 12 Health Education and Training Institute, NSW Health, Sydney, NSW

- 13 Sydney Nursing School, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 14 Australian Digital Health Agency, Sydney, NSW

Tim Shaw serves on the Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) Research Committee and Product Improvement Group. Meredith Makeham is Chief Medical Adviser for the ADHA.

- 1. McGinnis JM, Stuckhardt L, Saunders R, Smith M. Best care at lower cost: the path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington (DC): National Academies Press, 2013. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13444/best-care-at-lower-cost-the-path-to-continuously-learning (viewed July 2018).

- 2. Hillestad R, Bigelow J, Bower A, et al. Can electronic medical record systems transform health care? Potential health benefits, savings, and costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005; 24: 1103–1117.

- 3. Standards Australia. Digital hospitals handbook (SA HB 163:2017). June 2017. Sydney: SAI Global Limited, 2017.

- 4. Australian Digital Health Agency. Australia's national digital health strategy: safe, seamless and secure: evolving health and care to meet the needs of modern Australia. Sydney: ADHA, 2018. https://conversation.digitalhealth.gov.au/australias-national-digital-health-strategy (viewed July 2018).

- 5. Hron JD, Manzi S, Dionne R, et al. Electronic medication reconciliation and medication errors. Int J Qual Health Care 2015; 27: 314–319.

- 6. Mandl KD, Kohane IS. Escaping the EHR trap — the future of health IT. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 2240–2242.

- 7. Bosman RJ. Impact of computerized information systems on workload in operating room and intensive care unit. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2009; 23: 15–26.

- 8. Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. Rand Health Q 2014; 3: 1.

- 9. Robinson TE, Janssen A, Harnett P, et al. Embedding continuous quality improvement processes in multidisciplinary teams in cancer care: exploring the boundaries between quality and implementation science. Aust Health Rev 2017; 41: 291–296.

- 10. Runciman WB, Hunt TD, Hannaford NA, et al. CareTrack: assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia. Med J Aust 2012; 197: 100. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2012/197/2/caretrack-assessing-appropriateness-health-care-delivery-australia

- 11. Schön DA. Educating the reflective practitioner: toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco (CA): Jossey‐Bass, 1987.

- 12. Robinson T, Janssen A, Kirk J, et al. New approaches to continuing medical education: a QStream (spaced education) program for research translation in ovarian cancer. J Cancer Educ 2017; 32: 476–482.

- 13. Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, MacLennan G, et al. Implement Sci 2012; 7: 99.

- 14. Veloski J, Boex JR, Grasberger MJ, et al. Systematic review of the literature on assessment, feedback and physicians’ clinical performance: BEME Guide No. 7. Med Teach 2006; 28: 117–128.

- 15. Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care 2001; 8 Suppl 2: II2–II45.

- 16. Flynn JM. Towards revalidation in Australia: a discussion. Med J Aust. 2017; 206: 7–8. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2017/206/1/towards-revalidation-australia-discussion

- 17. Dowding D, Randell R, Gardner P, et al. Dashboards for improving patient care: review of the literature. Int J Med Inform 2015; 84: 87–100.

- 18. Song M, Spallek H, Polk D, et al. How information systems should support the information needs of general dentists in clinical settings: suggestions from a qualitative study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2010; 10: 7.

- 19. Spallek H, O'Donnell J, Clayton M, et al. Paradigm shift or annoying distraction: emerging implications of web 2.0 for clinical practice. Appl Clin Inform 2010; 1: 96.

- 20. He J, King WR. The role of user participation in information systems development: implications from a meta‐analysis. J Manag Inf Syst 2008; 25: 301–331.

- 21. Quinn Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE, 2002.

- 22. Australian Council on Healthcare Standards. Australasian clinical indicator report. 17th edition 2008–2015. Sydney: ACHS, 2016. https://www.achs.org.au/media/116763/final_acir_-_web_version.pdf (viewed July 2018).

- 23. Langley GJ, Moen RD, Nolan KM, et al. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. San Francisco (CA): Jossey‐Bass, 2009.

- 24. Epstein NE. Morbidity and mortality conferences: their educational role and why we should be there. Surg Neurol Int 2012; 3 (Suppl 5): S377–S388.

Abstract

Objectives: To learn the attitudes of health professionals, health informaticians and information communication technology professionals to using data in electronic health records (eHRs) for performance feedback and professional development.

Design: Qualitative research in a co‐design framework. Health professionals’ perceptions of the accessibility of data in eHRs, and barriers to and enablers of using these data in performance feedback and professional development were explored in co‐design workshops. Audio recordings of the workshops were transcribed, de‐identified, and thematically analysed.

Setting, participants: A total of nine co‐design workshops were held in two major public hospitals in Sydney: three for nursing staff (ten participants), three for doctors (15 participants), and one each for information communication technology professionals (six participants), health informaticians (four participants), and allied health professionals (13 participants).

Main outcome measures: Key themes related to attitudes of participants to the secondary use of eHR data for improving health care practice.

Results: Six themes emerged from the discussions in the workshops: enthusiasm for feeding back clinical data; formative rather than punitive use; peer comparison, benchmarking, and collaborative learning; data access and use; capturing complex clinical narratives; and system design challenges. Barriers to secondary use of eHR data included access to information, measuring performance on the basis of eHR data, and technical questions.

Conclusions: Our findings will inform the development of programs designed to utilise routinely collected eHR data for performance feedback and professional development.