The known Mental health disorders in children and adolescents are common, but their impact on presentations to emergency departments (EDs) is unknown.

The new From 2008–09 to 2014–15, mental health presentations increased by 6.5% per year. Rates of presentation with self-harm or stress-related, mood, and behavioural and emotional disorders increased markedly. The burden on ED resources by presentation was greater for mental health than for physical health presentations.

The implications The number of children presenting to EDs with mental health problems is rising. The reasons should be determined so that mental health care for young people can be improved.

Mental health and substance use disorders are the leading cause of disability in children and young adults worldwide.1 Over a 12-month period, 14% of 4–17-year-olds in Australia — 580 000 children and adolescents — are experiencing mental health problems.2 Mental health disorders during childhood have adverse effects throughout life,3,4 and the onset of 50% of all mental disorders occurs before the age of 14 years.5

Australian children receive mental health care from a variety of community-based organisations,6 but it has been anecdotally reported that an increasing number of children and young people are presenting to emergency departments (EDs) with mental health problems. This is worrying; while EDs are equipped to help children who self-harm or take drug overdoses, they are usually noisy, stimulating environments, not conducive to calming agitated patients.7 Further, patients who require mental health care can disturb the routine and flow of the ED, and can place a greater demand on resources than medical or trauma patients.7 Specialised screening tools and mental health consultants trained in paediatric medicine can reduce the likelihood of hospitalisation and the length of stay in the ED, and also ease security problems,8 but they are not available in all EDs.8,9

Two Australian studies have assessed presentations to EDs by children for mental health problems; both were undertaken more than ten years ago and were single site, cross-sectional studies in tertiary level paediatric EDs. An audit during 2002–03 found that children with psychological emergencies accounted for 0.5% of all presentations over a 10-month period, and that they were more likely to be admitted to hospital than other ED patients.10 A retrospective review in another ED over the same period identified 203 adolescents aged 12–18 years with mental health problems, 47% of whom were admitted to hospital.11 A national study in the United States found that the number of ED visits for mental health problems by children aged 10–14 years increased by 21% during 2006–2011, with a 34% increase for substance-related disorders and a 71% rise for impulse control disorders.12

Mental health problems may place a greater burden on EDs than physical health presentations in terms of triage category, length of stay, proportion meeting the National Emergency Access Target (NEAT) of being admitted or discharged within 4 hours,13 and admission rates. A multi-site study in the US found that paediatric patients with mental health problems were up to three times more likely to be admitted to hospital than patients of the same age with physical problems,14 while another multi-site study found that they were more likely to stay in the ED longer.15

The questions of whether mental health presentations are increasing in number and pose a greater burden than physical health presentations have important policy, service delivery, and workforce training implications. We therefore aimed to document the numbers and proportions of presentations to EDs in Victoria during a 7-year period by patients aged 19 years or younger for mental and physical health problems; the types of mental health diagnoses they received; patient characteristics associated with mental and physical health presentations; and the relative clinical burdens of mental and physical health presentations, including triage category, length of stay, time of presentation, and disposal patterns.

Methods

Data were obtained from the Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset16 (VEMD) for the financial years 2008–09 to 2014–15. The VEMD is a standardised state dataset comprising de-identified demographic, administrative, and clinical data for presentations to Victorian public hospitals with 24-hour EDs. However, diagnostic codes are usually entered by clinicians who have limited training in coding, which can compromise the diagnostic accuracy of the dataset.17

Variables obtained from the VEMD included presentation data (eg, length of stay), departure status (eg, admission), demographic data (eg, age, sex), and diagnosis (full list: online Appendix). Data were collected for children and adolescents aged 0–19 years who presented to general or children’s hospitals; it was assumed that young people with mental health problems would not have visited specialty hospitals (eg, maternity hospitals). Hospital campus data were coded by VEMD as metropolitan or rural in a manner that prevented identification of individual patients.

Statistical analyses

We calculated the absolute number of mental and physical health presentations by children and adolescents to Victorian EDs for each 12-month period. As it was possible that shifts in the age and sex distributions of the general population contributed to changes in ED presentation numbers, we examined annual trends in population growth for Victoria, by VEMD age band and sex, using Australian Bureau of Statistics data for the 7 years assessed.18

Mental health presentations were defined as those leading to an F group diagnosis (F00–F99, Mental and behavioural disorders) according to the International Classification of Diseases, revision 10, Australian modification19 (ICD-10-AM) or a diagnosis of intentional self-harm. As there is no ICD-10-AM diagnostic code for self-harm, we identified these cases by a primary diagnosis of any physical injury together with coding of human intent equal to intentional self-harm. Differences in the numbers of mental and physical health presentations between the first and last years of the study period were expressed as percentages.

We transformed the Statistical Local Area score in the VEMD to a quintile on the Socio-Economic Index for Areas (SEIFA) — Index of Relative Socio-Economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD).20 The IRSAD is an index of economic and social conditions of people and households in an area, based on census data; a lower score corresponds to greater disadvantage.21

We compared patient and presentation characteristics associated with mental and physical health presentations for each financial year. The independence of categorical variables was assessed in χ2 tests. All data were analysed in R 3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Ethics approval

The study was screened and approved by the Royal Children’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee, and was exempted from formal ethics approval. The study was also approved by the Department of Health and Human Services as custodians of the VEMD data.

Results

Over the 7 years, there were 2 763 139 presentations to EDs in Victoria by children aged 0–19 years. We excluded 216 372 records because they did not include a primary diagnosis; 2 546 767 presentations were analysed, of which 52 359 (2.1%) were for mental health problems and 2 494 408 (97.9%) for physical health problems.

The annual number of mental health presentations increased by 46%, from 5988 in 2008–09 to 8726 in 2014–15 (average annual increase, 6.5%). The annual number of physical health presentations grew by 13%, from 336 546 to 381 667 (average annual increase, 2.1%). The proportion of mental health presentations rose from 1.7% in 2008–09 to 2.2% in 2014–15.

Mental health diagnoses

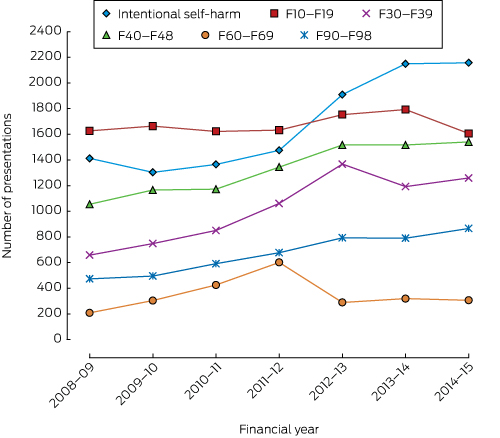

During the 7-year period, 11 770 presentations (22.5% of all mental health presentations) were for intentional self-harm. The number of presentations for intentional self-harm increased by 52.8%, from 1412 in 2008–09 to 2157 in 2014–15, becoming the most frequent mental health-related reason for presentation (Box 1).

Mental health problems related to psychoactive substance use (ICD-10-AM codes F10–F19) comprised the second largest category of presentation (11 694 presentations, 22.3%). Stress and anxiety (ICD-10-AM codes F40–F48), mood disorders (F30–F39), and behavioural and emotional disorders (F90–F98) together accounted for 21 127 presentations (40.3% of mental health presentations). The annual number of presentations for neurotic and stress-related disorders (mainly anxiety) increased by 46.1% during the 7-year period (from 1054 to 1540), for behavioural and emotional disorders (mainly conduct disorder) by 83.1% (from 473 to 866), and for mood disorders (mainly depression) by 91.3% (658 to 1259) (Box 1).

Patient characteristics associated with mental and physical health presentations during 2014–15

In 2014–15, 6709 mental health presentations were by 15–19-year-olds (76.9% of all mental presentations by people aged 0–19 years), and 1617 (18.5%) by 10–14-year-olds. Since 2008–09, the proportion of presentations by 15–19-year-olds for mental health problems had decreased (from 79.7%) while the proportion for 10–14-year-olds had increased (from 14.8%). Most mental health presentations during 2014–15 were by girls (5718, 65.5%), whereas fewer than half of all physical health presentations were by girls (171 625, 45.0%) (Box 2).

The largest proportion of physical health presentations was for children aged 0–4 years (163 966, 43.0% of physical health presentations).

Over the 7-year period, the number of children aged 0–9 years in Victoria increased, but there was only a negligible increase in the older age groups in which the number of mental health presentations had increased (data not shown). The numbers of girls and boys in Victoria each increased by 1.07% per annum over the 7 years, but the proportion of boys who presented to an emergency department with a mental health problem decreased while that of girls increased (Box 2); further, the presentation rates for self-harm, stress-related, mood, and behavioural and emotional disorders each increased markedly over the study period (Box 3).

The proportions of mental and physical health presentations to rural and metropolitan EDs were similar, nor were they influenced by socio-economic status of residence (Box 2). The median time to treatment was slightly lower for children with mental health problems (17 min; interquartile range [IQR], 6–39 min) than for those presenting with physical health problems (21 min; IQR, 9–51 min).

Relative burden of mental and physical health presentations during 2014–15

A greater proportion of mental health presentations (5788 presentations, 66.3%) than of physical health presentations (151 642, 39.7%) were triaged as urgent (triage categories 1–3), and a greater proportion took place after hours (10 pm–2 am: 2167, 24.8% v 47 794, 12.5%; 2 am–8 am: 941, 10.8%; 28 336, 7.4%). Fewer mental than physical health presentations met the NEAT target (5706, 65.4% v 314 585, 82.4%). Children presenting for a mental health problem were more likely to be admitted to hospital than those with physical health problems (2055, 23.6% v 70 614, 18.5%). Similar patterns applied in other years (Box 2).

Discussion

This is the first Australian study to investigate trends in presentations to EDs by children and young adults for mental health problems. The number of children who presented to Victorian public EDs increased between 2008–09 and 2014–15; the number of mental health presentations increased by 46%, that of physical health presentations by 13%. Intentional self-harm and psychoactive substance use were the most frequent reasons for mental health presentations. Stress-related, mood, and behavioural and emotional disorders together accounted for 40% of mental health presentations, and the numbers of presentations for each of these reasons increased rapidly during the 7-year study period. Children who presented with mental health problems were more likely to be triaged as urgent, to present after business hours, to stay longer in the ED, and to be admitted to hospital than those who presented with physical health problems.

Our findings are similar to results reported in the USA, where the number and proportion of mental health visits to EDs by children aged 10–14 years, including those associated with substance use, increased by 21% between 2006 and 2011.12 Earlier studies also found that mental health presentations by children were associated with longer ED stays15 and an increased likelihood of admission to hospital.10,14 In contrast to American studies,14 we found that the number of ED presentations for mood and stress-related disorders, particularly depression and anxiety, rose rapidly. Data from two surveys indicated that the prevalence of major depression in Australia among 4–17-year-olds increased from 2.1% in 1998 to 3.2% in 2013–14,22 but this does not explain the steep rise in presentations to the ED for mood disorders during our study period. We also found that mental health presentations by children aged 10–14 years comprised an increasing proportion of all presentations by children and adolescents, suggesting that community-based care for these children is inadequate.

Our study had several strengths. While other authors have reported the increasing number of children presenting to Victorian EDs,23,24 our data extend this work by differentiating between trends in the relative proportions and burdens of mental and physical health presentations. While there were some changes to ICD-10-AM coding during the study period, their impact would have been minimal; we examined broad diagnostic categories rather than individual diagnoses, and commenced analyses during the 2008–09 financial year, when diagnoses related to depression became available. Coding of diagnoses in VEMD data are not independently verified by third party assessors, but their integrity is regularly assessed by an external advisory group.

Our study was limited by the quality of the VEMD data, particularly by inaccuracies in diagnostic coding, as codes are generally entered by busy clinicians with limited training in coding.17 Data on presentations to private EDs (around 20% of Victorian EDs that receive children25) were not available because private EDs are not required to supply data to the VEMD. In addition, we could not compare the characteristics of presentations to community and paediatric hospitals, as hospital campus coding was applied in the dataset. Investigating these differences is important, as presentation characteristics, hospital resources, and management of paediatric mental health presentations may differ between the two hospital types. Further, the VEMD captures only one diagnosis per presentation, as a result of which some physical health presentations (eg, abdominal pain) by patients with underlying mental health problems (eg, anxiety) were probably excluded from the mental health presentation category. Finally, although attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder is the most common mental health diagnosis in Australian young people,2 the VEMD does not include an ICD-10-AM code for this diagnosis.

Mental health disorders in children and adolescents account for an increasing number of presentations to EDs, with particularly large increases in the numbers of presentations for depression and behavioural problems. In the 2013–14 Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (completed by 6310 caregivers of children aged 4–17 years, 13.9% of whom were assessed as having had a mental disorder during the previous 12 months), 39.6% of those who did not seek help for their children’s mental health problems did not know where to obtain help, while 36.4% were uncertain whether assistance was necessary.22 General practitioners were the most common source of professional help, but they typically referred children to specialist services that often involved out-of-pocket costs that caregivers could not afford. All these factors may delay treatment, resulting in crisis presentations to EDs.

Potential solutions include public health campaigns to improve recognition by caregivers of the symptoms of mental health problems in children and awareness of where to seek help. Providing GPs with skills and financial resources for managing social, emotional and behavioural problems during early childhood is also important. While Headspace provides mental health services for those aged 12–25 years, our data suggest that younger children need more help. Hubs of care for younger children should include clinicians who offer not only co-located services, but also outreach support to the community and schools to share their expertise and, ultimately, to reduce the number of children who present to EDs with mental health problems.

Box 1 – Presentations to Victorian emergency departments by people aged 0–19 years for mental health problems, 2008–09 to 2014–15: the most frequent mental health diagnoses, by ICD-10-AM broad category code

ICD-10-AM = International Classification of Diseases, revision 10, Australian modification. Broad category codes: psychoactive substance use-related (F10–F19), mood disorders (F30–F39), stress- and anxiety-related (F40–F48) adult personality disorders (F60–F69), and behavioural and emotional disorders (F90–F98).

Box 2 – Characteristics of people aged 0–19 years who presented to Victorian emergency departments, 2008–09 to 2014–15, for mental or physical health problems

|

Outcome |

2008–09 |

2010–11 |

2012–13 |

2014–15 |

|||||||||||

|

Mental |

Physical |

P |

Mental |

Physical |

P |

Mental |

Physical |

P |

Mental |

Physical |

P |

||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Presentations (proportion of all presentations) |

5988 |

336 546 |

|

6622 |

347 508 |

|

8503 |

355 722 |

|

8726 |

381 667 |

|

|||

|

Hospital campus (proportion of all presentations) |

|

|

0.14 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

0.004 |

|||

|

Metropolitan |

4048 |

224 465 |

|

4602 |

230 625 |

|

5935 |

239 199 |

|

6239 |

267 386 |

|

|||

|

Rural |

1940 |

112 081 |

|

2020 |

116 883 |

|

2568 |

116 523 |

|

2487 |

114 281 |

|

|||

|

Age band (years) |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|||

|

0–4 |

162 |

138 271 |

|

165 |

144 119 |

|

138 |

148 847 |

|

143 |

163 966 |

|

|||

|

5–9 |

164 |

60 958 |

|

171 |

63 461 |

|

200 |

66 221 |

|

257 |

74 696 |

|

|||

|

10–14 |

888 |

60 662 |

|

1038 |

60 674 |

|

1463 |

61 589 |

|

1617 |

65 528 |

|

|||

|

15–19 |

4774 |

76 655 |

|

5248 |

79 254 |

|

6702 |

79 065 |

|

6709 |

77 477 |

|

|||

|

Sex (boys) |

2285 |

188 427 |

|

2679 |

192 815 |

|

2971 |

195 591 |

|

3008 |

210 042 |

|

|||

|

IRSAD quintile, median (IQR) |

2 |

2 |

|

3 |

2 |

|

3 |

2 |

|

3 |

3 |

|

|||

|

Presentation time |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|||

|

08:00–18:00 (in-hours) |

2060 (34.4%) |

186 392 (55.4%) |

|

2316 (35.0%) |

193 128 (55.6%) |

|

3202 (37.7%) |

196 384 (55.2%) |

|

3468 (39.7%) |

208 241 (54.6%) |

|

|||

|

18:00–22:00 (after hours) |

1431 (23.9%) |

83 489 (24.8%) |

|

1574 (23.8%) |

85 291 (24.5%) |

|

2019 (23.7%) |

89 782 (25.2%) |

|

2150 (24.6%) |

97 296 (25.5%) |

|

|||

|

22:00–02:00 (midnight) |

1660 (27.7%) |

41 630 (12.4%) |

|

1814 (27.4%) |

42 928 (12.4%) |

|

2261 (26.6%) |

43 260 (12.2%) |

|

2167 (24.8%) |

47 794 (12.5%) |

|

|||

|

02:00–08:00 (early morning) |

837 (14.0%) |

25 035 (7.4%) |

|

918 (13.9%) |

26 161 (7.5%) |

|

1021 (12.0%) |

26 296 (7.4%) |

|

941 (10.8%) |

28 336 (7.4%) |

|

|||

|

Triage category |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|||

|

1–3 (potentially to immediately life-threatening) |

3651 (61.0%) |

113 851 (33.8%) |

|

4086 (61.7%) |

124 756 (35.9%) |

|

5444 (64.0%) |

132 514 (37.3%) |

|

5788 (66.3%) |

151 642 (39.7%) |

|

|||

|

4 (potentially serious) or 5 (less urgent) |

2337 (39.0%) |

222 695 (66.2%) |

|

2536 (38.3%) |

222 752 (64.1%) |

|

3059 (36.0%) |

223 208 (62.7%) |

|

2938 (33.7%) |

230 025 (60.3%) |

|

|||

|

Time to treatment (min), median (IQR) |

14 |

24 |

|

18 |

25 |

|

19 |

24 |

|

17 |

21 |

|

|||

|

Length of stay (h) |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|||

|

< 4 |

3698 |

269 350 |

|

3875 |

268 725 |

|

5055 |

278 188 |

|

5706 |

314 585 |

|

|||

|

4–11 |

1959 |

64 060 |

|

2384 |

74 188 |

|

2999 |

72 991 |

|

2623 |

63 069 |

|

|||

|

12–23 |

321 |

3089 |

|

360 |

4550 |

|

443 |

4524 |

|

390 |

4005 |

|

|||

|

> 24 |

10 |

47 |

|

3 |

45 |

|

6 |

19 |

|

7 |

8 |

|

|||

|

Departure status |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|

|

< 0.001 |

|||

|

Return to usual residence |

4688 |

287 256 |

|

5108 |

291 146 |

|

6378 |

292 288 |

|

6199 |

301 681 |

|

|||

|

Ward at this hospital |

984 |

42 842 |

|

1109 |

47 356 |

|

1590 |

53 699 |

|

2055 |

70 614 |

|

|||

|

Transfer to another hospital |

208 |

4115 |

|

255 |

4745 |

|

384 |

4865 |

|

315 |

4390 |

|

|||

|

Departure before treatment complete |

108 |

2333 |

|

147 |

3853 |

|

144 |

4350 |

|

153 |

4447 |

|

|||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

IRSAD = Index of Relative Socio-Economic Advantage and Disadvantage; IQR = interquartile range. Data are shown for only every second financial year for reasons of space. All percentages are column proportions, except rows for “Presentations” and “Hospital campus”. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Population rates of presentations to Victorian emergency departments by people aged 0–19 years with mental health problems, 2008–2015*

|

ICD-10-AM diagnostic category |

Presentations per 10 000 people aged 0–19 years |

||||||||||||||

|

2008–09 |

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Intentional self-harm† |

11 |

10 |

10 |

11 |

14 |

15 |

15 |

||||||||

|

F10–F19 (Psychoactive substance use) |

12 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

13 |

13 |

11 |

||||||||

|

F40–F48 (Neurotic, stress-related) |

8 |

9 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

||||||||

|

F30–F39 (Mood) |

5 |

6 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

8 |

9 |

||||||||

|

F90–F98 (Behavioural/emotional) |

4 |

4 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

||||||||

|

F60–F69 (Adult personality disorders) |

2 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

ICD-10-AM = International Classification of Diseases, revision 10, Australian modification. * Based on number of people in Victoria aged 0–19 years for each financial year.18 † No ICD-10-AM diagnostic category. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 10 May 2017, accepted 12 October 2017

- Harriet Hiscock1

- Rachel J Neely2

- Shaoke Lei1,2

- Gary Freed3

- 1 Health Services Research Unit, Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne, VIC

- 2 Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Melbourne, VIC

- 3 University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States of America

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Erskine HE, Moffitt TE, Copeland WE, et al. A heavy burden on young minds: the global burden of mental and substance use disorders in children and youth. Psychol Med 2015; 45: 1551-1563.

- 2. Lawrence D, Hafekost J, Johnson SE, et al. Key findings from the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2016; 50: 876-886.

- 3. Bor W, Najman JM, O’Callaghan GM, et al. Aggression and the development of delinquent behaviour in children (Trends and Issues in Criminal Justice No. 207). Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, 2001. https://aic.gov.au/publications/tandi/tandi207 (viewed Oct 2017).

- 4. Bosquet M, Egeland B. The development and maintenance of anxiety symptoms from infancy through adolescence in a longitudinal sample. Dev Psychopathol 2006; 18: 517-550.

- 5. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 593-602.

- 6. Johnson SE, Lawrence D, Hafekost J, et al. Service use by Australian children for emotional and behavioural problems: findings from the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2016; 50: 887-898.

- 7. Dolan MA, Fein JA; Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Pediatric and adolescent mental health emergencies in the emergency medical services system. Pediatrics 2011; 127: e1356-e1366.

- 8. Newton AS, Hartling L, Soleimani A, et al. A systematic review of management strategies for children’s mental health care in the emergency department: update on evidence and recommendations for clinical practice and research. Emerg Med J 2017; 34: 376-384.

- 9. Reder S, Quan L. Emergency mental health care for youth in Washington State: qualitative research addressing hospital emergency departments’ identification and referral of youth facing mental health issues. Pediatr Emerg Care 2004; 20: 742-748.

- 10. Starling J, Bridgland K, Rose D. Psychiatric emergencies in children and adolescents: an Emergency Department audit. Australas Psychiatry 2006; 14: 403-407.

- 11. Stewart C, Spicer M, Babl FE. Caring for adolescents with mental health problems: challenges in the emergency department. J Paediatr Child Health 2006; 42: 726-730.

- 12. Torio CM, Encinosa W, Berdahl T, et al. Annual report on health care for children and youth in the United States: national estimates of cost, utilization and expenditures for children with mental health conditions. Acad Pediatr 2015; 15: 19-35.

- 13. Baggoley C, Owler B, Grigg M, et al. Expert panel: review of elective surgery and emergency access targets under the national partnership agreement on improving public hospital services. Report to the Council of Australian Governments. Canberra, 2011. Archived: https://web.archive.org/web/20130511193929/http://www.coag.gov.au/sites/default/files/Expert_Panel_Report%20D0490.pdf (viewed Jan 2018).

- 14. Grupp-Phelan J, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ. Trends in mental health and chronic condition visits by children presenting for care at U.S. emergency departments. Public Health Rep 2007; 122: 55-61.

- 15. Mahajan P, Alpern ER, Grupp-Phelan J, et al. Epidemiology of psychiatric-related visits to emergency departments in a multicenter collaborative research pediatric network. Pediatr Emerg Care 2009; 25: 715-720.

- 16. Department of Health and Human Services (Victoria). Victorian emergency minimum dataset (VEMD). https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/hospitals-and-health-services/data-reporting/health-data-standards-systems/data-collections/vemd (viewed May 2017).

- 17. Spillane IM, Krieser D, Dalton S, et al. Limitations to diagnostic coding accuracy in emergency departments: implications for research and audits of care. Emerg Med Australas 2010; 22: 91-92.

- 18. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3101.0. Australian demographic statistics, Dec 2016. Table 52: estimated resident population by single year of age, Victoria. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/3101.0Dec%202016?OpenDocument (viewed May 2017).

- 19. National Centre for Classification in Health. The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision, Australian modification (ICD-10-AM). Seventh edition. Sydney: NCCH, University of Sydney, 2010.

- 20. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2033.0.55.001. Census of population and housing: Socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2011. Mar 2013. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2033.0.55.001main+features100132011 (viewed May 2017).

- 21. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2033.0.55.001-Census of population and housing: Socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2011. IRSAD. Mar 2013. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2033.0.55.001main+features100042011 (viewed May 2017).

- 22. Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, et al. The mental health of children and adolescents: report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health, 2015. https://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/9DA8CA21306FE6EDCA257E2700016945/%24File/child2.pdf (viewed Oct 2017).

- 23. Freed GL, Gafforini S, Carson N. Age distribution of emergency department presentations in Victoria. Emerg Med Australas 2015; 27: 102-107.

- 24. Lowthian JA, Curtis AJ, Jolley DJ, et al. Demand at the emergency department front door: 10-year trends in presentations. Med J Aust 2012; 196: 128-132. <MJA full text>

- 25. Department of Health and Human Services (Victoria). Victorian hospital lists: Victorian hospital locations by hospital name. https://www.healthcollect.vic.gov.au/HospitalLists/MainHospitalList.aspx (viewed May 2017).

Abstract

Objectives: To identify trends in presentations to Victorian emergency departments (EDs) by children and adolescents for mental and physical health problems; to determine patient characteristics associated with these presentations; to assess the relative clinical burdens of mental and physical health presentations.

Design: Secondary analysis of Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset (VEMD) data.

Participants, setting: Children and young people, 0–19 years, who presented to public EDs in Victoria, 2008–09 to 2014–15.

Main outcome measures: Absolute numbers and proportions of mental and physical health presentations; types of mental health diagnoses; patient and clinical characteristics associated with mental and physical health presentations.

Results: Between 2008–09 and 2014–15, the number of mental health presentations increased by 6.5% per year, that of physical health presentations by 2.1% per year; the proportion of mental health presentations rose from 1.7% to 2.2%. Self-harm accounted for 22.5% of mental health presentations (11 770 presentations) and psychoactive substance use for 22.3% (11 694 presentations); stress-related, mood, and behavioural and emotional disorders together accounted for 40.3% (21 127 presentations). The rates of presentations for self-harm, stress-related, mood, and behavioural and emotional disorders each increased markedly over the study period. Patients presenting with mental health problems were more likely than those with physical health problems to be triaged as urgent (2014–15: 66% v 40%), present outside business hours (36% v 20%), stay longer in the ED (65% v 82% met the National Emergency Access Target), and be admitted to hospital (24% v 18%).

Conclusions: The number of children who presented to Victorian public hospital EDs for mental health problems increased during 2008–2015, particularly for self-harm, depression, and behavioural disorders.