Over the past few decades, there has been interest in the role of music in the operating theatre, both in serious medical research and in the Christmas edition of the MJA.1-4 Music is reportedly played 62–72% of the time in theatre, with classical music being the most popular genre, followed by folk, rock, jazz and blues.5 A number of studies have found beneficial effects of music on surgical performance. For example, Jamaican music and hip-hop (but not classical or jazz music) have been found to increase the speed of robot-assisted laparoscopic surgical tasks, and Jamaican music additionally can lead to more efficient instrument manipulation, suggesting that Bob Marley could be of assistance in surgical settings.6

However, there have also been accounts of dark and dangerous effects of music in operating theatres, with 26% of anaesthetists reporting that music reduced their vigilance,7 and observational studies showing rising levels of frustration and repeat requests between surgical staff in the presence of music.8 Further, a study examining laporoscopic learning performance in novice surgeons found that, on first exposure to performing the laparoscopy, arousing music was associated with poorer task performance and longer task time.9

To date, studies have focused on the impact of music on the surgical skills of real surgeons, while there has been little research into whether music can support surgical skills in the medically untrained general public. Consequently, our study aimed to articulate whether different genres of music can help or hinder speed, accuracy and concentration when undertaking multiorgan resection in the surgical board game Operation. In selecting our music, we decided to focus in particular on classical music by Mozart, well known for its apparent beneficial effects on concentration and intellect (known as the Mozart effect), and rock music from Australia (Oz rock) from the authors’ favourite decade: the 1990s.

Methods

Participants

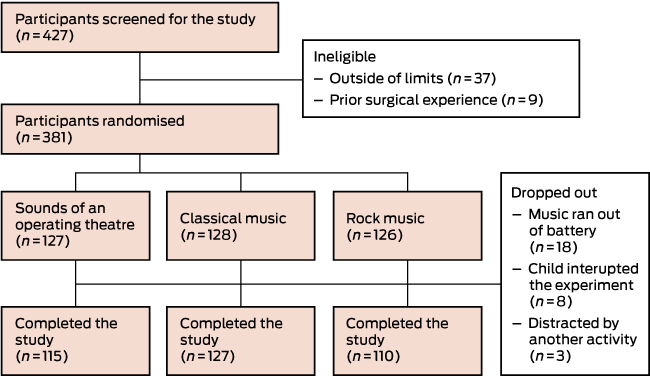

This was a single-blind, three-arm, randomised controlled trial. Aspiring surgeons from the general public aged ≥ 16 years were recruited for the study at the Imperial Festival in May 2016, a public engagement event held annually each spring at Imperial College London that attracts about 15 000 visitors. Participants were excluded if they had any formal surgical training or experience or if they had hearing impairments. In total, 427 participants were screened to take part and 352 completed participation: mean age = 35.0 years (SD, 14.2; range, 16–84 years). Of these, 184 were men (mean age, 34.6 years; SD, 13.8) and 143 were women (mean age, 35.5 years; SD, 14.4) (Box 1).

Procedure

Participants were asked for basic demographic details, including their age, sex, whether they had prior experience of playing the game Operation, and how they rated their hand–eye coordination on a five-point scale (1 = terrible to 5 = excellent). Participants were then randomised using block randomisation to listen through noise-cancelling headphones to one of three things: the sound of an operating theatre (control condition), rock music (“Thunderstruck” from the aptly named album The razor’s edge by Australian rock band AC/DC; tempo, about 134 bpm) or classical music (Andante from Sonata for two pianos, K 448, by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart; tempo, about 60 bpm). Participants were blind as to what they would hear in the headphones, with the nature of the three conditions only revealed to them after they had provided all study data.

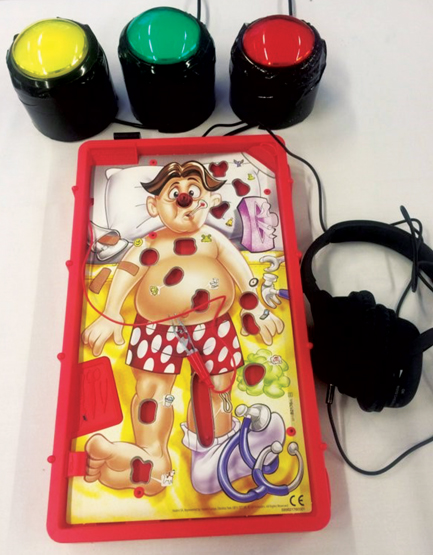

Participants were then given a (very) brief introduction to multiorgan resection techniques and invited to perform the surgery on the patient, Cavity Sam, by removing three plastic pieces from his body in the game Operation (Hasbro; Box 2). Participants were instructed to make as few mistakes as possible in order to increase the chances of Sam’s survival. Immediately after completing the operation participants were asked to rate how much they liked what they had heard on a five-point scale (1 = hated to 5 = loved).

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the length of time taken to complete the operation, with secondary outcome measures of how many mistakes participants made and how distracting they rated the sound in their headphones. Immediately after finishing the operation, participants were asked to rate their perceived level of distraction on a five-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all distracting) to 5 (very distracting). Timing and mistakes were logged through a microcontroller (Arduino) with a serial interface to a graphical user interface (MATLAB; MathWorks). Once the green “Go” button was hit, a real-time clock on the microcontroller was set to increment every 0.1 seconds. Mistakes, where the metal tweezers touched the patient’s body rather than the plastic pieces being removed, made a circuit and triggered the buzzer, and were logged using an analog-to-digital converter connected to the buzzer circuit with an algorithm to ensure that mistakes were only logged once. On finishing, participants pressed the red “Finish” button so that no more mistakes were logged and the current time was recorded. Data were then transmitted over a serial interface to the graphical user interface, where the number of mistakes and time were displayed for data collection. The yellow “Reset” button was pressed to clear the counters before the next participants took part.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were carried out using SPSS Statistics version 23 (IBM). Because research has suggested that men and women like and respond differently to different genres of music,10-12 analyses were performed separately by sex. One-way analyses of variance and χ2 tests were performed to compare differences in baseline between the three aural conditions. Univariate analyses of variance adjusted for age, game experience and hand–eye coordination, and post-hoc tests were used to compare the differences in operating speed, operating mistakes and perceived distraction between the three conditions (operating theatre sounds, rock music and classical music). Sensitivity analyses were also performed, using the same univariate analyses of variance but additionally adjusting for how much people liked the music to explore whether personal preference influenced outcomes.

Ethics approval

Our study received ethics approval from the Conservatoires UK Research Ethics Committee, and all participants provided informed consent prior to participating.

Results

Groups were comparable among the three listening conditions at baseline (Box 3). In addition, there were no differences in age or game experience between men and women (χ2 = 0.759; df = 1; P = 0.384), but there was a marginal difference in self-rated hand–eye coordination (χ2 = 9.661; df = 4; P = 0.047), with women more confident in their abilities than men.

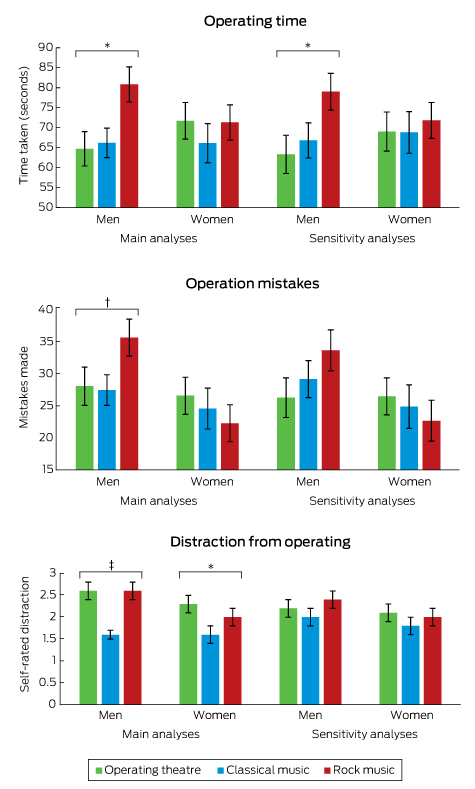

Operating speed

After adjusting for age, game experience and hand–eye coordination, there was a significant difference in operating speed among the conditions in men (F2,181 = 4.236; P = 0.016). Post-hoc tests showed that rock music led to significantly slower operating speed (mean, 80.8 s) than either classical music (mean, 66.2 s; P = 0.012) or the sound of the operating theatre (mean, 64.7 s; P = 0.01). Sensitivity analyses adding how much people liked the music into the model showed comparable results (F2,179 = 3.616; P = 0.029); there was no significant difference between rock music and classical music yet still a significant difference between rock music and the sound of the operating theatre (P = 0.012). In contrast, there was no significant effect on operating speed found for women (Box 4).

Operation mistakes

After adjusting for age, game experience and hand–eye coordination, there was a near-significant difference in the number of operating mistakes made among the conditions in men (F2,173 = 2.575; P = 0.079). Post-hoc tests showed that rock music led to more mistakes (mean, 35.7 mistakes) than classical music (mean, 27.5 mistakes; P = 0.034), with a near-significant difference to the sounds of the operating theatre (mean, 28.1 mistakes; P = 0.068). Sensitivity analyses adding how much people liked the music into the model led to the near-significant effects being attenuated, suggesting that such effects were only found among people who had an aversion to Oz rock. In contrast, there was no significant effect on operation mistakes found for women (Box 4).

Distraction while operating

After adjusting for age, game experience and hand–eye coordination, there was a significant difference in the reported level of distraction for men and women among the conditions (men: F2,182 = 14.757; P < 0.001; women: F2,141 = 3.694; P = 0.027). Post-hoc tests showed that men rated classical music significantly less distracting (mean rating, 1.6/5) than either rock music or the sound of the operating theatre (mean rating for both, 2.6/5; P < 0.001), while women found classical music significantly less distracting (mean rating, 1.6/5) than theatre sounds (mean rating, 2.3/5; P = 0.007) but not rock music (mean rating, 2.0/5). However, sensitivity analyses adding how much people liked the music into the model led to these effects being attenuated in both men and women, suggesting that only people who are partial to the music of Mozart find that it reduces their distraction level and helps them to concentrate (Box 4).

Discussion

This study demonstrates for the first time that rock music, specifically Australian rock music, has detrimental effects on men but not women when pretending to be surgeons, increasing the time taken to “operate” and showing a trend towards more surgical mistakes. In particular, with operating speed, this effect appears to be independent of how much people like rock music. These data are concerning when considering the reported rate of listening to music in operating theatres, the popularity of rock music in these settings, and that men are reportedly more likely to listen to music than women.4 These findings are contrary to the benefits of rhythmic music noted by Siu and colleagues5 and also fly in contrast to opinions expressed by music legends Britney Spears and will.i.am, who believe rock and roll leads to people “going faster, we ain’t going slow-low-low”. However, the findings are in line with those of Miskovic and colleagues,9 as well as those of Conrad and colleagues,13 who found that dichaotic music (auditory stress) was associated with slower task performance among surgeons in a laparoscopic simulator. Thus, one possible explanation for our findings is that the music of AC/DC is perceived by listeners as dichaotic.

Interestingly, this study also demonstrated no improvements in speed or accuracy in either men or women listening to classical music when operating. Although classical music was associated with a lower perceived distraction during the game, this effect was attenuated when factoring in how much people liked the music, with suggestions that only people who are particular fans of Mozart found it beneficial. This lack of improvement in performance when listening to Mozart does not support the so-called Mozart effect, which suggests that Mozart’s compositions can aid spatial task performance.14 However, given that several studies have since thrown doubt onto the claims about the effect, these data are actually in line with general research findings.15

There are some important limitations to this study. The two pieces of music used had different tempi; it therefore remains uncertain whether the genre itself or just the speed of music is responsible for the effects noted. The study was also restricted to just two pieces of music. It is possible that other popular music genres such as electronic music by bands such as Daft Punk might make surgeons “Harder, better, faster, stronger”, a view supported by electro-pop band FM Belfast who claim “We are faster than you”. In addition, caution should be applied when generalising the findings from this study to real-life surgical situations as, despite the genuine tension and feelings of responsibility for the life of Cavity Sam generated by Operation, it cannot be assumed to be a realistic surgical simulation experience, and our participants had no prior surgical training or experience. It is possible that rock music has different effects on the performance of professional surgeons. However, following the advice of progressive rock band La Dispute in their song “The surgeon and the scientist”, we encourage surgeons to consider the findings of this study in their professional practice: “Don’t call this an art project. This is science, this is progress”.

Future research remains to be carried out to explore the full extent of the negative impacts of Australian rock music on medical professionals. For now, caution is advised for those tempted to listen to Oz rock while undertaking high-risk tasks.

Box 2 – Experimental materials, comprising the board game Operation, noise-cancelling headphones, and reset, start and stop buttons for data logging

Box 3 – Mean age, experience of playing Operation, self-rated hand–eye coordination and differences between groups (sound of an operating theatre v classical music v rock music) for men and women

|

Men (n = 184) |

Women (n = 143) |

||||||||||||||

Theatre (n = 55) |

Classical (n = 77) |

Rock (n = 52) |

Test statistic |

P |

Theatre (n = 49) |

Classical (n = 43) |

Rock (n = 51) |

Test statistic |

P |

||||||

Mean age, years (SD) |

35.3 (13.7) |

35.4 (14.8) |

32.6 (12.3) |

F2,181 = 0.77 |

0.47 |

37.3 (15.8) |

35.2 (11.5) |

34.0 (15.3) |

F2,140 = 0.65 |

0.53 |

|||||

Game experience |

50% |

56% |

55% |

χ2 = 0.44; df = 2 |

0.80 |

43% |

53% |

51% |

χ2 = 1.13; df = 2 |

0.57 |

|||||

Mean hand–eye coordination (SD)* |

3.1 (0.9) |

3.1 (0.8) |

3.0 (1.0) |

F2,181 = 0.17 |

0.84 |

3.2 (1.0) |

3.5 (1.0) |

3.2 (0.9) |

F2,140 = 1.24 |

0.29 |

|||||

* Five-point scale (1 = terrible, 5 = excellent). | |||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Mean operating time, operation mistakes and distraction from operating (with standard error) when listening to the sounds of an operating theatre, classical music and rock music

Core analyses adjusted for age, hand–eye coordination and game experience. Sensitivity analyses additionally adjusted for how much people liked the music. Distraction level rated on a five-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all distracting) to 5 (very distracting). * P < 0.05; † P < 0.08 ‡ P < 0.001.

- Daisy Fancourt1,2

- Thomas MW Burton2

- Aaron Williamon1,2

- 1 Centre for Performance Science, Royal College of Music, London, UK

- 2 Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London, UK

We thank George Waddell, Emily Hall, Katey Warran and Dani Doherty for their support with data collection.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Bosanquet DC, Glasbey JC, Chavez R. Making music in the operating theatre. BMJ 2014; 349: g7436.

- 2. Moris DN, Linos D. Music meets surgery: two sides to the art of “healing”. Surg Endosc 2013; 27: 719-723.

- 3. Ardalan ZSM, Vasudevan A, Hew S, et al. The Value of Audio Devices in the Endoscopy Room (VADER) study: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust 2015; 203: 472-475. <MJA full text>

- 4. Allen K, Blascovich J. Effects of music on cardiovascular reactivity among surgeons. JAMA 1994; 272: 882-884.

- 5. Ullmann Y, Fodor L, Schwarzberg I, et al. The sounds of music in the operating room. Injury 2008; 39: 592-597.

- 6. Siu K-C, Suh IH, Mukherjee M, et al. The effect of music on robot-assisted laparoscopic surgical performance. Surg Innov 2010; 17: 306-311.

- 7. Hawksworth C, Asbury AJ, Millar K. Music in theatre: not so harmonious. A survey of attitudes to music played in the operating theatre. Anaesthesia 1997; 52: 79-83.

- 8. Weldon S-M, Korkiakangas T, Bezemer J, Kneebone R. Music and communication in the operating theatre. J Adv Nurs 2015; 71: 2763-2774.

- 9. Miskovic D, Rosenthal R, Zingg U, et al. Randomized controlled trial investigating the effect of music on the virtual reality laparoscopic learning performance of novice surgeons. Surg Endosc 2008; 22: 2416-2420.

- 10. Christenson PG, Peterson JB. Genre and gender in the structure of music preferences. Commun Res 1988; 15: 282-301.

- 11. McNamara L, Ballard ME. Resting arousal, sensation seeking, and music preference. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr 1999; 125: 229.

- 12. Toney GT, Weaver III JB. Effects of gender and gender role self-perceptions on affective reactions to rock music videos. Sex Roles 1994; 30: 567-583.

- 13. Conrad C, Konuk Y, Cao CG, et al. The effect of defined auditory conditions versus mental loading on the laparoscopic motor skill performance of experts. Surg Endosc 2010; 24: 1347-1352.

- 14. Rauscher FH, Shaw GL, Ky CN. Music and spatial task performance. Nature 1993; 365: 611.

- 15. Pietschnig J, Voracek M, Formann AK. Mozart effect–Shmozart effect: a meta-analysis. Intelligence 2010; 38: 314-323.

Abstract

Objective: Over the past few decades there has been interest in the role of music in the operating theatre. However, despite many reported benefits, a number of potentially harmful effects of music have been identified. This study aimed to explore the effects of rock and classical music on surgical speed, accuracy and perceived distraction when performing multiorgan resection in the board game Operation.

Design: Single-blind, three-arm, randomised controlled trial.

Setting: Imperial Festival, London, May 2016.

Participants: Members of the public (n = 352) aged ≥ 16 years with no previous formal surgical training or hearing impairments.

Methods: Participants were randomised to listen through noise-cancelling headphones to either the sound of an operating theatre, rock music or classical music. Participants were then invited to remove three organs from the board game patient, Cavity Sam, using surgical tweezers.

Main outcome measures: Time taken (seconds) to remove three organs from Cavity Sam; the number of mistakes made in performing the surgery; and perceived distraction, rated on a five-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all distracting) to 5 (very distracting).

Results: Rock music impairs the performance of men but not women when undertaking complex surgical procedures in the board game Operation, increasing the time taken to operate and showing a trend towards more surgical mistakes. In addition, classical music was associated with lower perceived distraction during the game, but this effect was attenuated when factoring in how much people liked the music, with suggestions that only people who particularly liked the music of Mozart found it beneficial.

Conclusions: Rock music (specifically Australian rock music) appears to have detrimental effects on surgical performance. Men are advised not to listen to rock music when either operating or playing board games.