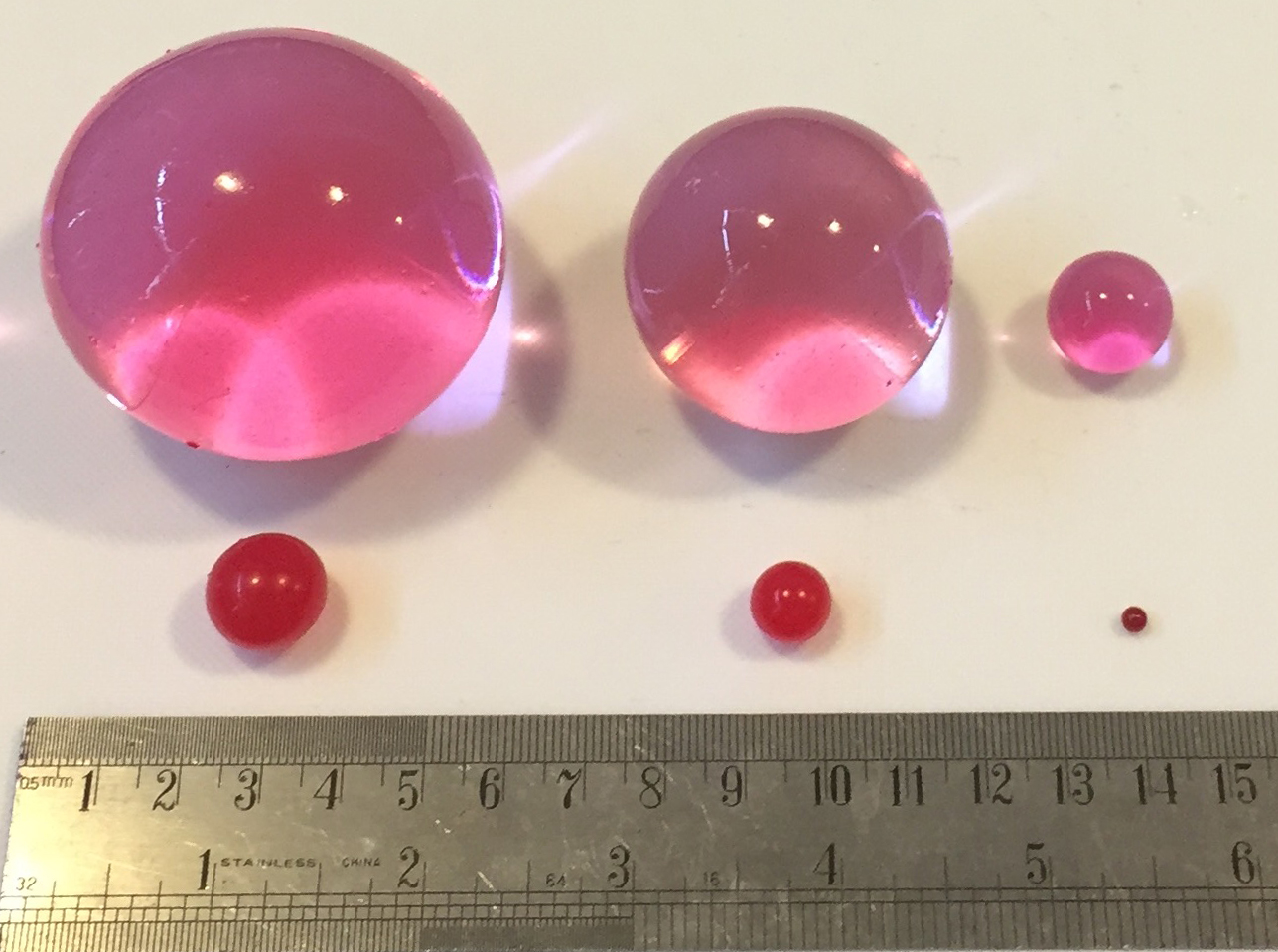

Water-absorbing beads are made from superabsorbent polymer, and can swell to 400 times their original size when immersed in water. They begin as small pellets (1–15 mm) but expand to as much as 6 cm in diameter (Box 1).1,2 Water beads have been marketed for some time for decorative and horticultural purposes, but have recently been promoted as toys (fairy eggs, dragon eggs, jelly beads, water orbs, hydro orbs, polymer beads, gel beads) and as learning aids for autistic children. Due to their progressive expansion after being immersed in fluids, they present a unique foreign body challenge. While most objects that pass the pylorus will also pass through the rest of the gastrointestinal tract, water-absorbing beads that pass the pylorus can later pose an obstruction risk as they swell. There have been reports of serious bowel obstruction (including one death) in children ingesting water beads.1,3,4

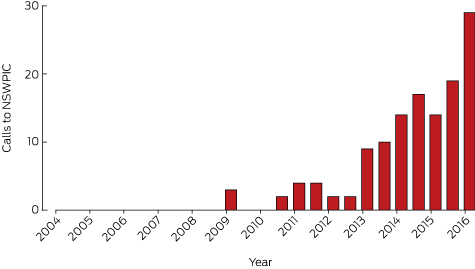

We examined cases reported to the New South Wales Poisons Information Centre (NSWPIC) in which children (0–14 years old) had ingested water beads. The NSWPIC database has been described previously.5 We extracted cases for a 12.5-year period (January 2004 – June 2016) in which “bead” or “ball” was mentioned in the substance field, and then manually reviewed records for inclusion. Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network (reference, LNR/16/SCHN/44).

Since 2004, 129 incidents involving water-absorbing beads were reported to the NSWPIC. Call numbers have increased rapidly in recent years, with 112 exposures (87%) occurring since 2013 (Box 2). Age was recorded in 117 cases; the median was 24 months (interquartile range, 18–48 months). Fifty per cent of the patients (65) were boys, 46% (59) were girls, and sex was not recorded for five cases. Three children were documented as having autism. Most cases were managed at home, with callers advised to watch for signs of obstruction, but 16 calls originated from hospitals, while a further five patients were referred to hospital. Ten children had symptoms suggesting possible obstruction (vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation) that developed between 6 hours and 5 days after ingestion.

Our study indicates that water beads are an emerging foreign body risk to Australian children. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has issued a warning, urging companies not to market water beads as toys, and alerting consumers of the risks.2 While the polymer is non-toxic, it is important for clinicians to recognise the unique challenge posed by these products. They are radiolucent, but other imaging modalities, including ultrasound and computed tomography, are potential options for their detection.1 The NSWPIC does not routinely make follow-up calls, so the outcomes of the cases described here are unknown, but serious complications have been reported in other cases, including water beads lodged in the jejunum1 or distal ileum3 requiring surgical removal. A 6-month-old infant with a jejunal obstruction underwent surgical removal, but developed an anastomotic leak and died of sepsis.4 Patients ingesting multiple or larger sized beads are at increased risk of obstruction, and early hospital referral should be considered. Any patient who has ingested a water bead and has gastrointestinal symptoms should be assessed for potential obstruction.

Received 3 August 2016, accepted 31 August 2016

- 1. Moon JS, Bliss D, Hunter CJ. An unusual case of small bowel obstruction in a child caused by ingestion of water-storing gel beads. J Pediatr Surg 2012; 47: e19-e22.

- 2. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. ACCC warns of dangers of water expanding balls to kids [media release]. 6 Mar 2015. https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/accc-warns-of-dangers-of-water-expanding-balls-to-kids (accessed Jan 2016).

- 3. Zamora IJ, Vu LT, Larimer EL, Olutoye OO. Water-absorbing balls: a “growing” problem. Pediatrics 2012; 130: e1011-e1014.

- 4. Mirza B, Sheikh A. Mortality in a case of crystal gel ball ingestion: an alert for parents. APSP J Case Rep 2012; 3: 6.

- 5. Cairns R, Daniels B, Wood DA, Brett J. ADHD medication overdose and misuse: the NSW Poisons Information Centre experience, 2004–2014. Med J Aust 2016; 204: 154. <MJA full text>

This study was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant (1055176). We also thank staff of the New South Wales Poisons Information Centre.

No relevant disclosures.