Abstract

Objective: Accidental daily dosing of methotrexate can result in life-threatening toxicity. We investigated methotrexate dosing errors reported to the National Coronial Information System (NCIS), the Therapeutic Goods Administration Database of Adverse Event Notifications (TGA DAEN) and Australian Poisons Information Centres (PICs).

Design and setting: A retrospective review of coronial cases in the NCIS (2000–2014), and of reports to the TGA DAEN (2004–2014) and Australian PICs (2004–2015). Cases were included if dosing errors were accidental, with evidence of daily dosing on at least 3 consecutive days.

Main outcome measures: Events per year, dose, consecutive days of methotrexate administration, reasons for the error, clinical features.

Results: Twenty-two deaths linked with methotrexate were identified in the NCIS, including seven cases in which erroneous daily dosing was documented. Methotrexate medication error was listed in ten cases in the DAEN, including two deaths. Australian PIC databases contained 92 cases, with a worrying increase seen during 2014–2015. Reasons for the errors included patient misunderstanding and incorrect packaging of dosette packs by pharmacists. The recorded clinical effects of daily dosage were consistent with those previously reported for methotrexate toxicity.

Conclusion: Dosing errors with methotrexate can be lethal and continue to occur despite a number of safety initiatives in the past decade. Further strategies to reduce these preventable harms need to be implemented and evaluated. Recent suggestions include further changes in packet size, mandatory weekly dosing labelling on packaging, improving education, and including alerts in prescribing and dispensing software.

Methotrexate is a synthetic folic acid analogue used for its antineoplastic and immunomodulating properties. It competitively inhibits folic acid reductase, decreasing tetrahydrofolic acid production and inhibiting DNA synthesis. Low dose methotrexate (administered weekly in doses of 7.5–25 mg) is indicated for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease.1

The unusual dosing schedule of low dose methotrexate is associated with a risk that it will be prescribed, dispensed or administered daily instead of weekly. Used appropriately, methotrexate is considered safe and efficacious; accidental daily dosing, however, can potentially be lethal. Higher or more frequent doses can result in gastro-intestinal mucosal ulceration, hepatotoxicity, myelosuppression, sepsis and death.2 Indeed, there are several literature reports of serious morbidity and mortality linked with methotrexate medication errors.3-7 A study of medication errors reported to the United States Food and Drug Administration over 4 years identified more than 100 methotrexate dosing errors (25 deaths), of which 37% were attributed to the prescriber, 20% to the patient, 19% to dispensing, and 18% to administration by a health care professional.8,9

Current efforts to reduce the likelihood of these errors include the guideline that a specific day of the week for taking methotrexate is nominated.10 Additional care in counselling is recommended to ensure that patients are aware of the dangers of taking extra methotrexate and of signs of methotrexate toxicity.4 In Australia, oral methotrexate is available in packs of 2.5 mg × 30, 10 mg × 15, and 10 mg × 50 tablets. In 2008, the 15-tablet pack was introduced to reduce the risk of toxicity, with the 50-tablet pack being placed on a restricted benefit listing for patients prescribed more than 20 mg per week.

Although overseas data have been published in the form of case reports3,6 and reviews of adverse event databases,9 Australian data on methotrexate medication errors are lacking. In this article, we describe cases of methotrexate medication errors resulting in death reported to the National Coronial Information System (NCIS), summarise reports involving methotrexate documented in the Therapeutic Goods Administration Database of Adverse Event Notifications (TGA DAEN), and describe methotrexate medication errors reported to Australian Poisons Information Centres (PICs).

Methods

This study investigated medication errors recorded in the NCIS, TGA DAEN and PIC datasets. For the purposes of our study, “medication error” was defined as an incident occurring anywhere in the medication process, including prescribing, dispensing or administration. For the error to be included in our study, methotrexate must have been taken by the patient on 3 or more consecutive days.

Data were collected from the NCIS to identify deaths linked with methotrexate medication errors. The NCIS database has a record of reportable deaths from July 2000 onwards for all states except Queensland, for which data are available from January 2001. This database was searched on 4 July 2015 for closed cases from the period 2000–2014, searching for methotrexate in the “cause of death” fields, and by searching for deaths caused by antineoplastic agents in “complications of health care” as “mechanism/object”. A keyword search of attached documentation (findings, autopsy reports) was not performed. Results were manually reviewed for inclusion.

Data were obtained from the open access TGA DAEN for methotrexate adverse events reported from January 2004 to December 2014. Cases coded as “accidental overdose”, “drug administration error”, “drug dispensing error”, “inappropriate schedule of drug administration”, “medication error”, or “overdose” were extracted and manually reviewed for inclusion.

There are four PICs in Australia that together provide around-the-clock poisoning advice to health care professionals and members of the public across Australia. We retrospectively reviewed the New South Wales, Victorian, Western Australian and Queensland PIC databases. South Australia, the Northern Territory, the Australian Capital Territory and Tasmania do not have PICs, but calls from these states are diverted to the New South Wales and Western Australian Poisons Centres. Data from the Victorian PIC were available from May 2005, and from the Queensland PIC from January 2005; other PIC databases were searched for 1 January 2004 onwards, with cases included if they occurred on or before 31 December 2015. Methotrexate cases were manually reviewed for inclusion.

Methotrexate dispensing data from January 2004 to August 2015 were obtained from the Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule Item Reports website (http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/pbs_item.jsp). Item numbers 1622J, 1623K and 2272N were included, corresponding to the oral methotrexate available in Australia. The price of 10 mg × 50 tablets is above the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) co-payment threshold, while those of other pack sizes are below the threshold. The PBS dataset did not capture items under the co-payment threshold until April 2012. Data on the dispensing of 10 mg × 15 and 2.5 mg × 30 tablet packs during the study period is available only for concession card holders; that is, using PBS data for the entire population overestimates the proportion of scripts dispensed for the 10 mg × 50 pack size. As the price of the medicine of interest lies under the co-payment threshold, the study population was restricted to concessional beneficiaries to better reflect use of the medicine.11

We used medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) to describe the data, and performed statistical analyses with Excel (Microsoft) and SPSS 22 (IBM).

Ethics

Ethics approval for the use of NCIS data was granted by the Victorian Justice Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number CF/12/19007); ethics approval for the use of PIC data was granted by the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number LNR-2011-04-06).

Results

We identified 22 instances in the NCIS dataset where methotrexate was listed as a cause of death, including 12 with documented bone marrow suppression. Dosing errors were recorded in seven cases (five men, two women); methotrexate had been taken for between 3 and 10 consecutive days. One further deceased patient took more than the prescribed dose of methotrexate (based on tablets remaining and dispensing date), but was not included because consecutive daily dosing was not conclusively established. Abnormal blood cell counts were documented for all seven deaths linked with dosing errors (median age, 78 years; range, 66–87 years). Reasons for the errors included dosette packaging errors by pharmacists (three cases), prescribing error (one), mistaking methotrexate for another medication (one), dosing error by carer (one), and prescriber–patient miscommunication (one). Causes of death without a documented dosing error included alveolar damage or pulmonary fibrosis (five cases), pneumonia (three), sepsis (three), pancytopenia (one), chronic liver disease (one) and gastro-intestinal haemorrhage (one).

The TGA DAEN included 16 reports of methotrexate-related adverse events meeting our search criteria, including five deaths. These were reviewed for inclusion, and unintended daily dosing was documented in ten cases (median age, 58 years; IQR, 42–74 years; range, 41–85 years; eight women), including two deaths (two women, aged 71 and 83 years).

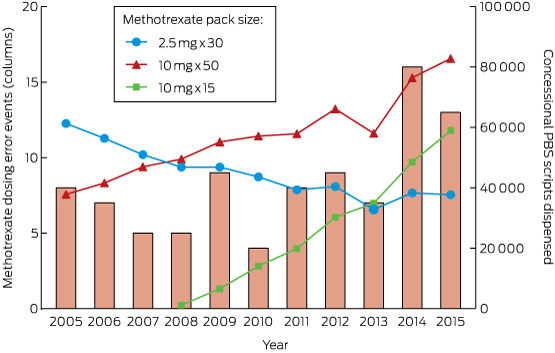

The PIC dataset contained 92 cases of methotrexate-related medication error meeting our inclusion criteria. Between 2005 and 2013, the annual number of events was fairly stable (four to nine cases per year; Box 1). Interestingly, there was an increase during 2014–2015 (16 and 13 cases respectively). We compared PIC exposures with prescribing and dispensing habits, as increased supply might explain an increase in medication errors. The number of methotrexate concessional scripts dispensed during 2005–2015 is shown in Box 1. Most methotrexate was dispensed in 10 mg × 50 tablet packs, the rate of dispensing of which increased steadily during the study period, while that of 2.5 mg tablets had been decreasing. The rate of dispensing of the smaller pack size (10 mg × 15), introduced in 2008, has grown, but has not reached that of the larger pack size, which still accounted for 47% of scripts (and 79% of 10 mg doses) in 2014.

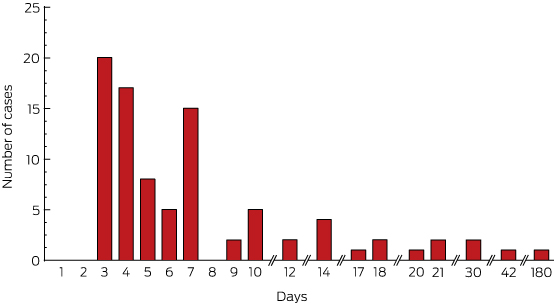

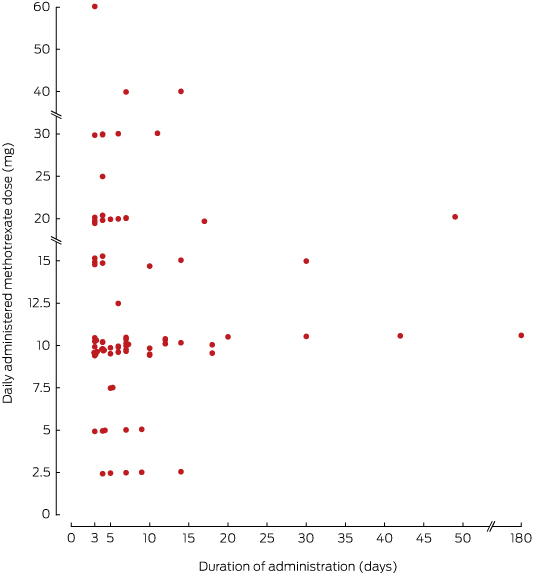

In the PIC dataset, exact ages were recorded in 51% of cases (median age, 65 years; IQR, 52–77 years; range, 28–91 years); at least 18 patients were over 75 years of age. Fifty-five of the 92 patients were women; sex was not recorded in seven cases. Call records documented a range of symptoms, including stomatitis, vomiting, reduced blood cell count and fever. The median number of consecutive days for which methotrexate was taken was 5 (IQR, 4–9 days; range, 3–180 days); the distribution was skewed (Box 2), with 20 cases involving methotrexate taken for 3 consecutive days. The median daily dose taken was 10 mg (IQR, 10–15 mg; range, 2.5–60 mg). Box 3 summarises data on the doses and durations of administration in medication errors reported to PICs.

Where documented, reasons for errors in the PIC dataset included mistaking methotrexate for another medication (11 cases), often folic acid (six cases) or prednisone (four); carer or nursing home error (five); methotrexate being newly prescribed for the patient (five); dosette packing errors by the pharmacy (four); misunderstanding instructions given by the doctor or pharmacist (two); the patient believing it would improve efficacy (two); prescribing error (one); and dispensing or labelling error (one).

There was little overlap in the cases recorded in the three datasets. One DAEN case was a match for one in the NCIS dataset, and there was one possible match of a DAEN case with PIC data. Two of the NCIS deaths were also recorded in PIC databases.

Discussion

This study examined methotrexate dosing errors captured by a range of reporting systems. This included seven deaths in the NCIS dataset (2000–2014), ten cases in the TGA DAEN (including two deaths, 2004–2014) and 92 PIC cases (2004–2015). These datasets had little overlap, with 91 unique reports of methotrexate medication error identified in the three datasets for 2004–2014. Although these events are relatively rare, they can have serious consequences, and all are preventable. Serious toxicity (including death) was noted after as little as 3 consecutive days of methotrexate administration.

This study highlights the benefits of searching both the coronial and TGA datasets, as there was only one case common to these two datasets (with the NCIS capturing more cases than the TGA). Deaths are reported to the coroner according to legislation that defines a “reportable death”, and there is no requirement to report deaths caused by adverse drug events. Indeed, a recent study by our group found that there is little cross-reporting of drug-related deaths by the TGA and the coroner (unpublished data). This raises the question of whether there might be more deaths related to methotrexate dosing errors that are not reported to either body. Similarly, although our PIC dataset includes all Australian poisons calls, not all methotrexate medication errors result in a call to a PIC. Methotrexate medication errors causing toxicity and death may thus be more common than our study suggests.

Further limitations of our study include the delayed release of findings by the coroner. At the time of data extraction, case closure rates for 2013 and 2014 averaged about 75% and 50% respectively. Our study may therefore underestimate the numbers of deaths, especially those occurring during 2013–2014. The TGA dataset documents occasions of methotrexate dosing errors, but the DAEN does not establish causality, so that the deaths recorded in the TGA DAEN represent associations with the medication (rather than causal links). The PIC dataset has limitations, including non-standardised methods for coding calls and the fact that it lacks outcome information (Australian PICs do not routinely conduct follow-up calls). As the PBS dataset did not capture items under the co-payment threshold prior to 2012, we analysed only dispensing data for the concessional population. Although this provides an indication of prescribing trends, it may not be generalisable to the entire population.

The variability in the amount and duration of methotrexate administration prior to a toxic reaction is interesting. The NCIS database showed that taking methotrexate for 3 consecutive days can be fatal, but a small proportion of PIC patients took the drug daily for weeks before they presented to hospital. Such diversity of response could be caused by the marked variability in genes involved in methotrexate absorption, transport, metabolism and excretion.2,12 Variability in renal function and hydration could also affect methotrexate clearance.2 The median age of patients in the NCIS dataset was more than 10 years higher than that in the PIC dataset, suggesting that increased age may be a risk factor for death related to methotrexate dosing errors.

These data revealed a worrying increase in methotrexate medication errors in the PIC dataset for 2014–2015, despite the mentioned efforts to reduce the incidence of these events. It is difficult to explain this increase, but the risk of methotrexate medication error may be increasing as the population ages. Older people may be at increased risk because of a range of problems that includes confusion, memory difficulties, and age-related decline in visual acuity.

This study indicates that ongoing harm is occurring as the result of methotrexate errors. More needs to be done by the manufacturers, the TGA and health professionals to reduce these risks and to improve the harm–benefit balance of weekly methotrexate. One possibility would be to adjust the packaging. A further reduction in pack size may be warranted; for example, each box of the Rheumatrex Dose Pack8 in the United States contains doses for 4 weeks only (similar to the manner in which the weekly dosed bisphosphonates are packaged). Current methotrexate pack sizes in Australia can exceed a year’s supply, depending on the prescribed dose. Although supply of the largest methotrexate pack was changed to a restricted benefit in 2008, this did not result in a reduction in the number of scripts dispensed (Box 1). In addition, uptake of the new, smaller pack has been slow (Box 1). More must therefore be done to discourage prescribing of unnecessarily large quantities of methotrexate.

Further, because it is recommended that folate be co-prescribed with methotrexate, folate and methotrexate could be packaged together in a manner similar to that for oral contraceptives/sugar pills or combination calcium/vitamin D with bisphosphonates. This would be particularly useful given that one of the reasons for methotrexate medication errors we identified was confusion of the medication with folate. The limitations of this approach include the lack of national consensus on the ideal regimen for folate supplementation, with insufficient evidence to justify strongly recommending a specific dose.13 This approach would also require an industry partner to develop such a product,8 and with current prices there may be a limited return on this investment.

Formulating methotrexate as a distinctively coloured tablet could reduce the risks of medication errors by pharmacists, pharmacy technicians and patients; the documented confusion of methotrexate with folic acid tablets is probably related to both being small yellow tablets. Further packaging changes could be made, including clear labelling of the box with a statement such as “Warning: this medicine is usually taken weekly. It can be harmful if taken daily.” Similar labelling changes have been recommended in Australia14 and elsewhere,15 and the results of this study suggest that more needs to be done to mandate sponsors (the companies supplying methotrexate in Australia) to enact these changes.

As some of the dosing error events can be attributed to prescribing or dispensing errors, warnings in prescribing and dispensing software could be improved. Prescribing software could include a pop-up alert when methotrexate is prescribed daily, with the manual entry of an oncological indication needed to override the warning.16 Dispensing software could include alerts if methotrexate is being dispensed too frequently. We identified at least three fatalities caused by daily methotrexate included in pharmacy-filled dosette boxes. Education of pharmacists and their assistants could be improved to increase vigilance and checking of dosette packs containing methotrexate. Further, patients who are prescribed methotrexate for the first time are at particular risk, and extra care in counselling these patients is needed. This includes providing clear verbal and written instructions about dosage.

In conclusion, our study found that methotrexate medication errors, some resulting in death, are still occurring despite a number of safety initiatives. The increase in the number of events during 2014–2015 is particularly concerning. Methotrexate use is likely to continue increasing as Australia’s population ages, so that additional measures are needed to prevent these errors. We have outlined some potential strategies, including altering the packaging, improving education, and including alerts in prescribing and dispensing software.

Box 1 – Methotrexate medication error events reported to Australian Poisons Information Centres, and the quantity of each methotrexate pack size dispensed to concessional patients through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, 2005–2015

Box 2 – Number of consecutive days for which methotrexate was administered in events reported to Australian Poisons Information Centres, 2004–2015*

* Data from the Victorian Poisons Information Centre were available from May 2005, and from the Queensland Poisons Information Centre from January 2005.

Box 3 – Dose and duration of 84 methotrexate medication errors reported to Australian Poisons Information Centres, 2004–2015*

Each point represents a unique event; eight of the 92 reported events are not included because the amount of methotrexate taken each day was ambiguous or not included in the call record. * Data from the Victorian Poisons Information Centre were available from May 2005, and from the Queensland Poisons Information Centre from January 2005.

Received 11 November 2015, accepted 29 February 2016

- Rose Cairns1,2

- Jared A Brown1

- Ann-Maree Lynch3,4

- Jeff Robinson5

- Carol Wylie6

- Nicholas A Buckley1,2

- 1 NSW Poisons Information Centre, The Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW

- 2 University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 3 Western Australian Poisons Information Centre, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth, WA

- 4 University of Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 5 Victorian Poisons Information Centre, Austin Health, Melbourne, VIC

- 6 Queensland Poisons Information Centre, Lady Cilento Children's Hospital, Brisbane, QLD

We thank the staff at the New South Wales, Western Australian, Victorian and Queensland Poisons Information Centres; the Therapeutic Goods Administration; and the National Coronial Information System. We thank Eva Saar (National Coronial Information System) for providing comments on the manuscript. Ongoing toxico-vigilance studies are supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant (1055176).

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Tian H, Cronstein BN. Understanding the mechanisms of action of methotrexate. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 2007; 65: 168-173.

- 2. Schmiegelow K. Advances in individual prediction of methotrexate toxicity: a review. Br J Haematol 2009; 146: 489-503.

- 3. Sinicina I, Mayr B, Mall G, Keil W. Deaths following methotrexate overdoses by medical staff. J Rheumatol 2011; 32: 2009-2011.

- 4. Blinova E, Volling J, Koczmara C, Greenall J. Oral methotrexate: preventing inadvertent daily administration. Can J Hosp Pharm 2008; 61: 275-277.

- 5. Bookstaver PB, Norris L, Rudisill C, et al. Multiple toxic effects of low-dose methotrexate in a patient treated for psoriasis. Am J Heal Pharm 2008; 65: 2117-2121.

- 6. Moisa A, Fritz P, Benz D, Wehner HD. Iatrogenically-related, fatal methotrexate intoxication: a series of four cases. Forensic Sci Int 2006; 156: 154-157.

- 7. Singh YP, Aggarwal A, Misra R, Agarwal V. Low-dose methotrexate-induced pancytopenia. Clin Rheumatol 2007; 26: 84-87.

- 8. Goldsmith P, Roach A. Methods to enhance the safety of methotrexate prescribing. J Clin Pharm Ther 2007; 32: 327-331.

- 9. Moore TJ, Walsh CS, Cohen MR. Reported medication errors associated with methotrexate. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2004; 61: 1380-1384.

- 10. Adverse Drug Reactions Advisory Committee. Methotrexate — name the day. Aust Adv Drug React Bull 1998; 17(2): 3.

- 11. Mellish L, Karanges EA, Litchfield MJ, et al. The Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme data collection: a practical guide for researchers. BMC Res Notes 2015; 8: 634.

- 12. Aslibekyan S, Brown EE, Reynolds RJ, et al. Genetic variants associated with methotrexate efficacy and toxicity in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the treatment of early aggressive rheumatoid arthritis trial. Pharmacogenomics J 2014; 14: 48-53.

- 13. Morgan SL, Baggott JE. Folate supplementation during methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2010; 28 (5 Suppl 61): S102-S109.

- 14. Therapeutic Goods Administration (Australia). Guideline for the labelling of medicines. Aug 2014; p 28. http://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/consult-labelling-medicines-140822-guideline.pdf (accessed Oct 2015).

- 15. National Patient Safety Agency (UK). Towards the safer use of oral methotrexate. London: NPSA, 2004. http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/EasySiteWeb/getresource.axd?AssetID=59985&type=full&servicetype=Attachment (accessed Oct 2015).

- 16. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Severe harm and death associated with errors and drug interactions involving low-dose methotrexate [media release]. 8 Oct 2015. http://www.ismp.org/newsletters/acutecare/showarticle.aspx?id=121 (accessed Oct 2015).

Betty Shuk HanChan

We read with interest regarding a study on “A decade of Australian methotrexate medication errors” and noted there were eight deaths identified as medication errors due to daily dosing. In addition, 92 cases of methotrexate (MTX) dosing errors were reported to the 4 Poisons Information Centres in Australia with the concerning rise in 2014-5. The authors found that low dose daily administration for 3-7 days could cause toxicity and even deaths.1 The toxicity of methotrexate is likely to be more dependent on the duration of exposure rather than serum concentration.(2) In a retrospective series of 28 patients pancytopenia (79%) was found to be the most common manifestation of low dose chronic MTX toxicity.(3) In contrast we observed no effects in acute single dose exposures.(4)

We recently performed an audit of calls referred to the clinical toxicologists at the New South Wales Poisons Information Centres (2004-2015). Ethics approval was granted by the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network HREC (approval number LNR-2011-04-06). There were 21 chronic MTX poisonings, the median age was 62 years (IQR: 52-77), 15 of which were reported to have symptoms indicating toxicity with stomatitis/mucositis (30% 7/21 patients) and neutropenia (30% 7/21 patients) being the most commonly reported symptoms.

Serum MTX concentration (n=20) did not correlate with neutropenia (r=-0.36) or thrombocytopenia (r=0.44).3 There was no difference in MTX concentration between those who died (n=6, 0.05 +/- 0.04 µg/ml) and those that survived (n=14, 0.04 +/- 0.04 µg/ml p=0.45). These concentrations are a many fold lower than those seen with in our audit of asymptomatic acute MTX overdose which had a median concentration of 0.32 +/- 0.08 µg/ml.4 Hence there is no rationale to monitor methotrexate concentrations in chronic methotrexate toxicity; very low concentrations can still be associated with severe or fatal toxicity.

References

1. Cairns R, Brown JA, Lynch AM, Robinson J, Wylie C and Buckley NA. A decade of Australian methotrexate dosing errors. The Medical journal of Australia. 2016;204:384.

2. Goldie JH, Price LA and Harrap KR. Methotrexate toxicity: correlation with duration of administration, plasma levels, dose and excretion pattern. European journal of cancer. 1972;8:409-14.

3. Kivity S, Zafrir Y, Loebstein R, Pauzner R, Mouallem M and Mayan H. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for low dose methotrexate toxicity: a cohort of 28 patients. Autoimmunity reviews. 2014;13:1109-13.

4. Chan BS, Dawson A and Buckley NA. What can toxicologists learn from therapeutic studies about the treatment of acute and chronic methotrexate poisoning? Clinical toxicology. 2016;54 S1:479.

Competing Interests: No relevant disclosures

Dr Betty Shuk HanChan

Prince of Wales Hospital

Carol Simmons

This issue has been recognised for many years now, and numerous measures, such as “naming the day”, have not stopped it.

In 2012, we asked the PBAC to consider restricting the PBS quantities of oral methotrexate for weekly dosing patients (1). The reply we received stated that prescribers are free to prescribe lesser quantities if they wish. Yes, they are, but are unlikely to do so, when a larger pack is available, is potentially more convenient, and the cost per dose to the patient is much less.

Methotrexate supply is clearly a case where medication safety should take priority over economics. Surely it is time to restrict supply of methotrexate to weekly dosing patients to pack sizes consistent with a month’s supply.

(1) Simmons C and Copeland T-S. Your questions to the PBAC. Methotrexate. Aust Prescr 2012;35:46 | 1 April 2012 | http://dx.doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2012.028

Competing Interests: No relevant disclosures

Ms Carol Simmons

Fremantle Hospital, WA