The release of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) has been controversial.1,2 One concern is that the DSM-5 promotes overdiagnosis, encouraging the unnecessary use of medications and potential stigmatisation through diagnostic labelling that does not necessarily lead to better treatment outcomes.3 The lack of consideration for local philosophical, cultural and professional practice needs has also been raised.4 The American Psychiatric Association (APA) should be commended for providing the first thorough revision of the DSM in more than 30 years.5 However, the resulting document is now a more complicated, thicker tome than the original version published in 1952, and literally adds weight to psychiatric diagnosis. A lighter, easier-to-use DSM would be welcomed.

Given the vocal debate that has ensued following the release of DSM-5, the authors of this article feel there is some merit in making the DSM more concise, while still ensuring that the criteria are effective when diagnosing complex cases. It was agreed that revised, more parsimonious DSM criteria were required. The authors were concerned that the APA would already be preparing the DSM-6, and therefore decided to begin with the DSM-(00)7. This paper describes the development of a novel diagnosis (the Bond Adequacy Disorder), new screening criteria (the Bond Additive Descriptors of Anti-Sociality Scale), and our proposed version of the DSM-(00)7.

Methods

James Bond was selected by the authors as a suitable subject on whom to base our study of psychopathology because of his widespread acceptance among both men and women as an aspirational role model, his documented problems with both alcohol and violence,6,7 and the large amount of observational data that was accessible without exceeding our research budget (NZ$80).

Our requests for a diagnostic interview with Commander Bond and for key informant interviews with his colleagues (M, Q and Miss Moneypenny) were turned down (we assume) by MI6 on the grounds that these people were allegedly not known at that address. We were, however, able to gain access to the 50th edition boxset of James Bond video observations.8 This provided more than 45 hours of video records of the subject over a 50-year period (1962–2012), and therefore represented a unique dataset in the history of psychiatry. The observations were not limited to unrepresentative research or clinical settings, but included many opportunities for observing the subject in a range of situations, including settings of considerable stress, intimacy and confrontation, and also in a wide range of cultural settings. This dataset has previously been described in greater detail by other authors on the Amazon.com website.

We also considered the many written observational records prepared by Fleming, Amis, Gardner, Benson and Faulks. However, we found their observations to be surprisingly inconsistent with the video recordings, which we feel must take precedence. The named researchers cannot, unfortunately, be regarded as reliable observers, and seem to have applied journalistic rather than scientific approaches in their work.

In order to catalogue the behaviours exhibited by James Bond, it was agreed that the investigation team would view all 23 Bond video observational records. An initial coding framework was developed, and each observation was reviewed and the behaviours categorised. This methodology was adapted from previously published studies on James Bond; one examined the books to evaluate alcohol consumption,6 another evaluated violence in the films.7

The reviewers were also asked to note any other extreme behaviours that might be suitable for establishing a DSM diagnosis. This included behaviours that are not currently included in the DSM but might be considered criteria for the diagnosis of Bond Adequacy Disorder (BAD: a good diagnosis has at least three words in the title and a catchy acronym).

Each reviewer watched between two and ten movies, depending on the reviewer’s ability to manage what, in some cases, were quite troubling recordings. Because of distress that initial views of the material caused the first author of this article, reviewers were prescribed anxiolytics (of the ethanol class) that they could take on an as-required basis. Eight observations were viewed twice to ensure inclusion of the newly identified criteria, and one recording (“Skyfall”) was viewed in a group setting by five of the reviewers.

The initial categorisations and the newly proposed behaviours were then analysed using a general inductive approach.9 We looked for behavioural themes, and developed an initial list of potentially defining characteristics for BAD. Although we considered using statistical techniques to define behavioural categories, we found that all the behaviours were highly correlated with each other. We therefore used the Delphi method to develop the final criteria for BAD. The initial round of discussions was undertaken by e-mail; when there was significant disagreement over the appropriateness of particular behaviours, the group met to discuss and resolve these questions.

Results

The initial review of the films identified 32 significant behaviours; the list was then refined, identifying 13 key behavioural themes (Box 1).

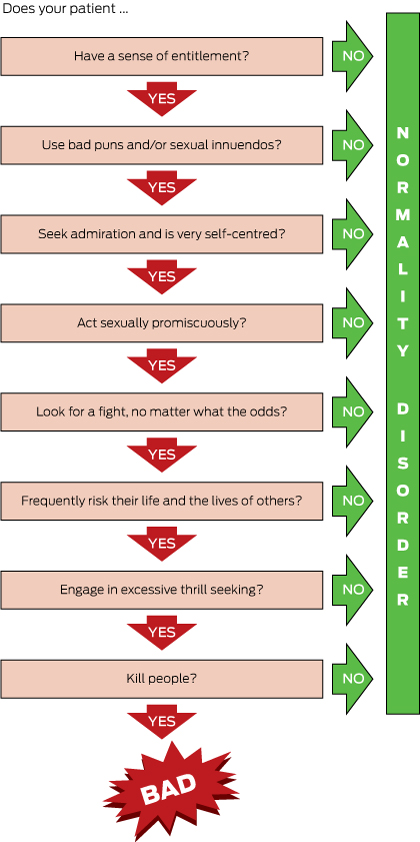

The Delphi process was used to select the eight behaviours that were consistent with a diagnosis of BAD: sense of entitlement, use of bad puns and sexual innuendos, craving for admiration and self-centredness, sexual promiscuity, excessive fighting, taking risks with one’s own life or those of others, excessive thrill seeking, and murder. All eight behaviours must be present for the diagnosis to be confirmed. If the individual presents with further symptoms listed in Box 1, it merely reflects increased severity of the diagnosed disorder.

We elected to further simplify diagnosis by defining just two categories: BAD and Normality Disorder (ie, everyone not meeting the criteria for BAD). The Bond Additive Descriptors of Anti-Sociality Scale (BADASS) tool was created to simplify screening for BAD and Normality Disorder (Box 2).

Discussion

In the resource-limited health settings that many countries face, there is a need to increase efficiencies, including that of diagnostic screening. We have used a novel approach to refine the DSM criteria so that less time need be spent diagnosing patients and more time directed to managing their care appropriately.

It is estimated that a third of the world’s adult population suffers from a mental health disorder.10 This means that efforts to streamline care for mental health would be of benefit for patients, clinicians and health care systems in general. We have used innovative methods to define two diagnostic categories for the DSM-(00)7. There are numerous advantages to this concept, as outlined in Box 3. We cannot see any disadvantages, but nevertheless expect some to be raised in letters to the editor following the publication of our proposal.

Our findings need to be considered in the light of some limitations. The members of our Delphi group had a tendency to be conflict avoiders, so that there was 100% agreement on all questions. It would have been ideal for each observation to have been examined by at least two enthusiastic reviewers. Unfortunately, as several reviewers stated that the movies did not live up to their childhood memories, the idea of recruiting additional reviewers and ruining their childhood spy fantasies seemed cruel and perhaps unethical. It was decided each observation would initially be viewed once, with repeat views only if necessary.

Our research team is not the first to turn to James Bond for insights into personality and emotional states.11-14 The popular media is awash with characters who manifest the personality traits of the dark triad of attributes exhibited by Bond. This triad is complex, comprising subclinical narcissism, psychopathy and Machiavellianism, and is traditionally associated with “bad boys” and antiheroes.13 Bond cold-bloodedly murders with a gun or even with bare hands, and this lack of empathy suggests an underlying psychopathy. His short-term relationships with women involve mate-poaching and manipulation, and his narcissism is manifested by expensive suits, perfect hair, driving expensive cars, and the ability to nonchalantly fix his tie as he walks away from a fatal scuffle or explosion.13 The development of DSM-(00)7 will make identifying and managing these types of individual more straightforward.

While we anticipate gratitude from the APA, we think it unlikely that we will be invited to contribute to the DSM-8. However, our vision for this document is to revive the diagnostic creep of past versions, albeit from the low (two-category) baseline of the DSM-(00)7. Such categories as normality disorder with psychosis, normality disorder with depression, normality disorder not otherwise specified etc would be possible and much more socially acceptable. This will have great appeal for the research community, as they will be able to build research teams (and empires) for receiving large research grants to validate the new diagnostic categories and to invent even more; eg, normality disorder with borderline traits. Our endeavours will also benefit the world of treatment. New medications and psychotherapies will need to be invented and tested to determine whether people can be made supernormal (ie, more normal than normal) or moved from being marginally normal to having a full normality disorder. The old definition of a normal person being someone you don’t know very well will be abandoned, as we will now have criteria for a positive diagnosis of normality disorder, the new normal.

The DSM-4 was followed a few years later by a revised version. To pre-empt this possibility for our new edition, we will publish a revised version of the DSM-(00)7 together with the actual DSM-(00)7. The revised DSM-(00)7 will allow people to make their own diagnosis, and will provide 140 ready-made character tweets (eg, “My BADASS says I have Normality Disorder #gettested #licencetothrill”), quizzes for Facebook, and badges that advertise a BADASS status for dating profiles. We think this will be welcomed by the anti-psychiatry lobby and by regular humans, who will now be able to self-diagnose and self-actualise with the help of the DSM-(00)7. We also believe this will broaden the considerable economic interest in the DSM, and reap even bigger profits than those generated by the DSM-5, as clinicians will feel the pressure to purchase both versions simultaneously. If the projected economic outcomes are not realised, we would be willing to revise the revised edition at a later date. We are interested only in the science of our undertaking, and making mental health understandable for the general public; we will donate any profits to the APA. We expect the APA will incorporate many aspects of the DSM-(00)7 into its later editions, and while credit is always appreciated, a complimentary copy of the DSM-8 is expected.

Areas for future research include reducing the size of other tomes that also keep expanding; for instance, we suggest reducing the size of the dictionary, which is simply too verbose.

Box 1 – A summary of the key behaviours exhibited by James Bond in each of the 23 video observations

Deceit |

Sexual contact |

Risking life (self) |

Risking life (others) |

Attracted to women with unusual names |

Entitled behaviour |

Exploiting others |

Lack of empathy/emotional detachment |

Illegal activity* |

Killing (self-defence and murder) |

Fighting |

Bad puns |

Patronising/sexual innuendo |

|||

Dr. No |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

From Russia with Love |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

Goldfinger |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

Thunderball |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||||

You Only Live Twice |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

Diamonds Are Forever |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

Live and Let Die |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

The Man with the Golden Gun |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

The Spy Who Loved Me |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

Moonraker |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

For Your Eyes Only |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

Octopussy |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

A View to a Kill |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

The Living Daylights |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

Licence to Kill |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

GoldenEye |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

Tomorrow Never Dies |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

The World is Not Enough |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

Die Another Day |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

Casino Royale |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

Quantum of Solace |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

Skyfall |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

*Includes stealing, breaking and entering etc. | |||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Advantages of the DSM-(00)7

Domain |

Advantage |

||||||||||||||

Patient- and caregiver-focused |

There would be little or no stigma attached to a mental health diagnosis. Indeed, we feel the community may wish to embrace their normality disorder: it will be easy, even encouraged, to Google and self-diagnose it.Parents would feel more comfortable about their children’s behaviour probably reflecting normality disorder, so that there would be no need to fret. Those parents who wanted to fret could entertain a diagnosis of BAD for their child. |

||||||||||||||

Clinician-focused |

Diagnosis would be simpler.Clinicians could ignore psychosocial complications.Mental health clinicians would benefit, as their consultations could focus on therapy rather than spending too much time on diagnosis. This will leave them more time to have coffee with their colleagues, helping with their lifelong learning.New categories could be developed for dual diagnosis; eg, normality disorder with psychosis, normality disorder with depression and anxiety. This would have the added benefit of normalising these conditions. |

||||||||||||||

Health care organisations |

Planners would like it, as they would not need to provide as many mental health resources.Insurance billing codes would be simpler and payment quicker. |

||||||||||||||

Commercial entities |

Normality disorder would need treating, so new drugs could be developed to improve the quality of life for those with normality disorder.Big Pharma would appreciate a new diagnostic category being created by someone else for a change. |

||||||||||||||

Other |

It provides a boon to the research community working on projects related to diagnosis and treatment.The concept provides more fodder for editorials about the latest controversies; this will please editors. |

||||||||||||||

- Anna Stowe Alrutz

- Bridget Kool

- Tom Robinson

- Simon Moyes

- Peter Huggard

- Karen Hoare

- Bruce Arroll

- University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Parker G. The DSM-5 classification of mood disorders: Some fallacies and fault lines. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014; 129: 404-409.

- 2. Fawcett J. Reply to Dr. Gordon Parker’s critique of DSM-5 mood disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014; 129: 413-414.

- 3. British Psychological Society. Response to the American Psychiatric Association: DSM-5 development [media release]. Jun 2011. http://apps.bps.org.uk/_publicationfiles/consultation-responses/DSM-5%202011%20-%20BPS%20response.pdf (accessed Sep 2015).

- 4. New Zealand Psychological Society. Position statement on the DSM-5 [media release]. Jan 2014. http://www.psychology.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/NZPsS-Statement-on-the-DSM-FINAL.pdf (accessed Sep 2015).

- 5. Paris J. The intelligent clinician’s guide to the DSM-5. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- 6. Johnson, G, Guha, I, Davis, D. Were James Bond’s drinks shaken because of alcohol induced tremor? BMJ 2013; 347: f7255.

- 7. McAnally, H, Robertson, L Strasburger, V, et al. Bond, James Bond: a review of 46 years of violence in films. JAMA Pediatr 2012; 167: 195-196.

- 8. Bond 50: The complete 23 film collection with Skyfall [DVD]. Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment, 2013.

- 9. Thomas D. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval 2006; 27: 237-246.

- 10. WHO International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Cross-national comparisons of the prevalences and correlates of mental disorders. Bull World Health Organ 2000; 78: 413-426.

- 11. Dalton S. Is James Bond in fact a psycho? The National [internet] 2012; 29 Oct. http://www.thenational.ae/arts-culture/film/is-james-bond-in-fact-a-psycho (accessed Jun 2015).

- 12. Jonason P, Li N, Teicher E. Who is James Bond? The dark triad as an agentic social style. Individ Differ Res 2010; 8: 111-120.

- 13. Jonason P, Webster G, Schmitt D, et al. The antihero in popular culture: life history theory and the dark triad personality traits. Rev Gen Psychol 2012; 16: 192-199.

- 14. Topper J, Schwan S. James Bond in angst? Inferences about protagonists’ emotional states in films. J Media Psychol 2008; 20: 131-140.

Abstract

Objective: To develop a more concise, user-friendly edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The DSM advisory board is probably already hard at work on the DSM-6, so this study is focused on the DSM-(00)7 edition.

Design: We conducted an observational study, using a mixed methods approach to analyse the 50th edition boxset of James Bond experiences. James Bond was selected as a suitably complex subject for the basis of a trial of simplifying the DSM.

Setting: Researchers’ televisions and computers from late January to mid-April in Auckland, New Zealand.

Results: Following a review of the 23 James Bond video observations, we identified 32 extreme behaviours exhibited by the subject; these could be aggregated into 13 key domains. A Delphi process identified a cluster of eight behaviours that comprise the Bond Adequacy Disorder (BAD). A novel screening scale was then developed, the Bond Additive Descriptors of Anti-Sociality Scale (BADASS), with a binary diagnostic outcome, BAD v Normality Disorder. We propose that these new diagnoses be adopted as the foundation of the DSM-(00)7.

Conclusions: The proposed DSM-(00)7 has benefits for both patients and clinicians. Patients will experience reduced stigma, as most individuals will meet the criteria for Normality Disorder. This parsimonious diagnostic approach will also mean clinicians have more time to focus on patient management.