Abstract

Objectives: To investigate medication changes for older patients admitted to hospital and to explore associations between patient characteristics and polypharmacy.

Design: Prospective cohort study.

Participants and setting: Patients aged 70 years or older admitted to general medical units of 11 acute care hospitals in two Australian states between July 2005 and May 2010. All patients were assessed using the interRAI assessment system for acute care.

Main outcome measures: Measures of physical, cognitive and psychosocial functioning; and number of regular prescribed medications categorised into three groups: non-polypharmacy (0–4 drugs), polypharmacy (5–9 drugs) and hyperpolypharmacy (≥ 10 drugs).

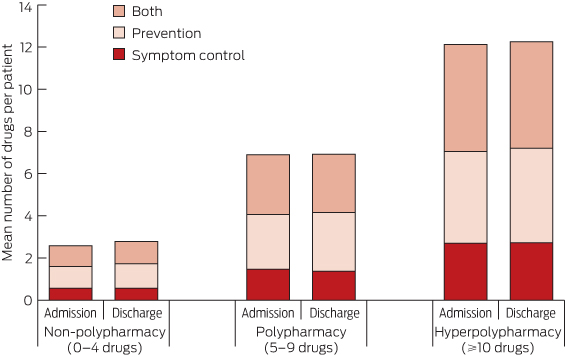

Results: Of 1220 patients who were recruited for the study, medication records at admission were available for 1216. Mean age was 81.3 years (SD, 6.8 years), and 659 patients (54.2%) were women. For the 1187 patients with complete medication records on admission and discharge, there was a small but statistically significant increase in mean number of regular medications per day between admission and discharge (7.1 v 7.6), while the prevalence of medications such as statins (459 [38.7%] v 457 [38.5%] patients), opioid analgesics (155 [13.1%] v 166 [14.0%] patients), antipsychotics (59 [5.0%] v 65 [5.5%] patients) and benzodiazepines (122 [10.3%] v 135 [11.4%] patients) did not change significantly. Being in a higher polypharmacy category was significantly associated with increase in comorbidities (odds ratio [OR], 1.27; 95% CI, 1.20–1.34), presence of pain (OR, 1.31; 1.05–1.64), dyspnoea (OR, 1.64; 1.30–2.07) and dependence in terms of instrumental activities of daily living (OR, 1.70; 1.20–2.41). Hyperpolypharmacy was observed in 290/1216 patients (23.8%) at admission and 336/1187 patients (28.3%) on discharge, and the proportion of preventive medication in the hyperpolypharmacy category at both points in time remained high (1209/3371 [35.9%] at admission v 1508/4117 [36.6%] at discharge).

Conclusions: Polypharmacy is common among older people admitted to general medical units of Australian hospitals, with no clinically meaningful change to the number or classification (symptom control, prevention or both) of drugs made by treating physicians.

Research has confirmed a significant association between polypharmacy — defined here as five or more regular prescription medications1 — and adverse outcomes among older people living in the community. The associations of polypharmacy in older people admitted to hospital have been less extensively explored. Older inpatients are a vulnerable group, at high risk of prolonged hospital stays, institutionalisation and death.2 Several studies have reported a high prevalence of potentially inappropriate medications among older inpatients (ranging from 20%3 to 60%4) and, while potentially inappropriate medications have been linked to adverse drug reactions,5 the most significant predictor of adverse drug reactions among inpatients is the number of medications prescribed.6

Medications can, of course, prolong life and prevent serious morbid events in older people. People aged 80 years and over are at highest risk of cardiovascular events, and the absolute benefits of primary and secondary prevention may be greatest in this group.7 Medications can also improve quality of life through symptom control and maintenance of function. Individualisation of therapy should underpin prescribing, weighing up the potential benefits and risks of medication with reference to the patient's own goals of care.8,9 Hospitalisation presents an opportunity for physicians to undertake such a process and to rationalise prescribing for older people.

We aimed to investigate medication changes for older inpatients and explore patient characteristics associated with polypharmacy.

Methods

Participants and setting

This prospective cohort study included patients aged 70 years or older admitted to general medical units of 11 acute care hospitals in Queensland and Victoria — two small secondary care centres (120–160 beds), two rural hospitals (250–280 beds), four metropolitan teaching facilities (300–450 beds) and three major tertiary referral centres (> 650 beds).

Recruitment took place between July 2005 and May 2010 as part of three cohort studies, described in detail elsewhere.10-12 Personal or proxy patient consent was obtained in writing before patients entered the study. Patients were excluded if they were admitted to coronary or intensive care units, received palliative care only, or were transferred out of general medical units within 24 hours of admission to inpatient wards. Recruitment took place on weekdays only.

Measurement tool and outcome measures

The interRAI assessment system for acute care (interRAI AC)13 was used for data collection. This instrument screens many domains, including cognition, communication, mood, behaviour, activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), continence, nutrition, skin condition, falls and medical diagnosis.14 IADL items represent a higher order of functioning than the basic ADL items and dependence in IADL items is likely to occur before dependence in ADL. The interRAI AC was specifically developed for use in the acute care setting, to support comprehensive geriatric assessment of older inpatients.14

Trained nurse assessors gathered data about the patient's physical, cognitive and psychosocial functioning in the premorbid period (before the current episode of illness, assessed retrospectively at admission) and at admission (based on observations of patients during their first 24 hours in the ward). All available sources of information, including the patients, carers and the medical, nursing and allied health staff, were utilised to complete the interRAI AC instrument, either directly as verbal reports or indirectly through written entries in hospital records.

There are scales embedded in the interRAI instruments that combine single items belonging to a domain (eg, ADL, IADL and cognition), which are used to describe the presence and extent of deficits in that domain.15 Here, the short ADL scale, the IADL performance scale and the cognitive performance scale were used as summary measures of functional and cognitive status, with higher scores indicating greater incapacity.15

For all patients, prescribed medications were recorded about 24 hours into their hospital stay and again at discharge from hospital. These lists were reviewed so that medications used for a finite period in hospital to manage acute medical conditions (eg, intravenous antibiotics, diuretics and subcutaneous anticoagulants) were not included in the number of regular prescribed medications. Complementary and as-required medications were also excluded. The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system codes, plus doses, routes of administration and dosing regimens, were recorded at admission and discharge. Data were entered by pharmacists or pharmacy students and verified by a second pharmacist or a geriatrician. Medications were classified as being for controlling symptoms, prevention or both, based on principles used in palliative care settings,16,17 as well as expert opinion and consensus among us (geriatricians, physicians and clinical pharmacologists).

Analysis

Frequency distributions were used to describe the characteristics of the study population. Polypharmacy status was categorised into three groups: non-polypharmacy (0–4 drugs), polypharmacy (5–9 drugs) and hyperpolypharmacy (≥ 10 drugs).18

Depending on the distribution of the data, non-parametric (Kruskal–Wallis test) or parametric (analysis of variance) methods were used to compare continuous data across the polypharmacy categories. For categorical variables, χ2 tests were used. For paired data, the paired t-test (continuous data) or the McNemar test (nominal data) was used to examine changes between admission and discharge. A variation of the McNemar test (McNemar–Bowker test of symmetry) was used when there were more than two categories.

To examine whether the factors that were significant in univariate analysis were independently associated with the dependent variable (polypharmacy status measured at the ordinal level), an ordinal regression proportional odds procedure was used. Tests for multicollinearity of the independent variables did not show any violation of the assumptions of the regression model. The proportional odds assumption was met using a test of parallel lines provided by the ordinal regression output. The model was adjusted for age and sex, and the results are reported as odds ratios (ORs).

All proportions were calculated as percentages of patients with available data. Significance was set at P < 0.05. Patients with missing data were excluded from relevant analyses. The findings are reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement for cohort studies.19 Analyses were performed using SPSS IBM Version 22 (SPSS Inc).

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the human research and ethics committee of each participating hospital and the University of Queensland Medical Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Of 1220 patients who were recruited for the study, medication records at admission were available for 1216. Mean age was 81.3 years (SD, 6.8 years), and median length of stay was 6 days (interquartile range [IQR], 4–11 days). Diagnosis-related groups, recorded for 1211 participants (99.6% of the sample), classified the most frequent primary diagnoses as diseases and disorders of the circulatory system (259 [21.4%]), respiratory system (253 [20.9%]), nervous system (125 [10.3%]) and kidney and urinary tract (96 [7.9%]).

There were significant differences across the polypharmacy categories for several variables (Box 1). The number of medications increased in association with a higher number of comorbidities and a higher prevalence of pain, dyspnoea, and dependence in terms of IADL. In contrast, the number of medications decreased in association with higher prevalence of severe cognitive impairment. There were no significant differences across polypharmacy categories based on dependence in terms of ADL, or presence of fatigue, urinary incontinence, behaviour symptoms, falls or weight loss.

A total of 1173/1216 patients (96.5%) had complete data and were included in the ordinal regression model that was used to identify independent predictors of polypharmacy status from the factors significant in the univariate analysis shown in Box 1. With each additional comorbidity, the odds of being in a higher polypharmacy category on admission increased by 27% (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.20–1.34); patients with pain (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.05–1.64) or dyspnoea (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.30–2.07) or who were dependent in terms of IADL premorbidly (OR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.20–2.41) were also significantly more likely to be in the higher polypharmacy categories (Box 2). In contrast, compared with those with severe cognitive impairment, those with intact cognition (OR, 3.17; 95% CI, 2.05–4.92) or mild to moderate cognitive impairment (OR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.22–3.11) were significantly more likely to be in the higher polypharmacy categories.

Patients with complete medication records on admission and discharge (1187/1216 patients [97.6%]) were prescribed a mean (SD) of 7.1 (3.7) regular medications per day on admission and 7.6 (3.8) on discharge (P < 0.001). There was, however, no significant change in the prevalence of medications such as statins (459 [38.7%] v 457 [38.5%] patients), opioid analgesics (155 [13.1%] v 166 [14.0%] patients), antipsychotics (59 [5.0%] v 65 [5.5%] patients) and benzodiazepines (122 [10.3%] v 135 [11.4%] patients) (data on medications with a prevalence of at least 2% at admission are shown in Appendix 1.

Hyperpolypharmacy was observed in 290/1216 patients (23.8%) at admission and 336/1187 patients (28.3%) on discharge. Most patients (875 [73.7%]) did not change polypharmacy category from admission to discharge; however, 200 (16.8%) changed to a higher polypharmacy category and 112 (9.4%) changed to a lower polypharmacy category, both changes being significant (P < 0.001) (Appendix 2).

There was no significant association with diagnosis-related group category for the 109 patients (9.2%) who were taking < 10 medications at admission but taking 10 or more at discharge. There was no clinically meaningful change in the classification of prescribed medication (symptom control, prevention or both) during the inpatient episode (Box 3). For example, the proportion of purely preventive medications in the hyperpolypharmacy category was 1209/3371 (35.9%) at admission and 1508/4117 (36.6%) at discharge. While there was limited variation in number of prescribed medications according to hospital size, this was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our study showed that three-quarters of older patients assessed were receiving five or more drugs, and more than one-fifth were receiving 10 or more, on admission to hospital. The mean number of prescribed medications per day remained high at discharge, with no clinically meaningful change in the classification (symptom control, prevention or both) of medications, nor in the prevalence of specific drug classes such as statins, opioid analgesics, antipsychotics and benzodiazepines. This may suggest that active attempts were not made to deprescribe when appropriate. Polypharmacy was significantly associated with comorbidity and with symptoms (notably pain and breathlessness) and with worse performance in IADL.

Our study has some limitations. We acknowledge the possibility of selection bias from several sources, including the requirement that patients have an expected hospital stay of at least 48 hours, the recruitment of participants on weekdays only, and the number of patients who declined to participate in the study. The appropriateness of prescribing at the level of individual patients based on clinical indications and contraindications was not considered, and medication doses were not explored. Medications at admission and discharge were documented from patients' prescription charts alone, rather than by complete medication reconciliation using multiple sources of information (patient interview, letter from general practitioner and dispensing history from pharmacy20). Importantly, the design of our study denied us the opportunity to explore whether comorbidities, which may have triggered prescribing of multiple drugs, were the principal cause of the symptoms and functional impairment observed in association with polypharmacy, or whether the polypharmacy itself may have been responsible for some or most of this illness and disability burden, as has been suggested in other studies.21

The strengths of the study are its large cohort of patients recruited across secondary and tertiary care settings and the rigorous assessment of patients' functional and cognitive status.

For all patients, the objectives of health care, including pharmacotherapy, can be summarised as ameliorating symptoms, improving function and delaying death. With increasing age, prolonging life often becomes a less feasible therapeutic goal. Older patients themselves prioritise improvements in mobility and functional status over longer survival.22 In a recent survey, only 3% of community-dwelling older people would take medications for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease if adverse effects were severe enough to affect functioning.23 Our study found that among patients taking 10 or more drugs, more than one in four of these medications were classified as purely preventive, according to mean numbers of drugs per patient, which may constitute an unnecessary treatment burden if clinical benefits are not realised in the short term. In view of our finding of increased prescribing for those with functional impairment, the values and preferences of this patient group should be explored in qualitative studies.

Where and when the process of detailed medication review should occur has not been established. Community medication reviews by pharmacists are an attractive option and have strong face validity. However, several studies of pharmacist-led medication review have shown no positive effect on clinical outcomes or quality of life.24 Perhaps only a medication review underpinned by careful consideration of the health status of the patient concerned, including estimation of life expectancy and exploration of individual goals of care, is likely to result in clinically meaningful outcomes. The acute care hospital ward under the care of physicians is a setting in which these complex decisions could be considered and actions initiated in discontinuing inappropriate medications. While time constraints are a challenge, they are outweighed by the accessibility of the patients' full history and investigations, and the ability to monitor for adverse effects of drug withdrawal in those patients with longer hospital stays.

In conclusion, polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy are common among older people in general medical wards in Australia, with no significant changes in the number or classification of medications between admission and discharge. Patients who are dependent in terms of IADL are at particular risk of polypharmacy. Whether such prescribing in this patient group enhances quality of life and improves longevity or whether it imposes iatrogenic harm and lowers quality of life needs to be established by carefully designed randomised controlled trials of interventions designed to minimise inappropriate polypharmacy.

1 Categories of medication prescribing on admission in relation to patient characteristics*

Category | All categories | Non-polypharmacy (0–4 drugs) | Polypharmacy (5–9 drugs) | Hyperpolypharmacy (≥ 10 drugs) | P | ||||||||||

Total, n (%) | 1216 (100.0%) | 291 (23.9%) | 635 (52.2%) | 290 (23.8%) | |||||||||||

Demographics | |||||||||||||||

Age in years, mean (SD) | 81.3 (6.8) | 81.4 (6.9) | 81.7 (7.0) | 80.4 (6.3) | 0.03 | ||||||||||

Women | 659/1216 (54.2%) | 151/291 (51.9%) | 358/635 (56.4%) | 150/290 (51.7%) | 0.28 | ||||||||||

Admission source | 0.24 | ||||||||||||||

Community | 1061/1215 (87.3%) | 261/290 (90.0%) | 552/635 (86.9%) | 248/290 (85.5%) | |||||||||||

Institution | 154/1215 (12.7%) | 29/290 (10.0%) | 83/635 (13.1%) | 42/290 (14.5%) | |||||||||||

Length of stay in days, median (IQR) | 6 (4–11) | 7 (4–13) | 6 (3–10) | 6 (4–10) | 0.31 | ||||||||||

Discharge destination or outcome | 0.01 | ||||||||||||||

Community | 792/1215 (65.2%) | 184/291 (63.2%) | 419/634 (66.1%) | 189/290 (65.2%) | |||||||||||

Other inpatient care | 182/1215 (15.0%) | 46/291 (15.8%) | 103/634 (16.2%) | 33/290 (11.4%) | |||||||||||

Residential aged care facility | 189/1215 (15.6%) | 45/291 (15.5%) | 97/634 (15.3%) | 47/290 (16.2%) | |||||||||||

Died | 52/1215 (4.3%) | 16/291 (5.5%) | 15/634 (2.4%) | 21/290 (7.2%) | |||||||||||

Comorbidities | |||||||||||||||

No. of comorbidities at admission, mean (SD) | 6.2 (2.3) | 5.2 (2.3) | 6.3 (2.1) | 7.0 (2.1) | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

Geriatric syndromes | |||||||||||||||

Short ADL scale at admission, median (IQR)† | 2 (0–6) | 3 (0–8) | 2 (0–6) | 2 (0–7) | 0.26 | ||||||||||

Premorbid IADL‡ | 0.001 | ||||||||||||||

Independent | 164/1216 (13.5%) | 56/291 (19.2%) | 84/635 (13.2%) | 24/290 (8.3%) | |||||||||||

Dependent | 1052/1216 (86.5%) | 235/291 (80.8%) | 551/635 (86.8%) | 266/290 (91.7%) | |||||||||||

Cognitive status at admission | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||||

Intact (0 or 1) | 837/1210 (69.2%) | 174/290 (60.0%) | 436/631 (69.1%) | 227/289 (78.5%) | |||||||||||

Mild/moderate impairment (2–4) | 272/1210 (22.5%) | 75/290 (25.9%) | 149/631 (23.6%) | 48/289 (16.6%) | |||||||||||

Severe impairment (5 or 6) | 101/1210 (8.3%) | 41/290 (14.1%) | 46/631 (7.3%) | 14/289 (4.8%) | |||||||||||

Urinary incontinence at admission |

| 0.65 | |||||||||||||

Not present | 879/1216 (72.3%) | 215/291 (73.9%) | 452/635 (71.2%) | 212/290 (73.1%) | |||||||||||

Present | 337/1216 (27.7%) | 76/291 (26.1%) | 183/635 (28.8%) | 78/290 (26.9%) | |||||||||||

Behaviour symptoms at admission§ | 0.12 | ||||||||||||||

Not present | 1142/1214 (94.1%) | 271/291 (93.1%) | 592/634 (93.4%) | 279/289 (96.5%) | |||||||||||

Present | 72/1214 (5.9%) | 20/291 (6.9%) | 42/634 (6.6%) | 10/289 (3.5%) | |||||||||||

Falls in the 90 days before admission | 0.34 | ||||||||||||||

None | 727/1215 (59.8%) | 173/291 (59.5%) | 370/634 (58.4%) | 184/290 (63.4%) | |||||||||||

At least one | 488/1215 (40.2%) | 118/291 (40.5%) | 264/634 (41.6%) | 106/290 (36.6%) | |||||||||||

Weight loss¶ | 0.56 | ||||||||||||||

No | 911/1197 (76.1%) | 211/284 (74.3%) | 475/625 (76.0%) | 225/288 (78.1%) | |||||||||||

Yes | 286/1197 (23.9%) | 73/284 (25.7%) | 150/625 (24.0%) | 63/288 (21.9%) | |||||||||||

Symptoms | |||||||||||||||

Pain at admission | 0.007 | ||||||||||||||

Not present | 557/1198 (46.5%) | 155/285 (54.4%) | 281/627 (44.8%) | 121/286 (42.3%) | |||||||||||

Present | 641/1198 (53.5%) | 130/285 (45.6%) | 346/627 (55.2%) | 165/286 (57.7%) | |||||||||||

Dyspnoea at admission | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||||

Not present | 511/1197 (42.7%) | 159/289 (55.0%) | 270/624 (43.3%) | 82/284 (28.9%) | |||||||||||

Present | 686/1197 (57.3%) | 130/289 (45.0%) | 354/624 (56.7%) | 202/284 (71.1%) | |||||||||||

Fatigue at admission | 0.31 | ||||||||||||||

Not present | 806/1195 (67.4%) | 199/290 (68.6%) | 426/621 (68.6%) | 181/284 (63.7%) | |||||||||||

Present | 389/1195 (32.6%) | 91/290 (31.4%) | 195/621 (31.4%) | 103/284 (36.3%) | |||||||||||

ADL = activities of daily living. IADL = instrumental ADL. * Data are numerator/denominator (%) unless otherwise indicated. † The ADL short-form scale comprises four items (personal hygiene, walking, toilet use and eating); range is 0–16, with higher scores reflecting greater level of dependency. ‡ Premorbid IADL performance is assessed on seven items (meal preparation, ordinary housework, managing finances, managing medications, using the telephone, shopping and transportation); scores on each item range from 0 (independent) to 6 (total dependence), and a score of ≥ 2 on any item indicates IADL dependence. § Includes the presence of one or more of the following: verbal abuse, physical abuse, resisting care, and socially inappropriate or disruptive behaviour. ¶ Loss of ≥ 5% bodyweight in the 30 days before admission or ≥ 10% in the 180 days before admission. | |||||||||||||||

2 Ordinal regression model of factors associated with increasing polypharmacy*

Factor | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P | |||||||||||||

Number of comorbidities | 1.27 (1.20–1.34) | < 0.001 | |||||||||||||

Pain at admission | 1.31 (1.05–1.64) | 0.02 | |||||||||||||

Dyspnoea at admission | 1.64 (1.30–2.07) | < 0.001 | |||||||||||||

Premorbid IADL — dependent | 1.70 (1.20–2.41) | 0.003 | |||||||||||||

Cognitive status at admission | |||||||||||||||

Intact (0 or 1) | 3.17 (2.05–4.92) | < 0.001 | |||||||||||||

Mild/moderate impairment (2–4) | 1.95 (1.22–3.11) | 0.005 | |||||||||||||

Severe impairment (5 or 6) | Reference | — | |||||||||||||

IADL = instrumental activities of daily living. * Adjusted for age and sex. | |||||||||||||||

Received 3 December 2013, accepted 22 October 2014

- Ruth E Hubbard1

- Nancye M Peel1

- Ian A Scott1,2

- Jennifer H Martin1,3

- Alesha Smith1

- Peter I Pillans2

- Arjun Poudel1

- Leonard C Gray1

- 1 University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD.

- 2 Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, QLD.

- 3 University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, et al. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2012; 65: 989-995.

- 2. Bellelli G, Magnifico F, Trabucchi M. Outcomes at 12 months in a population of elderly patients discharged from a rehabilitation unit. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2008; 9: 55-64.

- 3. Egger SS, Bachmann A, Hubmann N, et al. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly patients: comparison between general medical and geriatric wards. Drugs Aging 2006; 23: 823-837.

- 4. Wahab MS, Nyfort-Hansen K, Kowalski SR. Inappropriate prescribing in hospitalised Australian elderly as determined by the STOPP criteria. Int J Clin Pharm 2012; 34: 855-862.

- 5. Hamilton H, Gallagher P, Ryan C, et al. Potentially inappropriate medications defined by STOPP criteria and the risk of adverse drug events in older hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171: 1013-1019.

- 6. Davies EC, Green CF, Taylor S, et al. Adverse drug reactions in hospital in-patients: a prospective analysis of 3695 patient-episodes. PLOS One 2009; 4: e4439.

- 7. Sanossian N, Ovbiagele B. Prevention and management of stroke in very elderly patients. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 1031-1041.

- 8. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med 2015; Mar 23. [Epub ahead of print.]

- 9. Hubbard RE, O'Mahony MS, Woodhouse KW. Medication prescribing in frail older people. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2013; 69: 319-326.

- 10. Brand CA, Martin-Khan M, Wright O, et al. Development of quality indicators for monitoring outcomes of frail elderly hospitalised in acute care health settings: study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res 2011; 11: 281.

- 11. Lakhan P, Jones M, Wilson A, et al. A prospective cohort study of geriatric syndromes among older medical patients admitted to acute care hospitals. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59: 2001-2008.

- 12. Travers C, Byrne G, Pachana N, et al. Prospective observational study of dementia and delirium in the acute hospital setting. Intern Med J 2013; 43: 262-269.

- 13. Gray L, Ariño-Blasco S, Berg K, et al. interRAI acute care (AC) assessment form and user's manual. Washington, DC: interRAI, 2010.

- 14. Gray LC, Bernabei R, Berg K, et al. Standardizing assessment of elderly people in acute care: the interRAI Acute Care instrument. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56: 536-541.

- 15. Gray L, Ariño-Blasco S, Berg K, et al. interRAI clinical and management applications manual for use with the interRAI acute care assessment instrument. Version 9.1. Washington, DC: interRAI, 2013.

- 16. Currow DC, Stevenson JP, Abernethy AP, et al. Prescribing in palliative care as death approaches. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55: 590-595.

- 17. Lee HR, Yi SY, Kim do Y. Evaluation of prescribing medications for terminal cancer patients near death: essential or futile. Cancer Res Treat 2013; 45: 220-225.

- 18. Onder G, Liperoti R, Fialova D, et al. Polypharmacy in nursing home in Europe: results from the SHELTER study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2012; 67: 698-704.

- 19. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007; 370: 1453-1457.

- 20. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Taking a best possible medication history. http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/medication-safety/medication-reconciliation/taking-a-best-possible-medication-history (accessed May 2013).

- 21. Peron EP, Gray SL, Hanlon JT. Medication use and functional status decline in older adults: a narrative review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2011; 9: 378-391.

- 22. Rockwood K, Joyce B, Stolee P. Use of goal attainment scaling in measuring clinically important change in cognitive rehabilitation patients. J Clin Epidemiol 1997; 50: 581-588.

- 23. Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Towle V, et al. Effects of benefits and harms on older persons' willingness to take medication for primary cardiovascular prevention. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171: 923-928.

- 24. Lenaghan E, Holland R, Brooks A. Home-based medication review in a high risk elderly population in primary care – the POLYMED randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2007; 36: 292-297.

Emily Reeve

Barriers for medical practitioners deprescribing identified in a systematic review,(2) in which 1/21 studies was conducted in hospital doctors, may be particularly pertinent to hospital practice. The culture is to prescribe more medications (which may be enhanced in acute illness), with stopping a lower priority. Inertia in work practice, and reluctance to question a colleague’s prescribing decisions, may lead to prescribing medications taken prior to admission without review. Junior doctors (who usually chart prescriptions) may have limited confidence in their knowledge of geriatric pharmacology(3) and ability to review medications, or may not feel that medication review is their role. Geriatricians report they are more likely to deprescribe medications for patients with polypharmacy and underlying cognitive impairment or limited life expectancy.(4) Perspectives of other health professionals are unknown and further research is needed.

Patient barriers to deprescribing in hospital should also be considered. Most patients are willing to consider deprescribing.(5) However, discussion is required to overcome fears and beliefs that it is appropriate to continue medication(5) which may be beyond the time constraints of an acute admission, for both doctors and pharmacists. Studies are needed to determine whether an acute admission makes patients more open to changing their long-term medicines, or induces patients to cling to them.

1. Hubbard RE, Peel NM, Scott IA et al. Polypharmacy among inpatients aged 70 years or older in Australia. Med J Aust 2015; 202 :373-377.

2. Anderson K, Freeman C, Stowasser D, Scott I. Prescriber barriers and enablers to minimising potentially inappropriate medications in adults: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e006544.

3. Cullinan S, Fleming A, O'Mahony D, et al. Doctors’ perspectives on the barriers to appropriate prescribing in older hospitalized patients: A qualitative study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014; 79: 860-869

4. Ni Chroinin D, Ni Chroinin C, Beveridge A. Factors influencing deprescribing habits among geriatricians. Age Ageing 2015; published online March 10

5. Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, et al. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013; 30: 793-807.

Competing Interests: No relevant disclosures

Dr Emily Reeve

University of Sydney and Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney NSW