Clinical record

An 86-year-old man, a retired structural engineer, was referred to our tertiary centre with a 3-week history of New York Heart Association Class III–IV heart failure symptoms. Past medical history included bioprosthetic aortic valve (23 mm Perimount) implanted 10 years previously for severe aortic stenosis due to age-related degeneration, ischaemic heart disease (coronary artery bypass grafting in 2003), chronic kidney disease stage 2, dyslipidaemia, and previous smoking. He had been closely followed by his local cardiologist with slowly progressive dysfunction of the aortic valve replacement, thought to represent prosthetic valve degeneration, which was asymptomatic and managed conservatively. Importantly, there were no symptoms or clinical suspicion of chronic endocarditis. A sudden clinical deterioration, with clinical signs of left ventricular failure, prompted a referral to hospital.

On examination, the patient was haemodynamically stable and afebrile. There were no peripheral stigmata of infective endocarditis. His jugular venous pressure was raised at 5 cm, and he had lower limb pitting oedema. Bibasilar crackles were noted on chest auscultation, and there were murmurs consistent with mixed prosthetic valve stenosis and regurgitation. The patient's abdomen was soft, with no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly.

Laboratory investigations showed a white blood cell count of 10.2 × 109/L (reference interval [RI], 3.5–11.0 × 109/L), a haemoglobin level of 120 g/L (RI, 120–180 g/L) and a platelet count of 149 × 109/L (RI, 140–400 × 109/L). Chest x-ray showed cardiomegaly.

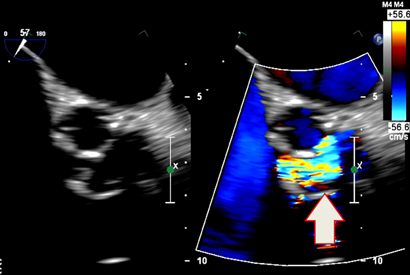

Transthoracic echocardiography showed severe prosthetic valve aortic regurgitation and thickening of the prosthetic valve leaflets with moderate aortic stenosis, with a maximum gradient of 96 mmHg and a mean gradient of 51 mmHg. Transoesophageal echocardiography confirmed severe transvalvular aortic regurgitation and thickened prosthetic valve leaflets, but no defined vegetations were present (Box 1).

Three sets of blood samples were cultured, the results of which were all negative. Cardiac catheterisation showed native triple vessel coronary disease, a patent left internal mammary arterial graft and mildly diseased but patent venous grafts.

Based on the patient's presenting signs and echocardiography findings, it was concluded that repeat aortic valve replacement was indicated. His case was discussed at the multidisciplinary heart valve team meeting to decide between valve-in-valve transcutaneous aortic valve implantation (TAVI) and redo sternotomy and surgical aortic valve replacement. The consensus was for repeat cardiac surgery with a redo bioprosthetic aortic valve.

The patient's condition was stabilised medically, and he underwent a redo sternotomy and transverse aortotomy. Macroscopic assessment of the explanted bioprosthetic aortic valve showed significant structural deterioration, with calcified central nodularity on all three leaflets surrounded by erythema, and destruction of leaflet tissue (Box 2). A 23 mm Perimount valve (Edwards Lifesciences) was secured in place. He developed atrial fibrillation after surgery, which was managed medically. The patient's recovery was otherwise uncomplicated, and he was discharged home 8 days after surgery.

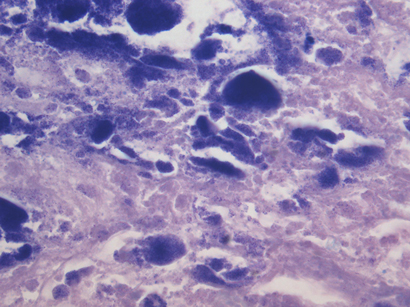

Pathological examination of the specimen showed marked nodular fibrosis and calcification. Preliminary microscopy and cultures of operative specimens revealed no microorganisms. However, transmission electron microscopy of tissue sections confirmed intracellular organisms, in keeping with Coxiella burnetii chronic active endocarditis (Box 3 and Box 4).

The patient and his general practitioner and cardiologist were immediately informed, and the patient was commenced on 18 months' doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine therapy, under advice from the infectious diseases team.

Q fever serological investigations subsequently showed antiphase I IgG titre of 3200 (normal titre, < 800), which represented chronic Q fever. Further detailed history-taking ruled out any known Q fever infection in the past, contact with farm animals or consumption of unpasteurised milk. However, he lives in a regional area of Australia, which is endemic for C. burnetii.

The bacterium C. burnetii is a small, obligate intracellular gram-negative organism that was first described by Derrick in Australia in 1937.1 Q fever is a zoonosis transmitted from its primary reservoirs, usually farm animals, to humans mainly via inhalation but also by consuming unpasteurised dairy products.2 C. burnetii infection can affect the liver, spleen, skin, lungs, kidneys and central nervous system. Cardiac manifestations include culture-negative endocarditis, myocarditis and pericarditis.2 Presenting symptoms are usually non-specific and protean, making the diagnosis, particularly of chronic Q fever, challenging.

Q fever endocarditis (QFE) is one of the main causes of culture-negative endocarditis.3 Degenerated and damaged native aortic or mitral valves are most commonly targeted by C. burnetii.2 Prosthetic valves and prior valve surgery also predispose to QFE.4

The diagnosis of QFE is usually based on serological investigations, bacterial cultures and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. Echocardiography may detect valvular vegetation in only 30% of cases.5

QFE is a potentially fatal disease if not diagnosed and treated in time.5 It has been recommended that patients with prosthetic valves but without infective endocarditis who are successfully treated for acute Q fever should have serological follow-up every 4 months for 2 years.6 In the setting of QFE, due to risk of relapse even after successful treatment, it is recommended that patients should have serological follow-up for at least 5 years.7

This case provides a unique learning point that QFE of a prosthetic valve (QFE-PV) can present as silently progressive, asymptomatic prosthetic valve dysfunction. In the past 5 years, 13 patients with progressive bioprosthetic valve dysfunction were found to have infective endocarditis at redo surgery at the Prince Charles Hospital in Brisbane, Queensland; two of these cases were due to QFE-PV. Clinicians should have a low threshold for investigation of QFE-PV in patients with prosthetic heart valves living in a region endemic for Q fever.

A second issue is the performance of Q fever serological investigations before consideration for TAVI. If TAVI were to occur in the context of unsuspected C. burnetii infection, the infection is likely to go undetected and result in early degeneration of the prosthesis from recurrent endocarditis.

In conclusion, QFE-PV is an unsuspected cause of prosthetic valve dysfunction, but may be present in a proportion of patients requiring redo surgery. QFE-PV should be suspected in patients with degenerative heart valve replacements living in C. burnetii endemic countries such as Australia. Increased physician awareness of this condition, and early performance of C. burnetii serological investigations for any patient with early prosthetic valve dysfunction (regurgitation or stenosis), is recommended.

Lessons from practice

- Q fever endocarditis of a prosthetic valve can result in premature prosthetic valve dysfunction among patients with cardiac valve replacements.

- Clinicians should have a low threshold to exclude Q fever endocarditis of a prosthetic valve in a patient with prosthetic valve dysfunction who lives in a Q fever endemic region.

- After successful treatment of acute Q fever endocarditis, regular follow-up is required to detect and treat chronic Q fever.

- 1. Derrick EH. “Q” fever, a new fever entity: clinical features, diagnosis and laboratory investigation. Med J Aust 1937; 2: 281-299.

- 2. Maurin M, Raoult D. Q fever. Clin Microbiol Rev 1999; 12: 518-553.

- 3. Hoen B, Selton-Suty C, Lacassin F, et al. Infective endocarditis in patients with negative blood cultures: analysis of 88 cases from a one-year nationwide survey in France. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 20: 501-506.

- 4. Kampschreur LM, Dekker S, Hagenaars JC, et al. Identification of risk factors for chronic Q fever, the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 2012; 18: 563-570.

- 5. Raoult D. Chronic Q fever: expert opinion versus literature analysis and consensus. J Infect 2012; 65: 102-108.

- 6. Gunn TM, Raz GM, Turek JW, Farivar RS. Cardiac manifestations of Q fever infection: case series and a review of the literature. J Card Surg 2013; 28: 233-237.

- 7. Million M, Thuny F, Richet H, Raoult D. Long-term outcome of Q fever endocarditis: a 26-year personal survey. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10: 527-535.

No relevant disclosures.