Abstract

Objectives: To describe the services provided to young people aged 12–25 years who attend headspace centres across Australia, and how these services are being delivered.

Design: A census of headspace clients commencing an episode of care between 1 April 2013 and 31 March 2014.

Participants: All young people first attending one of the 55 fully established headspace centres during the data collection period (33 038 young people).

Main outcome measures: Main reason for presentation, wait time, service type, service provider type, funding stream.

Results: Most young people presented for mental health problems and situational problems (such as bullying or relationship problems); most of those who presented for other problems also received mental health care services as needed. Wait time for the first appointment was 2 weeks or less for 80.1% of clients; only 5.3% waited for more than 4 weeks. The main services provided were a mixture of intake and assessment and mental health care, provided mainly by psychologists, intake workers and allied mental health workers. These were generally funded by the headspace grant and the Medicare Benefits Schedule.

Conclusions: headspace centres are providing direct and indirect access to mental health care for young people.

headspace, the National Youth Mental Health Foundation, was initiated by the Australian Government in 2006 because it was recognised that the prevalence of mental disorders and the burden of disease associated with mental health problems was greater for those in their adolescent and early adult years than in older adults, but that young people were less likely to access professional help.1 headspace centres aim to be highly accessible, youth-friendly integrated service hubs that respond to the mental health, general health, alcohol and other drug, and vocational concerns of young people aged 12 to 25 years.2 The main goal is to improve mental health outcomes by reducing help-seeking barriers and facilitating early access to services that meet the holistic needs of young people. Recent data indicate that the initiative is largely achieving its aim to improve access to services early in the development of mental illness.3

As the headspace network has grown, the key components of the model have become clearer.4 At the heart of all headspace services is a youth-friendly, non-stigmatising, inclusive “no wrong door” approach, essential for engaging young people in mental health care.5 This is both a challenge and a major point of difference from other mental health services, which are often highly targeted, with clear exclusion criteria. Consequently, there has been a high level of demand for the services offered by headspace.3Centres have been set up across Australia in highly diverse community settings with a flexible local capacity for service delivery. The variation in focus between centres and in the types of services they offer has been noted as both a strength and a concern.6 Workforce problems are an ongoing challenge for many centres, particularly in rural and remote locations.7

headspace aims to provide a timely and appropriate response to the various problems presented by young people, and to provide a soft entry point to mental health care. In this study we set out to investigate what services headspace centres are providing to young people and how they are being delivered. The proportions of young people who initially presented in each of the main service streams — mental health, situational, physical health, alcohol and other drugs, and vocational health — were determined, as were the numbers of clients who received mental health care at headspace centres after initially presenting to the service for other reasons. We examined the waiting time for services, patterns of service use (number of sessions of each service type attended, types of service mix), as well as the major providers and the funding streams that support service delivery.

Methods

Participants and procedures

All participants had commenced an episode of care at a headspace centre between 1 April 2013 and 31 March 2014.

Data were drawn from the headspace Minimum Data Set,3 which includes the routine data collected from all clients who provide consent, producing a near-complete census of headspace clients. Young people enter data into an electronic form before each service visit, and service providers also submit relevant information about each visit. Data were de-identified by encryption and extracted to the headspace national office data warehouse.

Ethics approval was obtained through internal quality assurance processes; these consent processes were reviewed and endorsed by an independent body, Australasian Human Research Ethics Consultancy Services. Follow-up data collection was approved by Melbourne Health Quality Assurance.

Measures

- The main presenting problem or concern was categorised by the service provider as: mental health or behavioural (symptoms of a mental health problem); situational (eg, bullying at school, difficulty with personal relationships, grief); physical or sexual health; alcohol or other drugs (AOD); vocational; or other.

- The service type was categorised as one of the following on each occasion of service: mental health; physical or sexual health; AOD; vocational; or engagement and assessment. The number of sessions of each main service type attended by a young person during the data collection period was calculated.

- The wait time was measured by asking clients how long they had waited after requesting an appointment for their first service appointment, and whether they thought they had been required to wait too long.

- Service providers were categorised by profession and role. This included intake and youth workers, psychologists, allied mental health workers (social workers, mental health nurses and occupational therapists), general practitioners, nurses, psychiatrists, AOD workers, vocational workers, clinical leads and administrative staff (including reception staff, managers and practice managers).

- The funding stream was categorised as: the headspace grant (each centre is funded through a headspace grant); the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS); Access to Allied Psychological Services (ATAPS); the Mental Health Nurse Initiative (MHNI); Rural Primary Health Services (RPHS); in-kind contributions by partner organisations; or other.

Results

Data were assessed for 33 038 young people who had commenced an episode of care at one of 55 established headspace centres during the study period; 16.8% were aged 12–14 years, 34.4% aged 15–17 years, 25.8% aged 18–20 years, and 23.0% were 21–25 years of age. Most were female (61.9%); 37.5% were male.

Main presenting problems or concerns

The proportions of young people who attended headspace centres for each category of main presenting problem or concern and the number of service sessions they attended are shown in Box 1. Almost three-quarters of presentations specifically involved mental health and behavioural problems; 13.4% were for situational problems and 7.1% for physical or sexual health concerns. Only a small proportion (3.1%) presented primarily for AOD problems, and very few (1.8%) for vocational reasons.

The vast majority of clients, regardless of their initial problem or concern, attended mental health sessions; this included almost all who presented with situational or AOD problems, and almost 85% of those who presented with a vocational problem. The exception was that less than half of those who presented with physical or sexual health concerns also used mental health services.

Clients who first presented for mental health reasons attended the most service sessions, with an average of 4.4 and a median of 3.0 sessions per person. More than a quarter of these young people attended six or more sessions, and more than 10% attended 10 or more. Less than a third attended only once for mental health consultations.

Those who first presented for a physical or sexual health problem attended the fewest service sessions.

Wait time

Most of the young people reported that they did not wait too long for their first appointment (Box 1).

According to their detailed responses, 38.9% of clients had waited less than one week for their first appointment, 41.2% for 1–2 weeks, 14.6% for 3–4 weeks, and only 5.3% had waited more than 4 weeks. Unsurprisingly, almost half of those who had to wait more than 4 weeks reported that they had waited too long.

Service mix

headspace clients typically attend at least one session of engagement and assessment, except those who present primarily for physical or sexual health problems. The time used for engagement and assessment increased with the total number of sessions attended, regardless of the initial presenting problem (see Appendix).

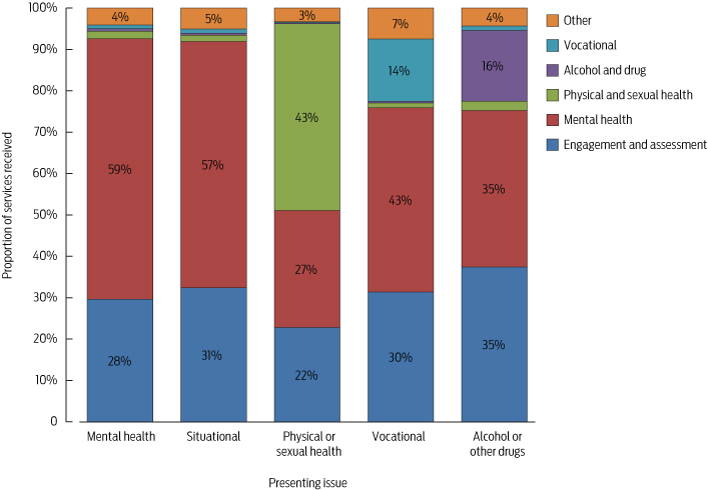

Box 2 shows the proportions of each type of service provision for each of the core streams accessed by clients with different initial reasons for presenting. These data show the strong similarity in service patterns for those who presented with mental health and situational problems. Young people who first presented with situational concerns received slightly more engagement and assessment, but were otherwise similar to those who presented with mental health problems.

Young people presenting with physical or sexual health problems had quite a different pattern to those presenting with other concerns, although there was still a large component of engagement and assessment and mental health treatment. Young people who presented for AOD problems tended to have a greater need for engagement and assessment.

Service providers and funding streams

The service providers that delivered most of each service type are shown in Box 3A. In line with the headspace service model — young people usually have an engagement and assessment session with an intake or youth worker during their initial appointment to gather information and to determine their needs — intake and youth workers provided almost half of the engagement and assessment service, followed by psychologists, who delivered almost 20%. Other allied mental health workers, including social workers and occupational therapists, provided just over 12%.

Mental health services were mostly delivered by allied mental health professionals (81%), with over half provided by psychologists; only 1.2% was provided by psychiatrists, and just over 10% by general practitioners. Almost all physical or sexual health service was provided by GPs or nurses. Specialist AOD workers undertook a third of AOD service, complemented by contributions from allied mental health workers. The small amount of vocational service was largely provided by specialised vocational workers, although a quarter was undertaken by intake and youth workers.

The provision of headspace services relies on a number of funding streams. The major sources for each service type are compiled in Box 3B. Engagement and assessment services were mostly funded by the headspace grant (71%) or through the MBS (21%). Nearly two-thirds of mental health services were funded by the MBS and a smaller contribution by the ATAPS program, with just under a third funded by the headspace grant. Physical and sexual health services were primarily funded through MBS items, but 22% was supported by headspace grant funds. In contrast, the main funding source for AOD and vocational services was in-kind support by co-located services or consortium partners.

It should be noted that there was variation between headspace centres in each of the parameters discussed here, but space precludes the presentation of detailed analyses. Generally, however, no major differences were associated with the size, age or geographical location of centres. The one exception was waiting too long; significantly fewer young people reported waiting too long at the most recently established centres than at centres established during the first three rounds of the headspace program (7.0% v. 10.6%; P < 0.001). The longest wait times were experienced in one large centre in a major city, where 27% of young people reported they had waited too long, compared with only 2% at each of a small inner regional and a medium-sized outer regional centre. Waiting too long was significantly more common at large centres (12.0%) than at medium (9.6%) and small (9.4%) centres (P < 0.001). It was also significantly more frequent in major cities (11.9%) than at inner regional, outer regional and remote centres (8.3%, 9.2% and 8.1%, respectively; P < 0.001).

Discussion

There is considerable interest in the headspace initiative because it comprises a significant investment by the Australian Government in an innovative approach to youth mental health. The results presented here show that the vast majority of young people specifically attend headspace centres for mental health problems, and that the next most common reason for attendance involves situational problems that affect the wellbeing of the young person, such as bullying at school, difficulty with personal relationships or grief. This is consistent with the general early intervention aim of the headspace initiative, and with the recognition that mental health problems and related risk factors are the primary health concerns for adolescents and young adults.8

A sizeable minority of young people initially attended headspace for physical or sexual health problems. For almost half of these clients, this led to a mental health consultation, supporting the contention that physical and sexual health care can and should be a pathway to mental health care (and vice versa).

The headspace initiative engages young people with a range of health and wellbeing concerns, not just those with mental health problems. Few clients, however, presented primarily for AOD problems and vocational difficulties, suggesting that these are more often accompanying problems than primary concerns for those attending headspace centres, although half of the headspace clients aged 17–25 years are looking for work (compared with less than 10% for this age group in the general population).9 Funding for these two core streams relied primarily on in-kind contributions by headspace service partners, emphasising the value of the local partnership model that underpins service delivery, but also revealing vulnerability in terms of stable funding. Building the capacity of the headspace model to better support young people with vocational needs and secondary AOD problems should be a priority.

As young people are often reluctant to attend mental health services, receiving an appointment promptly after a young person has decided to seek help is crucial. The vast majority of headspace clients waited 2 weeks or less for initial service, a notable achievement. Wait times are a major barrier in traditional mental health services,10 and minimising waiting is a distinguishing focus of headspace. Nevertheless, some clients waited longer, and wait times were longer in more established centres. Minimising wait times must remain a constant focus for headspace services, while continuing to respond to the growing demands of young people with a range of presenting problems. Engagement and assessment are also critical elements.

Australia claims to lead the world in innovative approaches to youth mental health care. Our results confirm patterns that diverge from traditional mental health service delivery, and we argue that these patterns are more appropriate for meeting the social and mental health needs of young people.5

1 Number of headspace service sessions attended (all types) and initial wait time for young people presenting with different categories of problem or concern

Main reason for presenting to headspace | |||||||||||||||

All clients | Mental health and behaviour | Situational | Physical or sexual health | Alcohol or other drugs | Vocational | ||||||||||

Number of presentations (% of all clients) | 33 038† | 24 034 | 4440 | 2332 | 1030 | 583 | |||||||||

Number who received mental health service | 31 134 | 23 738 | 4331 | 1134 | 951 | 493 | |||||||||

Mean number of sessions attended (SD) | 4.1 (4.2) | 4.4 (4.4) | 3.6 (3.7) | 2.5 (2.9) | 3.0 (3.4) | 3.2 (3.6) | |||||||||

Median number of sessions attended | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | |||||||||

Number of sessions attended | |||||||||||||||

1 session | 35.4% | 32.1% | 39.0% | 50.8% | 45.2% | 45.5% | |||||||||

2 sessions | 14.0% | 12.8% | 14.8% | 22.2% | 19.3% | 16.1% | |||||||||

3–5 sessions | 25.6% | 26.7% | 25.7% | 18.7% | 21.0% | 22.3% | |||||||||

6–9 sessions | 15.1% | 16.9% | 13.3% | 4.6% | 10.0% | 9.8% | |||||||||

10 or more sessions | 10.0% | 11.5% | 7.2% | 3.6% | 4.6% | 6.3% | |||||||||

Client did not wait too long for first service | 89.4% | 88.7% | 91.5% | 90.9% | 91.4% | 92.1% | |||||||||

* Includes engagement and assessment services. † Includes 619 young people (1.9% of sample) who had presented for “other” primary reasons not included in the five major categories, such as attention deficit and developmental disorders. | |||||||||||||||

3 Main service providers (A) and main funding sources (B) for each headspace service type*

(A)

Main types of service providers (rank) | |||||||||||||||

Service type | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||||||||

Engagement and assessment | Intake/youth worker | Psychologist | Allied mental health | GP | |||||||||||

Mental health | Psychologist | Allied mental health | Intake/youth worker | GP | |||||||||||

Physical or sexual health | GP | Nurse | |||||||||||||

Alcohol or drugs | AOD worker | Allied mental health | Intake/youth worker | Psychologist | |||||||||||

Vocational | Vocational | Intake/youth worker | Miscellaneous† | Psychologist | |||||||||||

(B)

Main funding sources (rank) | |||||||||||||||

Service type | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||

Engagement and assessment | headspace | MBS | |||||||||||||

Mental health | MBS | headspace | ATAPS | ||||||||||||

Physical or sexual health | MBS | headspace | In-kind | ||||||||||||

Alcohol or drugs | In-kind | headspace | MBS | ||||||||||||

Vocational | In-kind | headspace | MBS | ||||||||||||

AOD = alcohol or drugs; ATAPS = Access to Allied Psychological Services; GP = general practitioner; MBS = Medical Benefits Scheme.

* A maximum of four service providers and three funding sources are reported here; contributions under 5% are not included. For these reasons, rows do not add to 100%.

† Consisting of various types of provider, mainly interns and placement, community engagement and education officers.

Received 8 December 2014, accepted 23 April 2015

- Debra J Rickwood1,2

- Nic R Telford2

- Kelly R Mazzer2

- Alexandra G Parker2

- Chris J Tanti2

- Patrick D McGorry3

- 1 University of Canberra, Canberra, ACT.

- 2 headspace National Youth Mental Health Foundation, Melbourne, VIC.

- 3 Orygen Youth Health Research Centre, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC.

headspace The National Youth Mental Health Foundation is funded by the Australian Government.

All authors are employed by or directly involved with headspace The National Youth Mental Health Foundation.

- 1. Slade T, Johnston A, Teesson M, et al. The mental health of Australians 2: Report on the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2009. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-pubs-m-mhaust2 (accessed Apr 2015).

- 2. McGorry PD, Tanti C, Stokes R, et al. headspace: Australia's National Youth Mental Health Foundation — where young minds come first. Med J Aust 2007; 187: S68-S70. <MJA full text>

- 3. Rickwood D, Telford N, Parker A, et al. headspace — Australia's innovation in youth mental health: who are the clients and why are they presenting? Med J Aust 2014; 200: 108-111. <MJA full text>

- 4. Rickwood DJ, Anile G, Telford N, et al. Service Innovation Project component 1: Best practice framework. Melbourne: headspace National Youth Mental Health Foundation, 2014.

- 5. McGorry PD, Goldstone SD, Parker AG, et al. Cultures for mental health care of young people: an Australian blueprint for reform. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014; 1: 559-568.

- 6. Rickwood DJ, van Dyke N, Telford N. Innovation in youth mental health services in Australia: Common characteristics across the first headspace centres. Early Interv Psychiatry 2015; 9: 29-37.

- 7. Carbone S, Rickwood DJ, Tanti C. Workforce shortages and their impact on Australian youth mental health reform. Adv Mental Health 2011; 10: 89-94.

- 8. McGorry PD, Purcell R, Hickie IB, Jorm AF. Investing in youth mental health is a best buy. Med J Aust 2007; 187 (7 Suppl): S5-S7. <MJA full text>

- 9. Rickwood DJ, Telford NR, Parker AG et al. headspace ― Australia's innovation in youth mental health: Who's coming and why do they present? Med J Aust 2014; 200: 454. <MJA full text>

- 10. Kowalewski K, McLennan JD, McGrath PJ. A preliminary investigation of wait times for child and adolescent mental health services in Canada. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011; 20: 112-119.

Anthony Jorm

Competing Interests: I have previously worked and published with two of the authors.

Prof Anthony Jorm

University of Melbourne

Debra Rickwood

Competing Interests: Co-author of article and directly funded by headspace

Prof Debra Rickwood

University of Canberra

Anthony Jorm

The website also states that the data show that headspace provides “better access to safe and streamlined care for young people”. However, no data on safety are reported in the articles. Do the authors have any data on adverse events, including suicide and self-harm?

1. Orygen: the National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health. New data shows headspace improving outcomes for young people. https://orygen.org.au/About/News-And-Events/New-data-shows-headspace-improving-outcomes (accessed 12 June 2015).

Competing Interests: I have previously worked and published with two of the authors.

Prof Anthony Jorm

University of Melbourne