Australia, like many developed countries, has a shortage of doctors. While this is disputed by some,1 the literature highlights current and projected shortages of skilled clinicians relative to the demand.2-15 One response to this imbalance is to utilise international medical graduates (IMGs).

The Medical Board of Australia is responsible for the registration of all doctors in Australia and sets the relevant standards, codes and guidelines. The Australian Medical Council (AMC) oversees assessment before this. Doctors who have trained overseas can take one of two paths to registration. Those who attained medical qualifications in selected countries (United Kingdom, United States, Canada, New Zealand and Ireland) can fast-track registration under a competent authority pathway. IMGs who obtained their medical accreditation in other countries follow a standard pathway.16 In the standard pathway, proficiency is assessed by a 3.5-hour, computer-based, multiple choice examination and an integrated multidisciplinary structured clinical assessment. Clinical skills in medicine, surgery, obstetrics, gynaecology, paediatrics and psychiatry are assessed at 16 stations using role-players and one or two real patients. Candidates have 2 minutes of reading time and 8 minutes to complete the task at each station. A pass requires satisfactory performance in 12 or more stations, including one obstetrics and gynaecology station and one paediatrics station.

The waiting period to sit for the structured clinical assessment is long, and often fewer than half of the candidates are successful.9,17 Combined with a low pass rate, this restricts employment and subsequent opportunities for many IMGs. From an IMG’s perspective, the traditional examinations provide a very limited opportunity to understand and be integrated into the Australian health care system.

Evidence suggests that this traditional pathway for registering and integrating IMGs into the Australian health care system has not been ideal. A recent study found that IMGs are more likely than Australian-trained doctors to have complaints made against them to medical boards.18 The medical boards in Australia have also been more likely to make adverse findings against IMGs than against Australian-trained doctors.18 The authors of this study suggested a rethink on the regulation of IMGs in Australia. A logical starting place for reviewing this would be at the start of the IMGs’ journey.

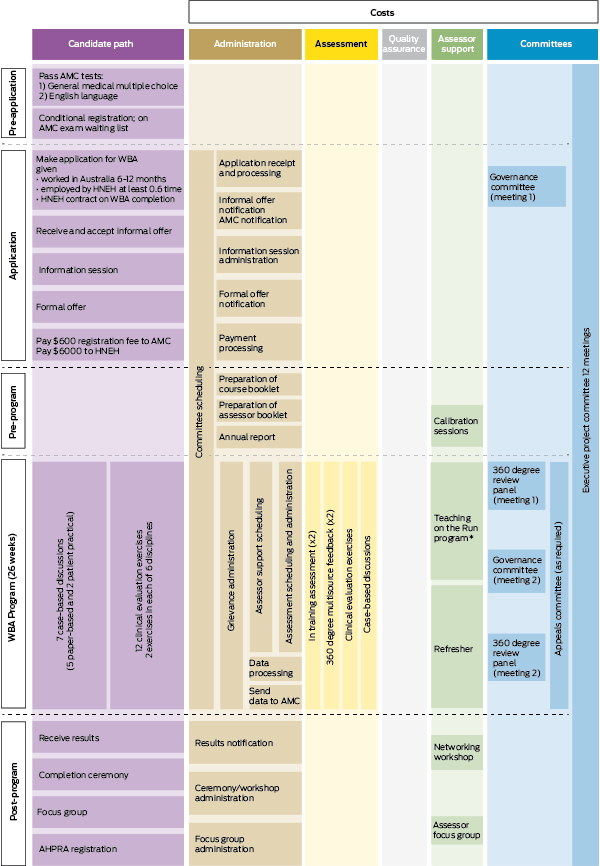

The Workplace Based Assessment (WBA) Program was developed in 2010 by a team of academics from Hunter New England Health (HNEH) and the University of Newcastle (UN) to overcome some of the difficulties associated with assessing IMGs and integrating them into the health care system. It was accredited by the AMC in 2010 as an alternative to the AMC clinical examination and to give an opportunity to study its feasibility. The WBA Program is based on a 6-month assessment process. Entry into the WBA Program has the same eligibility requirements as the standard pathway, including verification of qualifications and passes in the AMC English language test and the multiple choice exam. However, the WBA candidates have limited medical registration to work in accredited Australian hospitals.9 Details of the program have been reported previously,17 and are summarised in Box 1. A recent parliamentary enquiry recommended a national rollout.9

Health system resources provided by HNEH and UN to deliver the program include:

91 assessors from medicine, surgery, paediatrics, obstetrics and gynaecology, mental health, emergency and general practice;

academics to conduct calibration and recalibration of assessors;

administrative staff to support and coordinate the program;

staff members for the program committees (governance committee; appeals committee; 360° review panel); and

the Director of the program.

We assessed 2012 costs by stipulating:

the resources considered appropriate for inclusion in the costing;

the measurement of these resources;

how monetary units were applied.19

The measurement of the quantity of resources relied on a mapped pathway of the program (Box 2). The map identified five major stages of activity. Other sources included administrative documents, interviews with recent candidates, staff and assessors and observation of induction and feedback sessions.

Monetary values, in Australian dollars, were applied to the quantity of resources used in the delivery of the WBA Program. We aimed to base costs on opportunity cost, which is the value of activity forgone because of the resources committed to the program. Market price is an appropriate proxy for the opportunity cost of the resource.20 Four levels of labour were recognised (Box 3):

Administrative activities of a health manager.21

Administrative activities in support roles (eg, support at workshops such as the information session and graduation), costed as administration officers.22

Clinicians providing assessment, feedback, involvement with committees etc, costed as staff specialists.23

Executive staff providing services for assessments, feedback, time on committees, governance and presentations at workshops, costed as senior staff specialists plus a special academic allowance.23

The analysis allowed for the examination of cost by program stage, cross-tabulated by activity (Box 4). The most resource-intensive stage was program delivery ($190 566). Of this amount, $176 027 was for assessment. Major cost components for assessment were mini clinical evaluation exercises ($122 691) and case-based discussions ($43 396).

Projections indicate that the supply of doctors in Australia is likely to fall short of demand until at least 2025, suggesting IMGs will remain an important source of skilled clinicians in this country.24 The WBA Program can be delivered in regional Australia (where there are substantial doctor shortages). It makes good sense to ensure that IMGs seeking registration in Australia are provided with an efficient and fair opportunity to register.

1 Outline of the pathway for international medical graduates in the Workplace Based Assessment Program*17

Received 24 June 2013, accepted 19 August 2013

- Balakrishnan (Kichu) R Nair1,2

- Andrew M Searles3

- Rod I Ling3

- Julie Wein1

- Kathy Ingham1

- 1 Centre for Medical Professional Development, Hunter New England Local Health District, Newcastle, NSW.

- 2 School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW.

- 3 Hunter Medical Research Institute, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Birrell B. Too many GPs. Melbourne: Centre for Population and Urban Research, Monash University, 2013. http://artsonline.monash.edu. au/cpur/too-many-gps (accessed Sep 2013).

- 2. Australian Government Productivity Commission. Australia’s health workforce. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2005. http://www. pc.gov.au/projects/study/health-workforce/docs/finalreport (accessed Sep 2013).

- 3. Health Workforce Australia. Health workforce 2025: medical specialties. Vol. 3. Canberra: HWA, 2012. http://www.hwa.gov.au/sites/uploads/HW2025_V3_FinalReport20121109.pdf (accessed Sep 2013).

- 4. Birrel RJ. Australian policy on overseas-trained doctors. Med J Aust 2004; 181: 635-639. <MJA full text>

- 5. Bloor K, Hendry V, Maynard A. Do we need more doctors? J R Soc Med 2006; 99: 281-287.

- 6. Buchan JM, Naccarella L, Brooks PM. Is health workforce sustainability in Australia and New Zealand a realistic policy goal? Aust Health Rev 2011; 35: 152-155.

- 7. Gorman DF, Brooks PM. On solutions to the shortage of doctors in Australia and New Zealand. Med J Aust 2009; 190: 152-156. <MJA full text>

- 8. Harris MF, Zwar NA, Walker CF, Knight SM. Strategic approaches to the development of Australia’s future primary care workforce. Med J Aust 2011; 194: S88-S91. <MJA full text>

- 9. House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health and Ageing. Lost in the labyrinth: report on the inquiry into registration processes and support for overseas trained doctors. Canberra: Parliament of Australia, 2012. http://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/house_of_representatives_committees?url=haa/overseasdoctors/report.htm (accessed Sep 2013).

- 10. Iredale R. Luring overseas trained doctors to Australia: issues of training, regulating and trading. Int Migr 2009; 47: 31-65. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00563.x.

- 11. Joyce CM, McNeil JJ. Participation in the workforce by Australian medical graduates. Med Educ 2006; 40: 333-339.

- 12. Kamalakanthan A, Jackson S. The supply of doctors in Australia: is there a shortage? Discussion paper no. 341. Brisbane: School of Economics, University of Queensland, Queensland, 2006. http://www.uq.edu.au/economics/abstract/341.pdf (accessed Sep 2013).

- 13. Kamalakanthan A, Jackson S. Doctor supply in Australia: rural–urban imbalances and regulated supply. Aust J Prim Health 2009; 15: 3-8. doi: 10.1071/PY08055.

- 14. Maynard A. Medical workforce planning: some forecasting challenges. Aust Econ Rev 2006; 39: 323-329. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8462.2006.00422.x.

- 15. Schofield DJ, Fletcher SL, Callander EJ. Ageing medical workforce in Australia – where will the medical educators come from? Hum Resour Health 2009; 7: 82.

- 16. Medical Board of Australia. International medical graduates. Standard pathway. http://www. medicalboard.gov.au/Registration/International-Medical-Graduates/Standard-Pathway.aspx (accessed Apr 2013).

- 17. Nair BR, Hensley MJ, Parvathy MS, et al. A systematic approach to workplace-based assessment for international medical graduates. Med J Aust 2012; 196: 399-402. <MJA full text>

- 18. Elkin K, Spittal MJ, Studdert DM. Risks of complaints and adverse disciplinary findings against international medical graduates in Victoria and Western Australia. Med J Aust 2012; 197: 448-452. <MJA full text>

- 19. Evans C, Crawford B. Direct medical costing for economic evaluations: methodologies and impact on study validity. Drug Inf J 2000; 34: 173-184.

- 20. Drummond MF, O’Brien B, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW, editors. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- 21. Industrial Relations Commission of New South Wales. Health Managers (State) Award. 27 July 2012. (Publication No. C7866.)

- 22. Industrial Relations Commission of New South Wales. Health Employees’ Administrative Staff (State) Award. 27 July 2012. (Publication No. C7873.)

- 23. Industrial Relations Commission of New South Wales. Staff Specialists (State) Award. 5 October 2012. (Publication No. C7975.)

- 24. Health Workforce Australia. Health workforce 2025: doctors, nurses and midwives. Vol. 1. Canberra: HWA, 2012. http://www.hwa.gov.au/sites/uploads/FinalReport_Volume1_FINAL-20120424.pdf (accessed Sep 2013).

Abstract

Objective: To estimate the cost of resources required to deliver a program to assess international medical graduates (IMGs) in Newcastle, Australia, known as the Workplace Based Assessment (WBA) Program.

Design and setting: A costing study to identify and evaluate the resources required and the overheads of delivering the program for a cohort of 15 IMGs, based on costs in 2012.

Main outcome measures: Labour-related costs.

Results: The total cost in 2012 for delivering the program to a typical cohort of 15 candidates was $243 384. This equated to an average of $16 226 per IMG. After allowing for the fees paid by IMGs, the WBA Program had a deficit of $153 384, or $10 226 per candidate, which represents the contribution made by the health system.

Conclusion: The cost per candidate to the health system of this intensive WBA program for IMGs is small.