The case of Gloria Sam, which occurred in Sydney, came before the courts in 2009 and 2011.1,2 Gloria, a child, presented with her parents to general practitioners for medical treatment on several instances over an extended period with atopic dermatitis (AD), but her parents did not follow through with recommended medical advice or with referrals to dermatologists. The child’s father, a complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practitioner, administered homeopathic remedies, which usually contain no or almost no molecules of the original substance.3 The child finally presented to hospital and died as a result of overwhelming sepsis from secondarily infected atopic dermatitis.

This case was judged to constitute a case of child abuse. The father’s homeopathic treatment of his daughter was also assessed and he was found culpable under the “reasonable parent” test and the “reasonable homeopath” test, on the basis that a “reasonable homeopath” would have referred non-improving patients to conventional medical assessment for treatment.1

This tragic case represents an extreme end of the spectrum of neglect due to alternative health beliefs. However, lesser cases fuelled by parental fear of using topical corticosteroid (TCS) are a constant problem for dermatologists.4

AD is the most common paediatric dermatological condition worldwide and, with appropriate TCS treatment, is generally easily managed. Poorly controlled AD is disabling and disruptive for patients and their families.4-7 Poor adherence to treatment frequently results in unsatisfactory outcomes.5,6,8

The fear of using TCS, usually called “corticosteroid phobia”, is a frequent concern expressed by between 40% and 73% of dermatology patients and parents,9-12 and is a major cause of treatment non-adherence and failure in AD.9,13-15 This fear is likely to result in parents withholding TCS treatment from their child in some cases, although more research is required to quantify this phenomenon. Non-adherence to treatment is also seen by paediatricians attempting to manage asthma with inhaled corticosteroids.4,9,13,14

TCS is accepted as the gold-standard treatment for AD in dermatology and has very few side effects if correctly used. However, Australian parents commonly believe that medical treatment for AD with TCS is dangerous and that “natural” therapy is safe and therefore preferable.4 Parents often state that the danger associated with the use of TCS is that it will thin the skin irreversibly. However, this belief stems from cases where skin damage has occurred in the context of inappropriate TCS use outside of a supervised treatment program. Many parents also voice concerns about immune suppression and growth failure, but there is no evidence for this happening.

CAM is commonly used by parents to treat their children’s AD.16,17 Reasons include a desire to find a lasting cure and a fear of medical treatments with side effects. Parents often experience guilt and feelings of failure in relation to their child’s AD.4 The desire to find an external cause for their child’s condition may result in a focus on allergy and probably also explains some parents’ relentless search for this “external” cause, despite intellectually appreciating the genetic basis of AD.

Parents often prefer to commence treatment with something “natural” and move on to TCS only when the AD is very severe.4 Further, it is not unusual for parents to seek CAM therapies concurrently with conventional medical opinions, resulting in increased financial burden and conflicting advice. Despite often being unable to precisely define what natural treatments are, parents still believe that such products are safer and have fewer side effects than TCS. Parents rarely possess a comprehensive understanding of regulatory controls for medicines, including safety testing.18

Child maltreatment of all forms, especially neglect, can be difficult to detect, particularly when parents deliberately mislead medical professionals. They may do this with intent to defy medical advice, out of pride or out of fear of prosecution.19

Conflicts between parents’ health beliefs and their child’s health needs present significant ethical challenges to medical practitioners. In rare cases, the law can be used to enforce treatment — for example, to enforce use of blood products in the children of Jehovah’s Witnesses.20,21 For medical practitioners managing conditions such as AD, asthma and juvenile chronic arthritis, increasingly frequent community questioning and fear of Western conventional medicine raises adherence issues that may require intervention.

A medical practitioner who has reason to believe that parents’ health beliefs or behaviour pose a risk to a child’s wellbeing is ethically and legally obliged to act on this suspicion. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child requires children to be protected against abuse and to be afforded adequate standards of living for physical and psychological development22 — a view upheld by all Australian jurisdictions. In our opinion, this would include intervening in situations where parents or others impinge on the child’s right to freedom from physical and psychological pain and disability. For this reason, we argue that a medical practitioner faced with this situation may be ethically and morally obliged to make a formal report. The reporting requirements in each state and territory vary, so it is important to discuss the case with child protection professionals or refer to local statutory agency guidelines. The need to make this judgement, understandably, sits well outside the comfort zone of a medical practitioner. However, a key purpose of mandatory reporting of any suspected or actual instance of child abuse is to achieve better outcomes for children and families.

The case of Gloria Sam was extreme in its outcome but illustrates issues that are becoming increasingly common worldwide among parents of children with AD: rejection of treatment considered by medical practitioners to be safe and effective in favour of CAM,23,24 and restricted diets based on the belief that allergy causes the condition.3 While it is not clear whether corticosteroid phobia played a direct role in this particular case, it is certain that it influences many parents of children with AD. Targeted education of parents with children who suffer from AD to increase overall adherence may prevent less extreme cases.

It has been shown previously that multidisciplinary teams and support groups set up specifically around education and quality of life are successful in lowering anxiety in parents affected by AD.25,26 While these are useful adjuncts, parents have highlighted the importance of the trusted relationship with their medical practitioner.4,18,27 It is this relationship that forms the key platform for patient and parent education at the coalface of daily clinical practice.

Key suggestions from parents of children with AD on the best mechanisms for medical practitioners to engage and educate parents about treatment are summarised in Box 1 and Box 2.4 Parents can be reassured that recent research clearly shows the safety of TCS administered with a medically supervised treatment plan.28 Medical practitioners should not underestimate the impact of AD and should provide appropriate educational support. Further, despite the fact that food allergy occurs in up to 30% of children with AD,29 it can often be of limited clinical relevance to AD in many patients. However, a willingness to validate parental hopes by investigating food allergies will be seen as part of the support that parents look for from their medical practitioner, and parents seeking an allergy assessment for their child should be encouraged to consult a paediatric clinical immunologist. The beneficial effect of this tailored education will result in parents being empowered to withstand the many negative influences they encounter day-to-day.

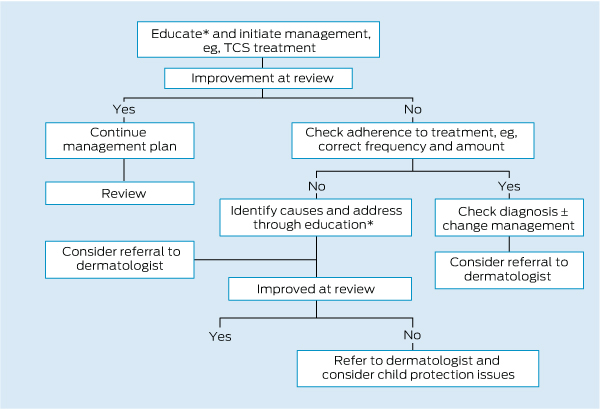

When education fails (Box 3), a decision regarding a report to a child protection authority is needed. A readiness to take this step where indicated and awareness of the correct procedures will hopefully prevent tragic cases such as the one described here, and cases of less severity but which still involve significant suffering.

1 Parents’ suggestions for medical practitioners*

Understand, respect and validate parental concerns

Do not dismiss the desire to investigate allergy

Alleviate guilt

Emphasise the positives: outcome, safety, prognosis

Encourage acceptance of “no cure”

Use your hospital

Re-educate pharmacists

Realise that parental trust in you is a major factor

Empower parents to withstand negative influences

Provide written and videotaped information that addresses parents’ fears

Encourage general practitioners to refer children with atopic dermatitis

2 Suggested information to increase parental confidence*

Safety data on TCS

Safety data on moisturisers

Information on relative potencies of prescribed TCS

Demonstration of use of TCS

Understanding of the concept of scientific testing

True role of allergy in AD

Explanation of how TCS works in AD

Possible outcomes of failure to treat

Importance of improving the child’s quality of life

AD = atopic dermatitis. TCS = topical corticosteroid. * Reproduced with permission.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Saxon D Smith1

- Amanda M Stephens2

- Julia C Werren3

- Gayle O Fischer4

- 1 Department of Dermatology, Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, NSW.

- 2 Westmead Hospital, Sydney, NSW.

- 3 School of Law, University of New England, Armidale, NSW.

- 4 Discipline of Dermatology, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. R v Thomas Sam; R v Manju Sam (No. 18) [2009] NSWSC 1003.

- 2. Thomas Sam v R; Manju Sam v R [2011] NSWCCA 36.

- 3. Schäfer T, Riehle A, Wichmann HE, Ring J. Alternative medicine in allergies – prevalence, pattern of use, and costs. Allergy 2002; 57: 694-700.

- 4. Smith SD, Hong E, Fearns S, et al. Corticosteroid phobia and other confounders in the treatment of childhood atopic dermatitis explored using parent focus groups. Australas J Dermatol 2010; 51: 168-174.

- 5. Cork MJ, Britton J, Butler L, et al. Comparison of parent knowledge, therapy utilization and severity of atopic eczema before and after explanation and demonstration of topical therapies by a specialist dermatology nurse. Br J Dermatol 2003; 149: 582-529.

- 6. Ben-Gashir MA, Seed PT, Hay RJ. Quality of life and disease severity are correlated in children with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2004; 150: 284-290.

- 7. Chamlin SL. The psychosocial burden of childhood atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther 2006; 19: 104-107.

- 8. Carroll CL, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR, et al. The burden of atopic dermatitis: impact on the patient, family, and society. Pediatr Dermatol 2005; 22: 192-199.

- 9. Charman CR, Morris AD, Williams HC. Topical corticosteroid phobia in patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol 2000; 142: 931-936.

- 10. Beattie PE, Lewis-Jones MS. A comparative study of impairment of quality of life in children with skin disease and children with other chronic childhood diseases. Br J Dermatol 2006; 155: 145-151.

- 11. Hon KL, Kam WY, Leung TF, et al. Steroid fears in children with eczema. Acta Paediatr 2006; 95: 1451-1455.

- 12. Ou HT, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. Understanding and improving treatment adherence in pediatric patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2010; 29: 137-140.

- 13. Fischer G. Compliance problems in paediatric atopic eczema. Australas J Dermatol 1996; 37 Suppl 1: S10-S13.

- 14. Skoner JD, Schaffner TJ, Schad CA, et al. Addressing steroid phobia: improving the risk-benefit ration with new agents. Allergy Asthma Proc 2008; 29: 358-364.

- 15. Brown KK, Rehmus WE, Kimball AB. Determining the relative importance of patient motivations for nonadherence to topical corticosteroid therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55: 607-613.

- 16. Hughes R, Ward D, Tobin AM, et al. The use of alternative medicine in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol 2007; 24: 118-120.

- 17. Johnston GA, Bilbao RM, Graham-Brown RA. The use of complementary medicine in children with atopic dermatitis in secondary care in Leicester. Br J Dermatol 2003; 149: 566-571.

- 18. Ruzicka T. Atopic eczema between rationality and irrationality. Arch Dermatol 1998; 134: 1462-1469.

- 19. Winterton PM. Child protection and the health professional: mandatory responding is our duty. Med J Aust 2009; 191: 246-247. <MJA full text>

- 20. Re T (Adult) [1992] 4 All ER 649.

- 21. Malette v Shulman (1990), 67 DLR (4th).

- 22. United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. New York: United Nations, 1989. http://www.unicef.org.uk/UNICEFs-Work/Our-mission/UN-Convention (accessed Sep 2012).

- 23. Lam J, Friedlander SF. Atopic dermatitis: a review of recent advances in the rield. Pediatr Health 2008; 2: 733-747. doi: 10.2217/17455111.2.6.733.

- 24. Su JC, Kemp AS, Varigos GA, Nolan TM. Atopic eczema: its impact on the family and financial cost. Arch Dis Child 1997; 76: 159-162.

- 25. Ricci G, Bendandi B, Aiazzi R, et al. Three years of Italian experience of an educational program for parents of young children affected by atopic dermatitis: improving knowledge produces lower anxiety levels in parents of children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol 2009; 26: 1-5.

- 26. Weber MB, Fontes Neto Pde T, Prati C, et al. Improvement of pruritus and quality of life of children with atopic dermatitis and their families after joining support groups. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008; 22: 992-997.

- 27. Ohya Y, Williams H, Steptoe A, et al. Psychosocial factors and adherence to treatment advice in childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2001; 117: 852-857.

- 28. Hong E, Smith S, Fischer G. Evaluation of the atrophogenic potential of topical corticosteroids in pediatric dermatology patients. Pediatr Dermatol 2011; 28: 393-396.

- 29. Katelaris CH, Peake JE. 5. Allergy and the skin: eczema and chronic urticaria. Med J Aust 2006; 185: 517-522. <MJA full text>

Summary

The gold standard for treatment of atopic dermatitis is topical corticosteroids.

Parental alternative health beliefs and fear of topical corticosteroids may lead to non-adherence and treatment failure.

At the extreme end, such beliefs may result in neglect constituting reportable child maltreatment.

We examine the legal repercussions of such abuse in the criminal case resulting from the death of Gloria Sam.