More than 50% of students now entering medical school are female; in 2012, of the 3600 graduates across Australia 55% were women.1 The vast majority of these are now in the medical workforce and most will wish to undergo some form of further training in the near future.2,3 For those undertaking training to fulfil the requirements of one of the increasing number of specialist colleges, this may mean up to 8 years of further training. Training to become a Fellow of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) takes a minimum of 6 years; completing subspecialty training (eg, maternal fetal medicine) requires at least another year. In 2012 and 2013, 80% of young doctors commencing Fellowship training were women (RANZCOG Workforce and Evaluation Unit, unpublished data).

Most of those completing the medical course do so in their mid twenties to early thirties; post-graduate training therefore most commonly takes place between the ages of 25 and 35. This is exactly the age group which, as obstetricians, we see as the optimal time for women to undertake pregnancy and childbirth. It is therefore unsurprising that a significant proportion of women undergoing specialist training wish to be able to take some time off from that training for pregnancy, birth and the care of their newborn infants. RANZCOG strongly supports women being able to access parental leave. However, while colleges such as RANZCOG oversee hospital appointments to ensure that the clinical exposure is sufficient for training, the colleges are not the employers. There is then the potential for an employer, for a number of reasons, not to provide women employees with ready access to parental leave and employment in a recognised training position on completion of that leave.

The realisation that the increasing feminisation of the specialist obstetric and gynaecological workforce might have significant implications for training positions, and some anecdotal reports of difficulties with parental leave, led to RANZCOG's decision to conduct an anonymous online survey of all current trainees and of those who had recently gained their Fellowship. The purpose of the survey was to ascertain the experience of participants, both male and female, of parental leave. While we were particularly interested in the results from the point of view of developing and improving our own college policies, we believe that our findings could have implications for other specialist colleges and training institutions, since the feminisation of the workforce extends into every discipline.

Methods

The parental leave survey was developed and piloted by three of us (C de C, L F, A C) in conjunction with members of the RANZCOG Board and about 20 RANZCOG Fellows and trainees. The survey was administered with SurveyMonkey between 16 August 2012 and 14 September 2012, and emailed to trainees and Fellows who had graduated within the previous 6 years. Approval for the study was given by the Women's Health Committee and the Board of RANZCOG; it was not considered necessary to apply for separate ethics approval for this study. Participants were regarded as consenting if they decided to take part in the survey after reading the introductory information provided. SurveyMonkey and QuickCalcs (GraphPad Software) were used to analyse quantitative data, and thematic analysis was applied to free text comments. The Fisher exact test was used to examine differences between male and female participants' responses to questions about the effects of parental leave taken by trainee colleagues on participants' own training.

The survey questionnaire (Appendix) was constructed in two parts. Part A focused on demographic information and general views about parental leave and its impact on wider work units. Part B applied only to respondents who indicated that they had taken parental leave during training. All respondents to part B were women.

The survey was designed to gather information relating to:

- the general impact of parental leave on those continuing to work in training units when fellow trainees have taken leave;

- the number of times individual trainees request parental leave;

- the length of parental leave taken;

- participants' perceptions of College-wide views about those requesting parental leave; and

- the impact that a pregnancy and subsequent request for parental leave may have on employment and re-employment opportunities for the trainee.

Results

There were 1051 eligible participants invited to take part in the survey: 596 trainees (both active and on leave) and 455 recently graduated Fellows; of these, 261 (24.8%) responded. Box 1 shows the sex of trainees and Fellows invited to take part and of those responding to the survey. Overall, 206 women (78.9%) and 55 men (21.1%) responded. Box 2 shows a breakdown of trainees and Fellows by year of training or year of graduation to Fellowship. Among trainees who responded, percentages of men and women were comparable to those among invitees, but among responding Fellows, the percentage of men was lower.

Most of the respondents (220; 84.3%) were aged 40 years or less; 194 (74.3%) were aged between 30 and 40 years.

Overall, 162 (62.1%) of responses came from trainees and 99 (37.9%) from Fellows. When asked if they had taken parental leave during training, 115 (44.1%) said they had, 137 (52.5%) had not, and nine (3.4%) did not answer the question. There were 107 participants (41.0%) who said they had taken parental leave and who responded to Part B.

All trainees are required to have a RANZCOG email address and no emails were returned undelivered. Fellows are requested to update email addresses annually; however, a small number of Fellows' emails were returned undelivered.

Respondents who had taken parental leave

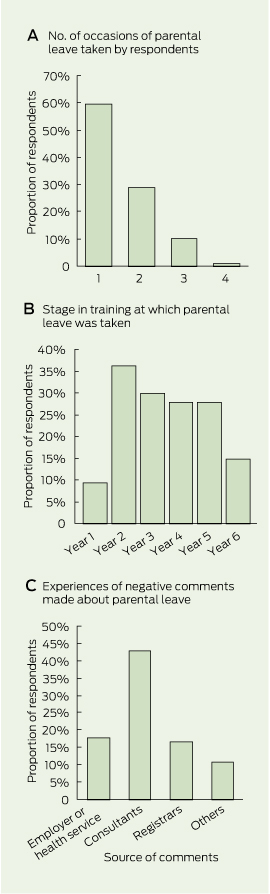

Respondents to Part B were asked on how many occasions they had taken parental leave (Box 3, A). Of the 115 who had taken leave, 107 answered questions about how much leave had been taken, and whether they had any difficulties accessing leave. Of those, 64 (59.8%) had taken leave on one occasion only, and 68 (63.6%) had taken 6 months or less. (Box 3, B) shows the stage in training at which respondents took parental leave.

When asked whether leave was granted automatically on application, 100 (93.5%) said it was, and seven (6.5%) said it was not. Four respondents (3.7%) had their applications for leave refused.

Among female respondents who had taken parental leave, 28 (26.2%) reported they had been asked about their intentions regarding future pregnancy by a prospective employer in the course of a job application, and 79 (73.8%) had not. Responses to the question, “Have you experienced negative comments about your parental leave from registrars, consultants or employers?” are shown in (Box 3, C). Forty-five respondents (42.1%) reported experiencing negative comments from consultants, and significant proportions reported negative comments from employers and registrar colleagues.

When asked about return to employment after parental leave, 14 respondents (13.1%) reported experiencing difficulties and 93 (86.9%) did not, and 11 (10.3%) reported experiencing difficulty obtaining a college-approved training post on their return from parental leave.

Impact of parental leave on other trainees

Responses to the question “Have you ever felt inconvenienced by another trainee in the program taking leave from the same service?” are shown in (Box 4). These concern inconvenience experienced by registrars when another trainee in the program took parental leave, including adverse changes to recreational or other leave and adverse roster changes. Significant numbers of both male and female respondents reported being inconvenienced, but in all responses the proportion of men who felt affected was much higher than that of women. Free text comments were analysed thematically with regard to whether they were made about registrars, consultants or employers, and whether they were concerned with rostering or recreational leave. A representative selection of six comments of a total 47 is included in (Box 5).

Discussion

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution given the relatively low number of respondents, particularly since those who felt they had been adversely affected may have been more likely to participate, and since among Fellows there was a higher proportion of female than male respondents. However, it can be concluded that there is a substantial pool of trainees and recent trainees with difficulties relating to their own parental leave or that of trainee colleagues.

Trainees were nearly always able to access parental leave automatically in all years of training, but some did have difficulty finding a suitable vacant training position when they returned to work. Although the employer is legally obliged to find an equivalent position when an employee returns to work, in reality, the position has often been filled by another trainee who may then be understandably reluctant to vacate it. One possible solution is to have a pool of “service registrars” who can meet the service needs of the hospital while a trainee is on parental leave but who have no need to continue the training after this period.

Difficulties experienced by other trainees as a result of a colleague's parental leave are numerically significant. With 80% of new trainees being women, parental leave must be regarded as an integral part of the training program, and employers need to develop strategies to ensure service requirements can be met without impacting adversely on those registrars remaining in the health service. Where trainee numbers are large, the impact of a single trainee leaving is likely to be proportionately less. However, in smaller hospitals, the departure of a trainee may have very substantial rostering effects on those remaining. The significantly higher proportion of male trainees who reported being disadvantaged by colleagues taking parental leave is concerning. Even if this disadvantage was more perceived than real, it is a finding that emphasises the need for changes in workforce planning to incorporate parental leave into training programs.

Equally of concern are the 42.1% of women taking parental leave who reported experiencing negative comments about their leave, and the 26.2% who reported being questioned about their intentions for future pregnancies in relation to job interviews. The free text responses to these questions also indicate that respondents saw verbal criticism from both consultants and registrars as a significant issue. It would appear that an educational process is required among professional colleagues at all levels. To some extent, it would be more productive if such comments were directed to the health service if it has failed to establish systems to replace women taking parental leave. The trainee herself cannot be responsible for correcting these deficiencies, and open negativity is both unhelpful and unprofessional.

Parental leave is an integral and important component of specialist training for all medical colleges. The complexity of administrative arrangements is increased by the fact that the colleges define the training programs, yet do not have control over employment and its conditions. Although the colleges do not have the ability to direct employers, they may still be held responsible by a trainee for industrial matters between employers and employees. In all jurisdictions, employers have industrial obligations around parental leave, and trainees need to be aware of their industrial rights if employment difficulties arise.

It is essential that potential deficiencies in parental leave provision are addressed, and educative processes established within the health services, to enable women to stay in the workforce, and to encourage young women graduates to pursue postgraduate training.

1 Survey participants by FRANZCOG status and sex

Career status and sex | Respondents (n = 261) | Invitees (n = 1051) | |||||||||||||

Trainees | |||||||||||||||

Male | 30 (11.5%) | 144 (13.7%) | |||||||||||||

Female | 132 (50.6%) | 452 (43.0%) | |||||||||||||

Fellows | |||||||||||||||

Male | 25 (9.6%) | 195 (18.6%) | |||||||||||||

Female | 74 (28.4%) | 260 (24.7%) | |||||||||||||

FRANZCOG = Fellow of the Royal Australian and of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. | |||||||||||||||

2 Survey participants by FRANZCOG status and career stage

Career stage | Respondents (% female) | Invitees (% female) | |||||||||||||

Trainees by year | |||||||||||||||

Year 1 | 17 (82.4%) | 127 (76.4%) | |||||||||||||

Year 2 | 32(84.4%) | 88 (83.0%) | |||||||||||||

Year 3 | 31 (90.3%) | 77(81.8%) | |||||||||||||

Year 4 | 33 (75.8%) | 61 (75.4%) | |||||||||||||

Year 5 | 31 (80.6%) | 97 (64.9%) | |||||||||||||

Year 6* | 18 (72.2%) | 146 (68.5%) | |||||||||||||

Fellows by graduation year | |||||||||||||||

2007 | 19 (57.9%) | 73 (49.3%) | |||||||||||||

2008 | 11 (81.8%) | 71 (59.2%) | |||||||||||||

2009 | 19 (78.9%) | 69 (65.2%) | |||||||||||||

2010 | 14 (85.7%) | 92 (58.7%) | |||||||||||||

2011 | 21 (81.0%) | 96 (59.4%) | |||||||||||||

2012 | 15 (66.7%) | 54 (46.3%) | |||||||||||||

Total | 261 (78.9%) | 1051 (73.3%) | |||||||||||||

FRANZCOG = Fellow of the Royal Australian and of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. * Includes trainees who have done more than 6 years of training. | |||||||||||||||

4 Registrars' reported experiences related to their colleagues taking parental leave

Experiences reported by registrars | Men (n = 52) | Women (n = 200) | Total (n = 252) | P |

Felt inconvenienced by another trainee in the program taking parental leave from the same service | 29 (55.8%) | 36 (18.0%) | 65 (25.8%) | < 0.001 |

Experienced adverse roster changes (eg, more night shifts) as a result of another trainee in the program taking parental leave from the same service | 38 (73.1%) | 76 (38.0%) | 114 (45.2%) | < 0.001 |

Experienced adverse changes to recreational or other leave as a result of another trainee in the program taking parental leave from the same service | 24 (46.2%) | 37 (18.5%) | 61 (24.2%) | < 0.001 |

Received 14 March 2013, accepted 27 July 2013

- Caroline M de Costa1

- Michael Permezel2,3

- Louise M Farrell4

- Anne E Coffey1

- Ajay Rane5

- 1 James Cook University, Cairns, QLD.

- 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC.

- 3 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Melbourne, VIC.

- 4 King Edward Memorial Hospital, Perth, WA.

- 5 James Cook University, Townsville, QLD.

We are grateful to College House staff at RANZCOG for their assistance in preparing and administering the survey and collating data, and to Stephen Robson and Cindy Woods for assistance with writing up the study.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Kerin L. Not enough internships for medical graduates. ABC News AM [radio program transcript]. 23 Jul 2012. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-07-23/am-on-interns/4147274 (accessed Feb 2013).

- 2. Australian Medical Students' Association. National internship crisis updates. http://www.amsa.org.au/advocacy/internship-crisis/ (accessed Feb 2013).

- 3. Joyce CM, Stoelwinder JU, McNeil JJ, Piterman L. Riding the wave: current and emerging trends in graduates from Australian university medical schools. Med J Aust 2007; 186: 309-312.

Abstract

Objectives: To ascertain the views of trainees and recently graduated Fellows of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists on their experiences of taking parental leave during specialist training.

Design: An anonymous online survey, conducted over a 1-month period from 16 August 2012 to 14 September 2012, of participants' experiences of taking parental leave and of the effects of parental leave taken by trainee colleagues on participants' own training.

Setting and participants: All trainees undertaking training for the Fellowship of the College, and all Fellows who had graduated in the past 6 years were invited to take part. Of the total 1051 invitees, 261 responded to the survey.

Main outcome measures: Ease with which parental leave was granted, ability to return to a training post after taking leave, and participants' experiences of views expressed about parental leave in the work environment.

Results: Most participants requesting parental leave were able to access it and return to a training post; however, a small proportion experienced difficulties. Among female respondents who had taken parental leave, 28 (26.2%) reported being asked about their intentions for future pregnancy during the training application process, and 45 (42.1%) reported receiving negative comments about this in the work environment.

Conclusions: While in most instances parental leave is accessible automatically, a small but significant number of trainees reported encountering difficulties. These matters are being addressed within our own College, and our results are likely to be relevant to all bodies involved in postgraduate medical training, particularly given the increasing feminisation of the medical workforce.