A brief examination that focuses on detecting major neurological deficits enables rapid identification of the location and severity of any stroke. The most widely used structured grading system for assessing the severity of neurological deficit in the setting of acute stroke is the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). Assessment using the NIHSS takes less than 2 minutes, requires none of the paraphernalia of a full neurological examination (which is unnecessary in this situation) and is highly predictive of both short-term (in-hospital) and medium-term (at-home) functional outcomes (grade A evidence).1 Skilled use of the NIHSS requires only a few hours of training and accreditation (see http://www.americanheart.org and http://learn.heart.org/ihtml/application/student/interface.heart2/nihss.html). The NIHSS includes a useful grading system for limb paresis that is based on “limb drift”, which overcomes limitations of the traditional UK Medical Research Council grading system for muscle strength (0 for no movement to 5 for normal strength). The NIHSS assessment of limb strength requires the patient to raise an arm or leg off the bed. If he or she can raise it completely off the bed and hold it steady for 10 seconds, limb strength is considered normal and is scored 0. If drift is noticed but the limb can be kept off the bed throughout, a score of 1 is given. If the limb falls to the bed within 10 seconds, a score of 2 is given. Inability to overcome gravity scores 3, and no movement of the limb scores 4. If the patient is unable to adequately obey commands, the observation of spontaneous movement or drift (rapid return to the bed) after the assessor lifts the patient’s limb in the air can allow adequate assessment of motor function.

Clinically, Catherine had had a significant stroke and was within the time window for considering thrombolysis, so the next step was an urgent computed tomography (CT) scan to rule out haemorrhage. It is not uncommon to find no acute ischaemic changes on an initial CT scan in patients who have had an acute stroke because visible ischaemic changes usually lag several hours behind what is actually happening in the cerebral tissue. While magnetic resonance imaging can detect early cerebral ischaemia, this is less readily available than CT scanning for urgent cases in hospitals. New software that enables advanced multimodal CT imaging in patients who are being considered for thrombolysis is gaining popularity in assisting clinicians in their decision making regarding the use of thrombolysis (grade C evidence).2,3

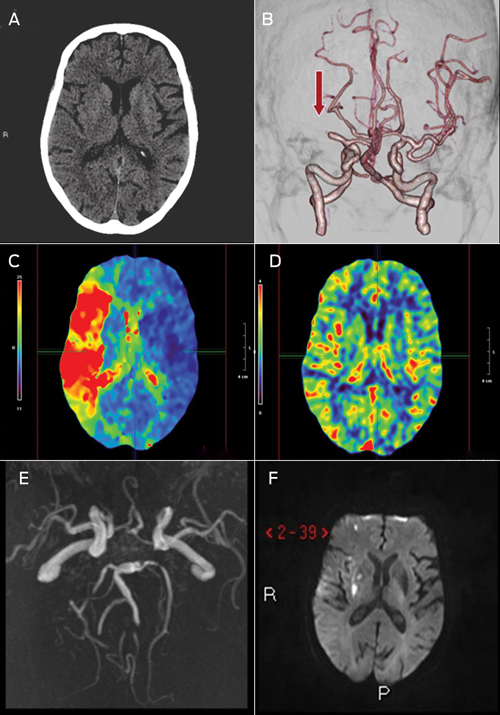

After Catherine’s initial clinical assessment, she proceeded to non-contrast CT of her head, which showed no acute ischaemic changes. Perfusion CT (CTP) and CT angiogram (CTA) were then carried out, which confirmed that she had a mid-M1 segment occlusion of the right middle cerebral artery. Despite minimal infarcted cerebral tissue, the whole of the middle cerebral artery territory was at risk (ie, there was an ischaemic penumbra) (Box 1).

In contrast, minor strokes can be subtle neurological events that may stutter or evolve over hours or days (Box 2). Thus without a history of sudden onset (from the patient or a reliable witness) and/or the presence of atypical, “positive” or inconsistent features, the likelihood of an underlying alternative diagnosis (ie, stroke mimic) is increased (Box 3). In the past, a cut-point of 24 hours was arbitrarily chosen as the duration of neurological symptoms used to separate the diagnosis of transient ischaemic attack from acute stroke in clinical and epidemiological research, but this is no longer clinically significant.

Most strokes (> 80%) are ischaemic and the remainder are due to haemorrhage, which can easily be differentiated on a non-contrast CT scan of the brain. Ischaemic stroke is caused by acute occlusion (clot) of an artery that leads to an immediate reduction in blood flow in the corresponding cerebrovascular territory. The size and site of the occlusion, and the efficiency of compensatory collateral blood flow, determine the extent of impaired blood flow and resulting neurological symptoms from at-risk brain tissue (the ischaemic penumbra [brain tissue that remains potentially salvageable but where blood supply is reduced to a level that unless restored will progress to infarction]) and/or dead brain tissue (the ischaemic core).4

Acute stroke can be treated rapidly and effectively in an ED with the basic clinical skills that all physicians have. This case highlights the crux of acute intervention in ischaemic stroke — reperfusion of the ischaemic penumbra.5 Intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) is the only treatment licensed by the TGA for treatment of ischaemic stroke, and in a substantial number of patients will result in effective dissolution of the clot.

There is compelling evidence to support the routine use of intravenous rtPA in patients with acute ischaemic stroke when carried out in experienced centres with adequate expertise available (grade A evidence).6

While the role of rtPA in acute ischaemic stroke has been debated, particularly within the emergency medicine community, current guidelines from the National Stroke Foundation (which are endorsed by the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine) and licensing by the Therapeutic Goods Administration reflect the evidence for use of rtPA up to 4.5 hours after symptom onset.7 Given that the chance of benefit is greatest when rtPA is used early, because ischaemia causes at-risk brain tissue to rapidly progress to irreversible infarction, the “time is brain” motto is most pertinent in defining systems of care for assessing patients who are potentially eligible for thrombolytic treatment. With a rapid chain of referral, thrombolysis rates of over 20% can be achieved (grade C evidence).8 Although there are risks of bleeding associated with rtPA, the most serious of which is intracerebral haemorrhage that is large enough to produce neurological deterioration, the risks and benefits, when given within the current time window, favours treatment, and this translates into one fewer patient dead or dependent for every 10 patients treated.6 Although the patient characteristics that predict the least to gain or the greatest hazard from rtPA have not been adequately defined, rtPA should be used with caution in certain situations (grade C evidence) (Box 4). It is clear that the benefit of rtPA is very much dependent on there being a clear time of onset of symptoms. This is not possible in up to one-fifth of patients. If a patient cannot provide a reliable history, then the onset of the stroke must be taken as the time when he or she was last seen well. This can be particularly challenging when the patient’s symptoms are present on waking (“wake-up stroke”), in which case the onset time must be taken as when he or she was last known to be well before going to sleep.

While inclusion and exclusion screening questionnaires are readily available for patients who are being considered for thrombolysis, the main practical issue of interest is an assessment of the risk of haemorrhage.7 Although blood tests, including tests of coagulation profile, are routinely undertaken for patients who have had a stroke, the results are usually normal in those who have previously been well and should not hold up the administration of rtPA (grade B evidence). However, in patients on warfarin therapy, rtPA should be avoided or used with caution if the international normalised ratio is above 1.7.7

Premorbid functioning is an important aspect of enquiry in older patients, as the balance of benefits and risks of thrombolysis is not as well defined in older patients as it is in younger adults. As such, clinicians can be presented with an ethical dilemma over the appropriate use of thrombolysis — a complex and risky treatment — in those older than 80 years.9 A global assessment of premorbid functioning can be made with specific enquiry regarding the patient’s ability to manage daily affairs, such as whether he or she is able to do his or her own shopping. Another useful guide of function is how long a family member would be prepared to leave the person on their own — for example, during the day or overnight. Age alone does not preclude the use (and potential benefits) of thrombolysis but an accurate assessment of premorbid functioning helps guide decision making (grade B evidence).7 As a general rule, patients of any age who have had a large “completed” stroke with large area of cerebral infarction before treatment do poorly irrespective of treatment.

When the neurology registrar enquired about Catherine’s premorbid functioning, her daughter described her as being independent in all daily activities, including shopping, and cognitively sharp without memory problems.

On review of Catherine’s eligibility for rtPA, she was found to be in AF, which had not been previously diagnosed. (Undiagnosed AF is not uncommon in patients who have had a stroke, because AF is often asymptomatic and intermittent before becoming persistent, with common triggers including alcohol intake, acute illness and obstructive sleep apnoea.) She had not been taking any antithrombotic treatment and had no history of bleeding. Her blood pressure was less than 185/110 mmHg (the cut-off for treatment with rtPA).

A “Lazarus-like” response such as this occurs in about one in 10 rtPA-treated patients; it results from there being minimal early infarction before treatment combined with early reperfusion of a large region of ischaemic brain. Thus, in the presence of a pattern of small infarct core and large ischaemic penumbra on advanced CT imaging (or magnetic resonance imaging), the Lazarus effect is quite common, although it is dependent on the rtPA being successful in rapidly dissolving the occlusive clot (grade C evidence).10

On review the next day, Catherine had no focal neurological deficit, and complete reperfusion and minimal infarction were shown on MRI (Box 1). She was commenced on long-term warfarin therapy. She was reviewed by allied health staff to check on her cognition, mobility and self-care activities, to ensure that it was safe for her to be discharged home. On Day 5, she was back to her premorbid level of functioning and was discharged.

Other proven interventions in the management of acute stroke include admission to and management in a stroke unit with the associated nursing and allied health expertise and, in patients with ischaemic stroke, commencement of aspirin therapy (100–150 mg daily) within 48 hours of symptom onset (grade A evidence).7 These should be considered for all patients who have had an ischaemic stroke, regardless of whether they are eligible for rtPA.

An outpatient stroke clinic allows the opportunity to: undertake outstanding investigations and review the results; check that patients are recovering satisfactorily, adjusting to residual disability, and adhering to lifestyle modifications (particularly cessation of smoking) and secondary stroke prevention strategies; review continuity of follow-up rehabilitation or support services; review communication with the patient’s general practitioner; check that the patient and his or her family have a reasonable understanding of stroke and its aetiology; and check that there are no major complications or comorbid consequences of the stroke event (Box 5).

1 Multimodal computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images of Catherine’s brain before and after treatment with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator

A: Non-contrast CT showing no acute changes, as is often the case in acute stroke.

2 Minor stroke syndromes that require particular attention in assessment

3 Common stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA) mimics, and features that may differentiate them from acute stroke and TIA

4 Situations where intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator should be used with caution

Large area of infarction on initial non-contrast computed tomography scan, indicating that time since onset is likely to be > 4.5 hours

Evidence of proximal vessel (terminal internal carotid [“carotid T”]) occlusion — in which case the patient may benefit from mechanical clot extraction procedures

Patient is older than 80 years

Patient is taking warfarin and has an international normalised ratio > 1.7, or is taking other therapeutic anticoagulants

Significant trauma from fall at time of stroke onset

5 Aspects of stroke that should be reviewed at a follow-up clinic

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Bill O’Brien1

- Mark W Parsons1

- Craig S Anderson2

- 1 Department of Neurology, John Hunter Hospital, Newcastle, NSW.

- 2 Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, NSW.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Kasner SE. Clinical interpretation and use of stroke scales. Lancet Neurol 2006; 5: 603-612.

- 2. Muir KW, Buchan A, von Kummer R, et al. Imaging of acute stroke. Lancet Neurol 2006; 5: 755-768.

- 3. Parsons MW. Perfusion CT: is it clinically useful? Int J Stroke 2008; 3: 41-50.

- 4. Donnan GA, Fisher M, Macleod M, Davis SM. Stroke. Lancet 2008; 371: 1612-1623.

- 5. Rha JH, Saver JL. The impact of recanalization on ischemic stroke outcome: a meta-analysis. Stroke 2007; 38: 967-973.

- 6. Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lancet 2010; 375: 1695-1703.

- 7. National Stroke Foundation. Clinical guidelines for stroke management 2010. Melbourne: NSF, 2010. http://www.strokefoundation.com.au/news/welcome/clinical-guidelines-for-acute-stroke-management (accessed Apr 2012).

- 8. Quain DA, Parsons MW, Loudfoot AR, et al. Improving access to acute stroke therapies: a controlled trial of organised pre-hospital and emergency care. Med J Aust 2008; 189: 429-433. <MJA full text>

- 9. Mishra NK, Ahmed N, Andersen G, et al. Thrombolysis in very elderly people: controlled comparison of SITS International Stroke Thrombolysis Registry and Virtual International Stroke Trials Archive. BMJ 2010; 341: c6046.

- 10. Parsons M, Spratt N, Bivard A, et al. A randomized trial of tenecteplase versus alteplase for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1099-1107.

Abstract

Stroke is a common neurological emergency and may occur in patients of all ages.

Rapid assessment is crucial for patients with acute neurological symptoms suggestive of stroke because the opportunity for a positive outcome from thrombolytic treatment diminishes rapidly within the first few hours.

Although plain non-contrast computed tomography of the brain is adequate to exclude haemorrhage and conditions such as malignancy, advanced multimodal imaging can be used to assist with decision making regarding the use of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and mechanical clot-retrieval approaches without adding significant delay.

Excellent outcomes are possible with the early use of reperfusion therapies, even when large areas of brain ischaemia are present, provided that there is evidence of potentially salvageable brain and that treatment can commence without unnecessary delay and hazard.