Acute cholecystitis secondary to gallstones is a common acute general surgical presentation. During early experience with laparoscopic cholecystectomy, acute cholecystitis was considered a contraindication.1 However, several studies showed that early cholecystectomy was safe.2-6 More recently, randomised controlled trials and a Cochrane review have shown that early cholecystectomy results in lower rates of morbidity, similar rates of conversion to open surgery, reduced hospital stay and lower economic cost when compared with delayed cholecystectomy.7-11

An acute surgical unit (ASU) was adopted by Nepean Hospital (a teaching hospital) in November 2006. The ASU is a novel consultant-led model of care for assessing and treating all patients who present with an acute general surgical condition.12 The ASU team consists of a consultant surgeon, two surgical registrars, two resident medical officers and a nurse practitioner working on a 12-hour shift (7 am to 7 pm). The consultant’s sole commitment during a shift is management of patients in the ASU. The team functions in the same way every day of the year, including weekends and public holidays. Overnight, there is a dedicated ASU registrar in the hospital and the consultant is on call. All patients who present with acute general surgical conditions or trauma are admitted into and stay under the care of the ASU. Patients with common conditions are managed according to agreed evidence-based best-practice protocols.

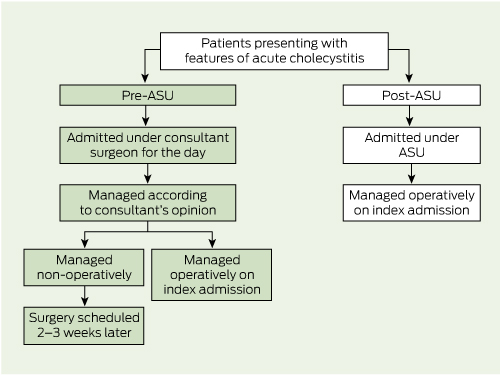

A retrospective study of medical records for patients presenting to Nepean Hospital with acute cholecystitis was conducted over a 4-year period (1 November 2004 to 30 October 2008) — the 2 years before and 2 years after introduction of the ASU (Box 1). The study was approved by the Sydney West Area Health Service Ethics Committee.

A total of 271 consecutive patients met the inclusion criteria; 114 presented before the ASU was introduced and 157 presented after. The key results are summarised in Box 2. The median age was 44.4 years (range, 14–85 years) in the pre-ASU group and 45.1 years (range, 14–89 years) in the post-ASU group (P = 0.01) and there were more females in both groups.

The ASU model also resulted in more rapid diagnosis and earlier surgery (3 days earlier in the admission on average). Although more patients had definitive surgery on index admission, the overall hospital stay was almost a day shorter. These improved efficiencies are due to the model being consultant-led and having a dedicated team available throughout the day to assess and treat patients. Another improvement in patient care was the increase in the proportion of patients who had surgery during daylight hours. Recent studies have highlighted that operating outside of daylight hours is associated with impairments in speed, accuracy and dexterity that contribute to potentially life-threatening errors.13-15

1 Management of patients with acute cholecystitis before and after introduction of an acute surgical unit (ASU) at Nepean Hospital

Received 25 October 2011, accepted 11 April 2012

- Lester Pepingco1

- Guy D Eslick2

- Michael R Cox2

- 1 Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, NSW.

- 2 Department of Surgery, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW.

Competing interests: No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Tompkins RK. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: threat or opportunity? Arch Surg 1990; 125: 1245.

- 2. Cox M, Wilson T, Luck A, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute inflammation of the gallbladder. Ann Surg 1993; 218: 630-634.

- 3. Jacobs M, Verdeja JC, Goldstein HS. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. J Laparoendosc Surg 1991; 1: 175-177.

- 4. Cuschieri A, Dubois F, Mouiel J. The European experience with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg 1991; 161: 385-387.

- 5. Peters JH, Gibbons GD, Innes JT, et al. Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery 1991; 110: 769-778.

- 6. Peters JH, Ellison EC, Innes JT, et al. Safety and efficacy of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A prospective analysis of 100 initial patients. Ann Surg 1991; 213: 3-12.

- 7. Keus F, de Jong JA, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ. Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (4): CD006231.

- 8. Lawrentschuk N, Hewitt P, Pritchard M. Elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: implications of prolonged waiting times for surgery. ANZ J Surg 2003; 73: 890-893.

- 9. Sobolev B, Mercer D, Brown P, et al. Risk of emergency admission while awaiting elective cholecystectomy. CMAJ 2003; 169: 662-665.

- 10. Lai P, Kwong K, Leung K, et al. Randomized trial of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 764-767.

- 11. Lo C, Liu C, Fan S, Lai E. Prospective randomised study of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg 1998; 227: 461-467.

- 12. Cox M, Cook L, Dobson J, et al. Acute surgical unit: a new model of care. ANZ J Surg 2010; 80: 419-424.

- 13. Grantcharov TP, Bardram L, Funch-Jensen P, Rosenberg J. Laparoscopic performance after one night on call in surgical department: prospective study. BMJ 2001; 323: 1222-1223.

- 14. Taffinder N, McManus I, Gul Y, et al. Effect of sleep deprivation on surgeons’ dexterity on laparoscopy simulator. Lancet 1998; 352: 1191.

- 15. Ricci WM, Gallagher B, Brandt A, et al. Is after-hours orthopaedic surgery associated with adverse outcomes? J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91: 2067-2072.

Abstract

Objective: To determine whether the introduction of an acute surgical unit (ASU) resulted in a greater proportion of patients with acute cholecystitis receiving definitive surgery on index admission with no adverse change in surgical outcomes.

Design, setting and participants: A retrospective study of medical records for patients presenting to Nepean Hospital with acute cholecystitis during the 2 years before and 2 years after introduction of an ASU in November 2006.

Main outcome measures: Time to diagnosis, timing of surgical intervention, surgical outcomes, duration of total admission and complication rates.

Results: A total 271 patients were included in the study (114 pre-ASU, 157 post-ASU). After introduction of the ASU, a higher proportion of patients had surgery on index admission (89.8% v 55.3%; P < 0.001) and there were decreases in median time to diagnosis (14.9 h v 10.8 h; P = 0.008), median time to definitive procedure (5.6 days v 2.1 days; P < 0.001), median duration of total admission (4.9 days v 4.0 days; P = 0.002), rate of intraoperative conversion to open surgery (14.9% v 4.5%; P = 0.003) and rate of postoperative infection (3.5% v 2.5%; P = 0.40).

Conclusion: Introduction of the ASU at Nepean Hospital resulted in significant improvements in care and outcomes for patients with acute cholecystitis.