Medical devices are ubiquitous in health care and have the potential to create large-scale health gains, but also unintended harms through device failure. In the United States in 2006, medical devices were responsible for 2712 deaths.1 The recall of DePuy Orthopaedics articular surface replacement hip prosthesis (Warsaw, Ind, USA) helped to highlight deficiencies in medical device regulation worldwide.2,3 Subsequent investigations in the US showed that most high-risk medical devices were being approved through processes that were not designed to assess safety or efficacy.4 Investigations into medical device regulatory processes in Europe were hampered by a lack of transparency and accountability.1

Medical device regulation is a complex and evolving area. Recently, a range of reports and reform proposals relevant to the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) have been put forward. A health technology assessment (HTA) tabled by the Department of Health and Ageing in December 2009 addressed “the regulatory burden on business that results from HTA processes”.5 After a consultation period, the TGA responded to this report in September 2011 by setting out proposals to reclassify joint-replacement implants, amend the manner in which devices are included on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) and increase the availability of device product information on the TGA website.6 In July 2011, the Department of Health and Ageing released a review that sought to increase the transparency of the TGA by improving communication in areas such as market authorisation processes and post-market monitoring and compliance, and through raising stakeholder involvement in the TGA.7 Subsequently, in November 2011, the Senate Standing Committees on Community Affairs released a report into the regulatory standards for the approval of medical devices in Australia, which made reference to most of the previous reports.8 In addition, this report made further recommendations related to the recalled DePuy Orthopaedics articular surface replacement hip prosthesis, inducements paid by device companies to clinicians, improved reporting of adverse events by clinicians and the importation of medical devices over the internet, among others.8 Finally, in December 2011, the TGA issued a document outlining their proposed changes in response to these reports, of which some changes related to medical devices.9

We only used publicly available sources of data — that is, information provided by the ARTG (https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/ANZTPAR/PublicWeb.nsf/cuDevices?OpenView [accessed 7 Jun 2011]) and information about medical device incidents that was provided on the TGA website (http://www.tga.gov.au/index.htm [accessed 24 Jan 2012]). Hence, ethics approval was not required for this study. We did not use information contained in medical device bulletins because they are not publicly accessible (only Australian health professionals currently working in a health care facility are allowed to subscribe to these after their application is approved by the TGA) and their use requires the permission of the TGA. All data extraction was conducted independently by R G M and T E R with consensus agreement.

The ARTG provides information on therapeutic goods that may legally be supplied in Australia. Each entry in the ARTG may provide information on one or more medical devices, with variants of a device included in a single entry. For example, two different-sized hip replacement prostheses may appear under the one entry. Each entry listed on the ARTG is classified by manufacturers and the TGA into one of several risk categories based on a series of algorithms.10 For example, low-risk devices include non-sterile dressings; low–medium-risk devices include contact lenses; medium–high-risk devices include infant incubators; and high-risk devices include permanent pacemakers. We used the ARTG website to determine the number and type of entries listed, which we used as a proxy for the number of medical devices available on the Australian market. However, because of the design of the ARTG website, with the potential for multiple devices within one entry, we were unable to count the true number of devices.

Data on incidents involving medical devices were unavailable for Jan 2000–Oct 2000, Jun 2002–Dec 2002, Jun 2003–Dec 2003, Jun 2004–Dec 2004 and Jul 2009–Dec 2011. In total, 6812 incidents were reported to the TGA and they have become more frequent over time (Box 1). It is unknown how many reports refer to the same medical device, as these data were not provided.

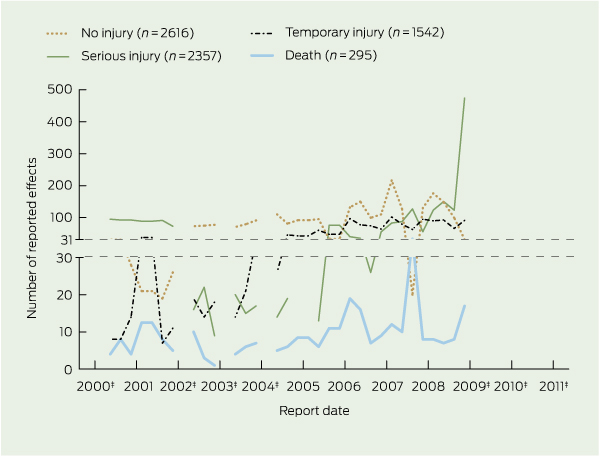

There were 295 reported deaths related to incidents involving medical devices, 2357 incidents associated with serious injury, 1542 incidents associated with temporary injury and 2616 incidents associated with no injury (Box 2). The number of serious injuries was highest in 2009 (597). Further information on what injuries were caused or how death occurred was unavailable on the website. The reported effect of the incident was not provided in two reports.

Incidents were often attributed to more than one cause, as 7644 causes were reported for 6812 incidents. While the cause of incidents involving medical devices was most often reported as “unknown”, the second most commonly reported cause, “mechanical” (13.0%), sharply increased towards the end of the study period, representing 32.8% (316/962) of all reports in 2009 (Box 3). Medical device sponsors reported the most incidents (56.5%). The source of incident reports was missing in 10 cases.

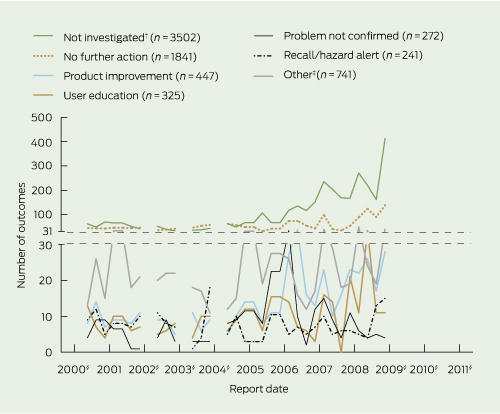

More than one outcome was often attributed to an incident, as there were 7369 outcomes for 6812 incidents. Most incident reports either were not investigated (47.5%), or were investigated but no further action was taken (25.0%). The proportion of incident reports not investigated increased in later years, from 41.1% (62/151) in 2000 to 59.5% (575/967) in 2009. Only 3.3% of reports resulted in a device recall or hazard alert, and 2.5% (187/7369) of reports in a safety alert being issued. The reported problem was unconfirmed for 3.7% of cases (Box 4). It is unknown how many incident reports were assigned more than one outcome, as these data were not provided.

Thirty-five device recalls were issued by the TGA (Box 1). There was no consistent increase in the number of device recalls over time. Twelve of these recalls were considered high risk, as the device had the potential to be life-threatening or cause a serious risk to health. For example, Four Seasons Glow’N’Dark Condoms (Australian Therapeutic Supplies, Sydney, Australia) were recalled in 2003 because they failed to meet performance standards. Nineteen of these recalls were considered medium risk, as the device had the potential to cause illness or mistreatment. For example, INVACARE Action 2000 wheelchairs (Invacare Australia, Sydney, Australia) were recalled in 2009 because of a fault that could have caused occupants to fall from their wheelchair and sustain injury. Four of these recalls were considered low risk, as the device did not pose a significant hazard to health. For example, Dejour tampons (Dejour Sanitary Products, Melbourne, Australia) were recalled in 2003 for failing to meet mandatory absorbency requirements.

Inconsistencies were found in the reported number of alerts issued by the TGA. An alphabetical list of all therapeutic alerts from January 2000 to December 2011 indicated there were 34 device-related alerts. The same list sorted by date indicated there were 33 device alerts issued. We cross-checked these lists, ensuring that each entry was only counted once, and found 34 unique device alerts (Box 1). Device alerts did not consistently increase over time.

Despite a series of reports urging transparency and reform, our investigation highlights a number of problems. First, it is unclear why there are several periods where data on incidents involving medical devices were unavailable, particularly as the number of serious injuries related to incidents increased towards the end of 2009. In addition, the data provided on alerts were inconsistent. Second, if the proportion of device problems investigated but not subsequently confirmed remained relatively constant, it is unclear why a growing number of incident reports were not investigated. If these “false alarms” remain constant, this implies that there may have been some validity to the incident report in the remaining cases, although this cannot be determined because so many reports remain uninvestigated. It may be that these incidents were not likely to lead to injury and so were not investigated. Third, it is unclear what class of device is being recalled. Current product recalls describe the level of risk presented by an incident, but not by the device itself. Fourth, it is unclear why reports of medical device incidents are consistently increasing while device recalls are not. In total, 295 deaths related to device incidents were reported, yet, during a longer observational period, there were only 12 “high-risk” medical device recalls. Increasing reports may reflect an increased awareness of the need to report all adverse events among the community — for example, through the establishment of the National Joint Replacement Registry. It may also reflect increased adherence of companies to their legal obligations, under sections 41MP and 41MPA of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cwlth), to report all adverse events.11

On the other hand, as the TGA website is updated and other proposals are implemented, some issues are likely to be resolved. For example, the TGA has now proposed a plan of action to reform the way in which medical devices are included in the ARTG.9 From July 2012, all ARTG entries for medical devices will be required to include product name details. This will facilitate the generation of a list of all the medical devices available on the Australian market. In addition, there are proposals to provide greater levels of device product information on the TGA website.9

While we have chosen to analyse data that are publicly available on the TGA website, this has led to a number of limitations. The data on medical device recalls, alerts and notifications are provided at a summary level, and so more advanced statistical analysis is not possible because data on individual devices are not provided. Because of the lack of up-to-date data, we were unable to determine whether the rise in the number of reported incidents involving medical devices was a random variation or the beginning of an increasing trend. In addition, we have not examined medical device bulletins or asked the TGA to provide further information. This is because we wanted to maintain the perspective of the average health care worker or informed consumer attempting to assess the safety and efficacy of a medical device. Finally, we could not locate data on the number of voluntary recalls issued by device manufacturers or the number of people affected by a recall because these data were not made public by the TGA.

Clearly, the demands being placed on the TGA are changing over time and the TGA is responding to these changes. While our primary concerns centre around the transparency of available data, the various government reports and TGA proposals have sometimes focused on other important but different issues; for example, the reclassification of prosthetic devices. None of the reports released to date or the reforms proposed by the TGA address the issues we have raised, namely missing and conflicting data, the increasing proportion of uninvestigated reports and a lack of information about the type of medical devices being recalled. The only reference to transparency in the Senate Standing Committees on Community Affairs report is the recommendation that “the Government implements the recommendations of the Therapeutic Goods Administration Transparency Review in a timely manner”.8 Of the 21 recommendations contained in the Department of Health and Ageing review on the transparency of the TGA, none specifically mention medical devices and none address the issues we have raised here. Nevertheless, the TGA’s recently released blueprint for reform does contain some constructive proposals — for example, including more information about individual medical devices on the TGA website. These efforts will go some way towards increasing transparency and allowing the public to have access to information that will help them to make informed decisions about safety and effectiveness.

1 Numbers of medical device recalls, alerts and incident reports,* January 2000–December 2011, and number of entries listing medical devices on the ARTG, 2011†

3 Most common sources of reports and reported causes for incidents involving medical devices,* January 2000 – December 2011

Received 30 September 2011, accepted 13 February 2012

- Richard G McGee1

- Angela C Webster2

- Thomas E Rogerson3

- Jonathan C Craig4

- Sydney School of Public Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW.

Jonathan Craig is a member of the Protocol Advisory Sub-committee of the Australian Medical Services Advisory Committee.

- 1. Heneghan C, Thompson M, Billingsley M, Cohen D. Medical-device recalls in the UK and the device-regulation process: retrospective review of safety notices and alerts. BMJ Open 2011; 1: e000155.

- 2. Cohen D. Out of joint: the story of the ASR. BMJ 2011; 342: d2905.

- 3. Graves SE. What is happening with hip replacement? Med J Aust 2011; 194: 1-2. <MJA full text>

- 4. Zuckerman D, Brown P, Nissen S. Medical device recalls and the FDA approval process. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171: 1006-1011.

- 5. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Review of health technology assessment in Australia, December 2009. Canberra: DoHA, 2009. http://www.health. gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/00E847C9D69395B9CA25768F007F589A/$File/hta-review-report.pdf (accessed Jan 2012).

- 6. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Reforms to the medical devices regulatory framework. Proposals. Canberra: TGA, 2011. http://www.tga.gov.au/newsroom/consult-devices-reforms-110923.htm (accessed Jan 2012).

- 7. Panel to Review the Transparency of the Therapeutic Goods Administration. Review to improve the transparency of the Therapeutic Goods Administration. Final report, June 2011. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2011. http://www.tga.gov.au/newsroom/review-tga-transparency-1101.htm (accessed Jan 2012).

- 8. Senate Standing Committees on Community Affairs. Inquiry into the regulatory standards for the approval of medical devices. Canberra: Parliament of Australia Senate, 2011. http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate_Committees?url=clac_ctte/medical_devices/report/index.htm (accessed Feb 2012).

- 9. Therapeutic Goods Administration. TGA reforms: a blueprint for TGA’s future. Canberra: TGA, 2011. http://www.tga.gov.au/newsroom/media-2011-tga-reforms-111208.htm (accessed Jan 2012).

- 10. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian regulatory guidelines for medical devices (ARGMD). Canberra: TGA, 2011. http://www.tga.gov.au/industry/devices-argmd.htm (accessed Jan 2012).

- 11. Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cwlth) (as amended). http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2011C00589/Html/Text#_Toc299972112 (accessed Jan 2012).

Abstract

Objective: To describe the frequency, characteristics and outcomes of reports of possible harms related to medical devices submitted to the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) using data made publicly available on the TGA website.

Design and setting: A retrospective analysis, conducted in January 2012, of data made publicly available on the TGA website from January 2000 to December 2011.

Main outcome measures: The number and nature of reports of medical device incidents, recalls and alerts.

Results: Up to December 2011, 6812 incidents involving medical devices were reported to the TGA, although there were several periods where data were unavailable. Incidents were reported more frequently in later years, most often by device sponsors, and were often attributed to mechanical problems. 295 deaths and 2357 serious injuries have been related to incidents, with serious injury (597) highest in 2009. Most incidents involving medical devices were not investigated (47.5%), or, after investigation, no further action was taken (25.0%). During the same time period, there were 35 medical device recalls and 34 medical device alerts issued by the TGA, with no consistent increase over time.

Conclusions: Despite TGA reform proposals, greater transparency is still needed. Issues that have not been addressed include patchy and conflicting data in the public domain and lack of explanations for the large proportion of uninvestigated reports. To maintain public confidence in the national regulatory system these problems need to be resolved.