Australia is well placed to reform its health sector to be more effective at promoting good health and managing lifestyle-related illness, chronic disease and an increasingly aged population. It has high standards of clinical care and training, strategies to deal with current health workforce shortage,1 and a relatively accessible primary care sector.2,3 However, many Australians find navigating a complex, rapidly changing and often impersonal health system increasingly difficult, and are thwarted in their search for the right care, at the right time, in the right place, from the right person.4 Consumers tell us that the road blocks between state- and Commonwealth-funded services are major sources of ongoing frustration and often significant danger.5 There is also growing evidence that confusion about state and Commonwealth funding causes significant waste and duplication.3

The National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission (NHHRC)6 has proposed an ambitious plan for Australia’s health care system, with no section more contentious than its proposed governance framework. In Chapter 6, the report states that, to “ensure Australia’s health system is sustainable, safe, fair and agile enough to respond to people’s changing health needs and a changing world, we need to make significant changes to the way it is governed”.6 It proposes two paths to be pursued concurrently — the first is the immediate introduction of the Healthy Australia Accord (HAA) and the second, a further 2 years of consultation and development around a competitive health and hospital planning framework for all Australians, called Medicare Select. Of the first path, the report states:

The first recommendation calls on all First Ministers to agree to a new Healthy Australia Accord that clearly articulates the agreed and complementary roles and responsibilities of all governments in improving health services and outcomes for all Australians. The Accord retains a governance model of shared responsibility for health care between the Commonwealth and state governments, but with . . . clearer accountabilities; better integrated primary health care . . . ; improved incentives for more efficient use of hospitals and specialist community based care . . . 6

It goes on to recommend a more unified system:

The Healthy Australia Accord would also shift the system towards ‘one health system’, identifying functions to be undertaken on a consistent national basis to improve quality, efficiency, fairness and sustainability.6

Here, we argue for a regional governance model that complements the HAA and translates well into the “bottom up” solution sought by the NHHRC. In its interim report, the NHHRC proposed a regional model — Option B.7 In its final report, it acknowledged that the “focus on local innovation and service delivery . . . should be an integral part of governance arrangements for Australia’s system that move beyond ‘top down’ reform proposed under the Health Agreement Accord”.6 However, it finally retreated from a regional option for several reasons: the risks of the Commonwealth government, inexperienced in health care, assuming the role of sole funder too quickly; difficulty in determining fair regional budgets and economies of scale; problems of cross-border movement of people; danger of inequities of access; and potential additional bureaucracy.6 Here, we answer these concerns by describing regional governance structures able to ensure the responsive, inclusive, appropriate health care delivery system that the NHHRC and all Australians seek.

A nationally defined framework able to administer consistent policies and standards is essential to better articulate intersectoral responsibility, integrate activity and enhance the quality and efficiency of care delivered across Australian health sectors. International experience suggests that consistent system-wide policies and standards are critical to achieving many health care reform outcomes. Primary care trusts in England allocate 80% of the National Health Service budget, based on an understanding of regional need.8 In Canada, local health integration networks, created by the Ontario government in 2006, work with local health providers and community members to determine health service priorities for their regions.9 Primary health organisations in New Zealand are responsible for primary health services in 81 local regions.10 Box 1 identifies the features common to these regional frameworks. The factor underlying their success is effective integration of top-down and bottom-up governance, which allows responsive, well integrated and regionally appropriate services to be delivered.

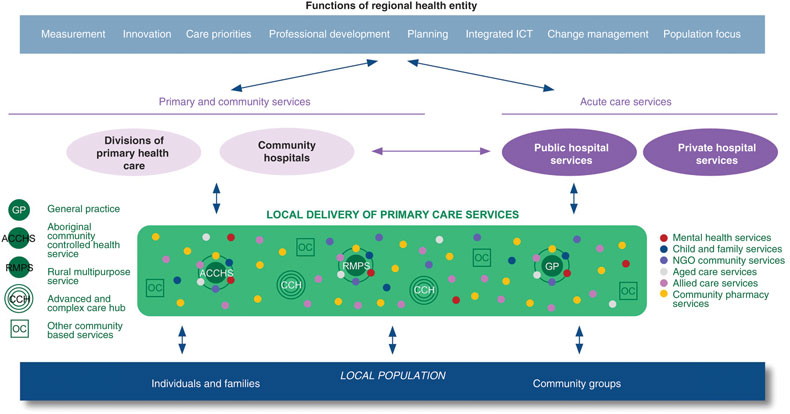

Using existing structures, RHEs could be created to be accountable for the delivery and integration of all heath care within defined geographic areas (Box 2). They would focus mainly on the organisation and delivery of primary and community health care and its smooth interface with the secondary care sector. Rather than creating another level of health bureaucracy, RHE personnel would come from existing providers of cross-sector health care — from district and area health services, Divisions of General Practice, other primary health care organisations, local public and private hospitals, public and private community organisations, and the Indigenous community — working within a sound corporate governance framework. Community representatives would include local business leaders, local government councillors and appropriate independent representatives. This is the model adopted by Ontario’s local health integration networks (Box 1), which operate as not-for-profit organisations (Crown corporations) governed by boards of directors appointed by provincial governments after rigorous merit-based selection processes. The board is responsible for managing its network and is the key point of interaction with government ministries. As with these networks, RHEs would not add another layer of bureaucracy, but provide a governance framework to plan, integrate and fund services from existing providers. They would have both the power and accountability for the delivery of appropriate local care.

The RHE’s initial key roles and responsibilities could include:

integrated service planning across the region;

promotion of integrated clinical care models in agreed local priority areas;

service innovation to deliver patient- and family-centred care;

review of reports from the hospital and primary care sectors about gaps in service and proposed changes, and strong support for appropriate and flexible local health service delivery;

promotion of local information communication technology and e-connectivity;

establishment of an appropriate health workforce for the region;

engagement with local communities to improve service provision and to allocate funds appropriately;

support for updates in practice and professional development needed to implement changing health agendas; and

collation of local health data across the care continuum.

The move to RHEs would need to be progressively and carefully planned. Key milestones would include initial establishment; development of good working relationships across the health and community sectors; coordination of RHE activities with hospital-based activity and Medicare funding at regional level; and service commissioning. The 2009 National Healthcare Agreement (NHA)11 is a cooperative intergovernmental effort to improve all levels of care — preventive programs, primary and community care, hospital and aged care. Proposed RHE arrangements would support the intent of the agreement as well as that of the HAA. However, new arrangements would see the Commonwealth funding RHEs instead of traditional providers of primary care, such as Divisions of General Practice and other community organisations. RHEs would be responsible for funding allocation and local service delivery. RHEs would then work locally with primary health care organisations, hospitals and other community and non-governmental stakeholders to determine who is best placed to provide particular services. Similarly, state and territory governments could allocate the funds they now spend on primary and community care through the RHEs, where they would have a seat alongside other stakeholders. RHEs could also be cosignatories to and recipients of National Partnership Payments, available under the NHA, for initiatives in activity-based funding, health workforce development, subacute care, management of primary-care patients attending emergency departments, preventive health, Indigenous primary health care, oral health, diagnostics and health screening. Similar outcomes could also be achieved if the Commonwealth retained an agreed share of goods and services taxes (currently returned to the states to meet health service costs) to fund the RHE for the provision of appropriate regional health care services.

Under RHE governance, the main focus for achieving patient-centred care would remain each individual’s “health care home” — his or her general practice, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service or rural Multi-Purpose Health Centre. The concept of the health care or medical home, first described by four societies in the United States as a means to improve health in that country,12 combines the traditional values of family medicine — comprehensive, coordinated and integrated patient-centred care — with the e-connectivity and expanded practice teamwork of today. Much has been made of this concept recently, with the NHHRC reporting that more than 60% of Australians enjoy this comprehensive arrangement via their current general practice team.3 Smooth articulation between the patient’s medical home and other community services — mental health, child and maternal health, allied health, palliative care — would be achieved (preferably electronically) by effective referral, transitioned care and interprofessional exchange.

A number of “advanced and complex care hubs” in each region, similar to the Royal College of General Practitioners’ federated model,13 the networked polyclinic in England,14 or “beacon” practice,15 could complement care delivery within RHEs, and provide an accessible, intermediate interface between primary and secondary care services. Their business model could include involvement of a mix of public, private, not-for-profit and non-governmental organisations. Their roles should be determined by the needs of the local population and could include advanced or complex clinical care (management of refractory diabetes, renal failure, exercise electrocardiogram, Holter monitoring), procedures (day surgery, endoscopy), care coordination of patients with complex needs (generally older people), and complex multidisciplinary centre-based care (for patients with dementia or chronic debilitating mental disease). After-hours care, including x-ray, pharmacy, allied health, equipment hire and associated support services (eg, observation beds) would also be within the scope of the hub. General practitioners with special interests and specialist health professionals in these hubs would work with the patients’ usual providers in supporting patients and families to stay at home or within their community. All services would be linked with the individual’s usual care providers via appropriate referral, transitioned care and discharge planning.

All providers within the hub should be focused on teamwork, a culture of service excellence, local capacity building in service delivery, and workforce maximisation. Advanced multidisciplinary and interprofessional teaching and training should be a priority within these hubs, as should smooth linkage and interface arrangements with universities, colleges, and regional training bodies. These hubs are the natural evolution of the GP Super Clinic initiative16 and are consistent with the NHHRC’s Comprehensive Primary Health Care Centres and Services.6

1 Essential features common to internationally established regional governance systems

- Claire L Jackson1

- Caroline Nicholson2

- Eugene P McAteer3

- 1 Discipline of General Practice, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD.

- 2 Mater/University of Queensland Centre for Primary Healthcare Innovation, Mater Hospital, Brisbane, QLD.

- 3 South East Alliance of General Practice, Brisbane, QLD.

None identified.

- 1. Australian Health Ministers’ Conference. National health workforce strategic framework. Sydney: AHMC, 2004. http://www.nhwt.gov.au/documents/National%20Health%20Workforce%20Strategic%20Framework/AHMC%20National%20Workforce%20Strategic%20Framework%202004.pdf (accessed Jan 2010).

- 2. Schoen C, Osborn R, Huynh PT, et al. Primary care and health system performance: adults’ experience in five countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004; Jul-Dec; Suppl Web Exclusives: W4-487-503. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=%22Health+affairs+%28Project+Hope%29%22%5BJour%5D +AND+2004%5Bpdat%5D+AND+Schoen%5Bfirst+author%5D+AND+primary&TransSchema=title (accessed Jan 2010).

- 3. Hurley E, McRae I, Bigg I, et al. The Australian health care system: the potential for efficiency gains. A review of the literature. Canberra: National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission, 2009. http://www.nhhrc.org.au/internet/nhhrc/publishing.nsf/Content/A5665B8B9EAB34B2CA2575CB00184FB9/$File/Potential%20Efficiency%20Gains%20-%20NHHRC%20Background%20 Paper.pdf (accessed Jan 2010).

- 4. Doggett J. A new approach to primary health care for Australia. Sydney: Centre for Policy Development, 2007. (CPD Occasional Paper No. 1.) http://cpd.org.au/sites/cpd/files/u51504/a_new_approach_to_Primary_Care_-_CPD_June_07.pdf (accessed Jan 2010).

- 5. Consumers Health Forum of Australia. Submission on the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission’s interim report — a healthier future for all Australians. March 2009. http://www.chf.org.au/pdfs/sub/sub-517-nhhrc-interim-report.pdf (accessed Jan 2010).

- 6. National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. A healthier future for all Australians: final report June 2009. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2009. http://www.nhhrc.org.au/internet/nhhrc/publishing.nsf/Content/nhhrc-report (accessed Jan 2009)

- 7. National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. A healthier future for all Australians — interim report December 2008. Canberra: NHHRC, 2009. http://www.nhhrc.org.au/internet/nhhrc/publishing.nsf/Content/BA7D3EF4EC7A1 F2BCA25 755B001817EC/$File/NHHRC.pdf (accessed Jan 2010).

- 8. National Health Service of the United Kingdom. Authorities and trusts. http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/aboutnhs/Pages/Authoritiesandtrusts.aspx (accessed Jan 2010).

- 9. Ontario’s Local Health Integration Networks. Ontario’s LHIN Legislation. http:// www.lhins.on.ca/legislation.aspx?ekmensel=e2f22c9a_72_328_btnlink (accessed Jan 2010).

- 10. PHONZ Primary Health Organizations New Zealand Inc. http://www.phonz. net.nz/phonznew/ (accessed Jan 2010).

- 11. Council of Australian Governments. National Healthcare Agreement. http://www.coag.gov.au/intergov_agreements/federal_financial_relations/docs/IGA_FFR_ScheduleF_National_Healthcare_Agreement.pdf (accessed Jan 2010).

- 12. Robert Graham Center. The patient centred medical home. November 2007. http://www.graham-center.org/online/etc/medialib/graham/documents/publications/mongraphs-books/2007/rgcmo-medical-home.Par.0001.File.tmp/rgcmo-medical-home.pdf (accessed Jan 2010, link updated 22 Feb 10).

- 13. Lakhani M, Baker M, Field S. The future direction of general practice: a roadmap. London: Royal College of General Practitioners, 2007. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/pdf/Roadmap_embargoed%2011am%2013%20Sept.pdf (accessed Jan 2010).

- 14. Imison C, Naylor C, Maybin J. Under one roof: will polyclinics deliver integrated care? London: The King’s Fund, 2008. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/applications/research/index.rm?id=38&skip=20&filter=publications&sort=date (accessed Jan 2010).

- 15. Jackson CL, Askew DA, Nicholson C, Brooks PM. The primary care amplification model: taking the best of primary care forward. BMC Health Serv Res 2008; 8: 268.

- 16. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. GP super clinics. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/pacd-gpsuperclinics (accessed Jan 2010).

Abstract

Australia’s health care system is at a crossroads. It is recognised that the fragmentation of health services, largely caused by the split between Commonwealth and state government funding responsibilities, is undermining patient care.

The National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission (NHHRC) has advanced two models of health-system governance to redress this situation — neither incorporating the regional approach so prominent in submissions to the NHHRC and included in Option B of the NHHRC interim report.

A regional governance framework such as that described in this paper could keep faith with the importance widely given to local engagement during the consultation process; sit neatly within the NHHRC’s Healthy Australia Accord option; make regions responsible for funding allocation and service delivery; eliminate major weaknesses in our current system; and provide stability to the system at a time of significant reform.