Clinical records

|

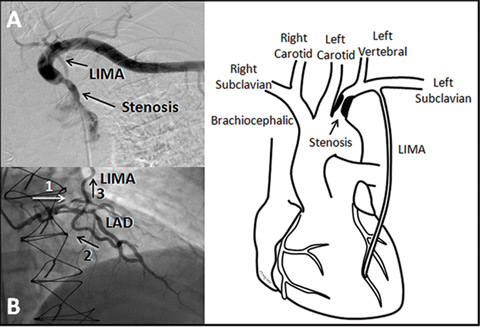

| 1 A: Subtracted angiogram showing the subclavian stenosis prior to the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) origin. B: Selective left coronary angiogram showing flow down the left anterior descending artery (LAD) (1) then retrograde up the LIMA (2 and 3). C: Diagram showing the relationship of the stenosis to the left vertebral and LIMA origins. |

|

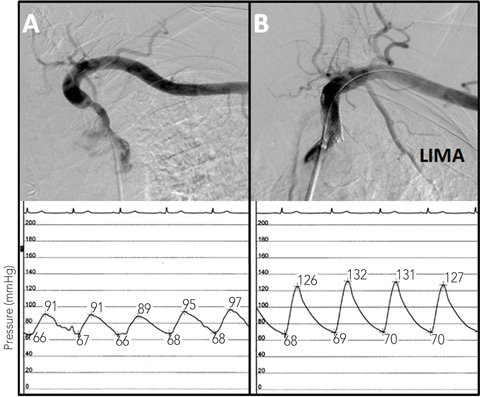

| 2: Angiograms of the left subclavian stenosis before (A) and after (B) stenting, showing the improvement in antegrade LIMA flow. The intra-arterial subclavian pressure tracings are shown below the angiograms. Before stenting (left) the pressure tracing is blunted, while after stenting (right), there is an improvement in blood pressure and normalisation of the arterial waveform. |

A potentially clinically significant stenosis in the subclavian or brachiocephalic arteries will produce a difference in systolic blood pressure between the right and left brachial arteries of 15–20 mmHg or more.1 Therefore, bilateral arm blood pressure measurements should be taken in symptomatic patients after coronary artery bypass using internal mammary artery grafts.

Unfortunately, this simple non-invasive assessment is often overlooked, as it was in the patients reported here. A haphazard approach to catheterisation of the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) graft can also cause the diagnosis to be missed, as the catheter can often cross a significant subclavian stenosis. Meticulous comparison of the subclavian and aortic pressure tracings will identify the gradient and enable diagnosis. The difference in pressure between the arms may be reduced or absent in patients with significant bilateral subclavian and/or brachiocephalic disease, a scenario more likely in patients with extensive atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease elsewhere.2

Coronary subclavian steal syndrome describes angina related to a subclavian stenosis with retrograde flow up the LIMA graft. This reverse LIMA flow results from lower vascular resistance and blood pressure in the arm compared with the myocardial territory supplied by the LIMA. However, steal with reverse LIMA flow is not an absolute requirement for angina. In our patients, none had angina precipitated by left arm activity that would uncover a latent steal syndrome. In many cases, subclavian stenosis behaves physiologically more like a very proximal LIMA stenosis. In this case, “LIMA-inflow syndrome” may be a more accurate term. Regardless of the semantics, this is a rare phenomenon that is reported in 0.1%–5.0% of patients after coronary artery bypass grafting.2-4 The differential diagnosis includes other diseases obstructing large arteries such as Takayasu’s arteritis (especially in young women), post-radiation arteritis, and giant cell arteritis (especially in older patients).

The management of subclavian and brachiocephalic stenoses depends on the clinical presentation. All patients require medical therapy with intensive atherosclerosis risk factor reduction, as the 10-year total and cardiovascular mortality approaches 40%–50%.1 Asymptomatic individuals do not need intervention, so non-invasive imaging is unnecessary. In symptomatic patients, non-invasive imaging with contrast computed tomography or magnetic resonance or conventional angiography can confirm the diagnosis when an intervention is anticipated. Traditionally, symptomatic patients were treated with carotid-subclavian bypass. However, percutaneous angioplasty and stenting are increasingly used because of their lower morbidity and similar long-term results.2,5-8 The risk of stroke from stenting is low, and no higher than for surgical bypass.2,5-8 Post-procedural management includes treatment with aspirin for life and clopidogrel for at least 1 month. Clinical follow-up includes surveillance for recurrent symptoms with a difference in brachial blood pressures.

Lessons from practice

Systolic blood pressure should be measured in both arms with a standard sphygmomanometer in all patients with past coronary artery bypass grafting and progressive angina or acute coronary syndromes.

A difference in systolic blood pressure of greater than 15–20 mmHg between the right and left arms is strongly suggestive of subclavian stenosis.

Asymptomatic subclavian stenosis does not require imaging or revascularisation, but does denote high cardiovascular risk warranting intensive risk factor reduction.

Symptomatic subclavian stenosis can be successfully treated with percutaneous stenting.

- 1. Aboyans V, Criqui MH, McDermott MM, et al. The vital prognosis of subclavian stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49: 1540-1545.

- 2. Takach TJ, Reul GJ, Cooley DA, et al. Myocardial thievery: the coronary-subclavian steal syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg 2006; 81: 386-392.

- 3. Lobato EB, Kern KB, Bauder-Heit J, et al. Incidence of coronary-subclavian steal syndrome in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2001; 15: 689-692.

- 4. Osborn LA, Vernon SM, Reynolds B, et al. Screening for subclavian artery stenosis in patients who are candidates for coronary bypass surgery. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2002; 56: 162-165.

- 5. Al-Mubarak N, Liu MW, Dean LS, et al. Immediate and late outcomes of subclavian artery stenting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 1999; 46: 169-172.

- 6. De Vries JP, Jager LC, Van den Berg JC, et al. Durability of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for obstructive lesions of proximal subclavian artery: long-term results. J Vasc Surg 2005; 41: 19-23.

- 7. Marques KM, Ernst SM, Mast EG, et al. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty of the left subclavian artery to prevent or treat the coronary-subclavian steal syndrome. Am J Cardiol 1996; 78: 687-690.

- 8. Patel SN, White CJ, Collins TJ, et al. Catheter-based treatment of the subclavian and innominate arteries. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2008; 71: 963-968.

None identified.