An immunocompetent patient developed a necrotising soft tissue infection after being pecked by a magpie. The infection was caused by the fungus Saksenaea vasiformis, an uncommon human pathogen. Special culture techniques are required to induce sporulation to enable identification of the organism.

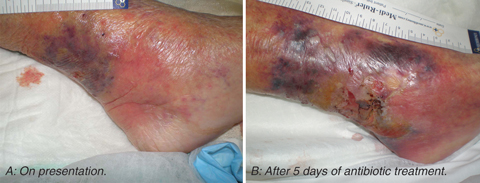

An 84-year-old woman presented to our hospital emergency department with cellulitis of the left lower leg. There was a small, dry eschar and some adjacent purplish discolouration (Box 1, A). Eleven days previously, she had been pecked above the left ankle by a magpie (Gymnorhina tibicen), which her daughter kept as a pet.

The patient’s leg failed to improve during the first week of treatment (Box 1, B), despite the addition of metronidazole on Day 5 after admission and gentamicin on Day 6. The antibiotics were changed to ticarcillin–clavulanic acid on Day 9. The patient had low-grade fevers from Day 7 and her white cell count progressively rose to 31.1 × 109/L.

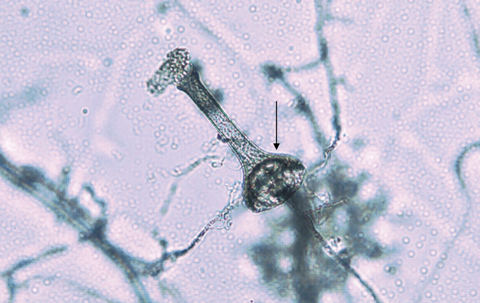

Histopathological examination of the debrided tissue showed coagulative necrosis with scattered fungal hyphae, especially within blood vessels. The hyphae had occasional septa and branched at variable angles. The more viable areas contained acute inflammatory cells. A white downy fungus grew in culture from a tissue specimen after 5 days, but the fungus was difficult to identify as it failed to sporulate in culture. When subsequently grown on Czapek Dox agar, the isolate eventually produced vase-shaped sporangia typical of Saksenaea vasiformis (Box 2).

S. vasiformis was first described in 1953 by Saksena as a new zygomycete isolated from forest soil in India.1 Infection due to S. vasiformis was first observed in 1977 in a young man who had sustained severe cranial trauma in a motor vehicle accident. The infection involved the eye and brain.2 A total of 29 cases of human infection due to S. vasiformis have since been reported in the English language literature.3,4 Most cases occurred as cutaneous zygomycosis in immunocompetent patients after traumatic inoculation. S. vasiformis typically requires special culture techniques to induce sporulation and enable definitive identification. It shares these characteristics with Apophysomyces elegans, another zygomycete.5

Reports in the literature of skin or soft tissue infections following bird pecking injuries are sparse. These include a Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of the finger after a swan bite6 and a Bacteroides scalp infection after an owl attack.7 More serious infections relating to trauma involving a bird have included septic arthritis of the knee after a chicken bite8 and a fatal brain abscess in a child caused by a rooster peck.9 Zygomycoses have been transmitted by insect or spider bites, with the pathogens reported as Rhizopus spp,10,11 Apophysomyces elegans12 and Mucor hiemalis.13

- 1. Saksena SB. A new genus of the Mucorales. Mycologia 1953; 45: 426-436.

- 2. Dean DF, Ajello L, Irwin RS, et al. Cranial zygomycosis caused by Saksenaea vasiformis. J Neurosurg 1977; 46: 97-103.

- 3. Vega W, Orellana M, Zaror L, et al. Saksenaea vasiformis infections: case report and literature review. Mycopathologia 2006; 162: 289-294.

- 4. Blanchet D, Dannaoui E, Fior A, et al. Saksenaea vasiformis infection, French Guiana. Emerg Infect Dis 2008; 14: 342-344.

- 5. Chakrabarti A, Kumar P, Padhye AA, et al. Primary cutaneous zygomycosis due to Saksenaea vasiformis and Apophysomyces elegans. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 24: 580-583.

- 6. Ebrey RJ, Hayek LJHE. Antibiotic prophylaxis after swan bite. Lancet 1997; 350: 340.

- 7. Davis B, Wenzel RP. Striges scalp: Bacteroides infection after an owl attack. J Infect Dis 1992; 165: 975-976.

- 8. Huang C-M, Chou C-T, Chen H-T, Jim Y-F. Septic arthritis following a chicken bite. Clin Rheumatol 1998; 17: 540-542.

- 9. Berkowitz FE, Jacobs DW. Fatal case of brain abscess caused by rooster pecking. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1987; 6: 941-942.

- 10. Adam RD, Hunter G, Di Tomasso J, Comerci G Jr. Mucormycosis: emerging prominence of cutaneous infections. Clin Infect Dis 1994; 19: 67-76.

- 11. Hicks WL Jr, Nowels K, Troxel J. Primary cutaneous mucormycosis. Am J Otolaryngol 1995; 16: 265-268.

- 12. Weinberg WG, Wade BH, Cieny G III, et al. Invasive infection due to Apophysomyces elegans in immunocompetent hosts. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 17: 881-884.

- 13. Prevoo RL, Starink TM, de Haan P. Primary cutaneous mucormycosis in a healthy young girl. Report of a case caused by Mucor hiemalis Wehmer. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991; 24: 882-885.

I would like to thank Dr Stephen Cox, General Surgeon at Calvary Mater Newcastle, for allowing me to see the patient and publish this report; Sr Theresa Richards, Clinical Nurse Specialist in wound care at Calvary Mater Newcastle, for the photographs of the patient; and Mr David Pacey, Medical Laboratory Scientist, for identifying the fungus and providing photographs of its morphology.

None identified.