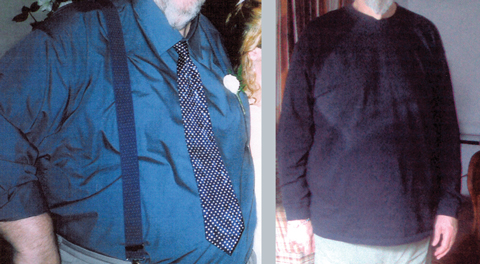

We report the case of a 59-year-old severely obese man with coexisting type 2 diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia who was treated with a very-low-calorie diet (VLCD) program for 12 months. He continued to lose weight during the treatment, with marked improvement in his comorbidities and no adverse effects. This case demonstrates that prolonged use of a VLCD under close medical supervision is safe and effective in certain obese patients.

Initial laboratory investigations revealed a random blood glucose level of 22.2 mmol/L (reference range, 3.3–5.5 mmol/L) and a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level of 12.2% (reference range, 4.3%–6.0%). Urinary ketones were not detected. Levels of electrolytes, inflammatory markers and vitamin B12 were normal. Liver function tests showed a mild generalised elevation, and lipid levels were raised (Box 1). An electrocardiogram (ECG), non-contrast computed tomography brain scan, lumbar puncture and carotid Doppler ultrasound were normal. Nerve conduction studies showed an axonal sensorimotor neuropathy, with the lower limbs more severely affected than the upper limbs.

Over the 12 months, the patient’s weight fell steadily (Box 2, Box 3). At 1-year follow-up, he had lost 43% of his initial weight and was down to 96.5 kg (BMI, 26.7 kg/m2). He was normotensive (125/80 mmHg), and his fasting blood glucose and HbA1c levels were in the non-diabetic range. Full blood examination, electrocardiographic readings, and levels of electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, folate, vitamin B12, vitamin D and uric acid were normal. Liver function tests had normalised, and the lipid profile had improved significantly (Box 1). Bone mineral density (measured by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry) was normal at 6 and 12 months after commencement of the VLCD. Neurological symptoms improved, with persistence of limb weakness and sensory loss.

VLCDs involve replacement of meals with foods or formulas providing 1675–3350 kJ/day. They are commonly used in medically supervised weight reduction programs for patients with BMI > 30 kg/m2 (or > 27 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities), or for whom rapid weight loss is necessary. Several formulations are available without prescription (Box 4). VLCDs should provide at least 0.8 g protein per kilogram of ideal bodyweight per day (to preserve lean body mass1), along with the recommended daily allowances of minerals, vitamins, trace elements and essential fatty acids. Around 10 g/day fat is recommended to stimulate gallbladder contraction.2 Although optimal caloric and carbohydrate intakes are unknown, 50 g carbohydrate daily has been suggested as a suitable quantity to maintain normoglycaemia and to prevent loss of electrolytes and protein.2 There is no advantage in reducing energy intake below 3350 kJ/day.3

Treatment duration varies but is usually 8–16 weeks.1 To our knowledge, our report is the first to document the use of a VLCD for 12 months.

There is concern about the safety of VLCDs, most of which stems from the occurrence of over 60 deaths associated with a popular liquid protein diet, available in the 1970s, that consisted entirely of solutions of collagen or gelatine hydrolysates.4 Many of the deaths occurred in people with pre-existing comorbidities.4 However, 17 deaths (16 in women) occurred in relatively young (median age, 35 years) and otherwise reasonably healthy people. These 17 people, who were severely obese (mean BMI, 40.6 kg/m2), remained on the diet for an average of 5 months and lost a large amount of weight (mean, 35%). Postmortem findings were consistent with the cardiac effects of protein-calorie malnutrition (which include myocardial atrophy, QT prolongation and ventricular arrhythmias).5

In contrast, VLCDs in current use contain high-quality protein and appear to be safe.1 In 1998, Rössner described the case of a patient who had lived solely on a VLCD preparation for 46 weeks without medical supervision, in whom no adverse events occurred other than cholelithiasis and one episode of palpitations, after which ECG monitoring over a 24-hour period showed no abnormality.6

When beginning a VLCD, liver function tests, lipid profile measurements, a full blood count and iron studies should be carried out, and levels of electrolytes, creatinine and uric acid should be measured. Testing of electrolyte and creatinine levels should be repeated about 6 weeks after commencement, or earlier if more careful monitoring is required (eg, in patients who have renal impairment or are using diuretics). If the VLCD is to continue for more than 12 weeks, it is advisable to repeat the baseline tests at least every 2 months.7

Obese people typically achieve a mean weight loss of 1.5–2.5 kg per week using a VLCD. A 2001 meta-analysis concluded that, after using a VLCD, subjects maintained a significantly greater weight loss at 4.5 years (mean loss, 6.6% of initial weight) than after a hypocaloric balanced diet (mean loss, 2.1% of initial weight).8 Taking meal replacements once or twice daily in conjunction with a reduced-calorie diet is also effective for long-term weight maintenance.9

Advantages of VLCDs include the motivating effect of rapid weight loss, the convenience of meal replacement (which improves adherence compared with an ad-libitum low-fat diet)10 and a mild ketosis, which may suppress hunger.7 VLCDs also help with several obesity-related comorbidities by reducing levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, triglycerides and blood glucose and by reducing blood pressure, insulin resistance1 and hepatic steatosis.11 All of these benefits were obtained by our patient.

To date, bariatric surgery has been the most effective long-term treatment option for obesity. The Swedish Obese Subjects Study, a large prospective controlled study of severely obese patients, found significantly greater weight loss in the surgically treated group than the control group (23.4% bodyweight lost [surgical group] v 0.1% gained [control group] at 2 years, and 16.1% lost [surgical group] v 1.6% gained [control group] at 10 years).12 Similar weight reductions after surgery were reported in a study of mildly to moderately obese subjects13 and in a meta-analysis of bariatric surgery trials.14

Pharmacotherapy for weight loss has only modest benefits, with loss of around 3%–5% bodyweight over 1–4 years reported in a recent meta-analysis.15

- 1. Mustajoki P, Pekkarinen T. Very low energy diets in the treatment of obesity. Obes Rev 2001; 2: 61-72.

- 2. Saris WH. Very-low-calorie diets and sustained weight loss. Obes Res 2001; 9 Suppl 4: 295S-301S.

- 3. Foster GD, Wadden TA, Peterson FJ, et al. A controlled comparison of three very-low-calorie diets: effects on weight, body composition, and symptoms. Am J Clin Nutr 1992; 55: 811-817.

- 4. Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, Brownell KD. Very low calorie diets: their efficacy, safety, and future. Ann Intern Med 1983; 99: 675-684.

- 5. Isner JM, Sours HE, Paris AL, et al. Sudden, unexpected death in avid dieters using the liquid-protein-modified-fast diet. Observations in 17 patients and the role of the prolonged QT interval. Circulation 1979; 60: 1401-1412.

- 6. Rössner S. Effects of 46 weeks of very-low-calorie-diet treatment on weight loss and cardiac function — a case report. Obes Res 1998; 6: 462-463.

- 7. Delbridge E, Proietto J. State of the science: VLED (very low energy diet) for obesity. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2006; 15 Suppl: 49-54.

- 8. Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, et al. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2001; 74: 579-584.

- 9. Rothacker DQ. Five-year self-management of weight using meal replacements: comparison with matched controls in rural Wisconsin. Nutrition 2000; 16: 344-348.

- 10. Noakes M, Foster PR, Keogh JB, et al. Meal replacements are as effective as structured weight-loss diets for treating obesity in adults with features of metabolic syndrome. J Nutr 2004; 134: 1894-1899.

- 11. Lewis MC, Phillips ML, Slavotinek JP, et al. Change in liver size and fat content after treatment with Optifast very low calorie diet. Obes Surg 2006; 16: 697-701.

- 12. Sjöström L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 2683-2693.

- 13. O’Brien PE, Dixon JB, Laurie C, et al. Treatment of mild to moderate obesity with laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding or an intensive medical program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144: 625-633.

- 14. Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004; 292: 1724-1737.

- 15. Rucker D, Padwal R, Li SK, et al. Long-term pharmacotherapy for obesity and overweight: updated meta-analysis. BMJ 2007; 335: 1194-1199.

Priya Sumithran is supported by an Endocrine Society of Australia scholarship and a Royal Australasian College of Physicians Shields Research Entry Scholarship. These funding sources had no role in the writing of our article.

Joseph Proietto is Chairman of the Medical Advisory Committee for Optifast (Novartis).