In Australia, the peak of the “Spanish flu” pandemic occurred in mid June 1919. In that week, 1315 people were being treated for influenza in hospitals in New South Wales. Of those, fewer than 900 survived. By November that year, the pandemic for Australia was essentially over, but nationwide it had taken more than 10 000 lives.1

In 2003, the virus re-emerged in Thailand and Vietnam, spreading rapidly through poultry flocks. Human cases occurred, but in all but one case there was clear contact with poultry. Intensive efforts at culling poultry in affected areas seemed to halt the spread. However, in May 2005, the virus was discovered in many bird species in the Qinghai province of western China. From there, it has spread across Europe and down into the Middle East and Africa. More than 150 million birds have been destroyed and more than 200 people infected. The mortality rate of what is termed “avian influenza” or “bird flu” in humans is greater than 50%.2,3

Indonesia is currently the country most affected by bird flu. Outbreaks in poultry have occurred in most provinces. Sporadic human cases continue to occur. A cluster of seven cases in one family in a village in Sumatra gave rise to worldwide concern. It was considered likely that human-to-human transmission had occurred.2

The Australian health response plan is detailed in the Australian health management plan for pandemic influenza (AHMPPI). This document is aimed at the general public. It is accompanied by several technical annexes: the Interim infection control guidelines for pandemic influenza in healthcare and community settings and the Interim national pandemic influenza clinical guidelines have been published; the Guidelines for management of pandemic influenza in primary care settings are close to finalisation.

The AHMPPI, the annexes, the communications strategy and additional information are available on the Department of Health and Ageing website <http://www.health.gov.au>.

The actions at each phase of the pandemic (Box 1) are outlined in the AHMPPI. The current global designation of phase by the World Health Organization is alert level 3 (Overseas 3). Australia is technically in Phase 0.

The antiviral stockpile, almost entirely the neuraminidase inhibitors oral oseltamivir and inhalant zanamivir, will contain 8.75 million courses by early 2007. Seasonal studies have shown that these antivirals reduce the duration and severity of disease if given early, and are effective at preventing infection.4,5

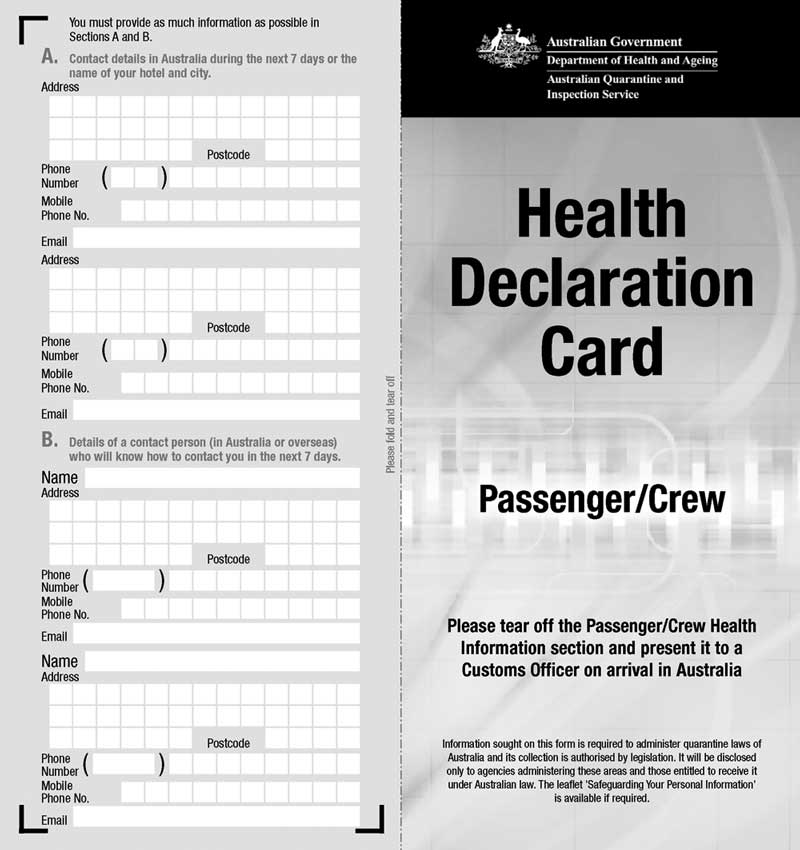

Other measures include using thermal scanners to screen for fever, clinical assessment of symptomatic passengers by nurses stationed at the border, and short-term quarantine of arriving passengers potentially exposed to the virus. All passengers will be required to fill out “health declaration cards”, which will detail symptoms and request personal and contact details (Box 2). This will facilitate timely contact tracing.

A person with influenza infects one to two other people. This is far less than the infectivity of, for example, polio or measles, in which one person may infect on average five and 10 others, respectively.6 The spread of influenza is largely due to its very short incubation period. This means if an infected person can be identified early and quarantined then the chance of that person causing an epidemic is greatly reduced.

The Australian Government has commissioned experts in Australia to model the effect of public health interventions on the spread of a pandemic. The results indicate that the use of quarantine, social distancing, and personal hygiene could have a significant effect in slowing and reducing the impact of a pandemic.7 The addition of antivirals greatly assists in the “ring fencing” of an outbreak. The results of this modelling have been echoed by international studies.8-11

Social distancing refers to all non-pharmaceutical methods of infection control. It includes reducing contacts in the community by not holding mass gatherings and by encouraging individuals to keep distance from others in communal settings. It also includes personal hygiene such as frequent hand washing, cough and sneeze etiquette, and reduction in close human contact (no kissing, no hugging). Social distancing is an extremely effective tool, particularly when applied both in the community and in the home.7,8

The combined effect of quarantine, social distancing, and targeted use of antivirals may allow a pandemic to be controlled or prevented from taking off in Australia for more than a year.7-11

The authority and decision-making arrangements are set out in the National action plan for human influenza pandemic, which can be found at <http://www.pmc.gov.au>.

1 Pandemic phases

- John S Horvath1

- Moira McKinnon2

- Leslee Roberts3

- Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra, ACT.

None identified.

- 1. Paton RT. Report of the Director-General of Public Health to the Honorable The Minister of Public Health. Section V. Report on the influenza epidemic in New South Wales in 1919. Sydney: NSW Health Department, 1920.

- 2. World Health Organization. Epidemic and pandemic alert and response: avian influenza. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/en/index.html (accessed Jul 2006).

- 3. Webster RG, Peiris M, Chen H, Guan Y. H5N1 outbreaks and enzootic influenza. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12: 3-8.

- 4. Cooper NJ, Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, et al. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in treatment and prevention of influenza A and B: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2003; 326: 1235-1240.

- 5. Jefferson T, Demicheli V, Deeks J, Rivetti D. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults (Cochrane review). The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2005. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smallpox: disease, prevention, and intervention. Module 1. History and epidemiology of global smallpox eradication [course notes]. http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/smallpox/training/overview/ (accessed Oct 2006).

- 7. Becker NG, Glass K, Barnes B, et al. Using mathematical models to assess responses to an outbreak of an emerged viral respiratory disease. Final report to the Department of Health and Ageing. Canberra: National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University, 2006.

- 8. Wu JT, Riley S, Fraser C, Leung G. Reducing the impact of the next influenza pandemic using household-based public health interventions. PLoS Med 2006; 3: e361.

- 9. Glass RJ, Glass LM, Beyeler WE. Local mitigation strategies for pandemic influenza: prepared for the Department of Homeland Security under the National Infrastructure Simulation and Analysis Center. Report no. SAND2005–7955J. Washington, DC: Department of Homeland Security, 2005.

- 10. Longini IM Jr, Nizam A, Xu S, et al. Containing pandemic influenza at the source. Science 2005; 309: 1083-1087.

- 11. Ferguson NM, Cummings DAT, Cauchemez S, et al. Strategies for containing an emerging influenza pandemic in Southeast Asia. Nature 2005; 437: 209-214.

Abstract

Australia’s preparedness for a potential influenza pandemic involves many players, from individual health carers to interdepartmental government committees. It embraces a wide number of strategies from the management of the disease to facilitating business continuity.

The key strategy underlying Australia’s planned response is an intensive effort to reduce transmission of the virus. This includes actions to reduce the likelihood of entry of the virus into the country and to contain outbreaks when they occur. Containment will provide time to allow production of a matched vaccine.

The health strategies are outlined in the Australian health management plan for pandemic influenza. The plan is accompanied by technical annexes setting out key considerations and guidelines in the areas of clinical management and infection control.

National plans present overall strategies and guidance, but the operational details can only be determined by individual states and territories, regions, and the services themselves.

Primary health care practices will be on the frontline of an influenza pandemic. Every practice needs a plan that defines the roles of staff, incorporates infection control and staff protection measures, and considers business continuity. Most importantly, a practice needs to know how to implement that plan.