Abdominal distension is a common problem in clinical practice, but, because of its trivial signs and symptoms, many patients ignore it as a potential cause for concern.1 Common pathological causes of abdominal distension include hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, intra-abdominal masses or inflammation, intestinal obstruction, colorectal tumours and ascites.

Colorectal cancer, one of the common gastrointestinal diseases encountered in clinical practice,2-4 tends to be symptomless early in its course. Many methods have been used to diagnose colorectal cancer, including faecal blood testing,5 flexible sigmoidoscopy,6 double-contrast barium enema,7 endoscopic or virtual colonoscopy,8 and DNA markers.9 Although abdominal ultrasonography is widely used to diagnose patients with acute abdomen,10-11 its role in diagnosing colorectal cancers has not been tested. The aim of our study was to determine the accuracy of abdominal ultrasonography for diagnosis of colorectal cancers in patients presenting with abdominal distension.

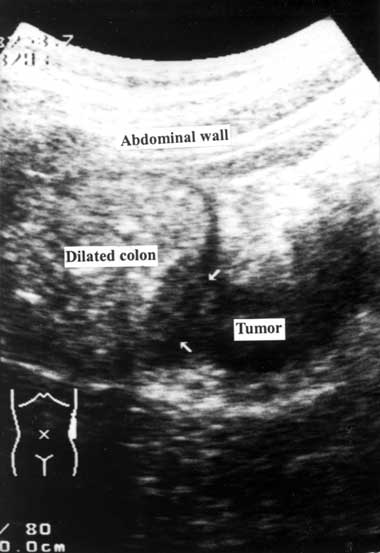

A detailed medical history was obtained and a physical examination was performed by a member of the emergency or surgical house staff. After giving informed consent, the patient underwent an ultrasonographic examination, performed by staff emergency physicians or staff surgeons who had completed the fundamental gastrointestinal ultrasonographic training course provided by the Society of Ultrasound in Medicine, Taiwan. Ultrasonography was performed with a handheld 3.75–6 MHz curved array transducer (Toshiba SSA-340A, SSA-550A; Tochigi-Ken, Japan) over the patient’s abdomen, screening along the caecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon, splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum. Any additional or abnormal ultrasonographic changes were described and the ultrasonographic diagnosis was recorded. To reduce interference from gas in the bowel (which blurs the ultrasound image), the patient’s position was changed from supine to the right or left lateral decubitus position during the ultrasonographic examination. Because normal bowel loop is compressible, an incompressible lesion within the colon or extending outside the colonic wall was suggestive of a colorectal tumour. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of a colorectal tumour was based on a proximal colon dilatation with a distal colon collapse and a mass lesion inside the transitional colon (Box 1).

From our results we calculated the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value and negative predictive value12 of ultrasonography for diagnosing colorectal cancer.

During the study period, 596 consecutive adult patients with abdominal distension were admitted to the emergency department, of whom 85 were excluded because they met the exclusion criteria (Box 2). The remaining 511 patients agreed to participate in the study. There were 288 men and 223 women, with a mean age of 58.2 years (range, 16–93 years). In this group, common symptoms associated with abdominal distension were abdominal pain (71%), constipation (41%) and vomiting (22%). The results of ultrasonography compared with colonoscopy and CT scanning are shown in Box 3. A total of 97 patients (19.0%) with abdominal distension had colorectal cancer. In 90 of 95 cases of suspected cancer reported on ultrasonography, colonoscopic findings supported the diagnosis; 409 of the 416 negative ultrasonographic reports were supported by CT findings.

Although ultrasonography has been widely used in patients with acute abdomen,10-11 our study is the first, to our knowledge, to use ultrasonography to diagnose colorectal cancers in patients with abdominal distension. It was used only in a special subgroup of patients, and most of the cancers diagnosed were at an advanced stage. We are not suggesting that ultrasonography be used routinely as a substitute for colonoscopy8 or barium enema7 in screening for colorectal cancer.

Although our results showed that ultrasonography had high sensitivity for detecting colorectal cancer, the technique has three important limitations. Firstly, because ultrasound cannot penetrate gas,10 abdominal pathologies can be masked by the presence of gas in the bowel. Thus, repeat ultrasonographic examination is indicated in patients with unclear ultrasonographic findings due to marked bowel gas. Secondly, because ultrasound cannot penetrate bone, colorectal tumours in the middle and lower third of the rectum can be missed. Thirdly, the accuracy of ultrasonographic examination is operator-dependent. An ultrasonographer requires adequate training, skill and experience10 to perform ultrasonography and interpret the results accurately.

1 Longitudinal scan showing proximal colon dilatation with a mass lesion (arrows) inside the descending colon

Received 21 December 2005, accepted 21 March 2006

- Shyr-Chyr Chen1

- Zui-Shen Yen2

- Hsiu-Po Wang3

- Chien-Chang Lee4

- Chiung-Yuan Hsu5

- Wen-Jone Chen6

- Chien-Yao Hsu7

- Hong-Shiee Lai8

- Fang-Yue Lin9

- Wei-Jao Chen10

- National Taiwan University Hospital and National Taiwan University College of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan.

None identified.

- 1. Glickman RM, Isselbacher KJ. Abdominal swelling and ascites. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Isselbacher KJ, et al, editors. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 14th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998: 255-257.

- 2. Schoenfeld P, Cash B, Flood A, et al. Colonoscopic screening of average-risk women for colorectal neoplasia. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 2061-2068.

- 3. Walsh JME, Terdiman JP. Colorectal cancer screening: scientific review. JAMA 2003; 289: 1288-1296.

- 4. Sung JJY, Chan FKL, Leung WK, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer in Chinese: comparison of fecal occult blood test, flexible sigmoid-oscopy, and colonoscopy. Gastroenterology 2003; 124: 608-614.

- 5. Mak T, Lalloo F, Evans DGR, Hill J. Molecular stool screening for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2004; 91: 790-800.

- 6. Imperiale TF, Wagner DR, Lin CY, et al. Risk of advanced proximal neoplasms in asymptomatic adults according to the distal colorectal findings. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 169-174.

- 7. Hixson LJ, Fennerty MB, Sampliner RE, et al. Prospective study of the frequency and size distribution of polyps missed by colonoscopy. J Natl Cancer Inst 1990; 82: 1769-1772.

- 8. Hawes RH. Does virtual colonoscopy have a major role in population-based screening? Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2002; 12: 85-91.

- 9. Dong SM, Traverso G, Johnson C, et al. Detecting colorectal cancer in stool with the use of multiple genetic targets. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001; 93: 858-865.

- 10. Puylaert JB, van der Zant FM, Rijke AM. Sonography and the acute abdomen: practical considerations. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997; 168: 179-186.

- 11. Chen SC, Lee CC, Hsu CY, et al. Progressive increase of bowel wall thickness is a reliable indicator for surgery in patients with adhesive small bowel obstruction. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 1764-1771.

- 12. Zhou X-H, Obuchowski NA, McClish DK. Statistical methods in diagnostic medicine. New York: Wiley, 2002.

Abstract

Objective: To determine the usefulness of abdominal ultrasonography for diagnosing colorectal cancer in patients presenting with abdominal distension.

Design, setting and participants: A prospective case series of consecutive adult patients with abdominal distension admitted to the National Taiwan University Hospital between January 2001 and July 2004. All participants were examined by abdominal ultrasonography. Those with suspected colorectal tumours on ultrasonography had follow-up colonoscopy, while all other patients had computed tomography scans.

Main outcome measures: Accuracy of abdominal ultrasonography for diagnosing colorectal cancer in patients with abdominal distension; incidence of colorectal cancer.

Results: Of 511 patients eligible for inclusion in our study, 97 (19.0%) were confirmed to have colorectal cancer. For diagnosis of colorectal cancer, ultrasonography had a sensitivity of 92.8% (95% CI, 85.2%–96.8%); a specificity of 98.8% (95% CI, 97.0%–99.6%); a positive predictive value of 94.7% (95% CI, 87.6%–98.0%); a negative predictive value of 98.3% (95% CI 96.4%–99.3%); and an accuracy of 97.7%.

Conclusion: Ultrasonography is a sensitive tool for diagnosing colorectal cancer in patients presenting with abdominal distension.