Rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults are mineralisation disorders in which the structural integrity of bone is reduced because of a deficient supply of calcium to the growth plate and bone surface. Rickets is an abnormality of the growth plate and osteomalacia an abnormality of bone. Causes include a very low dietary calcium intake,1 calcium malabsorption due to a bowel disorder such as coeliac disease, and secondary malabsorption due to vitamin D deficiency caused by lack of sunlight exposure2 (Box 2).

Factors that reduce sunlight exposure include infirmity, dress code, skin colour and sunlight sensitivity.3 The disorder is clinically more evident in children because of their greater calcium requirement for skeletal growth. Rickets and osteomalacia can also be caused by phosphate deficiency (see below).

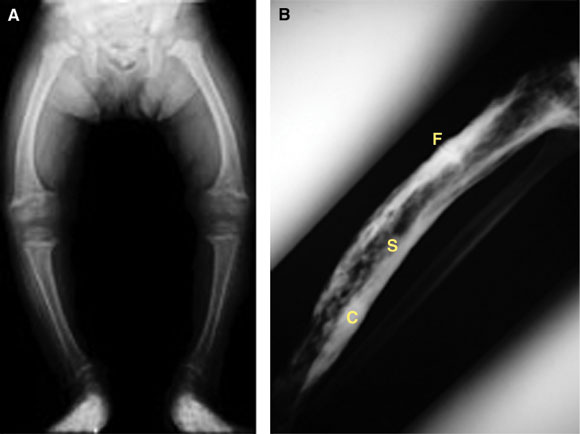

In children, decreased structural integrity of bone causes a variety of anatomical abnormalities, including genu valgum and genu varum (Box 3A), rachitic rosary (palpable bead-like enlargement of the costochondral junctions), craniotabes (areas of softening of the skull) and thickening of the wrists and ankles caused by metaphyseal widening. Proximal myopathy occurs in both children and adults, especially when vitamin D deficiency is prominent. Bone pain, often mistaken for osteoarthritis in adults, may be due to stress fractures that fail to heal (Looser’s zones), often in the pelvis and medial side of the femur.

Biochemical testing should include measurement of serum levels of ionised calcium, which may be low or normal, parathyroid hormone (PTH), which may be high (secondary hyperparathyroidism) or normal, and vitamin D, which is generally < 50 nmol/L (vitamin D insufficiency) and possibly < 30 nmol/L (frankly low).4 A slightly raised level of serum alkaline phosphatase is an easily detected and relatively sensitive marker of the mineralisation defect of osteomalacia. Most laboratories report total alkaline phosphatase level, comprising both liver and bone isoenzymes. Although there are specific assays for bone alkaline phosphatase, the diagnosis of a mineralisation defect is usually considered when the alkaline phosphatase level is raised but other liver enzymes are normal. However, as bone alkaline phosphatase levels rise with age, it is important to differentiate pathological and physiological changes.

Treatment comprises calcium supplementation combined with replacement vitamin D, if this is deficient. Dietary calcium is effective, but it is easier to consume the required quantity of calcium (1–2 g in adults, 0.5–1 g in children) in tablet form, as calcium carbonate or the better-absorbed calcium citrate.5 Vitamin D replacement with ergocalciferol (two to three 1000 IU capsules daily) is appropriate even if sunlight is available. Surprisingly, this preparation is not supported by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Lower doses of vitamin D are available in many other over-the-counter preparations. The active form of vitamin D, calcitriol (0.25–1 μg daily), is used if renal function is compromised.

Rickets and osteomalacia may also result from a deficient supply of phosphate to the growth plate and bone surface. As dietary phosphate, unlike calcium, is rarely deficient, the cause is usually excess phosphate excretion in the urine. The causes include a range of disorders of phosphate transport in the kidney:6

Childhood-onset autosomal dominant hypophosphataemic rickets (ADHR) is associated with activating mutations in the gene encoding fibroblast growth factor (FGF-23), which acts as a hormone to increase renal phosphate excretion.

X-linked hypophosphataemic rickets is associated with mutations that inactivate the product of the PHEX gene (phosphate-regulating gene with homologies to endopeptidase on the X chromosome).

In adults, oncogenic osteomalacia (also known as tumour-induced osteomalacia) is caused by benign, or occasionally malignant, mesenchymal tumours that secrete factors that lead to phosphate wasting and a phenotype similar to X-linked hypophosphataemic rickets.

In the last two conditions, serum levels of fibroblast growth factor are also raised, but the exact relationships between renal tubular phosphate handling, fibroblast growth factor and PHEX function and stability are unknown.

In view of the inherited nature of many forms of hypophosphataemic rickets, a family history is essential. The principal biochemical abnormalities are a low plasma phosphate level and increased renal phosphate excretion. The serum phosphate reference range is increased in neonates and falls through childhood, with a second peak at puberty. Under the influence of sex hormones, it then falls to reach adult values by age 15 to 18 years.7 Prolonged sample storage may increase the measured plasma phosphate level. Although relative calcitriol deficiency is evident in hypophosphataemic rickets, this feature is not used in establishing the diagnosis because of the complexity of the assay. Markers of bone turnover, such as serum alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin levels, are usually raised. Calcium biochemistry is relatively normal, apart from secondary or tertiary hyperparathyroidism, the latter developing as a result of phosphate-therapy-induced hypocalcaemia. Nephrocalcinosis may occur and should be screened for by renal ultrasound examination. If cancer-induced osteomalacia is suspected, then bone scanning using a radiolabelled bisphosphonate tracer (which is deposited in areas of increased bone turnover), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) may be needed to locate the tumour.

The aim of treatment is to correct or prevent bone deformity by supplying sufficient phosphate to mineralising surfaces to maintain bone structure. This is achieved with regular doses of oral phosphate (1–3 g daily in adults and 500 mg–1.5 g in children, in four to five doses), and calcitriol (1–2 μg daily in adults and 30–70 ng/kg daily in children).8 In tumour-induced osteomalacia, surgical removal of tumours leads to prompt biochemical remission.

Lytic and sclerotic bone disease is treated with monthly intravenous doses of bisphosphonate, either pamidronate (60–90 mg) or zoledronic acid (4 mg). This directly inhibits osteoclast-mediated bone resorption.9 If hypercalcaemia is present, a saline infusion is also used to increase renal calcium excretion (see below). In addition to treatment directed at the bone itself, the primary cancer and its metatases should be treated as required by localised surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or endocrine therapy.

Paget’s disease is a localised disorder of osteoclast overactivity, which leads to the formation of mechanically ineffective woven or “repair” bone, rather than lamellar bone.10 This results in bending of long bones, with compensatory periosteal expansion and cortical thickening (Box 3B). Some variants of the disease are caused by a mutation in the sequestosome gene.11 In the past, a slow-virus origin has been postulated, perhaps associated with close contact with dogs, but this suggestion remains controversial.12

The disease occurs in people of northern European background.13 The condition is progressive through life but does not usually cause symptoms until mid or later life (see case report,Box 4).

Symptoms comprise localised deformity, bone pain and fracture, including stress fracture (Box 3B). Careful examination of affected areas, noting deformity, temperature of the overlying skin and localised bone pain suggestive of stress fracture are important. Paraplegia, deafness and high output heart failure occur occasionally.

Bone scanning with a radiolabelled bisphosphonate tracer of bone activity is useful to detect foci of disease in other bones and should be used in preference to radiological skeletal survey. However, radiology is required to determine the precise extent and severity of the disease and to exclude metastatic cancer.

Biochemical evaluation is directed at measuring markers of bone formation (serum alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin) and resorption (urine deoxypyridinoline to creatinine ratio) and excluding other bone disorders, such as cancer, osteomalacia and hyperparathyroidism.14 The single most practically useful test for diagnosis is measurement of serum alkaline phosphatase level, which may be very high, although occasionally within the reference range.

In primary hyperparathyroidism, plasma levels of ionised calcium and PTH are high relative to each other and must be measured in the same sample15 (see case report,Box 5). In cancer-induced hypercalcaemia, PTH is suppressed, but PTH-related peptide levels may be elevated.16 Renal function should be measured because of the potential effect of hypercalcaemia in reducing kidney function. Bone involvement should be assessed by measuring markers of bone turnover, and vitamin D deficiency excluded, given that it may be associated with primary hyperparathyroidism.

The acute management of hypercalcaemia is the same irrespective of its cause. It comprises:

intravenous saline to expand the extracellular volume and obviate calcium resorption in the proximal renal tubules, which accompanies a volume-contracted state; and

intravenous bisphosphonate therapy to reduce osteoclast activity, which lowers calcium level over about 4 days.17

Diuretics should be used only if the patient becomes volume overloaded. There is no place for forced saline diuresis.

Definitive therapy depends on the aetiology. For example, in myeloma, prednisone (40 mg daily) is effective in reducing osteoclast activity. In cancer-induced hypercalcaemia, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or endocrine therapy may be required. Primary hyperparathyroidism is best treated by parathyroidectomy.18 The exact indications for surgery remain controversial as there are no randomised controlled trial data. Presurgery localisation is being re-examined, but an old truism is that “the most important localisation is that of an experienced parathyroid surgeon”. There is no place for the “occasional parathyroidectomist”.

This complex form of metabolic bone disease occurs in patients with chronic renal failure and is usually managed by renal physicians. The clinical manifestations of bone pain and ectopic calcification occur in the dialysis phase of the illness. Early manifestations are secondary hyperparathyroidism and osteoporosis, which can be managed by calcium and calcitriol supplementation.19

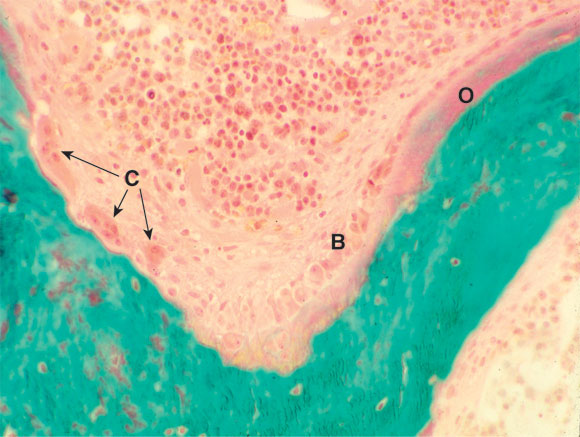

1: Bone remodelling unit

Section of bone, showing a bone remodelling unit with osteoclasts (C) resorbing bone and osteoblasts (B) laying down osteoid (O), which is beginning to mineralise. (Courtesy of Professor S Ott, University of Washington, Seattle, USA. http://courses.washington.edu/bonephys).

2: Regulation of calcium and phosphate homoeostasis

Parathyroid hormone

|

|||||||||||

Vitamin D

|

|||||||||||

Phosphatonin

|

|||||||||||

* Parathyroid hormone (PTH) can increase both bone formation and bone resorption, depending on calcium requirements and blood levels. † 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3. |

|||||||||||

3: Anatomical abnormalities in bone disorders

A: Bowing of the tibia (genu varum) in childhood rickets, caused by poor structural integrity of osteomalacic bone.

B: Paget’s disease of the tibia, showing typical sclerotic and lytic areas (S), thickened expanded cortex (C), and a stress fracture (F). Stress fractures can be very difficult to heal and may form the site of a complete fracture.

4: Case report — a complication of Paget’s disease

Presentation: A 75-year-old woman presented with pain in her tibia, which had become curved over some years. Her father, who was from the north of England, had a similar problem as he got older. Paget’s disease was diagnosed, and treatment with a bisphosphonate begun. However, the pain worsened and became localised to a tender spot on the medial aspect of the tibia.

Investigations: Biochemical testing showed low levels of ionised calcium (0.95 mmol/L; reference range [RR], 1.12–1.32 mmol/L) and 25-hydroxyvitamin D (15 nmol/L; RR, > 40 nmol/L), and a raised level of parathyroid hormone (11.0 pmol/L; RR, 0.9–9.0 pmol/L).

What is the diagnosis?

The patient has developed a stress fracture in the pagetic bone. This has occurred because the abnormal woven bone of Paget’s disease can develop fatigue failure.

She also has secondary hyperparathyroidism due to extracellular calcium deficiency. This can occur during therapy with bisphosphonates, as calcium is no longer released by the overactive osteoclasts and enters pagetic bone as part of the remineralisation process.

The patient is also vitamin D deficient and so has reduced intestinal absorption of calcium.

How should the disease be managed?

Therapy with calcium (600 mg three times daily) and ergocalciferol (2000 IU daily) was begun, in addition to the bisphosphonate. The secondary hyperparathyroidism and bone pain disappeared over 6 months.

Supportive therapy included pain relief and reduced weight bearing through use of a walking stick.

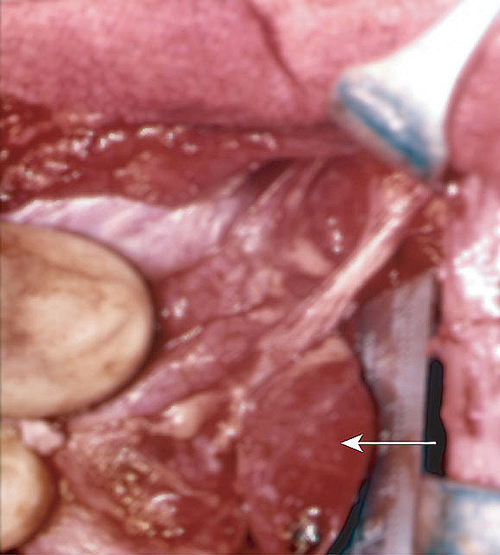

5: Case report — investigating hypercalcaemia

A single parathyroid nodule (arrow) is found at surgery in 85% of cases of hyperparathyroidism. Single nodules are unlikely to recur. Remaining cases are due to hyperplasia of more than one gland, which often recurs.

Presentation: A 60-year-old retired nurse presented with a fracture of the T11 vertebra that occurred on getting out of bed. At age 45, she had had a left mastectomy for breast cancer. No lymph node involvement was found. She had long-standing hypertension with early renal decompensation. Plasma calcium level was raised (3.3 mmol/L; reference range [RR], 2.25–2.55 mmol/L), as were parathyroid hormone level (18.0 pmol/L; RR, 0.9–9.0 pmol/L) and creatinine level (220 μmol/L; RR, 50–95 μmol/L).

What was the most efficient way to diagnose the cause of the hypercalcaemia?

Careful imaging of the fracture was needed to determine whether there was evidence of cancer metastasis.

Measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) was worthwhile at the same time to assess the presence of osteoporosis at other skeletal sites. This would suggest a systemic rather than localised disorder.

A bone scan using technetium-99m-labelled bisphosphonate might reveal other hot spots, suggesting metastases or fractures that would require radiological evaluation.

Biochemical testing was the definitive test, as the plasma parathyroid hormone level was raised at the time of the hypercalcaemia. These results indicate that the patient had developed primary hyperparathyroidism, which had led to the deterioration in renal function.

What treatment should be offered?

Supportive treatment and pain relief were given for the fracture. The patient had a semi-urgent parathyroidectomy. A left upper parathyroid adenoma was removed, weighing 300 mg. Her recovery was uneventful, and creatinine level returned to its previous value of 150 μmol/L. Once the fracture had healed bisphosphonate therapy was considered.

- 1. Thacher TD, Fischer PR, Pettifor JM, et al. A comparison of calcium, vitamin D, or both for nutritional rickets in Nigerian children. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 563-568.

- 2. Devine A, Wilson SG, Dick IM, Prince RL. Effects of vitamin D metabolites on intestinal calcium absorption and bone turnover in elderly women. Am J Clin Nutr 2002; 75: 283-288.

- 3. Thomas MK, Lloyd-Jones DM, Thadhani RI, et al. Hypovitaminosis D in medical inpatients. N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 777-783.

- 4. Malabanan A, Veronikis IE, Holick MF. Redefining vitamin D insufficiency. Lancet 1998; 351: 805-806.

- 5. Recker RR. Calcium absorption and achlorhydria. N Engl J Med 1985; 313: 70-73.

- 6. Jan de Beur SM, Levine MA. Molecular pathogenesis of hypophosphatemic rickets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87: 2467-2473.

- 7. Lockitch G, Halstead AC, Albersheim S, et al. Age- and sex-specific pediatric reference intervals for biochemistry analytes as measured with the Ektachem-700 analyzer. Clin Chem 1988; 34: 1622-1625.

- 8. Friedman NE, Lobaugh B, Drezner MK. Effects of calcitriol and phosphorus therapy on the growth of patients with X-linked hypophosphatemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1993; 76: 839-844.

- 9. Major PP, Cook R. Efficacy of bisphosphonates in the management of skeletal complications of bone metastases and selection of clinical endpoints. Am J Clin Oncol 2002; 25 (6 Suppl 1): S10-S18.

- 10. Lyles KW, Siris ES, Singer FR, Meunier PJ. A clinical approach to diagnosis and management of Paget’s disease of bone. J Bone Miner Res 2001; 16: 1379-1387.

- 11. Hocking LJ, Lucas GJ, Daroszewska A, et al. Domain-specific mutations in sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) cause familial and sporadic Paget’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 2002; 11: 2735-2739.

- 12. Ooi CG, Walsh CA, Gallagher JA, Fraser WD. Absence of measles virus and canine distemper virus transcripts in long-term bone marrow cultures from patients with Paget’s disease of bone. Bone 2000; 27: 417-421.

- 13. van Staa TP, Selby P, Leufkens HG, et al. Incidence and natural history of Paget’s disease of bone in England and Wales. J Bone Miner Res 2002; 17: 465-471.

- 14. Alvarez L, Guanabens N, Peris P, et al. Usefulness of biochemical markers of bone turnover in assessing response to the treatment of Paget’s disease. Bone 2001; 29: 447-452.

- 15. Glendenning P, Gutteridge DH, Retallack RW, et al. High prevalence of normal total calcium and intact PTH in 60 patients with proven primary hyperparathyroidism: a challenge to current diagnostic criteria. Aust N Z J Med 1998; 28: 173-178.

- 16. Walls J, Ratcliffe WA, Howell A, Bundred NJ. Parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related protein in the investigation of hypercalcaemia in two hospital populations. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1994; 41: 407-413.

- 17. Grill V, Murray RM, Ho PW, et al. Circulating PTH and PTHrP levels before and after treatment of tumor induced hypercalcemia with pamidronate disodium (APD). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1992; 74: 1468-1470.

- 18. Davies M, Fraser WD, Hosking DJ. The management of primary hyperparathyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002; 57: 145-155.

- 19. Bardin T. Musculoskeletal manifestations of chronic renal failure. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2003; 15: 48-54.

Abstract

Rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults are caused by undermineralisation of bone, which increases its susceptibility to bending and fracture; treatment is with calcium, vitamin D or phosphate, depending on the specific mineral or vitamin deficiency.

In Paget’s disease, osteoclasts are overactive and produce woven or “repair” bone, which is mechanically weaker than lamellar bone; treatment is with antiresorptive bisphosphonate drugs.

Cancers can produce bone lysis through direct spread within the skeleton or production of endocrine parathyroid hormone-like factors; treatment is with a bisphosphonate, plus appropriate therapy for the cancer.

Cancer can also produce hypercalcaemia if the capacity of the kidneys to excrete the calcium dissolved from bone is exceeded; treatment is with saline infusion to increase excretion and a bisphosphonate.

Primary hyperparathyroidism is the other common cause of hypercalcaemia and is usually associated with a single parathyroid adenoma; it is best treated with parathyroidectomy.

Hypocalcaemia may result from severe decrease in calcium absorbed or lack of parathyroid action; both are treated with calcium and vitamin D (ergocalciferol or calcitriol).