Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, was introduced into Australia in 1999 for the treatment of alcohol dependence within a comprehensive treatment program. Alcohol use stimulates opioid receptors and releases endorphins in the brain,1,2 and naltrexone is thought to reduce the incentive to drink and decrease craving by blocking these pleasurable "high" effects of alcohol.3,4

The efficacy of naltrexone as a treatment for alcohol dependence has been documented in several double-blind, placebo-controlled studies.3,4,5-9 It has been found to significantly reduce the rate of relapse into heavy drinking and the number of drinking days.2,3 These predominantly North American studies also used comprehensive psychosocial programs which included coping skills supportive therapy,5,6 relapse prevention,3,4 intensive manual-guided cognitive behavioural therapy,7 adjunctive psychosocial interventions,8 and/or weekly group therapy.9

A key question is whether naltrexone is beneficial when only a modest level of supportive or psychosocial therapy is available, a reality in many clinical settings. We aimed to determine the safety and effectiveness of naltrexone in patients of both sexes in a standard clinical setting without extensive psychosocial interventions. We also examined levels of compliance and determined whether naltrexone significantly improves medical and psychosocial outcomes.

After a full history and clinical examination, patients who fulfilled entry criteria completed several self-rating questionnaires, including the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT),10 CAGE,11 and the Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SADQ).12 Craving was measured by the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS),13 and depression was assessed by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).14 Blood was taken for routine full blood count and liver function tests.

The major outcomes reported include relapse rates (defined as drinking to previous heavy levels, in excess of National Health and Medical Research Council recommendations15), time in days to first relapse, and subjective reports of side effects. Patients who did not attend follow-up and whose outcome was unknown were considered to have dropped out of the trial.

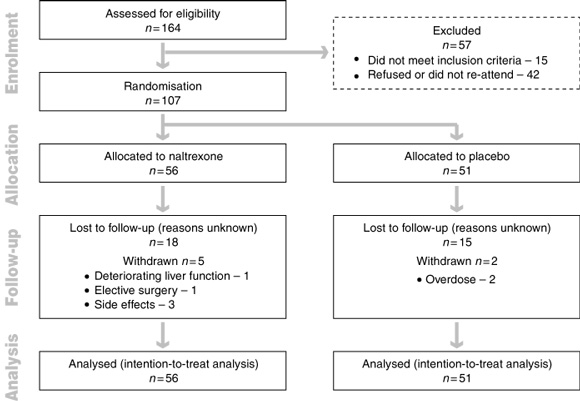

A diagram of the flow of participants from enrolment to analysis is given in Box 1. The 107 participants (74 men and 33 women) had a mean age of 44.8 years (95% CI, 42.8–46.8; range, 23–70 years). There were no significant differences in age, sex ratio or demographic characteristics between the patients in the naltrexone and placebo groups (including marital status, educational level, and employment history) (data not shown).

All patients underwent detoxification before commencing the trial; 76 (71%) underwent home detoxification and 31 (29%) were admitted to a detoxification unit. All abstained from alcohol for a mean of 11.7 days (range, 7–51 days).

Mean weekly alcohol intake at baseline was 1200.3 g (95% CI, 1075.0–1365.7) for naltrexone and 1152.2 g (95% CI, 1026.9–1277.5 g) for placebo (equivalent to 17 standard drinks per day), indicating moderate to severe alcohol dependence (Box 2). On average, alcohol-related problems had emerged in the patients' early 30s, about 10 years after the onset of heavy drinking. The mean duration of alcohol dependence was 14.1 years (95% CI, 10.9–17.3). About 72% had been to Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and 55% had undergone residential detoxification. Seventy-five per cent had a family history of alcoholism, 77% a history of blackouts, 55% of drink-driving charges and 36% of violence or crime.

Regardless of treatment response, 67 patients (63%) attended treatment for 12 weeks: 33/56 (59%) taking naltrexone and 34/51 (67%) taking placebo. Subsequently, 30/67 patients (45%) chose to continue taking naltrexone for a further 3 months of treatment: 16 of those initially taking naltrexone and 14 of those given placebo.

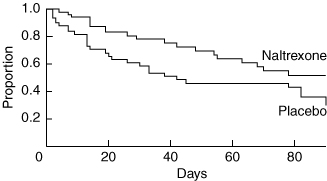

In absolute numbers, fewer patients taking naltrexone (19/56; 33.9%) relapsed compared with those taking placebo (27/51; 52.9%) (P = 0.047). The odds of relapsing were twice as likely for placebo compared with naltrexone (odds ratio [OR], 2.2; 95% CI, 1.0–4.8). On an intention-to-treat basis, the Kaplan–Meier survival curve (Box 3) also showed that the relapse rate was significantly lower in the naltrexone group compared with the placebo group (log-rank test, χ21 = 4.15; P = 0.042). Overall, the relative risk of relapsing was 0.55 for the naltrexone group compared with the placebo group (95% CI, 0.3–0.9). The median time to relapse was greater for patients in the naltrexone group compared with the placebo group (90 v 42 days, respectively). Time-dependent Cox regression analysis confirmed that the relapse-preventing effect of naltrexone was most marked during the first 42 days (P = 0.012).

In comparison with baseline, mean alcohol consumption fell significantly at 3 months, but mean consumption at 3 months did not differ across treatment groups (Box 4). Mean craving scores also decreased significantly from baseline to 3 months. Again, there was no significant difference between the two treatment groups.

At initial assessment, high depression scores were common, 41/107 (38.3%) of patients having a Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score greater than 20; 35.7% of patients taking naltrexone (mean score, 17.4; 95% CI, 14.4–20.4) and 41.2% of patients taking placebo (mean score, 18.4; 95% CI, 15.6–21.2) presented with high BDI scores (Box 4). At 3 months, 22% of patients taking naltrexone had high BDI scores (mean, 10.0; 95% CI, 6.3–13.7) compared with 3% of patients taking placebo (mean, 5.9; 95% CI, 3.8–8.0; P = 0.023). This result should be interpreted with caution, however, as patients with high BDI scores were nearly nine times more likely to drop out of treatment, in comparison with those with BDI scores within the normal range (OR, 8.7; 95% CI, 6.9–34.4; P = 0.003). This drop-out rate did not differ across treatment groups.

One patient taking naltrexone was withdrawn from the trial before having elective surgery, and two patients taking placebo were withdrawn after hospitalisation for drug overdoses. Despite 28 days' abstinence, deterioration in liver function was observed in one of three patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in this patient rose from 132 U/L to 185 U/L within the first week. After the code was broken and naltrexone stopped, the ALT level rose further to 412 U/L at the end of the second week and then gradually normalised over subsequent months. Liver function test-results improved in two other patients with chronic hepatitis C who remained in the trial.

Abnormal γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT) levels (> 65 U/L) were observed in 30% of patients on entry into the trial: 21/56 patients (37.5%) taking naltrexone and 11/51 (21.5%) taking placebo. At 3 months only 9/58 (15.5%) of the total patient group assessed had abnormal GGT levels: 5/28 (17.9%) of those taking naltrexone and 4/30 (13.3%) of those taking placebo (Box 4).

Survival analysis showed that naltrexone 50 mg/day for 3 months was significantly more effective than placebo in preventing relapse in a mixed-sex group of alcohol-dependent patients. The beneficial effect of naltrexone was observed in the context of a standard medical outpatient clinic and was most marked during the first six weeks, suggesting a rapid onset of effect. These findings are similar to those of other double-blind, placebo-controlled studies where survival curves for time to first relapse with naltrexone or placebo showed the most marked divergence during the first 40 days of treatment.3,5,7-9

Our study follows a "real-life" treatment approach to alcohol dependence by providing pharmacotherapy and making available optional psychosocial supportive therapy in a conventional outpatient clinical setting. Counselling was taken up by only a third of our patients, and the proportion of patients who participated in counselling did not differ between the naltrexone and placebo groups. Patients who accepted counselling had higher retention rates, but relapse rates in those who did and those who did not participate in counselling showed no significant difference.

We suggest caution in generalising these results. The trial involved a relatively small number of patients. The sample size of 107 patients was less than required by the power calculation (118 patients). This was because recruitment became difficult after Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme listing of acamprosate (Campral; Alphapharm) and naltrexone (Revia; Orphan), which meant that they were available to the public without participation in clinical trials. Additionally, preliminary analysis showed statistically significant results consistent with those reported in previous studies.3,5 It is important to note, however, that some of the non-significant results reported here may be due to lack of statistical power.

Our patients were advised to strive for abstinence and all received repeated and regular medical advice and support at each follow-up session. Advice was standardised and provided by the same physician to all the patients throughout our trial. Moreover, the advice to abstain from alcohol was reinforced with objective evidence of improvement (eg, in γ-glutamyltransferase levels and mean cell volume) for those who abstained. This could account for the significant reduction in the average alcohol intake by 84% in both the naltrexone- and placebo-treated groups. Kristenson similarly found that counselling and repeated feedback of results of measurement of γ-glutamyltransferase level led to improved outcomes in middle-aged heavy drinkers, including those with alcohol dependence.16

Naltrexone blocks some of the rewarding effects of alcohol, but it does not significantly prevent subjects from drinking any alcohol. The urge to drink more is controlled, so that studies have shown that patients taking naltrexone drink less and have increased intervals between relapses into heavy drinking.3,4 Our results are consistent with these findings.

Apart from the higher incidence of headaches in patients in the placebo group, we found no significant difference between naltrexone and placebo in reported side effects, which were generally mild. Naltrexone is reported to have the potential to cause liver damage when given in excessive doses.17 High doses of naltrexone were not prescribed in our trial. However, as one of three patients with chronic hepatitis C infection experienced liver function deterioration, we urge caution when administering naltrexone to such patients.

Despite the patients' high depression scores on entry into the trial, and depression being listed as one of the side effects of naltrexone, depression scores improved significantly during treatment in both the naltrexone and placebo groups. However, a significantly greater proportion of patients in the naltrexone group had Beck Depression Inventory scores exceeding 20 at 3 months. Hence, ongoing monitoring of depression in alcohol-dependent patients is advisable.

In conclusion, our results were obtained within the context of a medical outpatient clinic where counselling was available but taken up by only a third of patients. Unlike previous studies, we have shown that naltrexone, with adjunctive medical advice, is effective in the treatment of alcohol dependence irrespective of whether it is accompanied by formal psychosocial interventions.

2: Patients' baseline alcohol history and clinical characteristics related to alcohol. Data are given as means (95% CI)

Naltrexone (n = 56) |

Placebo (n = 51) |

Total (n = 107) |

|||||||||

Age of onset of drinking |

23.0 |

22.2 |

22.8 |

||||||||

Age of onset of drinking problems |

31.0 |

30.6 |

30.8 |

||||||||

Duration of drinking problems |

14.5 |

13.6 |

14.1 |

||||||||

Baseline alcohol intake (g/week) |

1200.3 |

1152.2 |

|||||||||

AUDIT score |

27.6 |

28.6 |

|||||||||

CAGE score |

3.4 |

3.3 |

|||||||||

SADQ score |

22.5 |

24.5 |

|||||||||

AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test |

|||||||||||

4: Patient outcomes at 3 months — naltrexone and placebo groups

Baseline |

3 Months |

||||||||||

Naltrexone |

Placebo |

Naltrexone |

Placebo |

||||||||

Mean alcohol intake |

1200.3 |

1152.2 |

162.5* |

228.1* |

|||||||

Mean OCDS craving score |

22.1 |

24.0 |

9.2* |

9.1* |

|||||||

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) |

|||||||||||

Proportion with BDI scores > 20 |

20/56 |

21/51 |

7/32† |

1/32 |

|||||||

Mean BDI score |

17.4 |

18.4 |

10.0* |

5.9* |

|||||||

γ-Glutamyltransferase U/L (GGT) |

|||||||||||

Proportion with GGT level > 65 U/L |

21/56 |

11/51 |

5/28 |

4/30 |

|||||||

Mean GGT level (95% CI) |

49.2 |

40.1 |

26.4* |

28.5* |

|||||||

Mean aspartate aminotransferase level (U/L) |

29.2 |

26.5 |

23.9* |

22.3* |

|||||||

Mean alanine aminotransferase level (U/L) |

34.2 |

29.5 |

24.1* |

22.6* |

|||||||

Mean cell volume (MCV) (fL) |

|||||||||||

Proportion with MCV > 100 fL |

12/52 |

9/50 |

3/27 |

2/30 |

|||||||

Mean MCV |

95.2 |

95.8 |

92.2 |

89.7 |

|||||||

* Statistically significant difference from baseline. † Statistically significant difference between naltrexone and placebo. OCDS = Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale. |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Received 25 June 2001, accepted 28 February 2002

- Noeline C Latt1

- Stephen Jurd

- Jennie Houseman3

- Sonia E Wutzke4

- 1 Faculty of Medicine, University of Sydney, and Herbert Street Drug and Alcohol Clinic, Royal North Shore Hospital, St Leonards, NSW.

- 2 Faculty of Medicine, University of Sydney, and Drug Health Services, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, NSW.

We acknowledge financial support from Northern Sydney Health, Orphan Australia, Du Pont Pharma and the Kim and Kris Morris Trust Fund for Drug & Alcohol Services. We are grateful to Professor John B Saunders and Professor Charles O'Brien for their helpful comments. We are indebted to Professor Don McNeil and Ms Shan Shan Shanley Chong, Macquarie University, Department of Statistics, for statistical analysis of data. We wish to thank Dr Harding Burns for advice and encouragement.

None declared.

- 1. Hynes MD, Lochner MA, Bemis K, et al. Chronic ethanol alters the receptor binding characteristics of the delta opioid receptor ligand, D-ala-2-D-Leu 5-Enkephalin in mouse brain. Life Sci 1983; 33: 2331-2337.

- 2. Hyytia P, Sinclair JD. Responding for oral ethanol after naloxone treatment by alcohol preferring AA rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1993; 17: 631-636.

- 3. Volpicelli JR, Alterman AI, Hayashida M, et al. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49: 876-880.

- 4. Volpicelli JR, Rhines KC, Rhines JS, et al. Naltrexone and alcohol dependence: role of subject compliance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997; 54: 737-742.

- 5. O'Malley SS, Jaffe AJ, Chang G, et al. Naltrexone and coping skills therapy for alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49: 881-887.

- 6. O'Malley SS, Croop RS, Wroblewski JM, et al. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a combined analysis of two trials. Psychiatr Ann 1995; 25: 681.

- 7. Anton RF, Moak DH, Waid LR, et al. Naltrexone and cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment of outpatient alcoholics: results of a placebo controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1999; 156: 1758-1764.

- 8. Chick J, Anton R, Checinski K, et al. A multicentre randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence or abuse. Alcohol Alcohol 2000; 35: 587-593.

- 9. Morris PLP, Hopwood M, Whelan G, et al. Naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial. Addiction 2001, 96: 1565-1573.

- 10. Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor T, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption – II. Addiction 1993; 88: 791-803.

- 11. Mayfield D, Mcleod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry 1974; 131: 1121-1123.

- 12. Stockwell T, Hodgson R, Edwards G, et al. The development of a questionnaire to measure severity of alcohol dependence. Br J Addiction 1979; 77: 79-87.

- 13. Anton RF. Obsessive-compulsive aspects of craving: development of the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale. Addiction 2000; 95 (Suppl 2): S211-S217.

- 14. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4: 561-571.

- 15. National Health and Medical Research Council. Is there a safe level of daily consumption of alcohol for men and women? Canberra: NHMRC, 1992.

- 16. Kristenson H. Methods of intervention to modify drinking patterns in heavy drinkers. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in alcoholism, Vol 5. New York: Plenum Publishing, 1987: 403-423.

- 17. Product Information on Revia (Naltrexone hydrochloride; Orphan) approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration, 6 January 1999.

Abstract

Objectives: To determine whether naltrexone is beneficial in the treatment of alcohol dependence in the absence of obligatory pyschosocial intervention.

Design: Multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Hospital-based drug and alcohol clinics, 18 March 1998 – 22 October 1999.

Patients: 107 patients (mean age, 45 years) fulfilling Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th edition) criteria for alcohol dependence.

Interventions: Patients with alcohol dependence were randomly allocated to naltrexone (50 mg/day) or placebo for 12 weeks. They were medically assessed, reviewed and advised by one physician, and encouraged to strive for abstinence and attend counselling and/or Alcoholics Anonymous, but this was not obligatory.

Main outcome measures: Relapse rate; time to first relapse; side effects.

Results: On an intention-to-treat basis, the Kaplan–Meier survival curve showed a clear advantage in relapse rates for naltrexone over placebo (log-rank test, χ21 = 4.15; P = 0.042). This treatment effect was most marked in the first 6 weeks of the trial. The median time to relapse was 90 days for naltrexone, compared with 42 days for placebo. In absolute numbers, 19 of 56 patients (33.9%) taking naltrexone relapsed, compared with 27 of 51 patients (52.9%) taking placebo (P = 0.047). Naltrexone was well tolerated.

Conclusions: Unlike previous studies, we have shown that naltrexone with adjunctive medical advice is effective in the treatment of alcohol dependence irrespective of whether it is accompanied by psychosocial interventions.