Dissecting haematoma of the oesophagus is a rare, relatively benign condition that mimics much more common and serious illnesses.1 The onset of sudden severe retrosternal chest pain in an elderly person, who often has other cardiovascular risk factors, may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of cardiac pain. In some cases, subsequent thrombolytic treatment has led to fatalities. In others, the appearance of intramural thrombus on radiological or endoscopic views has been mistaken for advanced oesophageal malignancy or rupture.2,3

Because of the rarity of dissecting haematoma of the oesophagus, diagnosis depends on an accurate history and a high index of suspicion. Those affected are usually women (relative risk, 1.8 — the inverse to the male bias in cardiovascular and malignant oesophageal disease),3 elderly (median age, 63 years),3 and not uncommonly taking anticoagulant or antiplatelet agents. Patients present with a variable combination of chest pain (usually sudden in onset and of short duration), haematemesis (mainly small volume and occurring after the pain), and dysphagia and/or odynophagia. In one meta-analysis, 99% of patients had at least one of these symptoms, and 32% had all three.3 In particular, the presence of dysphagia or odynophagia in a patient otherwise thought to have angina or myocardial infarction should prompt oesophageal imaging before administration of fibrinolytic agents. A simple test is to ask the patient to take a sip of water as part of the examination. If this exacerbates symptoms or unmasks new ones, a more specific focus on the possibility of oesophageal abnormality is warranted.

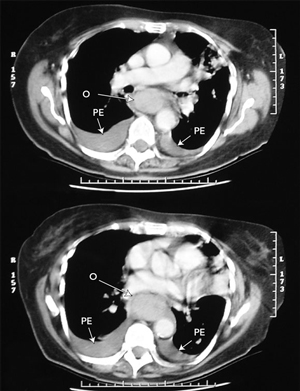

Dissecting haematoma of the oesophagus has a typical appearance on imaging.4,5 Barium swallow shows a long, smooth tubular filling defect in the lumen of the oesophagus, sometimes with the dissection space filled with a stripe of contrast (the “double-barrelled oesophagus”). As the dissection most commonly occurs along the posterior wall, the lateral view is most useful. Computed tomography demonstrates an obliterated lumen with thickening of the wall. This extends over a long length of the oesophagus, and can mimic oesophageal rupture or extensive malignancy. The haematoma is large, fluctuant, and blue or purplish when viewed at endoscopy. Delayed endoscopy shows a long ulcer, where the overlying mucosa has sloughed, followed by rapid regeneration and an ultimately normal appearance.3

For a condition with such dramatic presentation, the natural history is refreshingly benign. The best intervention is non-intervention: the haematoma almost always resolves, and full oesophageal function is restored. Intravenous hydration, supplemented by parenteral or enteral nutrition in appropriate cases, is usually all that is needed. Anti-ulcer medications have no proven benefit.3 Surgery is indicated if there is uncontrolled arterial bleeding, or if the partial rupture has been converted to a full thickness tear through endoscopy.3 A further indication for surgery is a focus of infection within the false lumen, preventing healing. In two such cases, endoscopic division of the overlying mucosal flap resulted in complete resolution of fever, odynophagia and neutrophilia.1,6 Unfortunately, aggressive intervention has led to fatalities.3

- 1. Bak YT, Kwon OS, Yeon JE, et al. Endoscopic treatment in a case of dissection of the oesophagus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998; 10: 969-972.

- 2. Meulman N, Evans J, Watson A. Spontaneous intramural haematoma of the oesophagus: a report of three cases and review of the literature. Aust N Z J Surg 1994; 64: 190-193.

- 3. Cullen SN, McIntyre AS. Dissecting intramural haematoma of the oesophagus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 12: 1151-1161.

- 4. Yuen EHY, Yang WT, Lam WW, et al. Spontaneous intramural haematoma of the oesophagus: CT and MRI appearances. Australas Radiol 1998; 42: 139-142.

- 5. Clark W, Cook IJ. Spontaneous intramural haematoma of the oesophagus: radiologic recognition. Australas Radiol 1996; 40: 269-272.

- 6. Murata N, Kuroda T, Fujino S, et al. Submucosal dissection of the oesophagus: a case report. Endoscopy 1991; 23: 95-97.

None identified.