According to the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (hereafter, the Royal Commission), Australian residential aged care (RAC) inadequately caters to the physical, social and psychological needs of older people. The Royal Commission states that aged care requires “a philosophical shift” that centres on people receiving care and establishes “new foundational principles and core values.”1

We propose reframing RAC as communities within social and ecological communities, to shift away from dominant consumerist approaches to care. Theories of social and environmental justice can then be applied to guide the development of the aged care sector, offering aged care providers and policy makers novel solutions to critical challenges identified by the Royal Commission.

A philosophical shift

The Royal Commission asserted that the sector should deliver care and services that assist people to lead active, self‐determined, meaningful and dignified lives in safe, caring environments,1 but found that systemic flaws and inadequate institutions hindered the sector from achieving this purpose. We maintain that many of these systemic flaws result from an underlying philosophical conception within society of citizens, including RAC residents, as consumers.

Sector regulation claims a commitment to the dignity of service recipients, embedding the concept as the foundational standard of the current Aged Care Quality Standards and featuring it heavily in the Charter of Aged Care Rights.2,3 Standard 1 states, “Being treated with dignity and respect is essential to quality of life. … Organisations are expected to provide care and services that reflect a consumer's social, cultural, language, religious, spiritual, psychological and medical needs.”2 In practice, services delivered across the sector tend to treat RAC residents as consumers rather than with a broader sense of human dignity or personhood. The standards frame dignity as upholding a resident's choices and preferences in all aspects of their care. Currently, an affluent resident in a RAC home that is right for them may be able to attain this vision of dignity and meet all their needs. However, the framing may also compromise holistic human dignity. For example, upholding residents’ consumer rights may mean a RAC provider reduces each resident's services to a list of tasks. This may lead to the perception of residents as no more than a sum of tasks, instead of as people, which, in turn, results in care described as commercialised and transactional, where physical care needs are prioritised over psychological or social needs.1,4

The result of this philosophical reduction of the individual to merely a consumer and ethics to merely transactions is evident in at least three insufficiencies identified by the Royal Commission and other research:

- RAC services tend to neglect the social and cultural needs of residents, often leaving them without access to activities that are meaningful to them.5

- With minimal support from broader social networks, RAC residents are often left voiceless,5 leading to feelings of social isolation, disconnection and loneliness.

- Research conducted parallel to the Royal Commission argues that RAC homes have been predominantly designed without adequate consideration of the surrounding natural environment, leading to homes that hamper connection between residents and the natural world.6

Although it is true that a person will enter aged care with some degree of need for personal and clinical care services, this consumption of services does not account for the totality of the person. The reduction of RAC residents to consumers has led to a sector in which a person's status and role as a member of social and ecological communities can be neglected. It has also contributed to a sector where even clinical care is substandard.5 The Royal Commission concluded that effectively overcoming systemic challenges and achieving the functional purpose of the sector requires a total shift of this philosophical approach.1

A relational philosophy of personhood

Social and environmental justice philosophers argue that relationships to other people, society and nature are in part constitutive of human personhood and are core aspects of human experience and wellbeing.7,8,9 It is true for RAC residents as well as other members of society. However, unlike the latter, RAC residents are dependent on the aged care institution to support their connections to other people, society and nature.

A person's social connections partly constitute their personhood. Humans depend on the formative influences of social relationships from birth and continue to be shaped by reciprocal relations of support as they age.10 Political philosopher Iris Marion Young11 argues that, by being part of a community, a person will develop meanings that directly shape that person's understanding and navigation of the social systems and institutions that compose society. In this way, a community becomes a constitutive component of the people who, at the same time, constitute that community.

Personhood is also partly constituted by a person's environmental connections. Environmental philosopher Aldo Leopold argues that the person is always necessarily and inseparably situated within an ecological community. Ongoing human survival is contingent on the survival of the ecological community of which a person is “a plain member and citizen.”12 The development and direction of human society has been, and continues to be, shaped by membership of the ecological community.

If we accept, then, that human personhood is at least in part constituted by social and ecological relationships, then forced social and ecological detachment can negatively affect physical and psychological wellbeing.6,7 Separating a person from their constituting communities can also be perceived as a separation from purpose or meaning, resulting in a deeper existential suffering. This is described by Kombumerri and Wakka Wakka academic Mary Graham as “a sense of deepest spiritual loneliness and isolation.”13

RAC as a community within social and ecological communities

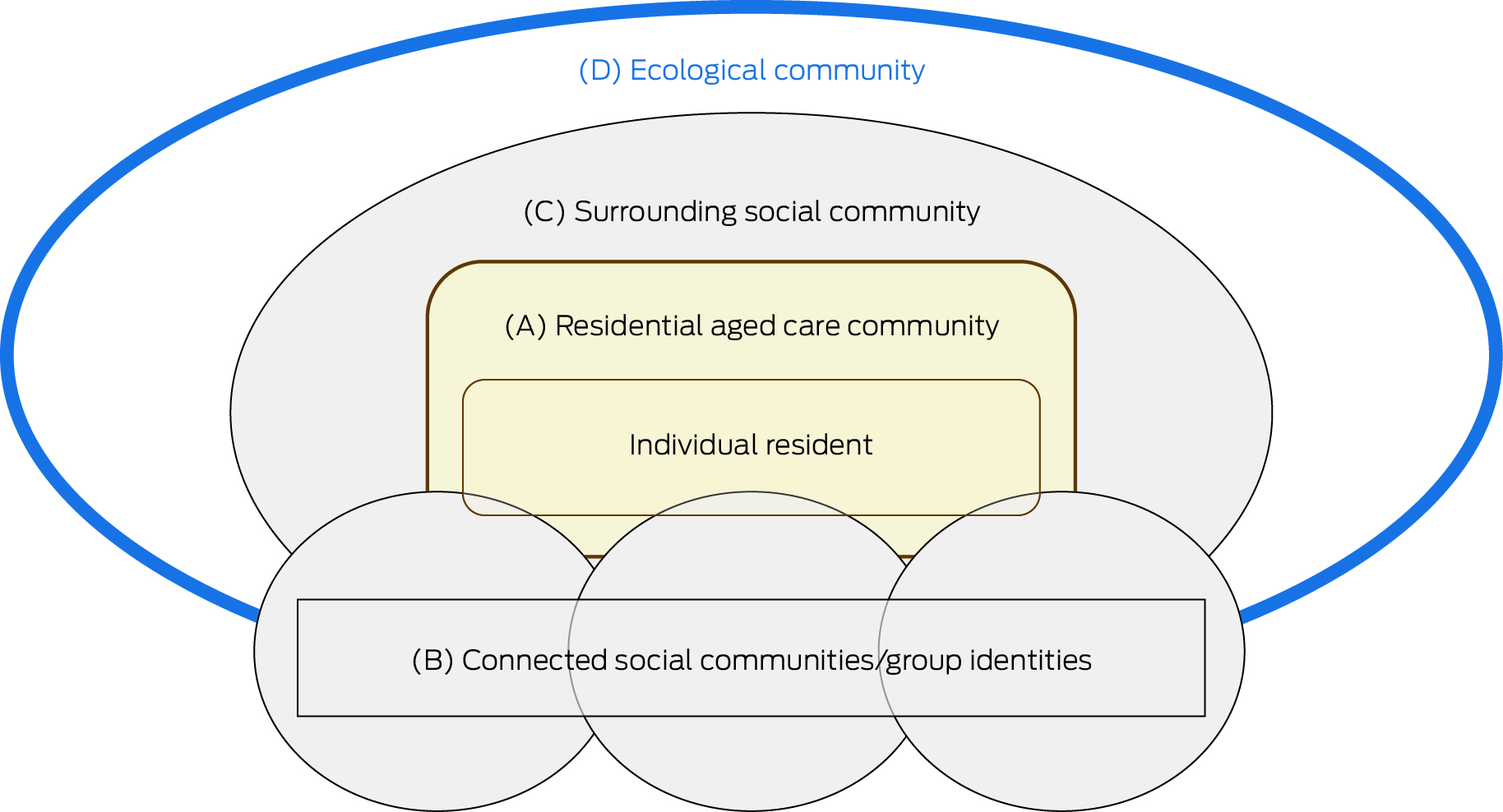

When RAC engages with a resident, they engage not with an isolated individual consumer, but rather with a person who is embedded in and partly constituted by a complex interweaving of social and ecological communities. A RAC home (A in the Box) is a community constituted by the residents of the home, their families and friends, and the staff of the RAC and its institutional governing structures, who are all themselves connected with various other social communities and group identities (B in the Box). This RAC community is always in a surrounding social community (C in the Box), be it a town, a state or a broader group that operates the home (eg, a religious organisation). These social connections shape the expectations and identity of the home and affect how residents, staff and others experience it.

The RAC, both in its constitutive human community and its place‐based built environment, is always in an ecological community (D in the Box). The decisions of the RAC will influence local ecosystems and contribute to global ecological conditions.

A model of aged care that highlights the ethical importance of relationships is not new. Proponents of existing relational approaches suggest that building a person's care and services around their relational roles can ensure that their sense of self is maintained and their care quality is increased.14 Yet, the conception we propose goes further than building clinical care connections. Reframing RAC as a community within communities commits the sector to recognising that it is, itself, shaped by and partly accountable to intersecting community spheres and is composed of humans whose own personhoods are partly community‐constituted.

RAC as the subject of justice

Redefining RAC as a community within communities (the Box) means that the provision of care becomes a matter of justice.

In A theory of justice, John Rawls states that the “subject of justice is the basic structure of society”, that is, how institutions influence how people flourish.15 Iris Marion Young expands on this to include the relational dimension: social justice is the “institutional conditions necessary for the development and exercise of individual capacities and collective communication and cooperation.”11 RAC is part of the basic structure of contemporary society, being a government‐funded and regulated system that provides services to support the everyday lives of older people. RAC homes, as institutions constituted as communities within communities, are therefore subjects of justice. Consequently, the task for RAC homes is to create conditions that support capacities and cooperation of all who fall within their sphere of influence: residents, families, staff and the natural environment.

From this perspective, when RAC promotes the health and wellbeing of residents, it is done so not merely as a matter of service quality and consumption (as in the current consumerist model), but rather as a matter of social and environmental justice.16 This understanding of aged care as a subject of justice aligns with the Royal Commission's recommendations for a system based on a “universal right” to services that provide holistic support in older age.1 Our framework suggests that the community constitution of RAC and its residents should be considered in such a system, but we do not suggest eliminating all elements present in current consumerist approaches. Reframing the sector re‐positions residents as not solely consumers. RAC should give due consideration to community, but residents should also maintain free choice within RAC, including over how their personal and clinical care is conducted.

Implications

The philosophical shift that we are advocating in response to the Royal Commission's request means that lenses of social and environmental justice can be applied that invite novel perspectives on the RAC sector's development and new solutions to the critical challenges identified by the Royal Commission. This reframing may have implications for sector funding and how care is delivered within RAC homes. The implications for funding, access and models of care require further exploration that is beyond the scope of this article. But consider, for example, the three aforementioned aged care insufficiencies, repeated below, with possible actions:

- RAC services tend to neglect the social and cultural needs of residents, often leaving them without access to activities that are meaningful to them.5 Iris Marion Young's Justice and the politics of difference11 suggests that addressing unmet social and cultural needs requires design, policy and practices that should at least not hinder, and ideally support, meaningful engagement with social group connections. RAC providers can consider how their homes empower freedom of association and residents’ expression of the customs and meanings of their affiliated groups.

- With minimal support from broader social networks, RAC residents are often left voiceless,5 leading to feelings of social isolation, disconnection and loneliness. Amitai Etzioni, in The spirit of community: rights, responsibilities and the communitarian agenda,17 proposes that healthy, supportive social communities should be built through fostering mutual responsibility and reciprocity. Social communities should seek to build such bonds with RAC homes, integrating them into, rather than segregating them from, the wider community. Policy makers should consider how policy and planning can foster connections between RAC and the wider social community to benefit residents and the wider community.

- Research conducted parallel to the Royal Commission argues that RAC homes have been predominantly designed without adequate consideration of the surrounding natural environment, leading to homes that hamper connection between residents and the natural world.6 In A Sand County almanac,12 Aldo Leopold argues that meaningfully recognising humans and their institutions as members of the ecological community encourages a shifted ethics, embedding consideration of ecosystem health and integrity within the ethical conscience. RAC homes should recognise their influential situation within the ecological community and understand that residents of the home are also connected to and flourish within that community. By embedding this consideration in decision‐making processes, providers and policy makers can consider how homes integrate with, and affect, nature. Making decisions that benefit the wider ecological community will positively affect residents and the wider social community.

If we continue with the existing transactional consumerism that limits the aged care sector to a framing of homes as providers delivering services to consuming residents, we cannot realise the paradigm shift demanded by the Royal Commission. Framing RAC as a community within communities based on a relational conception of the person would be a philosophical shift for the sector. Policy makers and providers should seek to embed an understanding of aged care as a social institution that constitutes, and is constituted by, social and ecological communities. With this underlying philosophy, theories of social and environmental justice can be applied to guide the development of the sector and the continued realisation of relational personhood and core aspects of wellbeing for residents.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Australian Catholic University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Australian Catholic University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Bridget Pratt and David Kirchhoffer are affiliated with the Queensland Bioethics Centre, which receives funding from the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Brisbane, the Catholic Bishops of Queensland, Mater Misericordiae Limited, Saint Vincent's Health Australia and Southern Cross Care Queensland. Authors’ views are their own.