On 11 March 2020, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization.1 Enormous strain was placed on hospital and health care systems around the world as patient numbers increased beyond the capacity of health care facilities to deal with them.1 The unpredictability and high transmissibility of the virus, combined with significant morbidity and mortality rates, prompted the Australian Government Department of Health to request that hospitals prepare contingency plans.2

In response to calls to bolster workforce capacity, Western Health in Victoria designed the Clinical Assistant (CA) program. The program recruited final year medical students on a voluntary basis to work as Level 4 Casual Support Service employees who, at 30 June 2023, were remunerated at $32.73 per hour. The role involved assisting with administrative and low risk clinical tasks around the hospital and was in addition to their medical school placements, many of which had been disrupted by COVID‐19 restrictions. CAs chose their area of work via self‐allocation to available shifts; they could opt to work within a single department or rotate across multiple departments depending on shift availability. To protect their clinical teaching time, hours were capped at 20 per week and shift times were flexible with the option to work evenings, weekends and holidays. CAs were directly supervised by the medical and nursing staff of the teams within which they worked, and tasks were aligned with Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand core competencies for final year medical students3 to ensure CAs worked within their scope of practice (Box 1). Since being pioneered at Western Health, similar models have been adopted by many health services in Victoria and throughout Australia, such as the Assistant in Medicine role in New South Wales;4 however, there is otherwise limited literature in the Australian context.

The concept of a pre‐internship is not a new one, and has been a part of the New Zealand medical curriculum since 1972.5 The year‐long paid pre‐internship was designed to increase medical students’ clinical experience and to help them balance education with service delivery.5 At the end of the pre‐internship year, 92% of New Zealand medical students felt prepared to become a junior doctor.5 Evans and colleagues6 found that an extended clinical induction program objectively enhanced preparedness for the role of a junior doctor in most clinical areas. The CA role is distinct from the pre‐internship program given the role is not part of the medical curriculum, rather an addition to it. However, the findings from the pre‐internship program suggest that a similar concept, such as the CA program, could enhance medical student preparedness in the Australian context.

The CA program continues to run in Victoria despite a decline in COVID‐19 cases, but it has shifted from supporting an acutely pressured workforce during a pandemic to supplementing a chronically strained workforce. As we move away from the shock of the pandemic, we recognise that workforce shortages, and therefore our response to them, are not specific to the COVID‐19‐context, nor to managing acute health conditions. Workforce shortages have plagued the Australian health care system for decades,7 leading to poor access and inequity for a significant proportion of the population. The problem will worsen in the face of an ageing population, increasing life expectancy, and declining fertility rates.8 Health workforce analysis suggests that traditional health care models will not cope with the increasing demand and that workforce restructure must be an essential component in addressing this crisis.9

This article explores the benefits of the CA program from a range of stakeholder perspectives and proposes mechanisms to ensure its sustainability in a non‐COVID‐19 context. We consider the suitability of the model in addressing ongoing workforce shortages in the medical field and recognise the potential for the model to be applied across multiple health contexts, and indeed in other industries facing similar challenges.

Stakeholder benefits

Feedback on the CA program has been extremely positive. An internal evaluation conducted in 2020 found that among Heads of Units and other supervisors of CAs, 82% found them to be extremely useful, particularly with regard to decreasing the workload of junior doctors (internal report, Western Health). While CAs attend to administrative and simple clinical tasks, doctors can concentrate their time and energy on important tasks such as prescribing medication and treating patients.

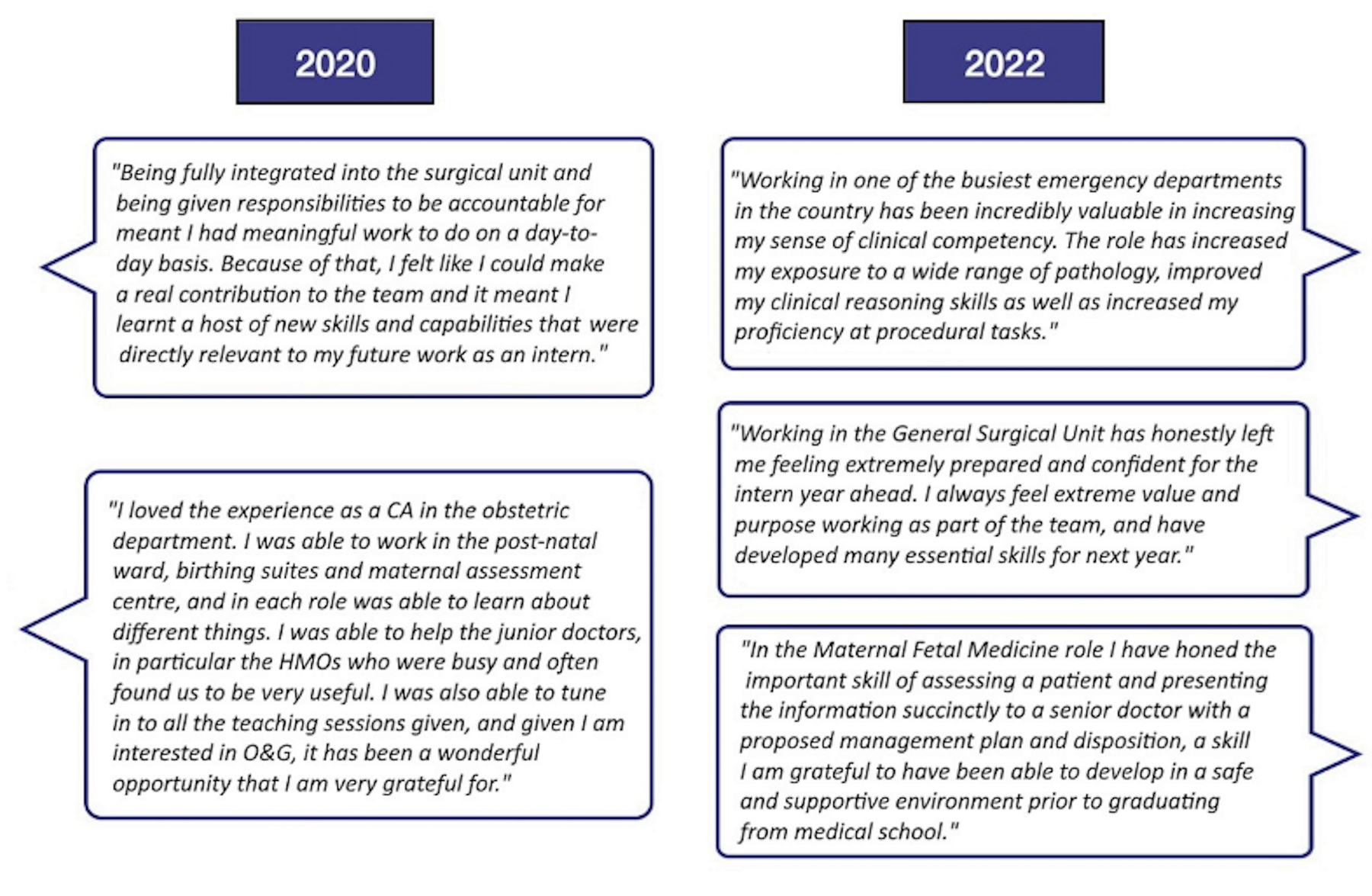

CAs themselves experienced immense benefits from participating in the program, owing to the increased clinical responsibility, autonomy, and level of inclusion, compared with their roles as medical students (internal report, Western Health). The benefit to medical students was essential given the repeatedly cancelled clinical‐based learning opportunities and overall negative experience during the pandemic. Among CAs, 87% found the program extremely useful and meaningful, and 96% stated it would be a very or extremely useful experience for any medical student (internal report, Western Health). This is supported by Dornan and colleagues,10 who found that medical students gain confidence and a medical identity when they are able develop clinical skills and interact with the treating team, and Idil and colleagues,11 who found that CAs in the United Kingdom gained a significant improvement in confidence regarding procedural and ward‐based tasks. As the Western Health CA program extends beyond COVID‐19‐specific roles, students report continuing benefits (Box 2), as the program can support their development as future doctors in a contemporary health system.

In addition to benefits reported by staff and CAs, benefits to other stakeholders may include enhancement of service delivery, better continuity of care and experience for patients, and increased economic efficiency. The overall benefits (Box 3) highlight the potential usefulness of the CA program beyond a short term pandemic workforce.

Sustainable solutions

As the CA role continues to expand to meet the needs of the health care system, there is a need for clear guidelines to ensure clarity of role expectations to allow transferability of the program across different jurisdictions and disciplines. CAs often work within departments that host medical student placements. This creates the potential for role confusion, as has been found with nursing students who concurrently work as health care assistants.12 Government guidelines for use of medical CAs in the emergency department2 provide a broad overview of the expectations of a CA and could be expanded as a guideline for CAs in other health care settings. To further embed the CA program into the hospital workforce structure, the program's employment conditions should be governed by a single enterprise agreement, similar to the nursing or midwifery student employment model.13 Given the current workforce shortages7 and predicted required increase in skilled health care and social assistance professionals of 301 000 by 2026,14 CAs have the potential to be an ongoing and sustainable workforce for an understaffed health care system. Care must be taken to ensure they are protected from pressures to work outside their scope of practice, or to prioritise CA work over medical school commitments.

Health care and beyond

The translational nature of the CA model has already been demonstrated through the variety of roles that CAs have undertaken within Western Health (Box 1). However, the long term possibilities of a readily available and flexible workforce are yet to be fully realised. CAs, unlike junior doctors, are not bound by rotations of specific length, assessment hurdles, or a specific training structure; they form a dynamic workforce that is available and adaptable to meet the health care system's specific needs at any given time. As we emerge from the pandemic, medical students could be one sustainable solution to chronic staffing shortages and to provide the health care workforce contingencies.

CAs could also play a key role in other segments of the health system. CAs could act as navigators to older patients and patients with chronic diseases as they transition from the hospital environment to their usual residence — a high risk transition point in upholding patients’ goals of care and avoiding unnecessary hospital visits. CAs could also bolster the medical presence in the community and aged care settings, both of which are desperately needed alongside our allied health and nursing colleagues. CAs could also play a key role in primary care, mental health, and potentially as concierges helping vulnerable patients to access and navigate the health system in times of need.

In addition to its potential in a non‐pandemic environment, the CA model could also be applicable outside of medicine. The health care sector is not the only industry to have suffered from the pandemic, nor the only one to have utilised students to bolster workforce capacity. Disrupted classroom education led the Victorian government to invest in the Tutor Learning Initiative, a program which allows pre‐service (student) teachers to be employed as education support class employees.15 Like the CA program, pre‐service teachers work under the supervision of a registered teacher in their area of training.

The parallels between these programs highlight the utility of a flexible, student‐based labour pool in addressing workforce gaps. Other industries should consider a pilot implementation of this model as a sustainable solution to labour shortages. Looking forward, a formal evaluation should be conducted on the CA program to objectively measure its success and sustainability into the future, given the wide‐ranging and positive outcomes this model could bring to many facets of our community.

Box 1 – Clinical Assistant (CA) roles at Western Health, Victoria: departments and responsibilities

|

CA roles |

Department |

Responsibilities |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COVID‐19‐specific |

Emergency Department, Respiratory Assessment Clinic |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Dialysis Unit |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Western Public Health Unit |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Maternal Fetal Medicine COVID‐19 Outreach |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Non‐COVID‐19‐specific |

Emergency Department |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

General Surgery |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

Urology |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

EMR Super User |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COVID‐19 = coronavirus disease 2019; EMR = electronic medical record; PCR = polymerase chain reaction. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Remarks from Clinical Assistants about their experience with the program, 2020 and 2022 (internal evaluation reports, Western Health)

Box 3 – Potential stakeholder benefits

|

Stakeholders |

Potential benefits |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Clinical Assistants |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Clinical teams |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Health care system/hospitals |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Patients/community |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID‐19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed 2020; 91: 157‐160.

- 2. Department of Health and Aged Care. Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID‐19). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/02/australian‐health‐sector‐emergency‐response‐plan‐for‐novel‐coronavirus‐covid‐19_2.pdf (viewed Dec 2023).

- 3. Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand. Guidance statement: Clinical practice core competencies for graduating medical students. May 2020. https://medicaldeans.org.au/md/2023/06/mdanz_2020_may_core_competencies.pdf (viewed Oct 2023).

- 4. Monrouxe LV, Hockey P, Khanna P, et al. Senior medical students as assistants in medicine in COVID‐19 crisis: a realist evaluation protocol. BMJ Open 2021; 11: e045822.

- 5. Dare A, Fancourt N, Robinson E, et al. Training the intern: the value of a pre‐intern year in preparing students for practice. Med Teach 2009; 31: e345‐e350.

- 6. Evans DE, Wood DF, Roberts CM. The effect of an extended hospital induction on perceived confidence and assessed clinical skills of newly qualified pre‐registration house officers. Med Educ 2004; 38: 998‐1001.

- 7. Productivity Commission. Australia's health workforce: Productivity Commission research report. 22 Dec 2005. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/health‐workforce/report/healthworkforce.pdf (viewed June 2022].

- 8. Segal L, Bolton T. Issues facing the future health care workforce: the importance of demand modelling. Aust N Z Health Policy 2009; 6: 12.

- 9. Harrington M, Jolly R. The crisis in the caring workforce. Canberra: Parliament of Australia, 2013. https://www.Aph.Gov.Au/about_parliament/parliamentary_departments/parliamentary_library/pubs/briefingbook44p/caringworkforce (viewed June 2022).

- 10. Dornan T, Boshuizen H, King N, et al. Experience‐based learning: a model linking the processes and outcomes of medical students’ workplace learning. Med Educ 2007; 41: 84‐91.

- 11. Idil M, Brown N, Rogers M, et al. A review of the clinical assistant workforce during COVID‐19 at a district general hospital. Future Healthc J 2021; 8 (Suppl 1): 26‐27.

- 12. Hasson F, McKenna HP, Keeney S. A qualitative study exploring the impact of student nurses working part time as a health care assistant. Nurse Educ Today 2013; 33: 873‐879.

- 13. Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation Victorian Branch. Nurses and midwives (Victorian public sector) (single interest employers) enterprise agreement 2020‐2024. https://www.anmfvic.asn.au/~/media/files/anmf/eba%202020/campaign%20updates/200120‐NandM‐EBA‐master‐clean.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 14. National Skills Commission. Projecting employment to 2026. Mar 2022. https://www.jobsandskills.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022‐03/NSC22‐0041_Employ%20Projections_glossy_FA_ACC.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 15. Victorian Department of Education. Tutor Learning Initiative. https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/tutor‐learning‐initiative/policy (viewed June 2022).

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Victoria University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Victoria University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

No relevant disclosures.