Evidence showing the importance of education as a determinant of individuals’ health and wellbeing is among the most agreed by scholars and practitioners.1 Quality and equity of education have strong associations with individuals’ life expectancy, morbidity and health behaviour, and educational attainment is important to people's health as it shapes their further education, employment and success in life.2

Therefore, high quality education and health for all children and young people is at the heart of employment pathways for societal progress that reaps profound intergenerational benefits. It is one of seven domains considered in the MJA supplement on the Future Healthy Countdown 2030. Australia is struggling to provide the foundations for learning and wellbeing for many young Australians that would enable them to live a good life in adulthood. We can turn this around by broadening the approaches to and outcomes of schooling from academic grades to whole child development, including better wellbeing and health for all.

Much effort, little progress

In international light, Australia has an advanced education system. In many ways it offers world‐class learning opportunities to children and youth, but unfortunately not for everyone. While having mostly well educated teachers and many innovative schools, Australian education is rated as unequal when compared with education systems of other advanced wealthy nations.3 This is not a problem caused by schools or teachers; it is because the education system has been designed in a way that leaves many children behind in both learning and health outcomes.4,5 But it does not have to be this way.

Education and health in modern societies are not cheap — anywhere. On average, Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) countries invested about 3.5% of their national wealth (or gross domestic product [GDP]) in primary and secondary education and 9.7% in health in 2020.6,7 Australia spends more than other OECD countries on school education — 4.1% of GDP. Where that money to finance schools comes from varies from country to country. In European Union countries and the United States, for example, private share of total education expenditure is about 8%, while in Australia it is 18%.8 Another way to say this is that Australian governments spend about the same amount of GDP on school education as OECD countries on average, and that the rest comes from parents and other private sources. So, most Australian parents who can afford to pay have access to world‐class schooling for their children.

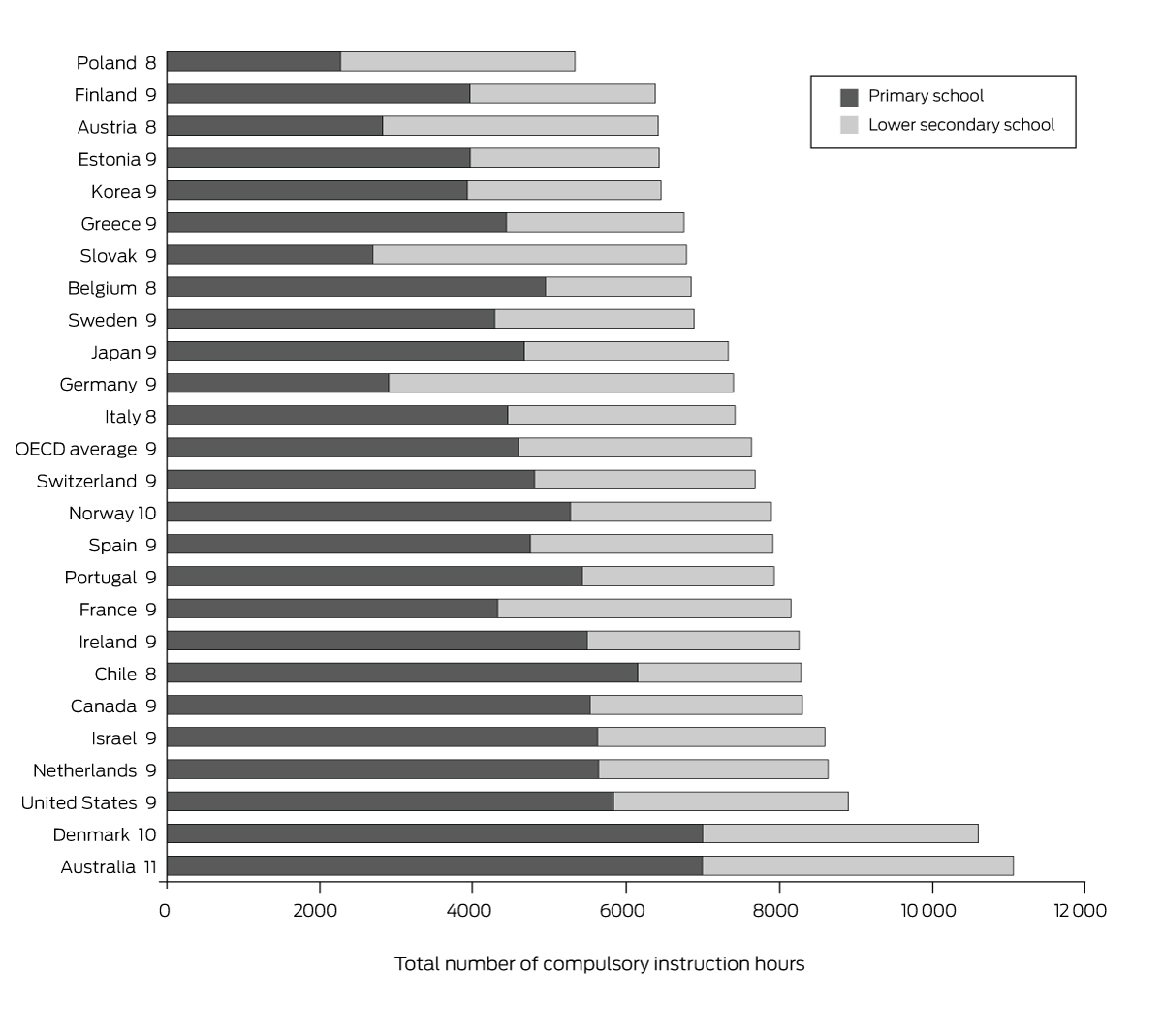

Another difference between Australian schools and those of the OECD countries is that Australian children spend more time in school receiving compulsory instruction than their peers in other OECD countries.8 In OECD countries, on average, students have 4600 hours of primary education and 3000 hours of lower secondary education. Australian children have about 11 000 hours of primary and lower secondary education in total, as shown in Box 1. This is considerably more than in OECD countries on average, and yet these long hours of formal instruction do not turn into high quality learning outcomes or positive wellbeing as measured by current student assessments and health surveys.

Another peculiar feature of Australian education today is persistent reliance on parental choice in the education marketplace as the preferred way to maintain and enhance learning outcomes for all. Free and only loosely managed school choice has been a defining part of federal and state public policies in the past, even when international advice has warned about adverse consequences of market models in education.9,10 As increasing amounts of government funds have been channelled into private and religious schools, chronic underfunding of most public schools has exacerbated inequities and contributed to higher concentration of disadvantaged students in the public system and declining equity of outcomes in Australia. The problem of socio‐educational segregation in Australia is widespread — more than 12% of all students are enrolled in a school where most children are socio‐educationally disadvantaged, and almost all students who are in schools with high concentrations of socio‐educational disadvantage are in public schools.11

It is not surprising that student learning and wellbeing does not flourish in this unequal and unfair educational environment. More data are being collected from schools and more money is being spent on schools than ever before, but educational performance (in terms of quality and equity) has not improved.12 This suggests that there is a need for different thinking about policies and strategies that would change these inconvenient trends for the better. The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration provides a useful framework for doing so.13

Snapshots of current student learning trends

Pressing educational issues for Australian children and young people are well researched and reported.14,15,16 The challenge is more about how all that knowledge and understanding could be turned into better operational policies and investments that would make a positive difference. Moreover, trends in student learning and prevalent achievement gaps between various equity groups are nothing new (Box 2, Box 3); policy makers have been aware of these issues for a decade or more.

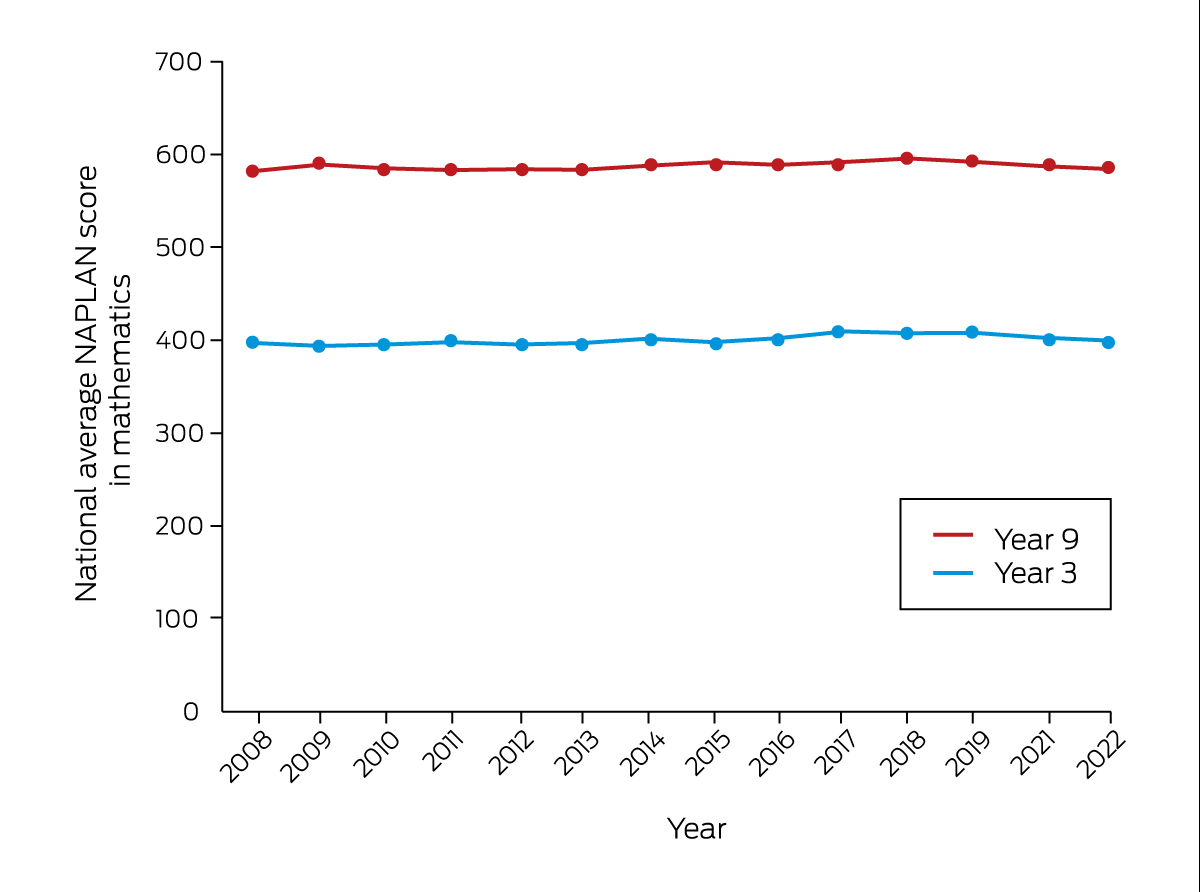

Data from the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) that have been collected across the nation since the year 2008 provide another window to understanding educational progress, or lack of it, in Australian states and territories. NAPLAN tests students’ knowledge in reading and mathematics in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9. Overall, there has been no progress in literacy and numeracy since 2008, although the reason for introducing NAPLAN was to improve educational performance across the nation. For example, Australian students’ achievements in mathematics as measured by NAPLAN in Year 3 and Year 9 have not improved since 2008 (Box 2).

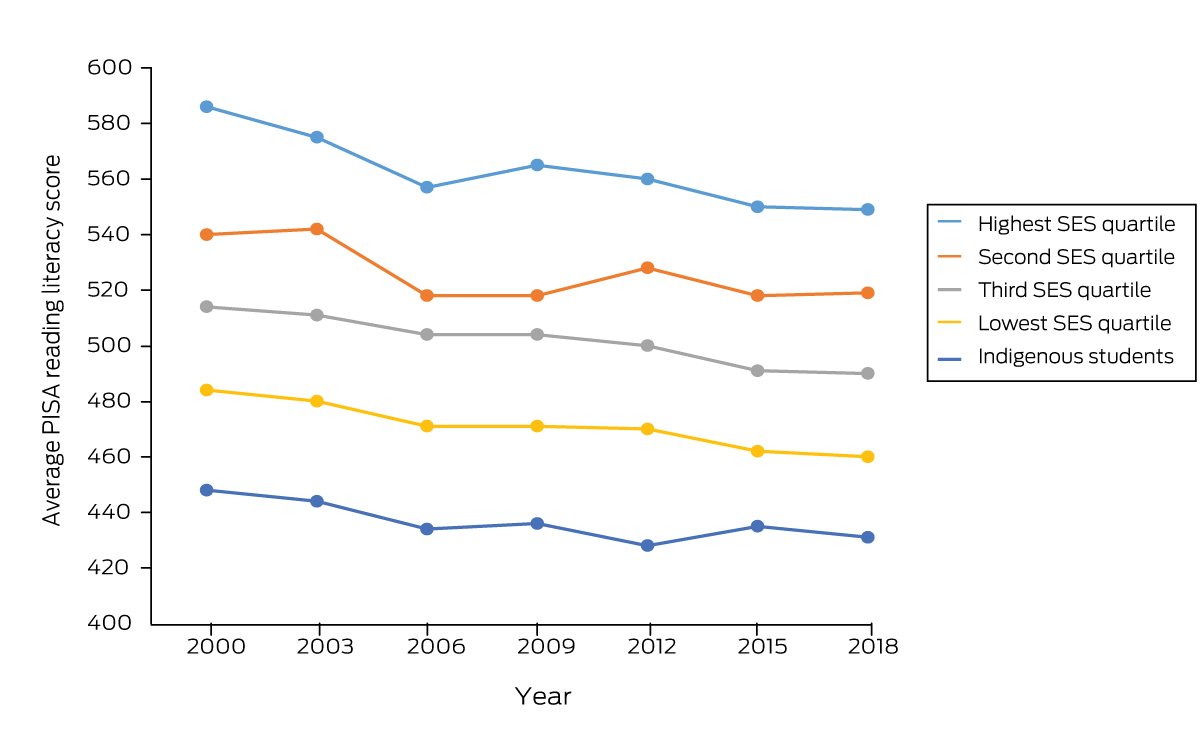

It has been frustrating that despite numerous reforms, reviews and growing financial spending, Australian students’ performance in basic school subjects has not improved during the past two decades. Educational performance in Australia as a whole and within its different jurisdictions has systematically been measured since the 2000s. The OECD Programme for International Student Assessment surveys show that, in comparison to international benchmarks, Australian students’ academic achievements have declined since 2000.17 These data also show that large achievement gaps between different socio‐economic and other equity groups have persisted since 2000 (Box 3).

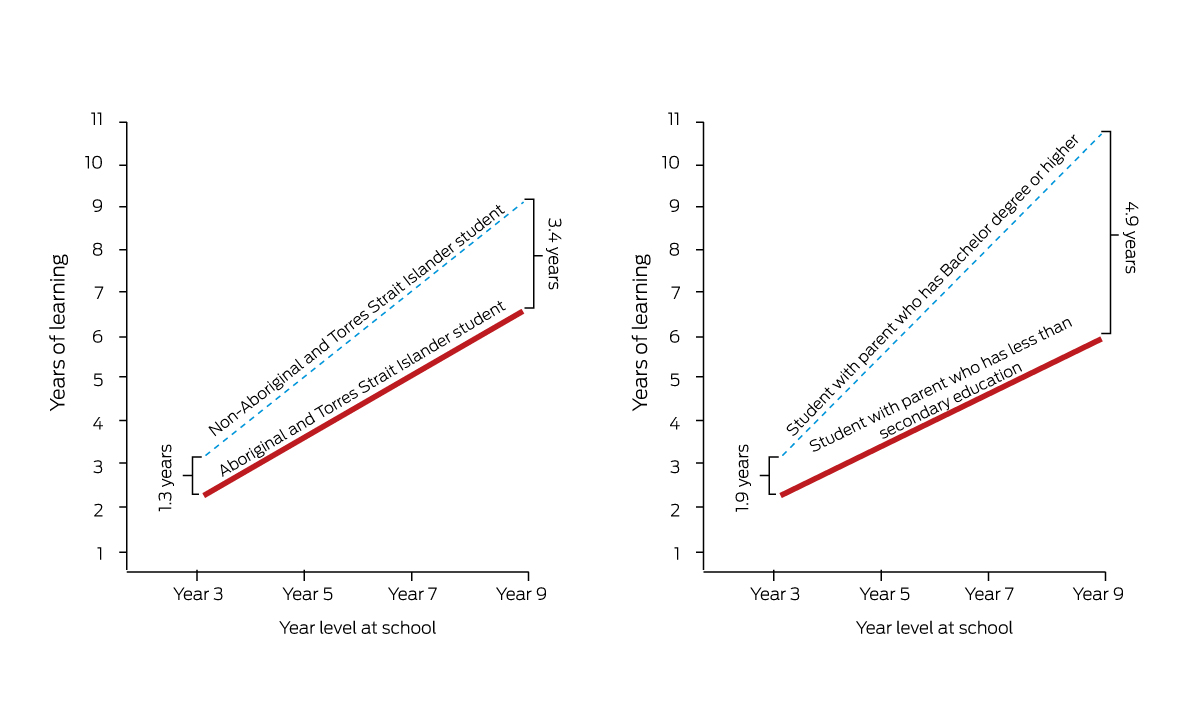

There are notable differences in average student outcomes between different schools in Australia, beyond what could be explained by students’ backgrounds. The Productivity Commission analysis of NAPLAN data collected between 2013 and 2021 for mathematics revealed that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students enrolled in schools with high concentrations of socio‐educational disadvantage (that are mostly government schools) were about half a year of learning behind other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students in Year 3.11 This learning gap grew to 1.3 years by Year 9.

Learning gaps between children from different equity groups that are substantial at the beginning of formal education are often magnified rather than narrowed during school years. This means that the time it would take for a typical student from a disadvantaged equity group to catch up with other students increases while students are in school. For example, learning gaps in mathematics continue to grow when the same cohort of students is followed from Year 3 to Year 9 (Box 4).

New foundations for learning

Not so long ago, for most children, school was the only place to learn sufficient basic knowledge and skills needed to have a job and live a good life. School then held the monopoly of learning. Now that monopoly is gone — children can learn anywhere, any time. Schools still play a significant role in teaching complex skills and competencies that are needed in work and the increasingly uncertain world. Critically, school should be the environment in which all children need to learn new skills for life and contemporary work, not just the basic knowledge and skills. School is also a place where they can develop attitudes and mindsets that equip them to participate confidently in a complex world. These new foundations — such as ability to think flexibly, manage impulsivity, use imagination in new situations, seek opportunities in complex situations, identify and use necessary resources, regulate one's own thinking, understand and improve one's own wellbeing, and take responsible risks — enable self‐regulated behaviour plus critical and creative thinking.18,19,20

As children and young people continue to learn through a variety of experiences in and out of school, it is becoming more important to address their personal interests and individual learning needs properly in school. Children's self‐directed, informal learning at home and in communities is taking an increasingly important role as digital technologies have become a natural way to communicate and process information. This was recently recognised by the Nest framework, developed by the Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth in 2021, in which a new generation of child and youth voices defined the learning and employment pathways they require. Their definition emphasised the importance of having opportunities to participate “in a breadth of experiences where their learning is valued and supported by their family and in the wider community”.21 Student agency, in appropriate ways, in building these new foundations is critically important.

Continuing to do more of the same to transform education makes no sense. We have all the necessary knowledge and practical wisdom to change the course towards a better and fairer education for all Australian children. But we need to do different things, and do them differently enough, to get there. For instance, improving education experiences for Indigenous children requires recognising the importance of First Nations’ knowledge and knowing, and this would benefit all children in Australia.

National education policies have recognised that schools need to educate students for a world yet to be realised, meeting the needs of all students, and equipping them with transversal skills and general capabilities for future work and lifelong learning. International evidence suggests that there should be multiple pathways from school to the world of work if we want to meet the needs and interests of all young people.22 Furthermore, as we have suggested elsewhere, new foundations for learning should be built on whole child and whole school approaches that establish closer connections between learning and wellbeing in schools.23

Education attainment is a strong predictor of steady employment and better physical and mental health.24 The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare has identified the need for reporting to link health and welfare data to better understand the effects of social determinants of health and wellbeing through life: “Across all key determinants, evaluation of programs and interventions to identify successes in reducing inequalities is important.”25 The evidence is clear that education and health are positively connected — healthier students are better learners — and vice versa.26,27,28

If we are to turn things around by 2030, indicators need to focus attention on the range of current inequities in education outcomes in Australian education.29 These indicators also need to report publicly on policy approaches to reducing these inequities and progress made in terms of learning a broader range future skills and competencies at federal, state and territory levels throughout schooling from early learning to higher education and beyond. The National Report on Schooling in Australia as an annual review should provide the benchmarks for policy targets and new outcomes that address and reduce inequities. Key indicators relating to equity of education that are available are:- proportion of students at or below proficiency levels in reading and mathematics;

- proportion of students enrolled in schools with high concentrations of socio‐educational disadvantage;

- achievement gaps in reading and mathematics between disadvantaged students in different equity groups in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9; and

- reading and mathematics achievement by the level of socio‐economic and educational disadvantage.

- clear and shared definition of what equity of education outcomes means across different education systems and sectors;

- data on broader outcomes of schooling (eg, transversal skills, psychosocial health and wellbeing, happiness, life satisfaction);

- student agency and engagement in school; and

- safety and belonging in school (for both children and adults).

The evidence (summarised in Box 5) is clear and the road ahead should be too — educational and health inequities need to be addressed now before it is too late.

Box 1 – Total number of compulsory instruction hours in OECD countries in primary and lower secondary education in 2019*

OECD = Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development.* Source: OECD Programme for International Student Assessment database. Number after country indicates duration of primary and lower secondary education in years.

Box 2 – Australian students’ national average achievements in mathematics in Year 3 and Year 9, 2008–2022*

NAPLAN = National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy.* Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority database.

Box 3 – Australian 15‐year‐old students’ average reading literacy scores in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), 2000–2018*

SES = socio‐economic status.* Source: OECD Programme for International Student Assessment database.

Box 4 – Australian students’ average mathematics scores in NAPLAN in the same cohort from 2015 to 2021*

NAPLAN = National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy.* Source: Productivity Commission estimates of de‐identified student‐level NAPLAN data.

Box 5 – New foundations for learning in Australia

What are the most pressing issues where change could make a real difference by 2030 and why?- Academic outcomes are stagnant or declining while per‐student spending is going up.

- Student engagement in school weakens during schooling and fewer students think they benefit from schooling.

- Equity of education outcomes is weak and has worsened over time.

- More and more data are being collected — using data for transforming schools has become a problem.

-

Key indicators

- ‣ regular census‐based data on literacy and numeracy proficiencies by year level (Years 3, 5, 7 and 9); and

- ‣ school completion rates for Year 12 (or equivalent).

-

What is lacking?

- ‣ data on broader skills and competencies learned across Australian curricula in school, including creative problem solving, complex communication, self‐regulation and lifelong learning; and

- ‣ better data on student agency and engagement, wellbeing, and sense of belonging in school.

- More than 20% of Australian 15‐year‐olds were low performing students in reading and mathematics in the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development's Programme for International Student Assessment survey conducted in 2018.

- More than 12% of Australian students are enrolled in a school with high concentrations of socio‐educational disadvantage and that trend is worsening over time according to the MySchool database.

- For reading, the measured achievement gap between socio‐educationally disadvantaged and advantaged students grows almost threefold from Year 3 to Year 9 according to the Australian Curriculum, Assessments and Reporting Authority (ACARA) database.

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Education: a neglected social determinant of health [editorial]. Lancet Public Health 2020; 5: e361.

- 2. Welsh J, Bishop K, Booth H, et al. Inequalities in life expectancy in Australia according to education level: a whole‐of‐population record linkage study. Int J Equity Health 2021; 20: 178.

- 3. UNICEF Office of Research. An unfair start: inequality in children's education in rich countries (Innocenti Report Card 15). Florence: UNICEF, 2018.

- 4. Greenwell T, Bonnor C. Waiting for Gonski. How Australia failed its schools. Sydney: UNSW Press, 2022.

- 5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's children (AIHW Cat. No. CWS 69). Canberra: AIHW, 2020.

- 6. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development. Education at a glance 2022. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2022.

- 7. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health expenditure. https://www.oecd.org/health/health‐expenditure.htm (viewed Aug 2023).

- 8. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development. Education at a glance 2021. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2021.

- 9. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development. Equity and quality in education: supporting disadvantaged students and schools. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2012.

- 10. Daley J. The myth of markets in school education. Melbourne: Grattan Institute, 2013. https://grattan.edu.au/report/the‐myth‐of‐markets‐in‐school‐education (viewed Aug 2023).

- 11. Productivity Commission. Review of the National School Reform Agreement: study report. Canberra: Productivity Commission, 2023. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/school‐agreement/report (viewed June 2023).

- 12. Productivity Commission. 5‐year Productivity Inquiry: From learning to growth. Inquiry report – volume 8. Canberra: Productivity Commission, 2023. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/productivity/report/productivity‐volume8‐education‐skills.pdf (viewed Oct 2023)

- 13. Council of Australian Governments Education Council. Alice Springs (Mparntwe) education declaration. Melbourne: Education Council, 2019.

- 14. Reid A. Changing Australian education. How policy is taking us backwards and what can be done about it. London: Routledge, 2019.

- 15. Savage G. The quest for revolution in Australian schooling policy. London: Routledge, 2021.

- 16. Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. NAPLAN. https://acara.edu.au/assessment/naplan (viewed Aug 2023).

- 17. Thomson S, De Bortoli L, Underwood C, Schmid M. PISA 2018: Reporting Australia's Results. Volume I: Student Performance. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research, 2019.

- 18. Costa AL, Kallick B. Dispositions. Reframing teaching and learning. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press, 2013.

- 19. Winkelman TN, Caldwell MT, Bertram B, Davis MM. Promoting health literacy for children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2016; 138: e20161937.

- 20. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development. The future of education and skills. Education 2030. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030‐project/contact/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf (viewed Aug 2023).

- 21. Goodhue R, Dakin P, Noble K. What's in the Nest? Exploring Australia's wellbeing framework for children and young people. Canberra: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth, 2021. https://www.aracy.org.au/documents/item/700 (viewed Oct 2023).

- 22. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development. Pathways to professions. Understanding higher vocational and professional tertiary education systems [policy brief]. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2022. https://www.oecd.org/skills/centre‐for‐skills/Pathways‐to‐Professions‐Policy‐Brief%20.pdf (viewed June 2023)

- 23. Sahlberg P, Goldfeld S, Quach J, et al. Reinventing Australian schools for the better wellbeing, health and learning for every child. University of Melbourne, Murdoch Children's Research Institute and Southern Cross University, 2023. https://www.rch.org.au/uploadedFiles/Main/Content/ccchdev/2305_Reinventing‐schools_Discussion‐Paper.pdf (viewed May 2023).

- 24. Sahlberg P, Cobbold T. Leadership for equity and adequacy in education. Sch Leadersh Manag 2021; 41: 447‐469.

- 25. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 4.1 Social determinants of health. In: Australia's health 2016 (AIHW Cat. No. AUS 199; Australia's Health Series No. 15). Canberra: AIHW, 2016.

- 26. Michael SL, Merlo CL, Basch CE, et al. Critical connections: health and academics. J Sch Health 2015; 85: 740‐758.

- 27. Basch CE. Healthier students are better learners: a missing link in school reforms to close the achievement gap. J Sch Health 2011; 81: 593‐598.

- 28. Zimmerman E, Woolf SH. Understanding the relationship between education and health. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine, 2014.

- 29. Darling‐Hammond L, Flook L, Schachner A, Wojcikiewicz S (in collaboration with Cantor P and Osher D). Educator learning to enact the science of learning and development. Palo Alto: Learning Policy Institute, 2022.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Melbourne, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Melbourne agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

This article is part of the MJA supplement on the Future Healthy Countdown 2030, which was funded by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) — a pioneer in health promotion that was established by the Parliament of Victoria as part of the Tobacco Act 1987, and an organisation that is primarily focused on promoting good health and preventing chronic disease for all. VicHealth has played a convening role in scoping and commissioning the articles contained in the supplement.

No relevant disclosures.