Diabetes‐related foot disease (DFD) — foot ulcers, infection and ischaemia — is a leading cause of hospitalisation, amputation, disability, and health care costs.1,2,3,4,5,6 In Australia each year, DFD affects around 50 000 people, causing 28 000 hospitalisations, 5000 amputations and $1.6 billion in costs.1,2,3,4,5 Further, 300 000 Australians are at risk of DFD, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples have up to a 38‐fold risk of developing DFD and ensuing amputations.1,2,3,4,7

Despite the large national DFD burden, Australian regions implementing guideline‐based care have demonstrated large reductions in their regional DFD burdens and costs.4,8,9,10,11 However, the most recent Australian guideline on DFD was published in 2011,12 many of its recommendations are now outdated,1,13 and the body of research on DFD has since expanded considerably.14 Therefore, the recent Australian DFD Strategy recommended an urgent update of Australian DFD guideline to inform contemporary evidence‐based practice and help reduce the large burden of DFD.1,2

To address this gap, Diabetes Feet Australia (DFA; a division of the Australian Diabetes Society) recently developed and published a suite of six new guidelines that make up the new Australian evidence‐based guidelines for the prevention and management of DFD. The six full guidelines are available at https://jfootankleres.biomedcentral.com/.15,16,17,18,19,20,21

Methods

The methodology for developing these guidelines is detailed in a published protocol.15 In brief, as the funding necessary to develop guidelines de novo was unavailable, DFA appointed a guidelines development group comprising multidisciplinary clinical, research, guideline, consumer and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander experts in DFD to adapt suitable international guidelines to the Australian context.15 Experts were defined as having nationally or internationally recognised track records in DFD research, guideline development, or lived experience. This group developed the protocol following eight key steps adhering to the ADAPTE and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approaches as recommended by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines for adopting or adapting international guidelines.22,23,24

First, the scope was defined to develop new evidence‐based guidelines that informed the practice of the multidisciplinary health professionals that provide prevention or management for populations with or at risk of DFD in the Australian context. DFD was defined as infection, ulceration, or tissue destruction of the foot in a person with diabetes.25,26 Second, a systemic search was undertaken to identify all international DFD guidelines in international and Australian guideline registers by three independent authors (PAL, AR and JP). Third, all international guidelines identified were assessed independently by four authors (PAL, AR, JP and RJC) for quality using a 23‐item Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument, plus suitability and currency using a 22‐item instrument customised from the NHMRC table of factors to consider when adapting guidelines.15,22,27 The suite of six International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) guidelines,28,29,30,31,32,33,34 along with their accompanying systematic reviews of all relevant studies in the field,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44 were identified as the only international DFD guidelines with appropriate quality, suitability and currency to adapt.

Fourth, all 100 recommendations (and associated rationale) in the IWGDF guidelines were systematically evaluated.28,29,30,31,32,33,34 This was undertaken by six panels each comprising six to eight nationally and internationally recognised experts in the DFD fields of prevention, classification, peripheral artery disease (PAD), infection, offloading, and wound healing interventions.15 Collectively, the panels comprised 30 experts from endocrinology, infectious diseases, vascular surgery, orthopaedic surgery, wound care nursing, podiatry, pedorthics, consumers, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Each panel rated all recommendations in their field for acceptability and applicability in the Australian context using a seven‐item ADAPTE form by consensus.24 Where panels rated all seven items as acceptable or applicable, the recommendation was adopted. Where panels rated any item as unsure or not acceptable or applicable, the panel performed a full re‐evaluation of the recommendation using the GRADE Evidence to Decision framework to facilitate judgements on eight important criteria: the problem, desirable effects, undesirable effects, quality of evidence, values, balance of effects, acceptability, and feasibility.15,23 A decision was made to adopt, if all panel and IWGDF criteria judgements were in agreement; adapt, if some disagreements; or exclude, if substantial disagreements.15

Fifth, panels redrafted recommendations (and rationale) using the GRADE approach.15,23 For adopted recommendations, the wording, strength of recommendation and quality of evidence remained the same. For adapted recommendations, the wording was redrafted to be clear, specific and unambiguous on what was recommended.15,23 The strength of recommendation was re‐evaluated as “strong” or “weak”, based on the extent to which the panel was confident that the desirable effects (benefits) of the intervention clearly outweighed the undesirable effects (harms), based on the available evidence, applicability and feasibility in the Australian context.15,23 A strong recommendation implies the desirable effects of the intervention clearly outweigh the undesirable effects, and most people in this situation would be best served using this recommendation.15,23 A weak recommendation implies the desirable effects probably outweigh the undesirable effects, but there is a need to carefully consider each person's situation before using.15,23 Quality of evidence was re‐evaluated as high, moderate, low or very low, based on the extent the panel could be certain that the true effect was close to the effect estimates found for the critical outcomes in the available evidence supporting the recommendation and further research was unlikely to change their certainty.15,23 For excluded recommendations, the panel stated the recommendation was excluded. The panel then drafted rationale for all decisions, plus considerations on implementing the recommendation in Australia (including specifically for geographically remote and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples), monitoring and future research priorities.15,23

Sixth, panels drafted and incorporated all recommendations and rationale in a full guideline consultation manuscript. Seventh, each panel sought four to six weeks of public consultation on their consultation manuscript, collated feedback, transparently revised and sought endorsement from national peak bodies.15 Finally, panels incorporated all recommendations into pathways to aid implementation into practice,15 with pathways further developed into interactive online decision‐assisting pathways and a practical toolkit, available in full at https://www.diabetesfeetaustralia.org/new‐guidelines/.

Recommendations

Here we summarise the key recommendations considered most relevant for the general medical audience, with a focus on prevention and classification.16,17,18,19,20,21,45 In doing so, we highlight that many PAD, infection, offloading and wound healing management recommendations that are considered most relevant for specialist medical audiences have been omitted.16,17,18,19,20,21 Thus, we strongly suggest people with DFD are referred to interdisciplinary High Risk Foot Services or equivalent for management where possible.16,17,18,19,20,21

We also tabulated recommendations that are new or changed from the previous 2011 guideline along with their GRADE strength of recommendation and quality of evidence (Box 1, Box 2, Box 3, Box 4, Box 5 and Box 6). We further edited the tabulated recommendations for brevity and flow, and we refer the reader to the full guidelines for complete details on each recommendation, including rationale, implementation, monitoring, and research considerations.16,17,18,19,20,21 Otherwise, we highlight that most recommendations for DFD apply to healing or non‐healing DFD; we denote recommendations specifically for non‐healing DFD in Box 3, Box 4, Box 5 and Box 6.26

The most obvious change in the new guidelines is that they contain 98 recommendations across six DFD fields, whereas the previous guideline contained 25 recommendations across four DFD fields. The new guidelines also used the recommended GRADE methodological approach, whereas the previous used the historical NHMRC approach. Finally, these new guidelines have been endorsed by ten national peak bodies, including the Australian Diabetes Society, the Australian and New Zealand Society for Vascular Surgery, the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases, the Australian Podiatry Association, and Wounds Australia.16,17,18,19,20,21,45

Prevention

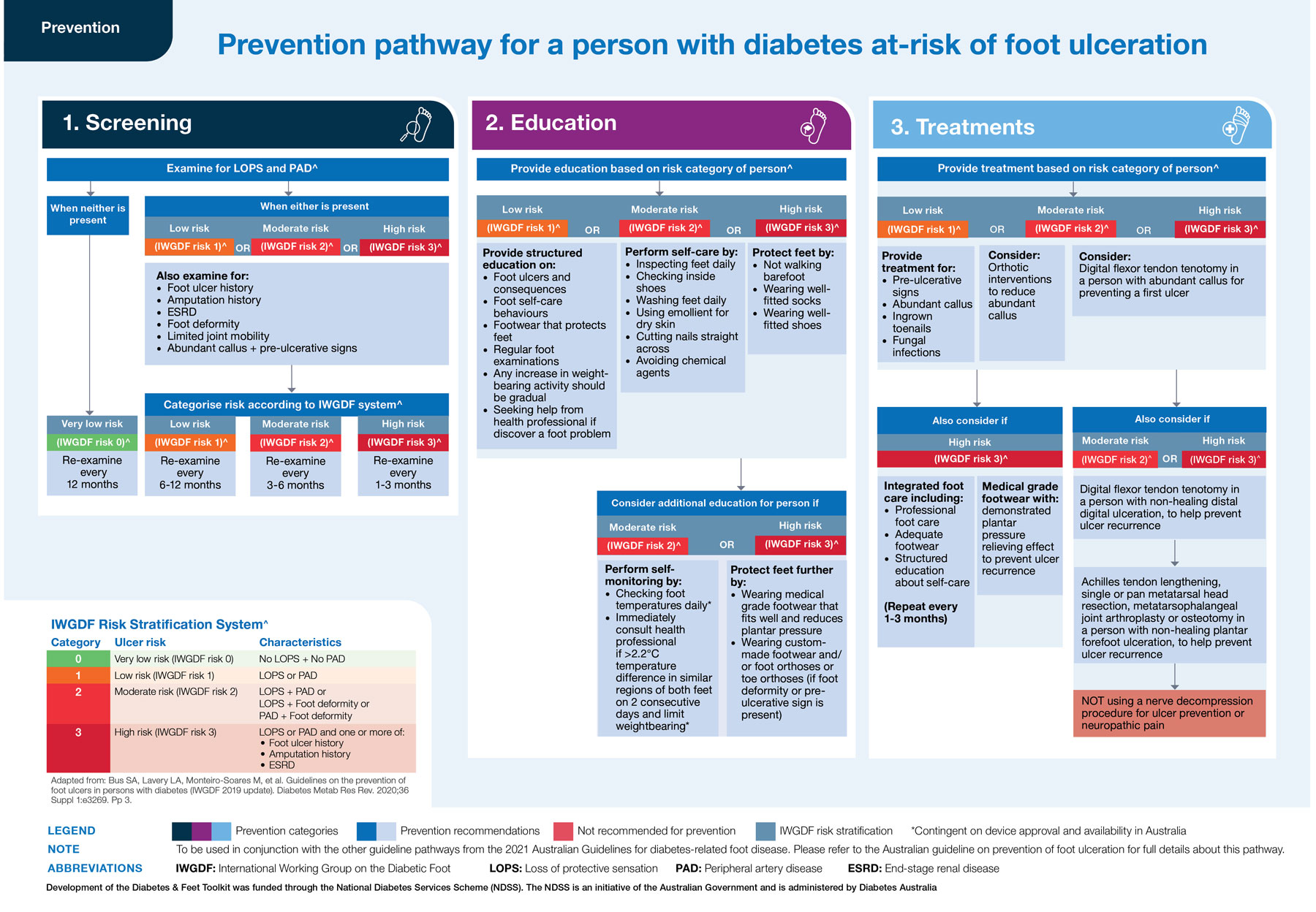

There are 15 prevention recommendations covering screening, education, self‐care, footwear and treatments for people at risk of DFD (Box 1 and Box 7).16 It is recommended that people with diabetes are screened at least annually for loss of protective sensation (LOPS) and PAD to determine any increased risk of diabetes‐related foot ulcers (DFU). For LOPS, this can be performed using a 10 g Semmes–Weinstein monofilament or Ipswich Touch Test; and for PAD, by taking a relevant history and palpating foot pulses.16,18 People identified to not have LOPS or PAD can be categorised at very low risk of DFU and rescreened in 12 months. Individuals identified to have LOPS or PAD should be further examined according to the IWGDF risk stratification system for foot deformities, abundant callus, pre‐ulcerative lesions, DFU history, amputation history, end‐stage renal disease, and DFU (Box 7). This examination categorises if the person is at low risk (and re‐examined every six to 12 months), moderate risk (re‐examined every three to six months), or high risk of DFU (re‐examined every one to three months) according to the IWGDF risk stratification system.16 For people with DFU, see the Classification section.17 These categories are based on systematic reviews finding increasing combinations of these risk factors (and risk categories) correspond with increasing likelihood of developing DFU.42,43 We note the IWGDF system is a change to the system in the previous guideline,12 as it includes end‐stage renal disease as an additional risk factor found to predict DFU development, and four risk categories with different combinations of risk factors instead of three in the previous guideline.16 The IWGDF risk stratification system should be considered the minimum standard to document and communicate risk of DFU with other health professionals (Box 7).16

For individuals identified at risk (low, moderate or high), education is recommended on DFU risk, foot self‐care (including daily inspection for foot problems), foot protection (including wearing well fitting footwear), regular foot examinations (as per above re‐examination recommendations), and how to seek care if a DFU is identified. In people looking to increase activity, a gradual increase in weight‐bearing activity while wearing appropriate well fitted footwear and daily inspection for foot problems is recommended. Further, treatment is recommended for any pre‐ulcerative lesions, callus, ingrown toenails and fungal infections, and prescription of orthotic interventions considered to reduce abundant callus.16

For people at moderate or high risk, prescribing medical‐grade footwear and instructing patients to self‐monitor foot skin temperatures daily to detect signs of pre‐ulcerative lesions (when systems become available in Australia) are also recommended. Further, for individuals at high risk, it is strongly recommended that medical‐grade footwear with demonstrated plantar pressure‐relieving effects be prescribed. Otherwise, if the above recommended non‐surgical treatment fails to reduce ongoing abundant callus or recurrent DFU, the use of various surgical interventions for the prevention of DFU should be considered.16

Classification

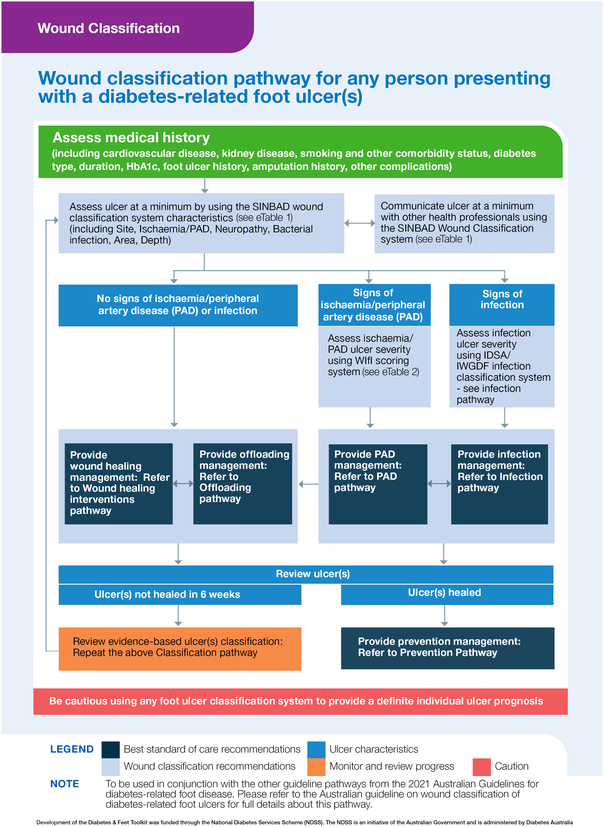

There are five classification recommendations covering ulcer, infection, ischaemia and auditing (Box 2 and Box 8).17 The Site, Ischaemia, Neuropathy, Bacterial Infection, Area and Depth (SINBAD) wound classification system is strongly recommended as the minimum standard to document and communicate DFU characteristics with other health professionals (Box 8 and Supporting Information, eTable 1).17 We note that SINBAD is a change to the previous guideline that recommended the University of Texas wound classification system,12 as SINBAD has demonstrated more effective communication between health professionals, does not require any specialised equipment, and has higher quality of evidence. Thus, there should be no barriers to using SINBAD in the primary care context, including when referring people with DFU to interdisciplinary High Risk Foot Services. Further, it is recommended that SINBAD also be used as a minimum for any service audits to allow comparisons between institutions on DFU outcomes.17

In people with infected DFU, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)/IWGDF infection classification system is recommended to classify severity and guide infection management (see Infection section).17,19 Additionally, in people with DFU who are being managed in settings with appropriate vascular expertise (such as interdisciplinary High Risk Foot Services), the Wound, Ischaemia and foot Infection (WIfI) classification system is recommended to aid decision making in the assessment of perfusion and likelihood of revascularisation benefit (see PAD section and Supporting Information, eTable 2).17,18

Otherwise, we highlight that classification using the above recommended systems is critical to achieving optimal outcomes for people with DFU, and important to facilitate effective communication among health professionals, referral, triage, and guide management decisions.17 Further, we point out that appropriate DFU classification is central to the below PAD, infection, offloading and wound healing management recommendations.18,19,20,21

Peripheral artery disease

There are 17 PAD recommendations covering diagnosis, severity classification, medical and surgical treatments for people with DFU (Box 3 and Supporting Information, eFigure 1).18 We note all are new, as no PAD recommendations were made in the previous guideline.12 In brief, it is recommended that all people with diabetes and DFU undergo at minimum a clinical examination for PAD, including relevant history and palpation of foot pulses.18 As clinical examination does not reliably exclude PAD, it is also strongly recommended that further non‐invasive bedside testing is performed, including pedal Doppler arterial waveforms, ankle systolic pressure, ankle brachial index (ABI) and/or toe systolic pressure. Vascular imaging and referral for possible revascularisation should always be considered for patients with a DFU and an ankle pressure below 50 mmHg, ABI below 0.5, or toe pressure below 30 mmHg. People with less severe ischaemia may also require revascularisation. Otherwise, it is strongly recommended that all centres treating DFU should have expertise in and/or rapid access to facilities necessary to diagnose and treat PAD.18

Infection

There are 35 infection recommendations covering diagnosis, severity classification, and medical and surgical treatments for people with DFU (Box 4 and Supporting Information, eFigures 2A and 2B).19 Again, we note all are new, as no infection recommendations were made in the previous guideline.12 In brief, it is recommended that foot infection is diagnosed clinically based on the presence of at least two signs and symptoms of local inflammation, including swelling/induration, erythema, tenderness/pain, warmth, or purulent discharge. If infection is diagnosed, it is strongly recommended that the IDSA/IWGDF classification system is used to classify severity as mild (involves only skin or subcutaneous tissue without erythema that extends > 2 cm around the DFU), moderate (involves deeper tissues and/or erythema that extends > 2 cm around the DFU) or severe (involves systemic manifestations of systemic inflammatory response syndrome). If osteomyelitis is suspected, a combination of the probe‐to‐bone test, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (or C‐reactive protein and/or procalcitonin) and plain x‐rays are recommended as the initial diagnostic studies. If the diagnosis remains in doubt, it is then recommended that advanced imaging studies be considered, such as magnetic resonance imaging scans. Diagnosis of foot infection severity informs the specific infection management recommendations (Box 4 and Supporting Information, eFigures 2A and 2B).19

Offloading

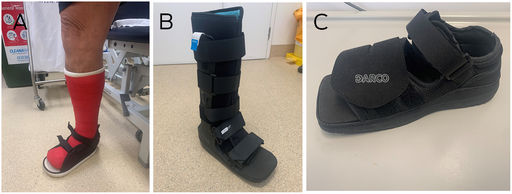

There are 13 recommendations covering offloading for different situations in people with DFU (Box 5, Box 9 and Supporting Information, eFigure 3).20 Offloading is defined as the relief of mechanical stress (pressure) from a specific area of the foot.20,31 We note nearly all recommendations are new, as only two offloading recommendations were made in the previous guideline.12 We also highlight that offloading management now has the strongest evidence to effectively heal DFU and should always be considered.15,46 In brief, for people with plantar DFU, it is strongly recommended that non‐removable knee‐high offloading devices (total contact cast or non‐removable knee‐high walker) should be provided as first line treatment unless contraindicated or not tolerated. If contraindicated (such as moderate infection) or not tolerated by the patient (such as unable to use for employment), then consider removable knee‐high offloading devices as second line treatment, removable ankle‐high offloading devices as third line, and medical‐grade footwear as last line. Otherwise, felted foam (or other pressure offloading insole) in combination with the chosen offloading device can be considered to further reduce plantar pressure. For people with non‐plantar DFU, depending on the DFU type and location, removable offloading devices, felted foam, toe spacers, or medical‐grade footwear are recommended. If non‐surgical offloading fails to heal a person with plantar DFU, various surgical offloading procedures should be considered, including Achilles tendon lengthening, gastrocnemius resections, metatarsal head resections, joint arthroplasty, or digital flexor tenotomies.20,38

Wound healing

There are 13 wound healing recommendations covering debridement, wound dressing selection, and other wound treatments in people with DFU (Box 6 and Supporting Information, eFigure 4).21 We note half of these recommendations are new compared with the previous guideline.12 The similar recommendations include:

- regular sharp debridement if not contraindicated;

- using wound dressings initially based on controlling exudate, comfort and cost;

- considering systemic hyperbaric oxygen therapy for ischaemic DFU; and

- considering negative pressure wound therapy for post‐surgical DFU.

The new recommendations for non‐healing DFU include considering the use of sucrose octasulfate‐impregnated dressings, placental‐derived products, or autologous combined leucocyte, platelet and fibrin dressings.21 However, we note these products have only been recently approved in Australia.21

Conclusion

For the first time in a decade, we have developed new Australian evidence‐based guidelines for DFD. These new guidelines have been endorsed by ten national peak bodies and we encourage all Australian medical professionals caring for people at risk of, or with DFD, to implement the recommendations contained in these new guidelines to help reduce the large patient and national burden of DFD in Australia.

Box 1 – Summary of key prevention recommendations

|

Recommendation |

GRADE |

||||||||||||||

|

Strength* |

Quality† |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Examine a person with diabetes at very low risk (IWGDF system) of foot ulceration annually for loss of protective sensation and PAD to determine if they are at risk of ulceration. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Screen a person determined at risk of ulceration (low to high risk) also for history of ulceration or amputation, end‐stage renal disease, foot deformity, limited joint mobility, abundant callus, and pre‐ulcerative signs on the foot. Repeat every 6–12 months for people at low risk, every 3–6 months for moderate risk, and every 1–3 months for high risk. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Consider instructing a person who is at moderate or high risk to self‐monitor foot skin temperatures once per day to identify any early signs of foot inflammation and help prevent an ulcer; contingent on systems approved in Australia. |

Weak |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

Instruct a person who is at moderate risk to wear medical‐grade footwear to reduce plantar pressure and help prevent ulcers. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Consider prescribing orthotic interventions, such as toe silicone or rigid or semi‐rigid orthotic devices, to help reduce abundant callus in a person at risk. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

In a person who has a healed plantar ulcer, prescribe medical‐grade footwear that has a demonstrated a plantar pressure‐relieving effect to help prevent recurrent ulcers. |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

Treat any pre‐ulcerative sign or abundant callus on the foot, ingrown toenail, and fungal infection to help prevent ulcers in a person at risk. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

In a person with abundant callus (and ulcer history), consider digital flexor tendon tenotomy for preventing ulcer recurrence. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

In a person with a plantar forefoot ulcer (history), consider Achilles tendon lengthening, single or pan‐metatarsal head resection, metatarsophalangeal joint arthroplasty or osteotomy to prevent ulcer recurrence. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Consider communicating to a person at risk that any increase in weight‐bearing activity should be gradual, ensuring appropriate footwear is worn and the skin is frequently monitored for pre‐ulcerative signs or injury. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

GRADE = Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; IWGDF = International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot; PAD = peripheral artery disease. * The GRADE strength of recommendation rating is defined as the extent the panel is confident that the desirable effects (ie, benefits, such as improved health outcome) of an intervention/recommendation considerably outweigh the undesirable effects (ie, harms, such as adverse events) based on the available evidence. Strength is rated as strong (highly confident) or weak (less confident).15,23 † The GRADE quality of evidence rating is defined as the extent the panel can be certain that the true effect lies close to the effect estimates from a body of evidence supporting the recommendation and that further research is unlikely to change their confidence in the certainty. Quality is rated as high (high certainty), moderate (moderate certainty), low (low certainty), or very low (very low certainty).15,23 Source: Table adapted with permission from Kaminski et al.16 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Summary of key classification recommendations

|

Recommendation |

GRADE |

||||||||||||||

|

Strength* |

Quality† |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

In a person with a foot ulcer, as a minimum, use the SINBAD wound classification system. |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

In a person with an infected ulcer, use the IDSA/IWGDF infection classification system. |

Weak |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

In a person with an ulcer managed where expertise in vascular intervention is available, use the WIfI classification system. |

Weak |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

As a minimum, use the SINBAD system for any regional/national/international audits. |

Strong |

High |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

GRADE = Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; IDSA = Infectious Diseases Society of America; IWGDF = International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot; SINBAD = Site, Ischaemia, Neuropathy, Bacterial Infection, Area and Depth; WIfI = Wound, Ischaemia, and foot Infection. * The GRADE strength of recommendation rating is defined as the extent the panel is confident that the desirable effects (ie, benefits, such as improved health outcome) of an intervention or recommendation considerably outweigh the undesirable effects (ie, harms, such as adverse events) based on the available evidence. Strength is rated as strong (highly confident) or weak (less confident).15,23 † The GRADE quality of evidence rating is defined as the extent the panel can be certain that the true effect lies close to the effect estimates from a body of evidence supporting the recommendation and that further research is unlikely to change their confidence in the certainty. Quality is rated as high (high certainty), moderate (moderate certainty), low (low certainty), or very low (very low certainty).15,23 Source: Table adapted with permission from Hamilton et al.17 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Summary of key peripheral artery disease recommendations

|

Recommendation |

GRADE |

||||||||||||||

|

Strength* |

Quality† |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Examine all patients annually for PAD by taking a relevant history and palpating foot pulses. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

As examination does not reliably exclude PAD in persons with an ulcer, evaluate pedal Doppler arterial waveforms with ABI or TBI. PAD is less likely in presence of ABI of 0.9–1.3, TBI ≥ 0.75, and triphasic waveforms. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Perform at least one of the following in a patient with an ulcer and PAD, as any increases the probability of healing by > 25%: skin perfusion pressure ≥ 40 mmHg, toe pressure ≥ 30 mmHg, or TcPO2 ≥ 25 mmHg. |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

Use the WIfI classification system in a patient with an ulcer and PAD. |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

Always consider urgent vascular imaging/revascularisation in a patient with an ankle pressure < 50 mmHg, ABI < 0.5, toe pressure < 30 mmHg, or TcPO2 < 25 mmHg. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Always consider vascular imaging/revascularisation in patients, irrespective of the results of tests, when the ulcer is not healing within 6 weeks.‡ |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Use any of the following when considering revascularisation: colour duplex ultrasound, computed tomography angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, or intra‐arterial digital subtraction angiography. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

When performing revascularisation, aim to restore direct blood flow to at least one foot artery, preferably the artery that supplies the ulcer. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

As evidence is inadequate to establish which revascularisation technique is superior, make decisions based on individual factors, such as morphological distribution of PAD, availability of autogenous vein, the patient's comorbid conditions, and local expertise. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Any centre treating patients with ulcers should have expertise in, and/or rapid access to, facilities necessary to diagnose and treat PAD. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Ensure that after a revascularisation procedure, the patient is treated by a multidisciplinary team. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Urgently assess patients with signs of PAD and foot infection, as they are at particularly high risk for amputation. |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

Avoid revascularisation in patients in whom the risk–benefit ratio for success is unfavourable. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Provide intensive cardiovascular risk management for any patient with an ischaemic ulcer. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

ABI = ankle brachial index; GRADE = Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; PAD = peripheral artery disease; TBI = toe brachial index; TcPO2 = transcutaneous oxygen pressure; WIfI = Wound, Ischaemia, and foot Infection. * The GRADE strength of recommendation rating is defined as the extent to which the panel is confident that the desirable effects (ie, benefits, such as improved health outcome) of an intervention/recommendation considerably outweigh the undesirable effects (ie, harms, such as adverse events) based on the available evidence. Strength is rated as strong (highly confident) or weak (less confident).15,23 † The GRADE quality of evidence rating is defined as the extent to which the panel can be certain that the true effect lies close to the effect estimates from a body of evidence supporting the recommendation and that further research is unlikely to change their confidence in the certainty. Quality is rated as high (high certainty), moderate (moderate certainty), low (low certainty) or very low (very low certainty).15,23 ‡ Recommendation applying specifically to people with non‐healing diabetes‐related foot ulcers, defined as foot ulcers reducing in size by < 50% after four to six weeks of receiving best standard of foot ulcer care,26 in alignment with the applicable recommendations in these guidelines.16,17,18,19,20,21 Source: Table adapted with permission from Chuter et al.18 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Summary of key infection recommendations

|

Recommendation |

GRADE |

||||||||||||||

|

Strength* |

Quality† |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Diagnose soft tissue foot infection based on local or systemic signs and symptoms of inflammation. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Assess the severity of infection using the IWGDF/IDSA classification scheme. |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

Consider admitting to hospital all persons with severe infection (IWGDF/IDSA) and those with moderate infection that is complex. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

In a person with possible infection for whom examination is equivocal, consider an inflammatory serum biomarker for diagnosis, such as C‐reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or procalcitonin. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

In a person with suspected osteomyelitis, use probe‐to‐bone test, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (or C‐reactive protein and/or procalcitonin), and x‐rays as initial studies to diagnose osteomyelitis. |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

In a person with suspected osteomyelitis, if plain x‐ray and clinical and laboratory findings are compatible, we recommend no further imaging to establish diagnosis. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

If osteomyelitis remains in doubt, consider an advanced imaging study, such as magnetic resonance imaging, 18F‐FDG PET/CT, or leukocyte scintigraphy (with or without CT). |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

In a person with suspected osteomyelitis in whom making a definitive diagnosis or determining the causative pathogen is necessary for treatment, collect a bone sample for culture and histopathology. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Collect an appropriate specimen for culture for almost all clinically infected ulcers. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

For soft tissue infection, obtain a sample for culture by aseptically collecting a tissue specimen from the ulcer. |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

Treat a person with infection with an antibiotic shown to be effective in a randomised controlled trial that is appropriate for the individual. |

Strong |

High |

|||||||||||||

|

Select an antibiotic for treating infection based on causative pathogen(s) and antibiotic susceptibilities; clinical severity of infection; evidence of efficacy; risk of adverse events, including damage to commensal flora; likelihood of drug interactions; availability; and costs. |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

Administer antibiotic(s) initially by parenteral route to any patient with severe soft tissue infection. Switch to oral therapy if the patient is clinically improving, has no contraindications and if an appropriate agent is available. |

Strong |

Very low |

|||||||||||||

|

Treat patients with mild and most with moderate infections with oral antibiotic(s), either at presentation or when improving with intravenous therapy. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

We suggest not using topical antimicrobial(s) for treating mild infection. |

Weak |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

Administer antibiotic(s) to a patient with soft tissue infection for 1–2 weeks. |

Strong |

High |

|||||||||||||

|

Consider continuing for up to 3–4 weeks if the infection is improving but is extensive, resolving slower than expected, or if the patient has severe PAD. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

If infection has not resolved after 4 weeks, re‐evaluate and reconsider the need for further diagnostic studies or alternative treatments.‡ |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

For patients who have not recently received antibiotic(s) and have acute infection, consider targeting empiric antibiotic(s) at aerobic gram‐positive pathogens for mild infection. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

For patients who have been treated with antibiotic(s) within a few weeks, have a chronic infection, a severely ischaemic limb, or moderate or severe infection, we suggest selecting an empiric antibiotic that covers gram‐positive pathogens, commonly isolated gram‐negative pathogens, and possibly obligate anaerobes. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Empiric treatment aimed at Pseudomonas aeruginosa is not usually necessary but consider it if P. aeruginosa has been isolated from the site within the previous few weeks or in tropical/subtropical climates (at least for moderate or severe infection). |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Do not treat clinically uninfected ulcers with antibiotics. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Urgently consult with a surgical specialist in cases of severe infection or moderate infection complicated by extensive gangrene, necrotising infection, deep abscess, compartment syndrome, or severe PAD. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

In a patient with uncomplicated forefoot osteomyelitis, with no other indication for surgical treatment, consider treating with antibiotic(s) without surgical resection. |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

In a patient with probable osteomyelitis with soft tissue infection, urgently evaluate the need for surgery. |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

Select antibiotic(s) for treating osteomyelitis from those that have demonstrated efficacy in clinical studies. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Treat osteomyelitis with antibiotic(s) for just a few days if there is no soft tissue infection and all infected bone has been surgically removed. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

For osteomyelitis that initially requires parenteral therapy, consider switching to an appropriate oral antibiotic that has high bioavailability after 5–7 days. |

Weak |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

During surgery to resect bone for osteomyelitis, consider obtaining a bone specimen for culture (and, if possible, histopathology) at the stump of the resected bone to identify residual infection. |

Weak |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

If an aseptically collected culture specimen obtained during surgery grows pathogen(s) or if histology demonstrates osteomyelitis, administer appropriate antibiotic(s) for up to 6 weeks. |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

To specifically address infection, we suggest not using hyperbaric oxygen therapy nor topical oxygen therapy. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

To specifically address infection, we suggest not using adjunctive granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor treatment. |

Weak |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

To specifically address infection, we suggest not routinely using topical antiseptics, silver preparations, honey, bacteriophage therapy, or negative pressure wound therapy. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CT = computed tomography; 18F‐FDG = fluorine‐18 fluorodeoxyglucose; GRADE = Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; IDSA = Infectious Diseases Society of America; IWGDF = International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot; PAD = peripheral artery disease; PET = positron emission tomography. * The GRADE strength of recommendation rating is defined as the extent the panel is confident that the desirable effects (ie, benefits, such as improved health outcome) of an intervention/recommendation considerably outweigh the undesirable effects (ie, harms, such as adverse events) based on the available evidence. Strength is rated as strong (highly confident) or weak (less confident).15,23 † The GRADE quality of evidence rating is defined as the extent the panel can be certain that the true effect lies close to the effect estimates from a body of evidence supporting the recommendation and that further research is unlikely to change their confidence in the certainty. Quality is rated as high (high certainty), moderate (moderate certainty), low (low certainty), or very low (very low certainty).15,23 ‡ Recommendation applying specifically to people with non‐healing diabetes‐related foot ulcers, defined as foot ulcers reducing in size by < 50% after four to six weeks of receiving best standard of foot ulcer care,26 in alignment with the applicable recommendations in these guidelines.16,17,18,19,20,21 Source: Table adapted with permission from Commons et al.19 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Summary of key offloading recommendations

|

Recommendation |

GRADE |

||||||||||||||

|

Strength* |

Quality† |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

In a person with a neuropathic plantar forefoot/midfoot ulcer: |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Use a non‐removable knee‐high offloading device: |

Strong |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

When the above is contraindicated/not tolerated, consider a removable knee‐high offloading device |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

When the above is contraindicated/not tolerated, use a removable ankle‐high offloading device |

Strong |

Very low |

|||||||||||||

|

When the above is contraindicated/not tolerated, use medical‐grade footwear |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

If the best recommended offloading device option fails to heal a: |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Neuropathic plantar metatarsal head ulcer, consider Achilles tendon lengthening, gastrocnemius recession, metatarsal head resection(s), or joint arthroplasty‡ |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Neuropathic plantar ulcer on a non‐rigid toe, consider a digital flexor tenotomy‡ |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

In a person with a neuropathic plantar forefoot/midfoot ulcer (complicated) with: |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Mild infection and mild ischaemia, moderate infection or moderate ischaemia, consider a removable knee‐high offloading device |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Moderate infection and moderate ischaemia, severe infection or severe ischaemia, consider a removable offloading intervention |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

In a person with a neuropathic plantar heel ulcer, consider a knee‐high offloading device |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

In a person with a non‐plantar ulcer use a removable offloading device, medical‐grade footwear, felted foam, toe spacers or orthoses, depending on the ulcer type and location |

Strong |

Very low |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

GRADE = Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation. * The GRADE strength of recommendation rating is defined as the extent the panel is confident that the desirable effects (ie, benefits, such as improved health outcome) of an intervention/recommendation considerably outweigh the undesirable effects (ie, harms, such as adverse events) based on the available evidence. Strength is rated as strong (highly confident) or weak (less confident).15,23 † The GRADE quality of evidence rating is defined as the extent the panel can be certain that the true effect lies close to the effect estimates from a body of evidence supporting the recommendation and that further research is unlikely to change their confidence in the certainty. Quality is rated as high (high certainty), moderate (moderate certainty), low (low certainty), or very low (very low certainty).15,23 ‡ Recommendation applying specifically to people with non‐healing diabetes‐related foot ulcers, defined as foot ulcers reducing in size by < 50% after four to six weeks of receiving best standard of foot ulcer care,26 in alignment with the applicable recommendations in these guidelines.16,17,18,19,20,21 Source: Table adapted with permission from Fernando et al.20 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 6 – Summary of key wound healing recommendations

|

Recommendation |

GRADE |

||||||||||||||

|

Strength* |

Quality† |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Remove slough, necrotic tissue, and callus of an ulcer with sharp debridement, taking relative contraindications into account. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Dressings should be selected principally on exudate control, comfort and cost. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Do not use dressings/applications containing surface antimicrobial agents with the sole aim of accelerating the healing of an ulcer. |

Strong |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Consider sucrose octasulfate‐impregnated dressing in non‐infected, neuro‐ischaemic ulcers that are difficult to heal.‡ |

Weak |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

Consider systemic hyperbaric oxygen therapy in non‐healing ischaemic ulcers.‡ |

Weak |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

We suggest not using topical oxygen therapy. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Consider negative pressure wound therapy in patients with a surgical wound. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

We suggest not using negative pressure wound therapy in non‐surgical ulcers. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Consider placental‐derived products in ulcers that are difficult to heal.‡ |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

We suggest not using growth factors, autologous platelet gels, bioengineered skin products, ozone, topical carbon dioxide, and nitric oxide. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

Consider autologous combined leucocyte, platelet and fibrin in non‐infected ulcers that are difficult to heal, if approved in Australia.‡ |

Weak |

Moderate |

|||||||||||||

|

We suggest not using agents including electricity, magnetism, ultrasound and shockwaves. |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

We suggest not using interventions aimed at correcting nutritional status (including supplementation of protein, vitamins, trace elements). |

Weak |

Low |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

GRADE = Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation. * The GRADE strength of recommendation rating is defined as the extent the panel is confident that the desirable effects (ie, benefits, such as improved health outcome) of an intervention/recommendation considerably outweigh the undesirable effects (ie, harms, such as adverse events) based on the available evidence. Strength is rated as strong (highly confident) or weak (less confident).15,23 † The GRADE quality of evidence rating is defined as the extent the panel can be certain that the true effect lies close to the effect estimates from a body of evidence supporting the recommendation and that further research is unlikely to change their confidence in the certainty. Quality is rated as high (high certainty), moderate (moderate certainty), low (low certainty), or very low (very low certainty).15,23 ‡ Recommendation applying specifically to people with non‐healing diabetes‐related foot ulcers, defined as foot ulcers reducing in size by < 50% after four to six weeks of receiving best standard of foot ulcer care,26 in alignment with the applicable recommendations in these guidelines.16,17,18,19,20,21 Source: Table adapted with permission from Chen et al.21 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 7 – Prevention pathway for a person with diabetes at risk of foot ulceration*

* Using this pathway: This figure incorporates all 15 recommendations made in the Australian guideline on prevention of foot ulceration16 into an evidence‐based clinical pathway. The pathway aims to guide the health professional through screening, education and treatment according to the person's risk category for developing foot ulceration (very low, low, moderate or high risk). This pathway should be read in the following order:

1. Screening (left column): Examine for stated risk factors for developing foot ulceration (higher boxes). Use identified risk factors to categorise the person's risk category according to the IWGDF Risk Stratification System (lower box). Use the person's risk category to determine the frequency of re‐examination (middle boxes).

2. Education (middle column): Provide stated education to all persons at‐risk (low, moderate or high risk; higher boxes), plus also consider additional stated education for persons at moderate or high risk (lower boxes).

3. Treatment (right column): Provide stated treatments to all persons at‐risk (low, moderate or high risk) (higher boxes), plus also consider additional stated treatments for persons at moderate or high risk (lower boxes).

Source: Figure reproduced with permission from the Diabetes and Feet Toolkit (version 1; February 2022); National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS), an initiative of the Australian Government and is administered by Diabetes Australia (https://www.ndss.com.au/about‐diabetes/resources/find‐a‐resource/diabetes‐and‐feet‐toolkit/).45

Box 8 – Wound classification pathway for any person presenting with a diabetes‐related foot ulcer*

IDSA = Infectious Diseases Society of America; IWGDF = International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot.* Using this pathway: This figure incorporates all five recommendations made in the Australian guideline on wound classification of diabetes‐related foot ulcers into an evidence‐based clinical pathway.16 The pathway aims to guide the health professional through assessing and classifying a person presenting with a diabetes‐related foot ulcer, and also refers to the management pathways needed. This pathway should be read in the following order:

1. Assessing medical history (first row): Obtain stated medical history factors relevant for a person with a diabetes‐related foot ulcer.

2. Classifying ulcer (second row): Examine for stated ulcer characteristics that are required at a minimum to classify the person's ulcer according to the SINBAD classification system (left box). Use identified characteristics to communicate ulcer status with other health professionals (right box). Further examine people with signs of peripheral artery disease or infection according to the Wound, Ischaemia, and foot Infection (WIfI) or IDSA/IWGDF classification systems respectively (third row).

3. Providing management (fourth row): Provide all persons with diabetes‐related foot ulcers management according to the wound healing intervention and offloading management pathways (left boxes), plus, also provide people with signs of PAD or infection management according to the PAD and infection management pathways respectively (right boxes).

Source: Figure reproduced with permission from the Diabetes and Feet Toolkit (version 1; February 2022); National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS), an initiative of the Australian Government and is administered by Diabetes Australia (https://www.ndss.com.au/about‐diabetes/resources/find‐a‐resource/diabetes‐and‐feet‐toolkit/).45

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Peter A Lazzarini1,2

- Anita Raspovic3

- Jenny Prentice4

- Robert J Commons5,6

- Robert A Fitridge7,8

- James Charles9

- Jane Cheney10

- Nytasha Purcell11

- Stephen M Twigg12,13

- 1 Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD

- 2 Allied Health Research Collaborative, Metro North Hospital and Health Service, Brisbane, QLD

- 3 La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC

- 4 Hall and Prior Health and Aged Care Group, Perth, WA

- 5 Grampians Rural Health Alliance, Ballarat, VIC

- 6 Menzies School of Research, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT

- 7 Royal Adelaide Hospital, Adelaide, SA

- 8 University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA

- 9 First Peoples Health Unit, Griffith University, Gold Coast, QLD

- 10 Diabetes Victoria, Melbourne, VIC

- 11 Diabetes Feet Australia, Australian Diabetes Society, Sydney, NSW

- 12 University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 13 Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, NSW

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Queensland University of Technology, as part of the Wiley ‐ Queensland University of Technology agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

We acknowledge the assistance of the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) Guideline Editorial Board for providing permission for us to adapt the IWGDF guidelines for the purpose of these new Australian guidelines. We also acknowledge the assistance of the Journal of Foot and Ankle Research for providing permission to summarise the individual guidelines that make up the Australian evidence‐based guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes‐related foot disease into this guideline summary. In addition, we acknowledge the assistance of the National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS) for providing permission to re‐publish the clinical pathways that were developed as part of the Diabetes and Feet Toolkit that was funded through the NDSS. The NDSS is an initiative of the Australian Government and is administered by Diabetes Australia. Peter Lazzarini has received support by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowship (1143435) and Robert Commons by an Australian NHMRC Emerging Leader Investigator Grant (1194702). Lastly, we acknowledge the 30 national expert panel members that so kindly volunteered their valuable time to develop each new Australian guideline that is summarised in this manuscript. The list of names of all panel members can be found in the published protocol guideline. The funding and supporting bodies provided oversight for this guideline but did not have any input into the decisions on the methodology, findings or any specific recommendations contained in these guidelines or in the writing of these guidelines.

The Australian Diabetes‐related Foot Disease Guidelines and Pathways Project received partial funding from the National Diabetes Services Scheme and in‐kind secretariat support and oversight from Diabetes Feet Australia and the Australian Diabetes Society. The funding/supporting bodies provided oversight for this guideline but did not have any input into the decisions on the methodology, findings or any specific recommendations contained in these guidelines or in the writing of these guidelines.

- 1. Lazzarini PA, van Netten JJ, Fitridge R, et al. Pathway to ending avoidable diabetes‐related amputations in Australia. Med J Aust 2018; 209: 288‐290. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2018/209/7/pathway‐ending‐avoidable‐diabetes‐related‐amputations‐australia?check_logged_in=1

- 2. van Netten JJ, Lazzarini PA, Fitridge R, Kinnear EM, et al. Australian Diabetes‐Related Foot Disease Strategy 2018–2022: the first step towards ending avoidable amputations within a generation. Brisbane: Wound Management CRC; 2017. https://www.diabetesfeetaustralia.org/wp‐content/uploads/2020/12/Australian‐diabetes‐related‐foot‐disease‐strategy‐2018‐2022‐DFA2020.pdf?_gl=1*v3rc45*_ga*MTg5NzU2NzUxLjE2ODE5NDg2Njg.*_up*MQ (viewed Apr 2023).

- 3. Zhang Y, Lazzarini PA, McPhail SM, et al. Global disability burdens of diabetes‐related lower‐extremity complications in 1990 and 2016. Diabetes Care 2020; 43: 964‐974.

- 4. Zhang Y, van Netten JJ, Baba M, et al. Diabetes‐related foot disease in Australia: a systematic review of the prevalence and incidence of risk factors, disease and amputation in Australian populations. J Foot Ankle Res 2021; 14: 8.

- 5. Quigley M, Morton JI, Lazzarini PA, et al. Trends in diabetes‐related foot disease hospitalizations and amputations in Australia, 2010 to 2019. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2022; 194: 110189.

- 6. Lazzarini PA, Cramb SM, Golledge J, et al. Global trends in the incidence of hospital admissions for diabetes‐related foot disease and amputations: a review of national rates in the 21st century. Diabetologia 2023; 66: 267‐287.

- 7. West M, Chuter V, Munteanu S, Hawke F. Defining the gap: a systematic review of the difference in rates of diabetes‐related foot complications in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and non‐Indigenous Australians. J Foot Ankle Res 2017; 10: 48.

- 8. Lazzarini PA, O'Rourke SR, Russell AW, et al. reduced incidence of foot‐related hospitalisation and amputation amongst persons with diabetes in Queensland, Australia. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0130609.

- 9. Kurowski JR, Nedkoff L, Schoen DE, et al. Temporal trends in initial and recurrent lower extremity amputations in people with and without diabetes in Western Australia from 2000 to 2010. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015; 108: 280‐287.

- 10. Baba M, Davis WA, Norman PE, Davis TM. Temporal changes in the prevalence and associates of diabetes‐related lower extremity amputations in patients with type 2 diabetes: the Fremantle Diabetes Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2015; 14: 152.

- 11. Zhang Y, Carter HE, Lazzarini PA, et al. Cost‐effectiveness of guideline‐based care provision for patients with diabetes‐related foot ulcers: a modelled analysis using discrete event simulation. Diabet Med 2023; 40: e14961.

- 12. Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute. National evidence‐based guideline on prevention, identification and management of foot complications in diabetes (part of the Guidelines on Management of Type 2 Diabetes) Melbourne: Baker IDI, 2011. https://www.baker.edu.au/impact/guidelines/guideline‐foot‐complication (viewed Apr 2023).

- 13. Parker CN, van Netten JJ, Parker TJ, et al. Differences between national and international guidelines for the management of diabetic foot disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2019; 35: e3101.

- 14. Deng P, Shi H, Pan X, et al. Worldwide research trends on diabetic foot ulcers (2004–2020): suggestions for researchers. J Diabetes Res 2022; 2022: 7991031.

- 15. Lazzarini PA, Raspovic A, Prentice J, et al. Guidelines development protocol and findings: part of the 2021 Australian evidence‐based guidelines for diabetes‐related foot disease. J Foot Ankle Res 2022; 15: 28.

- 16. Kaminski MR, Golledge J, Lasschuit JWJ, et al. Australian guideline on prevention of foot ulceration: part of the 2021 Australian evidence‐based guidelines for diabetes‐related foot disease. J Foot Ankle Res 2022; 15: 53.

- 17. Hamilton EJ, Scheepers J, Ryan H, et al. Australian guideline on wound classification of diabetes‐related foot ulcers: part of the 2021 Australian evidence‐based guidelines for diabetes‐related foot disease. J Foot Ankle Res 2021; 14: 60.

- 18. Chuter V, Quigley F, Tosenovsky P, et al. Australian guideline on diagnosis and management of peripheral artery disease: part of the 2021 Australian evidence‐based guidelines for diabetes‐related foot disease. J Foot Ankle Res 2022; 15: 51.

- 19. Commons RJ, Charles J, Cheney J, et al. Australian guideline on management of diabetes‐related foot infection: part of the 2021 Australian evidence‐based guidelines for diabetes‐related foot disease. J Foot Ankle Res 2022; 15: 47.

- 20. Fernando ME, Horsley M, Jones S, et al. Australian guideline on offloading treatment for foot ulcers: part of the 2021 Australian evidence‐based guidelines for diabetes‐related foot disease. J Foot Ankle Res 2022; 15: 31.

- 21. Chen P, Carville K, Swanson T, et al. Australian guideline on wound healing interventions to enhance healing of foot ulcers: part of the 2021 Australian evidence‐based guidelines for diabetes‐related foot disease. J Foot Ankle Res 2022; 15: 40.

- 22. National Health and Medical Research Council. Guidelines for guidelines: adopt, adapt or start from scratch [version 5.2. Canberra: NHMRC, 2018. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelinesforguidelines/plan/adopt‐adapt‐or‐start‐scratch (viewed Apr 2023).

- 23. Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Brozek J, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE‐ADOLOPMENT. J Clin Epidemiol 2017; 81: 101‐110.

- 24. ADAPTE Collaboration. The ADAPTE process: resource toolkit for guideline adaptation — version 2.0. Perthshire, Scotland: Guideline International Network; 2009. https://g‐i‐n.net/get‐involved/resources/ (viewed Apr 2023).

- 25. van Netten JJ, Bus SA, Apelqvist J, et al. Definitions and criteria for diabetic foot disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3268.

- 26. Jeffcoate WJ, Bus SA, Game FL, et al. Reporting standards of studies and papers on the prevention and management of foot ulcers in diabetes: required details and markers of good quality. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016; 4: 781‐788.

- 27. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010; 182: E839‐E842.

- 28. Bus SA, van Netten JJ, Hinchliffe RJ, et al. Standards for the development and methodology of the 2019 International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot guidelines. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3267.

- 29. Bus SA, Lavery LA, Monteiro‐Soares M, et al. Guidelines on the prevention of foot ulcers in persons with diabetes (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3269.

- 30. Monteiro‐Soares M, Russell D, Boyko EJ, et al. Guidelines on the classification of diabetic foot ulcers (IWGDF 2019). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3273.

- 31. Bus SA, Armstrong DG, Gooday C, et al. Guidelines on offloading foot ulcers in persons with diabetes (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3274.

- 32. Hinchliffe RJ, Forsythe RO, Apelqvist J, et al. Guidelines on diagnosis, prognosis, and management of peripheral artery disease in patients with foot ulcers and diabetes (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3276.

- 33. Lipsky BA, Senneville E, Abbas ZG, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of foot infection in persons with diabetes (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3280.

- 34. Rayman G, Vas PR, Dhatariya KK, et al. Guidelines on use of interventions to enhance healing of chronic foot ulcers in diabetes (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3283.

- 35. Forsythe RO, Apelqvist J, Boyko EJ, et al. Effectiveness of revascularisation of the ulcerated foot in patients with diabetes and peripheral artery disease: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3279.

- 36. Forsythe RO, Apelqvist J, Boyko EJ, et al. Effectiveness of bedside investigations to diagnose peripheral artery disease among people with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3277.

- 37. Forsythe RO, Apelqvist J, Boyko EJ, et al. Performance of prognostic markers in the prediction of wound healing or amputation among patients with foot ulcers in diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3278.

- 38. Lazzarini PA, Jarl G, Gooday C, et al. Effectiveness of offloading interventions to heal foot ulcers in persons with diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3275.

- 39. Monteiro‐Soares M, Boyko EJ, Jeffcoate W, et al. Diabetic foot ulcer classifications: a critical review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3272.

- 40. Peters EJG, Lipsky BA, Senneville É, et al. Interventions in the management of infection in the foot in diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3282.

- 41. Senneville É, Lipsky BA, Abbas ZG, et al. Diagnosis of infection in the foot in diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3281.

- 42. van Netten JJ, Raspovic A, Lavery LA, et al. Prevention of foot ulcers in the at‐risk patient with diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3270.

- 43. van Netten JJ, Sacco ICN, Lavery LA, et al. Treatment of modifiable risk factors for foot ulceration in persons with diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3271.

- 44. Vas P, Rayman G, Dhatariya K, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to enhance healing of chronic foot ulcers in diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2020; 36 (Suppl): e3284.

- 45. National Diabetes Services Scheme. Diabetes and feet: a practical toolkit for health professionals using the Australian diabetes‐related foot disease guidelines. Canberra: NDSS, 2022. https://www.ndss.com.au/about‐diabetes/resources/find‐a‐resource/diabetes‐and‐feet‐toolkit/ (viewed Apr 2023).

- 46. Zhang Y, Cramb S, McPhail SM, et al. Factors associated with healing of diabetes‐related foot ulcers: observations from a large prospective real‐world cohort. Diabetes Care 2021; 44: e143‐e145.

Abstract

Introduction: Diabetes‐related foot disease (DFD) — foot ulcers, infection, ischaemia — is a leading cause of hospitalisation, disability, and health care costs in Australia. The previous 2011 Australian guideline for DFD was outdated. We developed new Australian evidence‐based guidelines for DFD by systematically adapting suitable international guidelines to the Australian context using the ADAPTE and GRADE approaches recommended by the NHMRC.

Main recommendations: This article summarises the most relevant of the 98 recommendations made across six new guidelines for the general medical audience, including:

Changes in management as a result of the guideline: For people without DFD, key changes include using a new risk stratification system for screening, categorising risk and managing people at increased risk of DFD. For those categorised at increased risk of DFD, more specific self‐monitoring, footwear prescription, surgical treatments, and activity management practices to prevent DFD have been recommended. For people with DFD, key changes include using new ulcer, infection and PAD classification systems for assessing, documenting and communicating DFD severity. These systems also inform more specific PAD, infection, pressure offloading, and wound healing management recommendations to resolve DFD.