In the words of renowned American surgeon, writer and public health researcher Dr Atul Gawande, “The core predicament of medicine — the thing that makes being a patient so wrenching, being a doctor so difficult, and being a part of society that pays the bills they run up so vexing — is uncertainty … Medicine's ground state is uncertainty. And wisdom — for both the patients and doctors — is defined by how one copes with it”.1

The ever‐increasing novelty, complexity and, sometimes, insolubility of modern medicine brings decisional uncertainty for clinicians (Box 1). Although diagnostic conundrums attract considerable attention, uncertainty pervades many other areas of practice, such as how to deal with incidental or ambiguous findings from an ever‐increasing array of laboratory investigations,2 what treatments to prescribe for conditions for which there are multiple options,3 how to predict illness trajectories and navigate the care of patients through a complex health system,4 and how to ethically decide what care to provide while reconciling patient wishes with likelihood of benefit and limited resource availability.5 In addition, scientific evidence is non‐existent, conflicting, inconclusive or not applicable for many clinical questions, so deciding what constitutes best care in a particular set of circumstances remains uncertain (epistemic uncertainty).6 Equally, even with high quality evidence, it can be difficult to predict the effects of interventions in individual patients (aleatory uncertainty).7 Contextual factors can also inject more uncertainty into clinical encounters by disrupting reasoning processes, these being clinician‐related (eg, fatigue, hunger), patient‐related (eg, poor English proficiency, presentation complexity) or environment‐related (eg, noise, distractions, time pressures).8

Despite the ubiquity of uncertainty in medicine, clinical culture too often fails to acknowledge it, explore how it affects individual clinicians, or consider what can be done to mitigate it.9 Professional training and socialisation have traditionally placed value on certainty over uncertainty,10 and how to minimise or eliminate uncertainty rather than in how to tolerate or manage it. Clinicians respond to uncertainty in various ways through the interplay of a series of cognitive, emotional and ethical reactions.11 Stress from uncertainty is increasingly recognised as a likely driver of professional burnout in health care,12 reducing clinician engagement and productivity, posing risks for patient safety as a result of more errors,13 and exacerbating workforce shortages by inducing early retirement or change of occupation.14 Acquiring the adaptive ability to understand and tolerate clinical uncertainty and guide patients in trusting relationships amid such uncertainty are important challenges facing clinicians,1,15 and are now recognised as core clinical competencies for medical graduates and trainees.16 Modern computerised decision support systems currently lack intelligent inference mechanisms for handling uncertainties in scientific knowledge and its application to specific clinical scenarios.17 Evidence‐based clinical decision rules do not necessarily improve care processes or patient outcomes,18 and although precision medicine using artificial intelligence, machine learning and big data seeks to lend greater certainty in personalising care, the information explosion that it brings will likely increase rather than decrease levels of uncertainty.19

The aims of this narrative review are to: i) characterise the various types of uncertainty; ii) define the adverse effects, clinician characteristics and clinical contexts associated with intolerance of uncertainty; iii) identify means for assessing intolerance of uncertainty at an individual level; and iv) present strategies that clinicians and their patients can use to cope with uncertainty after doing what can be reasonably done to minimise it. This review is based on original articles and systematic or narrative reviews obtained from a search of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, SocINDEX, CINAHL, Web of Science and Google Scholar published between 1 January 1995 and 30 September 2022 using search terms “uncertainty”, “ambiguity”, “tolerance”, “confidence” and “coping”. We selected articles relating to clinicians providing direct patient care and excluded those relating to more indirect care provided by clinicians in disciplines such as pathology and radiology.

Characterising clinical uncertainty

As there is no universal definition of clinical uncertainty, we will define it simply as the state clinicians are in when they are unsure of the diagnosis, the care to be recommended and delivered, or their understanding of the patient, their problem, or its trajectory. Clinical uncertainty is common, with one study of doctors interacting with older male patients verbally expressing uncertainty in up to 70% of all encounters.20 In primary care, one British study of 50 new patients presenting with a diagnostic issue revealed a certain diagnosis was forthcoming by the end of the first consultation in less than half of the cases.21 Among 592 patients presenting acutely with dyspnoea to one emergency department in the United States, almost a third of cases remained undiagnosed after a full standard work‐up.22

Not surprisingly, clinical uncertainty can take various forms according to the decisional context and goals, as denoted by various conceptual frameworks and taxonomies of uncertainty. An initial framework proposed three types of informational uncertainty: technical (due to limited scientific data or practical skill), personal (arising from gaps in understanding patients’ wishes), and conceptual (resulting from the application of abstract criteria, such as guideline recommendations or protocols, to concrete clinical scenarios).23 Another framework states uncertainty can be about the research evidence, the patient's story, what best to do for a specific patient with a particular set of circumstances, and the interactions between humans and between humans and technology.24 A third framework classifies uncertainty as being centred on probability (ie, inability to predict future outcomes), ambiguity (ie, lack of information or conflicting evidence or opinion) or complexity (ie, multiplicity of causal factors, relationships and interpretations).25 The same authors also identify loci of uncertainty as being disease‐centred (diagnosis, prognosis, treatments), system‐centred (structures and processes of care, networking, teamwork) and patient‐centred (psychosocial and existential effects of illness and its treatment on patients’ perceived meaning of life and personal relationships). A fourth framework similarly categorises uncertainty as arising primarily from deficits in scientific knowledge about disease, insufficient practical understanding of how systems of care operate (eg, lack of clarity about expected skills, how to access or implement different forms of care, what policies and procedures to follow), and inability to predict the aforementioned effects of illness and treatments on patients.26 However, this framework also includes ethical aspects of clinicians reconciling their personal values with those of their patients and with the sociocultural and practice codes of the craft groups and institutions within which they work.

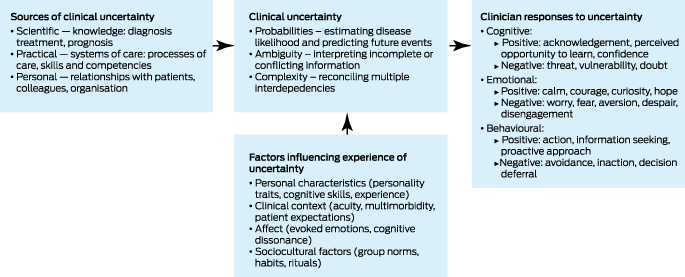

More recently, different researchers have formulated frameworks that not only identify the types and sources of uncertainty, but also include factors that influence how much an individual clinician perceives uncertainty (eg, the clinical context or situation, personal moderators such as personality, cognitive capacity, level of experience, sociocultural influences), and categorise how individuals respond to uncertainty in cognitive, emotional and behavioural terms, both positive and negative.27,28,29 In Box 2, we have constructed a schema that integrates these various frameworks, while noting that dimensions of probability, ambiguity and complexity can be difficult to disentangle, and boundaries between source domains of scientific, practical and personal, and between response domains of cognitive, emotional and behavioural are blurry and often intertwined.

Effects of uncertainty on clinicians and patient care

Like all humans, clinicians will often think and do things in an attempt to extract themselves from situations of uncertainty which are experienced as being uncomfortable or even stressful. When confronted with uncertainty in decision making, clinicians may deny it and apply accepted rituals, simply adopt the practice of their peers, or rely on heuristic reasoning (use of mental shortcuts or rules of thumb).30 In other instances, acknowledging uncertainty may serve as a self‐protective or motivational force, resulting in increased information seeking or considered selection of preventive, diagnostic and therapeutic actions.

Unfortunately, maladaptive reactions induced by an intolerance of uncertainty and desire for decisional comfort can have adverse consequences for patient care. Clinicians with higher intolerance of uncertainty may be more likely to avoid certain kinds of patients with complex needs, such as substance users, the poor, older patients and the underserved, contributing to health inequities.31 Studies show that intolerance of uncertainty can impair clinical decision‐making skills,32 manifesting as misperceptions of clinical goals of care, greater vulnerability to reasoning biases (eg, premature closure in diagnostic reasoning) and lower diagnostic performance,33 overuse and misuse of diagnostic tests,34 prescribing of inappropriate interventions,35 more unnecessary referrals,36 and reduced engagement with colleagues and patients in decision making.32,37 This can all result in compromised doctor–patient relationships and decreased patient satisfaction, confidence and trust in the medical system.38

Intolerance of uncertainty is also associated with more psychological distress and burnout,8,39 loss of self‐compassion,40 career dissatisfaction and disengagement at work, more discomfort dealing with death and grief,41 more concerns about malpractice risk, less propensity to adopt new and effective clinical interventions,32 and more limited leadership abilities.42 Clinicians with higher intolerance of uncertainty may also avoid certain career paths, such as primary care, emergency medicine, psychiatry or geriatric medicine, as these are perceived as disciplines likely to evoke more decisional uncertainty.14,32,43

Personal and contextual factors associated with intolerance of uncertainty

Evidence of any associations between intolerance of uncertainty and clinician and contextual factors is, to date, inconsistent, although some studies suggest a higher propensity towards intolerance of uncertainty among female clinicians,37 general practitioners,37 and surgeons.44 Clinicians with more experience or who are less risk‐averse tolerate uncertainty more than less experienced37,45 or more risk‐averse46 colleagues, and lacking a trusted advisor is also associated with greater intolerance of uncertainty.37

Regarding contextual influences, clinicians are less tolerant of uncertainty when dealing with acute undifferentiated clinical scenarios, especially in settings where access to advice is reduced,46,47 or when interviewing more educated persons who show a greater desire for information,48 or with patients who present with mental health or psychosocial issues rather than biomedical ones.49 Other patient characteristics such as age, gender or race appear to exert no influence.

Assessing individual tolerance of uncertainty and response

In measuring a clinician's level of intolerance of uncertainty and response, the 1995 version of the Physician's Reactions to Uncertainty (PRU) scale is the most widely cited and validated tool (Box 3).50 This 15‐item, Likert‐scale questionnaire has two parts, the first assessing the level of stress arising from uncertainty in terms of anxiety and concerns about bad outcomes, and the second determining the extent to which uncertainty results in reluctance to disclose uncertainty to patients or disclose mistakes to other clinicians. The points for each item are summed to give a final score, with a higher score indicating greater intolerance of uncertainty. The PRU scale is limited in that it addresses only emotional reactions to uncertainty, rather than those of a cognitive and ethical nature.9,37

The PRU scale helps to identify different clinician phenotypes in terms of affective and maladaptive response to intolerance of uncertainty. In one cross‐sectional analysis of 1209 clinical encounters involving 594 Australian general practice trainees to whom the PRU scale was applied,51 the anxiety and concern subscales were associated with female gender, less experience in hospital before commencing general practice training, and graduation overseas. On the other hand, the reluctance to disclose subscale was associated with urban practice, health qualifications before studying medicine, practice in an area of higher socio‐economic status, and being trained in Australia.

Strategies for managing uncertainty

As tolerance of uncertainty is thought, at least partly, to be determined by situational factors, it may be amenable to change through educational and experiential processes. Much of the research on such processes involves novice clinicians (medical students, residents, trainees or newly qualified specialists), although the insights gained have application to all grades of experience. At the outset, novice clinicians should expect uncertainty to be part of their routine work, and manage the expectations of all parties involved in delivering care, including themselves, about how much they are capable of eliminating it.52 Where uncertainty results from limited knowledge and experience, information‐seeking actions can be constructive, but, at some point, clinicians have to accept they will never know everything they need to know and no amount of study or decision support will eliminate uncertainty.

Evidence is emerging of the value of incorporating formal teaching in how to characterise uncertainty and how to cope with it into undergraduate and postgraduate curricula, best integrated with courses in clinical reasoning.53 Various educational formats have been shown to have favourable impact, including clinical debriefs, small group exercises, role plays, simulations, standardised cases, chart‐stimulated recall interviews, peer‐to‐peer conversations, and reflective learning and assessment, including narratives from mentoring clinicians which express and normalise their own vulnerability to uncertainty.46,54,55,56 Discussing uncertainty with members of multidisciplinary teams allows others to offer advice and perspectives that can decrease errors and cognitive overload.57 Commitment to lifelong learning and intellectual curiosity are also strengths, as researching a patient's illness and possibly becoming aware of new case reports or new treatments may benefit existing or future patients.

However, others argue the acquisition of appropriate reactions to uncertainty will mostly occur over time with more experience.58 In reality, a complex balance of education and experience is most likely, while recognising that fixed personality traits and deeply imprinted prior experiences may predispose individuals to specific psychological responses.59 Of concern is the observation in some studies of medical students becoming more intolerant of ambiguity, losing empathy and seeking decisional perfectionism as they progress through their course.43,60,61

Acting with confidence while simultaneously remaining uncertain in dealing with complex, ill‐defined problems epitomises expert practice. In such situations, clinicians continuously reconstruct and redefine their understanding of the problem, even as they are trying to solve it.62 This goal of becoming comfortable with uncertainty and remaining able to make decisions is different to being certain but uncomfortable, where one perceives a clear understanding of the problem but realises one is incapable of managing it. Clinicians with intolerance of uncertainty often perceive uncertainty as a threat to self‐identity, and in reducing such existential distress, cognitive dissonance provoked by uncertainty must be transformed into self‐directed learning moments, whereby clinicians become aware of, and are shown how to lower, perceived threats while improving resilience.63 Recent articles offer various strategies for coping with uncertainty in routine practice,64,65,66,67 as summarised in Box 4.

Communicating uncertainty with patients

In an era of shared decision making, whether to share uncertainty with patients is not the issue, rather the question is how best to communicate it without causing undue anxiety or loss of trust, which both become more likely the longer uncertainty persists.68 Clinicians who perceive their patients as more likely to have negative reactions to uncertainty may make unilateral and premature decisions about preferred care and withhold interventions where there is uncertainty about benefits and harms.69 In contrast, disclosing and managing uncertainty may actually strengthen the therapeutic clinician–patient relationship depending on how uncertainty is communicated, and what strategies are used to prioritise continuity of care, patient‐centred communication, and trust.70 Acknowledging uncertainty and exercising appropriate safety netting build patient confidence in their clinician's care, contrary to beliefs that such admissions may imperil clinician credibility and authority.15 Instructing a patient to call if any change or clinical worsening occurs and being specific about what the patient should look for and how to seek medical attention build patient trust and confidence. Similarly, sharing uncertainty with colleagues applies when patients are being discharged from hospital. The clinician who will assume follow‐up (likely the patient's general practitioner) should be contacted directly by the inpatient team, and any uncertainty regarding the patient's diagnosis or plans of care should be made clear. The same principle applies during a hospitalisation, as care is transitioned from one shift to another or from one clinician to another.

Despite the growth in studies exploring multiple sources and types of uncertainty, most continue to focus on identifying, testing and evaluating strategies to communicate probabilistic risk.70 This may not always be appropriate due to the increasing realisation of limitations in scientific evidence and a multiplicity of alternative care options. Consequently, more focus needs to be given to improving communication of uncertainty inherent in ambiguous and complex scenarios.70 Box 5 provides a structured approach to communicating uncertainty to patients based on findings from recent reviews.71,72,73,74 However, successfully enacting this approach requires both clinicians and patients to be free of time pressures, distractions and competing priorities.

Conclusion

Uncertainty is intrinsic to clinical practice, affecting both trainees and experienced clinicians. As Sir William Osler wrote: “Medicine is the science of uncertainty and the art of probability”.75 Limitations in knowledge, complexities of care, and variation in patient preferences contribute to uncertainty. Personal factors such as personality traits and resilience influence one's tolerance of uncertainty and responses to it. Clinicians need to be able to recognise and manage uncertainty in its various forms, communicate uncertainty to patients, and normalise and openly discuss clinical uncertainty with their peers. At the same time, the current design and funding of health care favour investigations and procedures over potentially lengthy and cognitively demanding discussions between clinicians and patients and shared decision making in the context of irreducible clinical uncertainty. Clinicians and managers must together advocate for system of care reforms that support the recognition, acceptance and management of uncertainty, and the means for minimising its potentially harmful effects on patient care and clinician wellbeing.

Box 1 – Examples of clinical uncertainty

|

Type of uncertainty |

Example |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Diagnostic |

Child with irritability and fever — is it meningitis? |

||||||||||||||

|

Older patient with exertional dyspnoea and who is overweight, smokes and has cardiac risk factors — is it heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or deconditioning? |

|||||||||||||||

|

Therapeutic |

Patient with reduced exercise tolerance, fatigue and “brain fog” post‐ coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) — what treatments may help? |

||||||||||||||

|

Older multimorbid patient with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, Parkinson disease, polypharmacy, and declining function — will starting a new drug to treat one of these conditions make another condition worse?, will ceasing a drug potentially improve or worsen their clinical state? |

|||||||||||||||

|

Prognostic |

Patient with a new presentation of depression — are they suicidal and is there an increased risk of suicide if they are started on an antidepressant? |

||||||||||||||

|

Older frail patient with hearing impairment presenting for driving assessment — are they fit to drive for another year? |

|||||||||||||||

|

Investigational |

Patient with unintentional weight loss and fatigue but no other specific symptoms or signs — what tests will be most useful in diagnosing underlying disease? |

||||||||||||||

|

Otherwise well person presenting with mild cough and elevated white cell count — is further investigation required? |

|||||||||||||||

|

Interpretive |

Patient with slight enlargement of retroperitoneal lymph glands found incidentally on abdominal computed tomography scan performed to investigate flank pain — is this pathological? |

||||||||||||||

|

Supportive |

Older frail patient living alone who is cognitively impaired and presents with recurrent falls — will a home care package be sufficient or do they need residential aged care? |

||||||||||||||

|

Triaging |

Patient with cardiac risk factors who presents following an episode of retrosternal chest pain, but has normal physical examination and electrocardiogram — should they be referred immediately to an emergency department or urgently to a chest pain clinic, or should they be closely monitored by their general practitioner with further investigations? |

||||||||||||||

|

Procedural |

Patient with suspected giant cell arteritis who needs a temporal artery biopsy — how to organise this and who does it? Vascular surgeon, general surgeon, ophthalmic surgeon, rheumatologist? |

||||||||||||||

|

Ethical |

Morbidly obese patient with poorly controlled diabetes and severe interstitial lung disease who develops severe community‐acquired pneumonia with septic shock and acute respiratory failure — will mechanical ventilation be of benefit despite their wishes for full cardiopulmonary resuscitation? |

||||||||||||||

|

Male patient with newly acquired chlamydia urethritis after an overseas work trip asks you not to inform his wife who is also your patient — what is the appropriate course of action? |

|||||||||||||||

|

Contextual |

Patient who is a female refugee, speaks little English and has cultural sensitivities about being physically examined by a male doctor — how should the required clinical information be obtained? |

||||||||||||||

|

Patient who is new to the clinic and has several urgent and complex problems — how to prioritise to make best use of limited time? |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Assessing clinicians’ reactions to uncertainty using the Physician's Reactions to Uncertainty (PRU) scale*50

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Stress from uncertainty |

|||||||||||||||

|

Anxiety due to uncertainty (five items):

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Concern about bad outcomes (three items):

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Reluctance to disclose uncertainty |

|||||||||||||||

|

Reluctance to disclose uncertainty to patients (five items):

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Reluctance to disclose mistakes to colleagues (two items):

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Items are rated on a 6‐point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = moderately disagree; 3 = slightly disagree; 4 = slightly agree; 5 = moderately agree; 6 = strongly agree. The scale is scored by summing the responses to each item, noting some items are reverse‐scored. † Items that are reverse‐scored. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Strategies for clinicians in managing uncertainty64,65,66,67

|

Element |

Explanation |

Coping strategy |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Understand your own affective (or “gut”) reactions and level of tolerance to uncertainty |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Identify the type of uncertainty you are facing in a particular instance |

Determine if the uncertainty is primarily: |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Feel your way through a problem |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Let go of the need to know for sure |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Deprioritise uncertainties that are less relevant or consequential |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Anticipate and prepare for scenarios associated with uncertainty |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Identify and counter cognitive biases |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Exercise humility and acknowledge your limits |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Employ safety netting and follow‐up |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Share uncertainty with colleagues |

Discussing clinical conundrums with colleagues lends more confidence to your decisions and builds a group culture that accepts and embraces uncertainty |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Promote curiosity and flexibility over certainty |

Curiosity and an openness to new ideas and knowledge are a basic element of human cognition and a fundamental motivator of learning |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Share uncertainty with patients |

Admitting uncertainty will not lead to a loss of patient confidence if it is appropriately expressed (Box 5) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Communicating uncertainty to patients71,72,73,74

|

Aim |

Recommendation |

Example statements |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Preparing for the discussion of uncertainty |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Informing patients about uncertainty |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Helping patients deal with uncertainty |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Ian A Scott1

- Jenny A Doust2

- Gerben B Keijzers3

- Katharine A Wallis1

- 1 University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

- 2 Australian Women and Girls’ Health Research (AWaGHR) Centre, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

- 3 Gold Coast University Hospital, Gold Coast, QLD

Open access

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Gawande A. Complications: a surgeon's notes on an imperfect science. London, UK: Profile Books, 2008.

- 2. Kang SK, Berland LL, Mayo‐Smith WW, et al. Navigating uncertainty in the management of incidental findings. J Am Coll Radiol 2019; 16: 700‐708.

- 3. Haier J, Mayer M, Schaefers J, et al. A pyramid model to describe changing decision making under high uncertainty during the COVID‐19 pandemic. BMJ Global Health 2022; 7: e008854.

- 4. Stone L, Olsen A. Illness uncertainty and risk management for people with cancer. Aust J Gen Pract 2022; 51: 321‐326.

- 5. Farrell CM, Hayward BJ. Ethical dilemmas, moral distress, and the risk of moral injury: Experiences of residents and fellows during the COVID‐19 pandemic in the United States. Acad Med 2022; 97: S55‐S60.

- 6. Venus C, Jamrozik E. Evidence‐poor medicine: just how evidence‐based are Australian clinical practice guidelines? Intern Med J 2020; 50: 30‐37.

- 7. Kent DM, Paulus JK, van Klaveren D, et al. The Predictive Approaches to Treatment effect Heterogeneity (PATH) statement. Ann Intern Med 2020; 172: 35‐45.

- 8. Ramani D, Soh M, Merkebu J, et al. Examining the patterns of uncertainty across clinical reasoning tasks: effects of contextual factors on the clinical reasoning process. Diagnosis (Berl) 2020; 7: 299‐305.

- 9. Simpkin AL, Schwartzstein RM. Tolerating uncertainty — the next medical revolution? N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1713‐1715.

- 10. Lingard L, Garwood K, Schryer CF, Spafford MM. A certain art of uncertainty: case presentation and the development of professional identity. Soc Sci Med 2003; 56: 603‐616.

- 11. Alam R, Cheraghi‐Sohi S, Panagioti M, et al. Managing diagnostic uncertainty in primary care: a systematic critical review. BMC Fam Pract 2017; 18: 79.

- 12. Cooke GP, Doust JA, Steele MC, et al. A survey of resilience, burnout, and tolerance of uncertainty in Australian general practice registrars. BMC Med Educ 2013; 13: 2.

- 13. West CP, Tan AD, Habermann TM, et al. Association of resident fatigue and distress with perceived medical errors. JAMA 2009; 302: 1294‐1300.

- 14. Kuhn G, Goldberg R, Compton S. Tolerance for uncertainty, burnout, and satisfaction with the career of emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med 2009; 54: 106‐113.

- 15. Armstrong K. If you can't beat it, join it: uncertainty and trust in medicine. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168: 818‐819.

- 16. Englander R, Cameron T, Ballard AJ, et al. Toward a common taxonomy of competency domains for the health professions and competencies for physicians. Acad Med 2013; 88: 1088‐1094.

- 17. Kong G, Xu DL, Yang JB. Clinical decision support systems: a review on knowledge representation and inference under uncertainties. Int J Comp Intell Syst 2008; 1: 159‐167.

- 18. Sanders SL, Rathbone J, Bell KJL, et al. Systematic review of the effects of care provided with and without diagnostic clinical prediction rules. Diagn Progn Res 2017; 1: 13.

- 19. Lohse S. Mapping uncertainty in precision medicine: a systematic scoping review. J Eval Clin Pract 2022; 29: 554‐564.

- 20. Gordon GH, Joos SK, Byrne J. Physician expressions of uncertainty during patient encounters. Patient Educ Couns 2000; 40: 59‐65.

- 21. Heneghan C, Glasziou P, Thompson M, et al. Diagnostic strategies used in primary care. BMJ 2009; 338: b946.

- 22. Green SM, Martinez‐Rumayor A, Gregory SA, et al. Clinical uncertainty, diagnostic accuracy, and outcomes in emergency department patients presenting with dyspnea. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 741‐748.

- 23. Beresford EB. Uncertainty and the shaping of medical decisions. Hastings Cent Rep 1991; 21: 6‐11.

- 24. Greenhalgh T. Uncertainty and clinical method. In: Sommers LS, Launer J; editors. Clinical uncertainty in primary care: the challenge of collaborative engagement. New York: Springer Science and Business Media, 2013; pp. 23‐45.

- 25. Han PK, Klein WM, Arora NK. Varieties of uncertainty in health care: a conceptual taxonomy. Med Decis Making 2011; 31: 828‐838.

- 26. Pomare C, Churruca K, Ellis LA, et al. A revised model of uncertainty in complex healthcare settings: a scoping review. J Eval Clin Pract 2019; 25: 176‐182.

- 27. Hillen MA, Gutheil CM, Strout TD, et al. Tolerance of uncertainty: conceptual analysis, integrative model, and implications for healthcare. Soc Sci Med 2017; 180: 62‐75.

- 28. Lee C, Hall K, Anakin M, Pinnock R. Towards a new understanding of uncertainty in medical education. J Eval Clin Pract 2021; 27: 1194‐1204.

- 29. Helou MA, DiazGranados D, Ryan MS, Cyrus JW. Uncertainty in decision making in medicine: A scoping review and thematic analysis of conceptual models. Acad Med 2020; 95: 157‐165.

- 30. Hall KH. Reviewing intuitive decision‐making and uncertainty: the implications for medical education. Med Educ 2002; 36: 216‐224.

- 31. Wayne S, Dellmore D, Serna L, et al. The association between intolerance of ambiguity and decline in medical students’ attitudes toward the underserved. Acad Med 2011, 86: 877‐882.

- 32. Strout TD, Hillen M, Gutheil C, et al. Tolerance of uncertainty: a systematic review of health and healthcare‐related outcomes. Pat Educ Couns 2018; 101: 1518‐1537.

- 33. Brun C, Zerhouni O, Akinyemi A, et al. Impact of uncertainty intolerance on clinical reasoning: a scoping review of the 21st‐century literature. J Eval Clin Pract 20223; 29: 539‐553.

- 34. Korenstein D, Scherer LD, Foy A, et al. Clinician attitudes and beliefs associated with more aggressive diagnostic testing. Am J Med 2022; 135: e182‐e193.

- 35. Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Cook EF, et al. The association of physician attitudes about uncertainty and risk taking with resource use in a Medicare HMO. Med Decis Mak 1998; 18: 320‐329.

- 36. Bachman KH, Freeborn DK. HMO physicians’ use of referrals. Soc Sci Med 1999; 48: 547‐557.

- 37. Begin AS, Hidrue M, Lehrhoff S, et al. Factors associated with physician tolerance of uncertainty: an observational study. J Gen Intern Med 2022; 37: 1415‐1421.

- 38. Politi MC, Clark MA, Ombao H, Légaré F. The impact of physicians’ reactions to uncertainty on patients’ decision satisfaction. J Eval Clin Pract 2011; 17: 575‐578.

- 39. Hancock J, Mattick K. Tolerance of ambiguity and psychological well‐being in medical training: a systematic review. Med Educ 2020; 54: 125‐137.

- 40. Poluch M, Feingold‐Link J, Papanagnou D, et al. Intolerance of uncertainty and self‐compassion in medical students: Is there a relationship and why should we care? J Med Educ Curric Dev 2022; 9: 23821205221077063.

- 41. Kvale J, Berg L, Groff JY, Lange G. Factors associated with residents’ attitudes toward dying patients. Fam Med 1999; 31: 691‐696.

- 42. Sherrill WW. Tolerance of ambiguity among MD/MBA students: implications for management potential. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2001; 21: 117‐122.

- 43. Borracci RA, Ciambrone G, Arribalzaga EB. Tolerance for uncertainty, personality traits and specialty choice among medical students. J Surg Educ 2021; 78: 1885‐1895.

- 44. McCulloch P, Kaul A, Wagstaff GF, Wheatcroft J. Tolerance of uncertainty, extroversion, neuroticism and attitudes to randomized controlled trials among surgeons and physicians. Br J Surg 2005; 92: 1293‐1297.

- 45. Lawton R, Robinson O, Harrison R, et al. Are more experienced clinicians better able to tolerate uncertainty and manage risks? A vignette study of doctors in three NHS emergency departments in England. BMJ Qual Saf 2019; 28: 382‐388.

- 46. Pearson SD, Goldman L, Orav EJ, et al. Triage decisions for emergency department patients with chest pain: do physicians’ risk attitudes make the difference? J Gen Intern Med 1995; 10: 557‐564.

- 47. Mutter M, Kyle JR, Yecies E, et al. Use of chart‐stimulated recall to explore uncertainty in medical decision‐making among senior internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med 2022; 37: 3114‐3120.

- 48. Meyer AND, Giarina TD, Khanna A, et al. Pediatric clinician perspectives on communicating diagnostic uncertainty. Int J Qual Health Care 2019; 31: G107‐G112.

- 49. Tai‐Seale M, Stults C, Zhang W, Shumway M. Expressing uncertainty in clinical interactions between physicians and older patients: what matters? Pat Educ Couns 2012; 86: 322‐328.

- 50. Gerrity MS, White KP, deVellis RF, Dittus RS. Physicians’ reactions to uncertainty: refining the constructs and scales. Motiv Emot 1995; 19: 175‐191.

- 51. Cooke G, Tapley A, Holliday E, et al. Responses to clinical uncertainty in Australian general practice trainees: a cross‐sectional analysis. Med Educ 2017: 51: 1277‐1288.

- 52. Helmich E, Diachun L, Joseph R, et al. “Oh my God, I can't handle this!”: trainees’ emotional responses to complex situations. Med Educ 2018; 52: 206‐215.

- 53. Stephens GC, Rees CE, Lazarus MD. Exploring the impact of education on preclinical medical students’ tolerance of uncertainty: a qualitative longitudinal study. Adv Health Sci Educ 2021; 26: 53‐77.

- 54. Scott A, Sudlow M, Shaw E, Fisher J. Medical education, simulation and uncertainty. Clin Teach 2020; 17, 497‐502.

- 55. Patel P, Hancock J, Rogers M, Pollard SR. Improving uncertainty tolerance in medical students: a scoping review. Med Educ 2022; 56: 1163‐1173.

- 56. Sommers LS, Morgan L, Johnson L, Yatabe K. Practice inquiry: clinical uncertainty as a focus for small‐group learning and practice improvement. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22: 246‐252.

- 57. Graber ML, Rusz D, Jones ML, et al. The new diagnostic team. Diagnosis 2017; 4: 225‐238.

- 58. Hancock J, Roberts M, Monrouxe L, Mattick K. Medical student and junior doctors’ tolerance of ambiguity: development of a new scale. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2014; 20: 113‐130.

- 59. Schneider A, Wübken M, Linde K, Buhner M. Communicating and dealing with uncertainty in general practice: the association with neuroticism. PLoS One 2014; 9: e102780.

- 60. Geller G, Grbic D, Andolsek KM, et al. Tolerance for ambiguity among medical students: patterns of change during medical school and their implications for professional development. Acad Med 2021; 96: 1036‐1042.

- 61. Ndoja S, Chahine S, Saklofske DH, Lanting B. The erosion of ambiguity tolerance and sustainment of perfectionism in undergraduate medical training: results from multiple samplings of a single cohort. BMC Med Educ 2020; 20: 417.

- 62. Cristancho S, Lingard L, Forbes T, et al. Putting the puzzle together: the role of “problem definition” in complex clinical judgement. Med Educ 2017: 51: 207‐214.

- 63. Wasfy JH. Learning about clinical uncertainty. Acad Med 2006; 81: 1075.

- 64. Han PK, Strout TD, Gutheil C, et al. How physicians manage medical uncertainty: a qualitative study and conceptual taxonomy. Med Decis Making 2021; 41: 275‐291.

- 65. Ilgen JS, Eva KW, de Bruin A, et al. Comfort with uncertainty: reframing our conceptions of how clinicians navigate complex clinical situations. Adv Health Sci Educ 2019; 24: 797‐809.

- 66. Moffett J, Hammond J, Murphy P, Pawlikowska T. The ubiquity of uncertainty: a scoping review on how undergraduate health professions’ students engage with uncertainty. Adv Health Sci Educ 2021; 26: 913‐958.

- 67. Gheihman G, Johnson M, Simpkin AL. Twelve tips for thriving in the face of clinical uncertainty. Med Teach 2020; 42: 493‐499.

- 68. Meyer AN, Giardina TD, Khawaja L, Singh H. Patient and clinician experiences of uncertainty in the diagnostic process: current understanding and future directions. Patient Educ Couns 2021; 104: 2606‐2615.

- 69. Portnoy DB, Han PK, Ferrer RA, et al. Physicians’ attitudes about communicating and managing scientific uncertainty differ by perceived ambiguity aversion of their patients. Health Expect 2011; 16: 362‐372.

- 70. Han PK, Babrow A, Hillen MA, et al. Uncertainty in health care: towards a more systematic program of research. Patient Educ Couns 2019; 102: 1756‐1766.

- 71. Medendorp NM, Stiggelbout AM, Aalfs CM, et al. A scoping review of practice recommendations for clinicians’ communication of uncertainty. Health Expect 2021; 24: 1025‐1043.

- 72. Simpkin AL, Armstrong KA. Communicating uncertainty: a narrative review and framework for future research. J Gen Intern Med 2019; 34: 2586‐2591.

- 73. Kalke K, Studd H, Scherr CL. The communication of uncertainty in health: a scoping review. Patient Educ Couns 2021; 104: 1945‐1961.

- 74. Dahm MR, Cattanach W, Williams M, et al. Communication of diagnostic uncertainty in primary care and its impact on patient experience: an integrative systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2023; 38: 738‐754.

- 75. Bean RB, Bean WB. Sir William Osler: aphorisms from his bedside teachings and writings. New York: Henry Schuman, 1950.

Summary